This is one in a series of essays on important works of Korean cinema available free to watch on the Korean Film Archive’s Youtube channel. Previous selections include Aimless Bullet, Iodo, 301, 302, The March of Fools, Seopyeonje, Wangshimni, My Hometown, Madame Freedom, Chil-su and Man-su, and Night Journey. You can watch Deep Blue Night here.

Speeding through the desert in a convertible, blasting “Highway Star” on the radio: as much appeal as that fantasy has held for Americans, it’s held even more for non-Americans. Such a scene opens Deep Blue Night (깊고 푸른 밤), a Korean film shot entirely in the United States and intensely, even grimly concerned with the broader notion of the “American dream.” At the wheel of the car — incongruously, not an American classic like a Mustang or a Corvette, but a Mercedes — is a Korean man of about 30. In the passenger’s seat is a girl, another essential element of the fantasy, but before long the man will have abandoned her in Death Valley, having roughed her up, relieved her of an envelope full of cash and, deaf to her entreaties, continued on his way. What looked like a simple living of the dream turns out to be part of a mission before which morality is clearly no object.

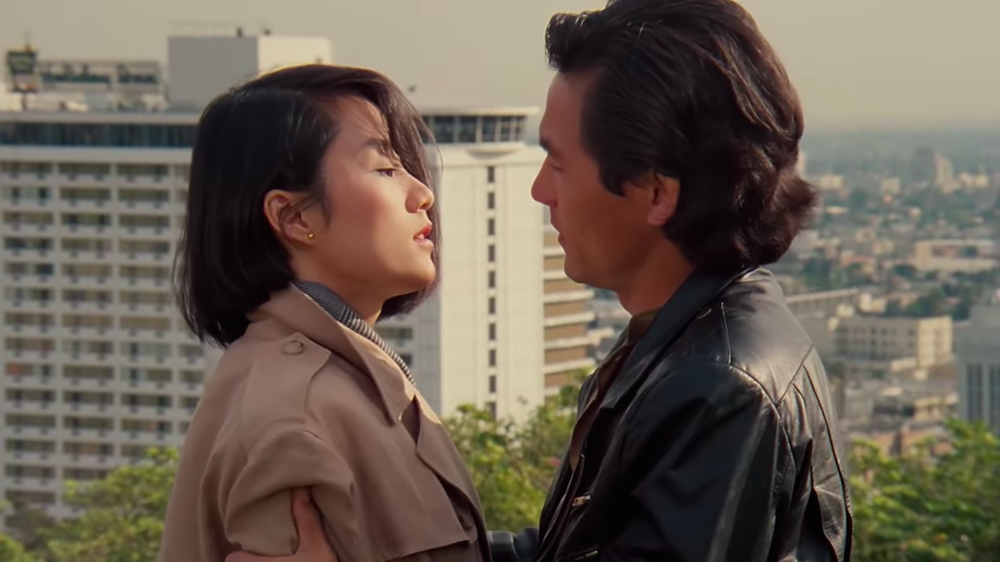

The man’s name is Baek Ho-bin, and Los Angeles is the destination of a months-long journey that began in his homeland. From there he first made his way to Mexico, then crossed the border into San Diego, where he met the young lady, a fellow Korean, whom he left in the desert. In Los Angeles he connects with another Korean woman, a bartender who introduces herself only as “Jane.” An American citizen, Jane runs a side business entering into sham green-card marriages in exchange for money, just the service for a man like Ho-bin eager to bring his wife and unborn child over from Korea. In time she lets Ho-bin live in her hillside house, and even sets him up with a job at a convenience store. That the cynical operator eventually develops genuine feelings for the handsome rogue may at first seem like a cliché straight out of a romantic comedy with Julia Roberts and Richard Gere — whom Ahn Sung-ki, a child star in the 1950s and now an icon of Korean cinema, resembles in the role of Ho-bin.

Ahn looks and acts most like Gere as he appears in a movie that certainly doesn’t count as romantic comedy, but does count among the underrated Los Angeles movies of the 1980s: Jim McBride’s American remake of Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless, which is more respectable than it sounds. Whereas most American versions of foreign films lighten up the originals, McBride’s Breathless darkens Godard’s debut down, replacing its doomed romantic flair with a nihilistic seediness befitting the change of setting. It also swaps the nationalities of the main characters: Jean Seberg’s Patricia becomes Valérie Kaprisky’s French UCLA student Monica, and Jean-Pierre Belmondo’s Michel becomes Gere’s murderous drifter Jesse. Each in his own way, both Jesse and Ho-bin are archetypes of the aggressive young man in America, the former native-born and full of aimless vitality, the latter a new arrival on the make. Neither show any compunction when dealing — sexually, violently, or both — with those in the way.

