In her landmark book, This Sex Which Is Not One, Luce Irigaray begins with the story of a man breaking into a locked house. This anecdote, rich in its theoretical underpinnings, foregrounds the work’s concerns with questions of power, intimacy, and the psyche. For Irigaray, these dimly lit rooms, in all of their strangeness and idiosyncrasy, stand in for the space of the imagination. The story, then, becomes one of psychological violence, as the man asserts ownership over the small house without first understanding its architecture or mapping its terrain. What’s more, his presence ultimately shapes what is possible in each of the rooms, limiting what can be attained in our dreaming, and determining the boundaries of our imaginative work.

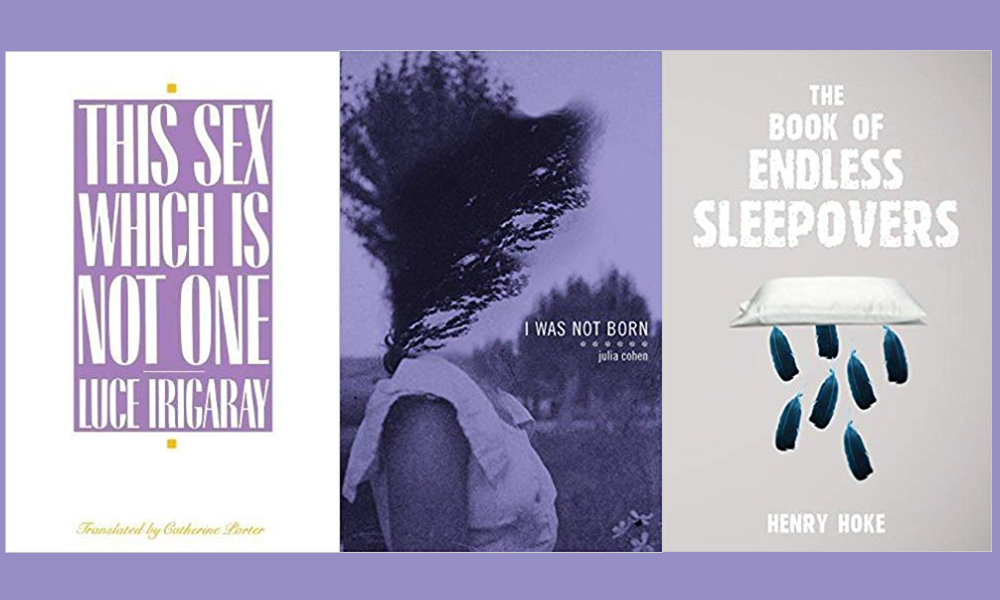

In the spirit of Irigaray’s unsettling psychological metaphor, two recent hybrid texts shed new light on these questions of power, agency, and the human psyche. Julia Cohen’s I Was Not Born and Henry Hoke’s The Book of Endless Sleepovers react against a long tradition of works that imagine the reader as passive and disempowered, only to be fundamentally changed by myths, images, and narratives he or she had no agency in creating. By presenting us with work that’s as participatory as it is deliberate, Hoke and Cohen posit their writing as a corrective gesture, framing the creative text as a space for readerly collaboration, dialogue, and collective experience.

This democratic impulse comes through most visibly in these gifted writers’ cultivation of silence, elision and rupture. By structuring their work in discrete, self-contained episodes, Cohen and Hoke show us that it is the space between words that sets off language, that allows us to see its shape more clearly, and to situate ourselves within its topography. After all, the poet Myung Mi Kim once said that part of collaboration — and the creation of community — is leaving room for the other to speak. Cohen and Hoke each relinquish some degree of control and ownership over their texts, if only to create a space for collective consciousness to emerge from the various fragments with which we are presented. As Hoke himself assures the reader, “this is an incomplete list.”

¤

In The Book of Endless Sleepovers, Hoke uses these carefully framed silences to involve and implicate the reader in the book’s portrayals of intimacy. “The water is stupid with stars,” he writes in an irreverent reframing of Mark Twain’s well-known stories of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. Here, Tom wonders if he is in love with Huck, and the reader is prompted to ask whether Huck actively contributes to — and revels in — what is in effect an unequal share of power.

