I write these words on the KTX, South Korea’s high-speed train. Though not as iconic as Japan’s Shinkansen, it certainly does the job more efficiently, and for the passenger more comfortably, than any rail service I remember back in the United States. Even those who’ve never been to Korea may be familiar with the look and feel of the KTX experience, especially if they happen to like zombie movies. The standard for Korea’s cinema of the living dead was set in 2016 by Yeon Sang-ho’s Train to Busan (부산행), that train being a KTX on a run from Seoul to the country’s second-largest city, at the other end of the country on its southeastern coast. Faithful to its setting right down to the employee uniforms and seat-pocket travel magazines, the film no doubt pleased train aficionados as much as it did zombie aficionados, and not just Korean ones either.

Train to Busan‘s impact is evidenced by the academic essay collection Rediscovering Korean Cinema, in which the film appears not just as the subject of a chapter but the source of its cover photo. In his consideration of “South Korea’s first zombie blockbuster,” University College London’s Keith B. Wagner describes the film, with its “family-rescue-drama-cum-zombie-survivalist-contamination-anti-neoliberal” sensibilities, as “a polished apocalyptic tale that is unafraid to touch on pressing social issues that matter to Koreans.” This is in keeping with the genre’s capacity as a vehicle for social critique, established at least since 1978 when George Romero’s Dawn of the Dead showed us zombies shambling, with a somehow recognizable mindlessness, through a shopping mall. Jim Jarmusch (who happens to have gathered a robust Korean fan base) took the satire further in last year’s The Dead Don’t Die, whose 21st-century zombies moan for coffee, wi-fi, and Xanax.

The more traditional, wholly non-verbal zombies of Train to Busan have no desires apart from the usual one for human flesh. In this and most other respects they adhere to the standard zombie behavioral model, staggering unthinkingly toward any living being in the vicinity in order to bite it and thus turn it undead as well. As with every entry in the genre, the film has its own take on what Wagner calls “an aesthetics of the undead with the zombie characters displaying whitened irises, veiny and blanched faces covered in mucus, flesh particles and blackened blood spatter, and bodies hunched over and in various stages of decay and decrepitude.” There’s something distinctive in the way Train to Busan‘s zombies move, like contortionists wired up with electrodes placed and firing and random, but to the film’s international audience, one characteristic in particular will stand out: they’re all Korean.

Wagner frames this decision as “monoracially motivated to firmly establish this as a Korean-only zombie film.” In most Korean movies, of course, an all-Korean cast is hardly notable, nor at odds with the reality of daily life here. (Token Westerners do appear on screen now and again these days, though I can’t say I miss them when they don’t.) But in a more recently imported Western genre like zombie horror, if I follow Wagner’s reasoning, the absence of a single non-Korean face — living, dead, or undead — underscores an active Koreanization of the overall form. So does the social critique it mounts on the speeding and increasingly zombie-infested KTX train: an indictment of “failed crisis management, pathogenic spread of disease, and upper-class entitlement,” among other “deleterious elements of neoliberalism coming to affect modern Korean life.” And failed crisis management would have been on every domestic viewer’s mind when Train to Busan came out in the summer of 2016.

Just over two years earlier, 305 died in the sinking of the M.V. Sewol, including 250 high-school students on a class trip. The national anger and resentment at the seemingly incompetent response of the now-jailed President Park Geun-hye has taken cinematic forms like the documentary Bad Country and the feature Birthday, and Train to Busan arguably has a point to make about it as well. Where an American zombie film might play on racial differences among its main characters while revealing society in extremis, Train to Busan uses a class hierarchy, placing under siege a fund manager, a blue-collar bruiser and his pregnant wife, a teenage baseball team, and elderly sisters who remember harder times. Below them is a homeless man and above is a middle-aged corporate CEO, whom Wagner views as “the embodiment of an inept, indifferent, vain, and scapegoating government under Park Geun-hye.”

Making their way through the train, some of its cars filled with zombies and others relatively safe, these characters find themselves thrown together in unpredictable combinations throughout the film. This in contrast to Bong Joon-ho’s brazenly unsubtle Snowpiercer from 2013, whose train endlessly circling an uninhabitable Earth linearly arranges what’s left of society: the poorest at the back, the richest up front, and everyone else ordered in the cars between. On the way to becoming the most famous Korean filmmaker alive, a destiny fulfilled this year when Parasite swept the Academy Awards, Bong also made a stop in the monster-disaster field with 2006’s The Host. That film’s opening scene shows an American military official ordering a Korean subordinate to dispose of a great deal of formaldehyde straight into the Han River; later, out of the very same waterway emerges an amphibian colossus bent on running amok in Seoul.