Ho-bin moves on Jane first, attempting to take her to bed the very night of their quickie wedding in Las Vegas, but declines to push his advances further when she puts a gun to his head. Though he physically reciprocates when she makes advances of her own later, after warming up to him, he remains explicit about his dedication to the initial plan: stay married long enough for US citizenship, then get divorced and send for his real wife. Wise to Jane’s scheme, having taken notice of her six marriages by age 28, a couple of immigration officers (looking pulled from a 1940s character-actor casting office) show up at her home to conduct an interrogation. Ho-bin — who by this point has enthusiastically abased himself with a Hollywood-inspired “American” name, “Gregory Baek” — delivers a rehearsed speech in praise of the land that employs them: “I love America, you know? America is the greatest country in the world. America is the country of liberty, freedom, and opportunity. That’s why I want to live here.”

Ho-bin’s words, or the impromptu rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” with which he follows them, wins the officers over. And indeed, he soon seems well on his way to realizing his American dream: having passed his citizenship test at Los Angeles City Hall, he drives in his latest convertible (now a red MGB) straight to the nearest pay phone to tell his wife in Korea the good news. He can live in America as long as he wants. He’ll work like a dog and buy the most expensive car and the most expensive house, one on a hill with an ocean view. There’ll be a chauffeur and servants. If she comes right away, the baby will be born an American citizen, maybe even grow up to become a baseball player. The camera revolves in circles around Ho-bin during his entire exultation, one of the signature moves of director Bae Chang-Ho. Though known as “the Steven Spielberg of Korea” (at least before the rise of Okja and Parasite director Bong Joon-ho), Bae has spoken of his intent in Deep Blue Night not to create a fantasy but to deflate one, specifically the fantasy of an idealized America so fervently believed in by his countrymen since the Korean War.

Bae’s source material is the work of Choi In-ho, a celebrated novelist and critic of South Korean modernity. Though based more on a novel called Desert Above Water (물 위의 사막), Deep Blue Night shares its title with another of Choi’s best-known works, a short story that won the prestigious Yi Sang Literary Award in 1982. Though they have no specific characters or events in common, the film and the story both deal with Koreans in California. In the latter, two men in their thirties drive to Los Angeles from San Francisco, where they’d spent a destructive bacchanalia of a night at the house of Korean acquaintances. The older of the two, never referred to by name, seems to be a successful man of letters back in Korea; the younger, Jun-ho, was once a somewhat famous musician. “He’d left Korea to travel, as had Jun-ho, but their objectives differed,” writes Choi (in an English translation by Bruce and Ju-chan Fulton). “Jun-ho had decided that traveling here presented an opportunity, that he should seize that opportunity and sink roots.”

Jun-ho’s idea of sinking roots in America amounts to driving around in a second-hand beater, remaining in both perpetual motion and a perpetual cannabis-induced fog. “Jun-ho had an unlucky past,” Choi writes of the character’s life in Korea. “At the height of his popularity he’d been barred from the stage for the ‘crime’ of smoking marijuana. In the four years since, he’d tried his hand at one thing or another and managed to accumulate a fair amount of money, but eventually had squandered in all away.” A self-styled intellectual on “an island of wretched, foolish aboriginal people” where “the knowledge at his command was made illegal by the authorities,” the writer is thwarted even more severely by his own anger: “He’d been angered by the novel he was serializing in the newspaper, angered by every story or novel he’d written. He was angered by the sight of his sentences in print, by the sight of the newspaper that carried them. The screws of self-restraint that might have checked that anger loosened, and he was powerless before the rage that gushed out.”

Try as he might, the writer can’t identify the source of this rage: “What was it that made him so angry? And what was it that made Jun-ho fearful, that made him take up marijuana again? What could have made him abandon his family and become an illegal alien?” Jun-ho’s smoking habits give him access to the sublimity of the American landscape, or so he claims, but the writer experiences only a void of sensation. He feels “no emotion — not at the Beverly Hills mansions, not at the elaborate cartoon characters at Disneyland, or the Haunted Mansion, not at the barren expanse of Death Valley, at after-dark Las Vegas, the city of never-night, or at the snow-draped Yosemite landscape.” He sums up his reaction to all he sees on the road with just one word: “big.” Both the work of Choi’s that gives Deep Blue Night its basis and the film itself return to the image of the desert, a representation of what, to all these Korean characters, the promised land of America has unexpectedly become.