“When the girls twist the stems of apples and the pop-tops of canned Coke they always end up on H for Huck. Never,” Hoke explains, “in the history of twisting girls, have they reached the letter T.” In many ways, he gestures toward Tom’s complicitness in this power imbalance, suggesting that agency resides in the creation of narrative. As the book unfolds, Tom ultimately disenfranchises himself through the grandiose and self-effacing stories that he constructs around his interactions with Huck: “Tom always asks the same question: ‘What time is it?’ And Huck always has the same answer: ‘it’s a little bit night and a little bit morning.’ Tom wakes at this time for the rest of his life.”

Yet by framing narrative as the creation of power, Hoke ultimately empowers the reader. It is the space between these prose sections, those bright apertures, that prompt the reader to participate in the process of creating meaning from the text, to actualize the book’s imaginative work. The text’s episodic structure, and its myriad silences and elisions, create a portrayal of intimacy that is as performative and participatory as it is innovative in its use of hybrid forms.

“Imagine yourself on a raft in a slow-moving river at night,” Hoke writes, “Every soft animal makes sounds from the bank. You are in the center of the raft, and surrounding you are all your friends, asleep.” These brief lapses into second person frame the reader as a constant presence within the narrative, an alterity that speaks through the text; Hoke’s use montage similarly creates a space for the reader to breathe into. In this respect, the reader is invited into the various power dynamics of the text, and at same the time, he or she is invited to change them. There exist as many possible texts as there are readers, and it is this multiplicity that contributes to the work’s sense of mystery. As Hoke himself writes, “to find out the secret, knock three times.”

¤

Cohen’s I Was Not Born offers a similar exploration of narrative, agency, and readerly participation. Presented as a series of linked vignettes, which take the form of therapy session transcripts, lineated poetry, flash essays, and hybrid prose, Cohen’s innovative approach to style compliments — and complicates — her chosen subject. Interrogating the death by suicide of the narrator’s romantic partner, Cohen’s book proves elliptical and palimpsestic in structure, presenting the reader with the impossible task of creating meaning from a tragic experience.

“Born in a deadlight? Stop teasing,” Cohen writes, “Furnace full of patient stars. Here because I could not abandon love: coffee grounds, a box of opened cereal, cherry magnets.” Here Cohen’s wild associative leaps prompt the reader to forge connections among the various ephemera that surrounds the narrator: “coffee grounds,” “cereal,” “magnets,” and of course, “stars.” Much like the book’s gorgeously fractured structure, Cohen’s dream-logic calls our attention to the conspicuous absence of exposition, reminding us that narrative is how we derive meaning from experience, that it’s the stories we tell that make us ourselves. These silences, then, speak to the absence of apparent meaning in the wake of tragedy. Yet at the same time, the reader is reminded of his or her own expository impulses, particularly as he or she fails and fails again to create the lovely arc of story.

Reading, then, becomes an exercise in empathy, as Cohen challenges the reader “To hold nothing against nothing. To hold nothing against.” Like Hoke’s work, I Was Not Born calls into question common ideas about the power structures implicit in the act of reading. Here, too, the reader is empowered by the work’s various silences and ruptures. Yet at the same time, he or she is made to see the abject futility of the agency with which they are afforded.

The reader, like Cohen’s narrator, falls “out of architecture,” finding only “a cut-up star.” In her study of grief, Julia Kristeva describes melancholia, that “pathological mourning” originally theorized by Freud, as a loss of language. Without a grammar for our experiences of the world, we lack meaning, cohesion, and purpose. Cohen skillfully involves the reader in this struggle to reenter language, and in doing so, reclaim the stories define us.

¤

If a readerly participation requires the writer to relinquish some degree of power, how can ever one trust one’s audience? In The Book of Endless Sleepovers and I Was Not Born, we are offered an opportunity for collaboration that is as deliberately orchestrated as it is rich in imaginative possibility. By carefully guiding the reader’s imaginative work, Hoke and Cohen present us with incisive arguments (and counterarguments) about how culture imagines the act of reading. As they renegotiate the power structures implicit in our interactions with literacy works, Hoke and Cohen ultimately offer a textual terrain that is at once performative, participatory, and carefully controlled, gorgeous in both restraint and interpretive richness. It is the silence that allows us to see these possibilities, these bright apertures, in sharper relief. As Cohen herself reminds us, “We write poems on the whiteboard of a cloud.”