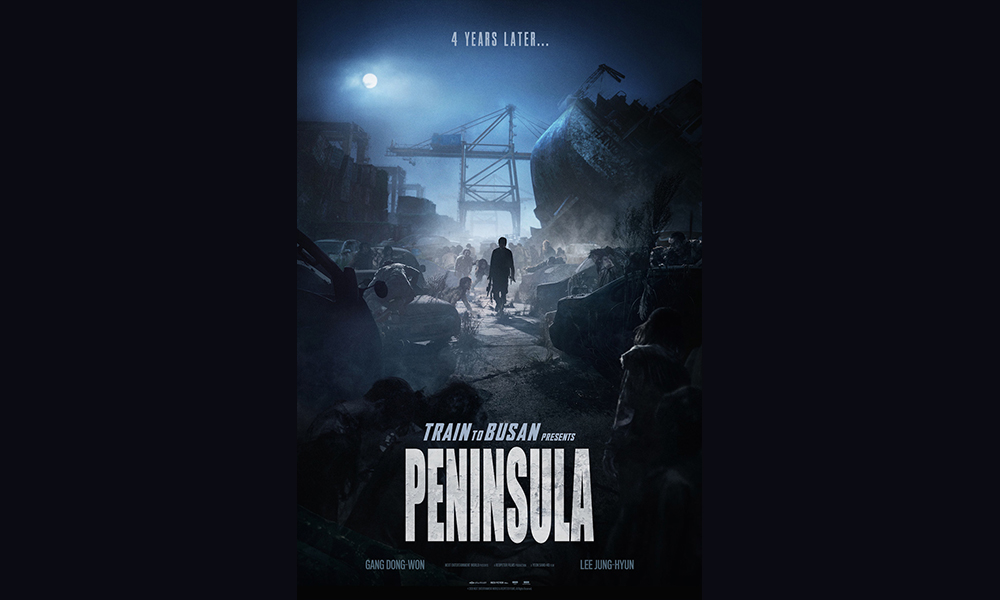

A decade on, Train to Busan lays the blame for its zombie contagion at Korea’s own door — specifically, the door of a poorly overseen Korean biotechnology lab. (In The Dead Don’t Die the inciting activity is something called “polar fracking,” which carries a similarly implicit charge of hubris against the United States.) And “if Train to Busan’s KTX train cars incubate a Korean-made pandemic, contained in just one zone of the larger outbreak,” writes Wagner, “this moving petri dish proves the impossibility of maintaining national boundaries in the era of globalization.” That impossibility surely won’t be far from the thoughts of viewers, no matter their nationality, who revisit the film in 2020, the year the global coronavirus pandemic. Nor will it be far from those of the audience for Peninsula (반도), Yeon’s follow-up to Train to Busan that just last month opened here in Korea.

Peninsula is not a straightforward sequel, as the director has publicly stressed, but a standalone story that takes place after the events of the first film. In that sense it constitutes a bookend along with Seoul Station, the animated prequel (Yeon having been an animator before expanding into live action) that came out a month after Train to Busan. Both movies adhere to zombie horror’s evident mandate that the cast of characters be winnowed as severely as possible by the end: Seoul Station left none of its principals alive, and Train to Busan just two, a woman and a young girl, neither of whom appear in the new film. Its main action set four years later, Peninsula presents us instead with a Marine Captain named Jung-seok and his brother-in-law Chul-min, two of the relatively few Koreans who manage to catch a boat out of the country before it becomes completely overrun by zombies.

The boat itself also falls victim to a zombie outbreak, which claims Chul-min’s wife — Jung-seok’s sister — and their young son. Later, living stateless and tormented by their memories in Hong Kong, the two men are offered a chance at a new life by a classic crime kingpin of a Westerner: go back to Seoul, retrieve an abandoned truck containing $20m USD, and they’ll each get a share of the fortune. As soon as Jung-seok, Chul-min, and their clearly expendable Korean collaborators arrive in their wrecked, depopulated homeland, Peninsula stops playing like a zombie movie and starts playing like whatever post-apocalyptic neo-Western-type genre John Carpenter’s Escape from New York belongs to. And even that film had zombies, of a kind, in the form of the “crazies” who ascend from the sewers and swarm the streets of the walled-off Manhattan Island by night.

In Peninsula, however, night affords a certain degree of protection from the zombies. They can’t see in the dark, as those who remember Train to Busan will know, and so default to stagger-running in the direction of the nearest loud noise. In the new film, Yeon gets considerable mileage out of this condition — zombie horror being a form that stands or falls on the observance of its own rules — and exaggerates to mothlike proportions his zombies’ previously suggested attraction to points of light. Thus controllable by anything that booms or glows, the undead become a weapon in themselves, distracted and redirected this way and that by the film’s heroes and villains. This time, the struggle for the former is against not just the zombies but also the rogue militiamen-turned-warlords who run a savage makeshift society in the ruins of Seoul.

An abundance of homicidal motorists dressed in filthy rags has earned Peninsula comparisons to the later Mad Max movies. This is also aptly evokes the sequel’s greater detachment from reality than the original. Train to Busan works so well because of the mundane realism of all its non-zombie elements: the train even makes the stops in the less-distinguished cities of Daejeon and Daegu it would in real life, and the film stages action set pieces tailored to the layout of each station. Peninsula‘s devastated Seoul of looks recognizable enough, but most of its scenes could play just as well in any emptied-out cinematic urban space. It all functions primarily as a stage for car chases and the annihilation of wave after wave of zombies, much like the perfunctory backdrops of the repetitive cellphone games, often seen played on the Seoul Metro, based on mowing down hordes of orcs, soldiers, and space aliens.

