The British Pre-Raphaelites, founded as a painterly reform movement in the middle of the 19th century, are notoriously easy to dunk on. Frequently criticized as purveyors of stilted Romantic freeze frames (in their figural works) and of a monomaniacal realism (in their nature-focused images) that in the very same century would be eclipsed by the invention of photography, they’ve become a shorthand for good intentions gone awry, and a reminder that dramatic spirit-affirming theories, if left unchecked, can easily devolve into camp.

Their American counterparts, brought to light by an exhibit at the National Gallery of Art, aren’t exactly immune to these accusations. The American Pre-Raphaelites: Radical Realists, on view until July 21, is stuffed to the brim with eye-achingly bright flowers and more still-lifes of dead birds than even the biggest dead-bird-fan could possibly find palatable. The gallery walls are spangled with, among other minor atrocities, close-up studies of bird nests propped on the forest floor that would have small town grandmas everywhere watering at the mouth, and baubly depictions of grapes that seem like they’d be more comfortable adorning the walls of an off-ramp Olive Garden than those of a museum.

But despite these quibbles — which, admittedly, are fun in their own way — the exhibit offers up remarkable moments of beauty, while its clear curation effortlessly unearths a forgotten history of influence. The show pegs the rise of the American Pre-Raphaelite movement to a tour John Ruskin made of America in the middle of the 19th century. Ruskin’s insistence on en plein air drafting, strict, workmanlike methods, and the patchwork analysis of light became touchstones for the American painters, ultimately giving their movement a strangely different spirit than its English counterpart, one that largely eschewed figural canvases and instead dwelt on the land.

Supporting this shift was a lesser-known influence, that of Thomas Cole, the enigmatic draughtsman of cataclysmic natural visions who, in a pioneery stiffening of Ruskin’s original recommendation, insisted on tramping through fields and over rough mountain paths — cutting right through the difficult landscape — to find his views. Renowned amongst the American Pre-Raphaelites for his metaphysical landscapes, Cole was already gone by the time the American movement started (strangely enough, he died in 1848, the year of the British movement’s founding), but his home in the Hudson Valley became a shrine of sorts for the Americans. Thomas Charles Farrer’s A Buckwheat Field on Thomas Cole’s Farm, for example, was painted from the forebear’s property.

The painting that kicked it all off, Ruskin’s own Fragment of the Alps, goes a long way towards explaining the intermingling of spirituality and scientific exactitude found in the best of the American Pre-Raphaelites’ works. Shuttled around America in a touring exhibition in the year 1857, the small canvas is a fantasia of vivid yellows and saturated purples, yet this almost surreal medley stems from no more mystical source than Ruskin’s hidebound attention to the play of light on stone. As the exhibition notes make clear, the careful delineation of the natural environment was a profoundly moral act for Ruskin. Detail became a form of prayer, a sort of thanksgiving for and hymn to God’s creation. The delicate plexing of boughs in Charles Herbert Moore’s Pine Tree, from 1868, are a perfect non-Ruskinian example of this drive — the detail is so fine that the tree seems to be melting upward, the fine pen markings gradually being blown away by the wind.

Between the exhibit’s broad vistas and minutely realized ephemera, it manages to capture American painters torn between the grand and the picayune as ways of expressing the bountiful landscape of their home. Moore, as it turns out, was a luminary of little things. His Lilies of the Valley, a watercolor from 1861, is less than a foot tall, offering up a fairy’s-eye-view of the blue drooping blooms in which the filigree of the flowers’ stems assumes a strange solidity, as of wrought iron. Moore, who lectured on Ruskin’s theories at Harvard, was a fan of the isolated close-up — his Dried White Oak Leaf depicts a frilled arabesque of dull gold, spotlit in white, as though a divine eye had singled it out for attention.