In Deep Blue Night, American life has turned Jane into not just an impulsive gun-puller but an alcoholic as well. “Do you know where we are?” she asks Ho-bin a few drinks into one evening. “Los Angeles,” he answers, “the city of angels.” No, she says, “this is a desert” — a common climatic misconception about Los Angeles, but never mind. She then tells of her first husband Michael, a black American G.I. stationed in Korea. “I wanted to come to the States. I thought we’d have parties every night and dance in a mansion by the sea, just like in a movie,” a fantasy sharply repudiated by the small, dusty Texas town to which Michael first brought her. And at night “he would get drunk and beat me up to get rid of his hangups about being black,” weeping while striking her. After fleeing the marriage she found herself made to surrender custody of their young daughter by the court. “I hit Laura a couple of times when she was smaller,” she admits to Ho-bin. “Don’t we do that in Korea? When a child doesn’t behave her mother gives her hell, and the kid has to apologize, right?”

Laura nevertheless stays with Jane from time to time, and Ho-bin’s friendliness with the girl seems to determine Jane to keep him as a real husband. To this end she lies about having become pregnant, and Ho-bin in turn lies about his wife back in Korea having died in childbirth. In yet another layer of deception, Jane intercepts one of the packages Ho-bin’s real wife sends to the downtown flophouse where he’d stayed after arriving in the city. In it she finds a cassette tape on which his wife has recorded a confession: tired of waiting for her husband to return, she’s gone in for a late-stage abortion and taken up with another man. And so the film that began with Ho-bin speeding through the desert toward Los Angeles with the girl he picked up in San Diego ends with him speeding with Jane through the desert toward San Francisco — the film has an imperfect grasp of California geography — on the way making an even more fateful stop in Death Valley, a location quite possibly chosen for the foreshadowing power of its name.

Korean critics have compared the ending of Deep Blue Night to that of Roman Polanski’s Chinatown, another film with a bleak view of Los Angeles, and by extension of America. Certainly Baek Ho-bin’s pursuit of the American dream is as futile, and as fated to end in violence, as Jake Gittes’s investigation of the Department of Water and Power. Ho-bin leaves the film as he entered it, as an embodiment of the untempered immigrant id, seeking only to remain in America making as much money as possible by any means necessary. He passes off his unimaginative infatuation with Hollywood imagery and desire for self-enrichment — the house with an ocean view, the fancy chauffeured car — as a virtuously patriotic love of his new homeland, projecting a readiness to repudiate the old country entirely. (Though an extreme example of this, Ho-bin is hardly alone in Korean cinema. A comparison with, say, Japanese characters in America is illuminating: take the young Yokohama couple in Jim Jarmusch’s Mystery Train who, tourists rather than immigrants, come expressly to make a near-religious pilgrimage to Sun Studios.)

Choi’s “Deep Blue Night” ends not in Death Valley but along California State Route 246, the result of a midnight wrong turn off the Pacific Coast Highway. There the car finally breaks down, a failure in the face of which the writer begins to find his equanimity. “Los Angeles is a fictitious place name; it doesn’t exist in this world,” Choi writes. “They’ve been speeding thousands of miles toward this fictitious city. But no matter. No need to try to diving what’s there at the end of Route One.” Taking a first, giant toke from Jun-ho’s stash, the writer comprehends the extent of his defeat: “His entire life, all he had ever seen and heard, the honor and empty fame he had possessed and wasted, the law and justice he had believed to be right, the ambitions sometimes realized and sometimes betrayed, the pleasures and sexual appetite he had pursued without end, the plentiful supply of women he had possessed for a time and discarded, all these things that had beaten him mercilessly had finally and awfully conquered him.” Only there, at the end of the new world, “when he realized he had been conquered, his rage was truly reduced to ashes.”

Related Korea Blog posts:

Western Avenue: How Korean Cinema Portrayed the 1992 Los Angeles Riots

Looking Back at LA Arirang, the 1990s Korean Sitcom about Life in Los Angeles

The Unbearable Preposterousness of Westernization: Park Kwang-su’s Chil-su and Man-su

A Korean Travel Writer Reveals the Los Angeles Even Angelenos Don’t Know

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.