Jung-seok gets rescued from one such horde early on, by a teenage girl driving an SUV — and not just driving but keeping pedal firmly pressed to metal, executing turn after precision handbrake turn calculated to collide with and splatter as many of the living dead as possible. The calculation is on the part of the filmmakers, realized with the assistance of no minor labor on the part of their visual effects professionals. Both more elaborate and duller than anything in Train to Busan, this sequence has an odd weightlessness, like a non-playable video game. But it is the petite avenger herself who deals the fatal blow to the film’s sense of reality. As often as the character type of the Ass-Kicking Young Girl has lately appeared in Western action films, it has yet to be plausibly pulled off. Much like the Aggressively Foulmouthed Grandma of lowbrow comedy, it’s too pure a fiction to carry any weight.

As it unfolds, Peninsula reveals itself to be in essence a cartoon, much more so than Yeon’s actual animated films, all of them unrelievedly grim. Those include Seoul Station, set entirely in and around the titular transit hub, an area notorious for its visible homeless population (which still doesn’t exceed that of the average American downtown). When the Korean zombie outbreak begins, it spreads first through the lowest tier of society; the story’s runaway-hooker protagonist is one of its better-off characters. Though saturated with a greater amount of violence, much of it grotesque, Peninsula is by far the lighter picture: the corpse-decorated militia compound, for instance, is a former shopping mall, and its logos for American chains like Krispy Kreme and T.G.I. Friday’s remain visible in the background of Coliseum-style death matches between prisoners and captive zombies.

Like most Korean disaster movies, Train to Busan included, Peninsula is also not without historical resonances. Whereas the earlier film drew almost too obvious an allegory with the time of the Korean War, when Busan was the only stronghold against the invading Northern army, the new one returns South Koreans to the status of refugees without a country to call their own. But international audiences will key more readily in to the theme of a country’s total devastation by, in effect, infectious disease, from whose new relevance the film will surely benefit. The question, given the now-perilous state of the movie-theater industry across so much of the world, whether and how they’ll come out to see it. It has, in any case, performed well so far in Korea, ironically one of the countries whose day-to-day life has been least disrupted by COVID-19.

#Alive tells the story of two people struggling to survive as a mysterious illness spreads throughout Seoul. Photo: Spackman Entertainment Group

Not that Korean moviegoing has been entirely unaffected. The multiplexes of Seoul were fairly quiet between February, the month of the country’s first major outbreak, and June, toward the end of which the first major Korean film of the coronavirus era dared to open. Also, as it happens, a work of zombie horror, Cho Il-Hyung’s #Alive (#살아있다) is in a sense even more relevant to the current moment than the whole Train to Busan trilogy. Adapted from a screenplay by American filmmaker Matt Naylor, the entire film takes place in a Korean-style complex of apartment towers. Its first act is confined to the home of Joon-woo, a twentysomething computer-game streamer thrust into isolation when he wakes up to learn that a zombie contagion is sweeping through the country around him.

Joon-woo eventually joins forces in the fight for survival with another survivor in the complex, a girl in the building on the other side of the ever more undead-filled parking lot. This doesn’t happen, however, until his power, water, and food and especially internet are gone. In much of the world subject to coronavirus lockdowns, the internet has constituted an invaluable lifeline to the outside world. It has also, at least in countries served by Netflix, spread enthusiasm for Korean visions of the zombie apocalypse. The chief vector has been Kingdom, an ambitious series produced by Netflix itself that brings zombies into not just Korea but early 17th-century Korea. That period has been very often treated by more traditional period dramas, but to their political and social intrigue Kingdom adds the fresh ingredient of a zombifying plague.

Like #Alive and Peninsula, Kingdom — whose second season debuted at the height of Korea’s COVID troubles in March — has benefited by being inadvertently, and somewhat eerily, well-suited to our times. One one level, these are all simply Koreanizations of Western forms: 28 Days Later on the KTX, The Walking Dead in the Joseon dynasty. But on another, the local preoccupations dramatized in 21st-century Korean disaster, monster, and zombie spectacles have turned out to be rather less local than their creators might have imagined. Wagner takes the likes of Train to Busan as an example of “glocalization,” a concept that “encapsulates a phenomenon where inbound and outbound processes of cultural hybridity come to affect all societies, their citizens, and their mediascapes.” For my part, I just hope the now vividly imaginable potential for zombie attacks doesn’t become yet one more excuse for America not to build high-speed trains.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Reading Albert Camus’s The Plague in the Time of the Coronavirus

America Has School Shootings, Korea Has Sinking Ships

Birthday, the First Tearjerker About the Ferry Disaster that Killed 250 High-School Students

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.