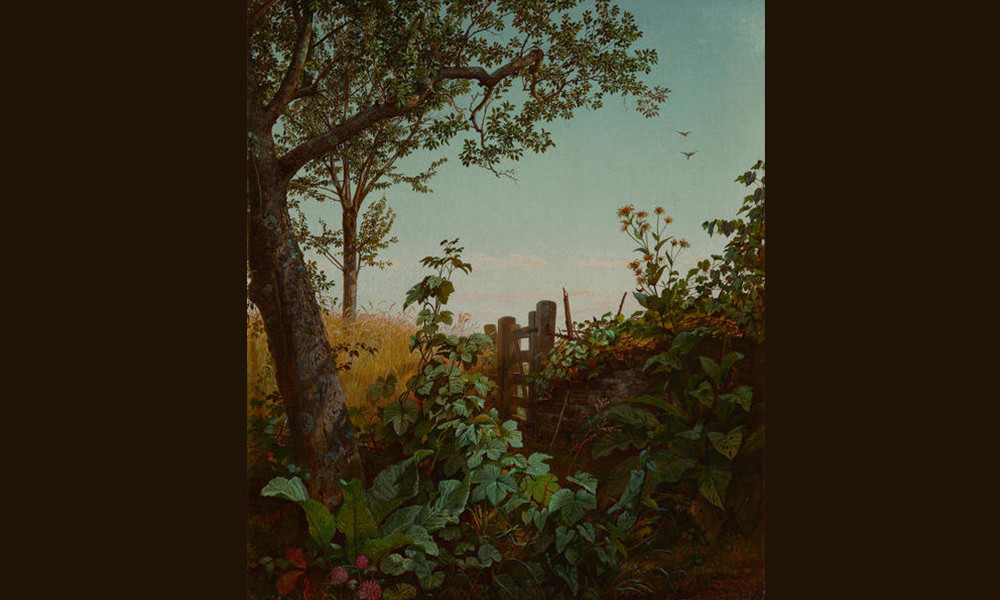

While grander vistas in the exhibit, bled dry by a sense of unalloyed awe, come off as static, empty byproducts of the surveyor’s art, it’s in middling subjects — closed-off fields and family homesteads — that the American Pre-Raphaelites found firmer footing, deftly suturing their spiritual inclinations to these cozier scenes. John William Hill’s West Nyack, New York (The Lilies of the Field), whose title references the Sermon on the Mount, captures the ancestral Hill home in the background, while the foreground is dominated by the titular lilies. Painted in 1865, William Trost Richards’ A Neglected Corner of the Wheatfield — probably the most iconic work in the exhibit — presents a picturesque facade, with unruly weeds impinging on a regulated wheatfield and a lightly decrepit post-and-rail fence stamped in the picture’s center. But behind the painting’s simple bucolicism lies a coded message; as the exhibition notes explain, “the Union cause was often symbolized in the popular press by wheat,” as opposed to the South’s cotton.

The looming tragedy of the Civil War haunts the exhibit, with Thomas Charles Farrer’s exuberantly titled Gone! Gone! depicting a young woman grieving the loss of a loved one. Farrer drew the essence of his painting from Romantic works by the British Pre-Raphaelite John Everett Millais, but there’s something in the work that hearkens back to even older forms. The simplicity of the woman’s pose seems somehow Gothic, and the brightness of the window scene behind her — a view at dusk of the Hudson River — feels torn from the Quattrocento. While figural compositions like Farrer’s were central to the British mission, the Americans by and large managed to transfer the moralizing themes of the British movement away from figures and onto the landscape. Farrer, who’d studied with Dante Gabriel Rossetti, was one of the biggest American proponents of figural works, but his pictures, typically indoor scenes, lack the breathlessness and flow of line you’d expect to find in a work by his teacher — his lines are crisp, his poses stiff, with a sort of religious intensity turning the figures to stony archetypes of suffering.

Other figural works in the exhibit show a strange interest in material coziness that often overpowers their more British-derived affects. William John Hennessy’s Mon Brave is a somber depiction of a young woman kissing the image of her lost lover, but while the girl’s flowing hair is a clear signal of British Pre-Raphaelite influence, the eye is drawn instead to the memorial wreath that bears the painting’s title. Its severe detail — ruffled and bristling with petals — stands in clear contrast to the hazy facture of the wallpaper, which seems to feather away into a blurry mist. The immateriality and morbidezza cribbed from the British scene — the ghostly wallpaper, the flowing, ungraspable hair — here meet a profoundly American passion for objects and density of detail.

The exhibit has your standard grab-bag of scènes à faire — plenty of shrubbery and boscage to go around — but it also features several strange one-offs, works that gesture dimly at other movements still to come. The frilly umbrellas of the two trees in Henry Roderick Newman’s Study of Elms, for example, seem a fore-echo of impressionism, one that resounds whenever the stippling technique employed by many of the painters falls on subjects full of fine filiations — an ancient elm hung with vines, for instance, or the grass on a windy hillside. Milkweeds, a watercolor by Fidelia Bridges, one of the more well-known woman artists working in the Pre-Raphaelite idiom, presents an almost hallucinatory wash of colors, redolent of the shattered, demented skies of Edvard Munch. Henry Farrer’s Winter Scene in Moonlight, from 1869, is a stark nocturnal moonscape, flensed and oddly regimented, that seems like the setting for a Beckett play.

It’s no wonder that seemingly sui generis works like these should be among the best in the collection. The American Pre-Raphaelites were, after all, a movement held together by principle yet fractured by the immensity of its subject. If Cole’s ideal of a rough engagement with the landscape never seems to have fully inserted itself into the movement, it’s because the strong pull of the wilderness was offset by another equally tempting drive. It’s hard to view Farrer’s occasional homely sketches of lamp-lit reading sessions and young women drawing outdoors while wrapped in firm-looking quilts without finding, secretly expressed, the old fear of woods and wolves, of dark nights and winters that gnaw to the bone.

The final room in the exhibit is given over to the works of Henry Roderick Newman, granted the sobriquet of “The Last Ruskinian” by the gallery notes. Based in Florence in the latter half of the 19th century, Newman made excursions to countries like Egypt and Japan, developing a lush style curiously intent on patterns. His watercolor from 1898, Sasanqua, Wild Tea, Yokohama, for example, sets a goblet of minutely realized camellias before a citrous background reminiscent of the textile designs of William Morris. As the last of his line, Newman presents a satisfying summation of the American Pre-Raphaelites’ modus operandi, one in which the world, subjected to a scientific gaze, is made to disclose a surfeit of detail, turning nature into ornament and enshrouding its mad volubility in a peaceful, palatably domestic guise.

Image: Neglected Corner of the Wheat Field (1865), William Trost Richards