When Kate Harris was 17 years old, she wrote an impassioned letter to 22 world leaders, imploring them to send humanity to Mars. We have the technology, she told Bill Clinton, Jean Chrétien, Tony Blair, and others, but we lack the political will. Her dream, she told them, was to travel to the red planet and find new knowledge, to inspire young scientists and push the boundaries of possibility. Earth had been mapped, space was the great unknown, and she was determined to explore it.

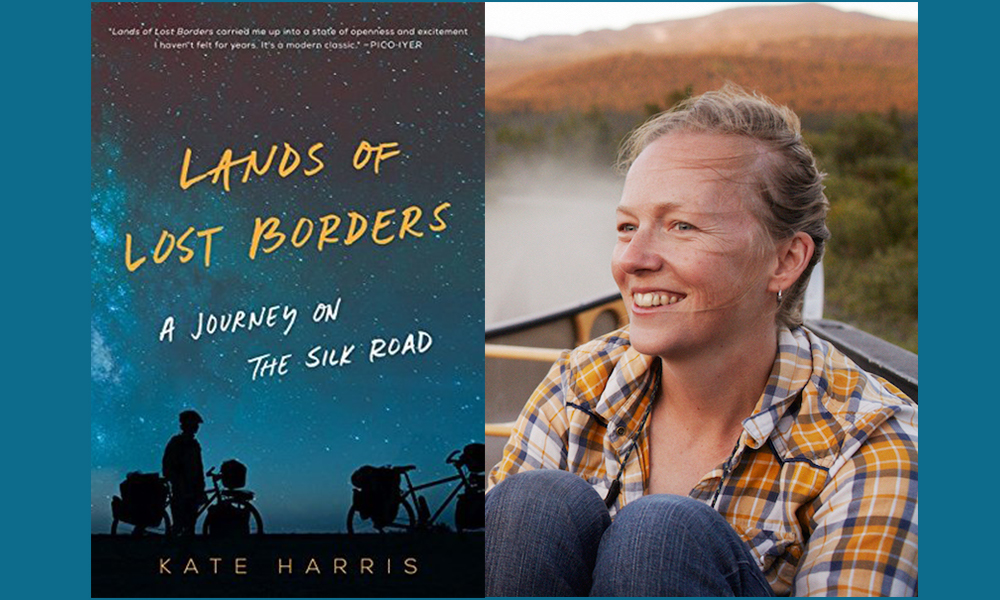

Somewhere along the way, that changed. Kate went from small-town Ontario to studying the history of science and exploration at Oxford, to a PhD program at MIT, before shedding the rigors of academia and launching on a different exploration: a 6,000-mile bicycle journey along the Silk Road with her childhood friend, Mel Yule. The trip was an extension of her thesis at Oxford, which was a study of how borders define and impact wilderness, and the basis for her debut book Lands of Lost Borders: A Journey on the Silk Road.

Before I met Kate, I’d long heard the legends. An off-the-grid, badass cabin dweller. An adventurer who had reached all seven continents, including a research trip to Antarctica. Canadian Geographic named her one of“Canada’s greatest modern women explorers.” These were not titles she had asked for, at least directly, but word spreads fast in the Yukon, where I was living at the time, and where many end up after an adventure of their own.

Our paths eventually crossed last May, not in Northern Canada but in Toronto, where her partner, also named Kate, teaches in the global environmental politics stream at a local university. I spotted her across a bustling coffee shop and even though we hadn’t met, I knew right away it was her. A plaid button-down over a Yukon Brewing Company t-shirt was the giveaway.

She had just returned from an assignment in Norway, where she was sailing choppy seas and bombing down mountains with former Olympic skiers. She was a few days away from returning to her cabin in Atlin, the remote sliver of northern British Columbia where she spends most of the year. Atlin is a place of community and art and nature and exploration. For Kate, it’s also a place where writing comes easier.

Now she’s working to shed those previous titles. She wants to be known for her words, not just her adventures. Gone are Marco Polo and Magellan. Explorers have been trumped by poets in her hierarchy of heroes.

Though she no longer yearns to reach Mars, she speaks often of the overview effect, the phenomena described by astronauts after returning from space, where, after viewing the world as a whole — without our entrenched divisions and political boundaries — they return home with a renewed sense of connectedness and greater capacity for empathy. She’s not convinced we need to leave this planet to generate that awareness.

In the end, her letter to the world leaders didn’t lead to a trip to Mars but it did earn a prize package, which included an 8-inch Bushnell telescope. With her father’s help, she set up in the backyard and, leaving earth’s borders far behind, peered into the great expanse. The humble beginnings of a journey that would eventually lead to the Silk Road.

¤

SAM RICHES: Maybe a good place to start is the first line of the book — it really sets things off perfectly. “The end of the road was always just out of sight.” Did you agonize over that sentence or did it come naturally?

KATE HARRIS: As soon as I wrote that sentence, I was like, yep, that’s how it starts. The proposal that sold for my book looked very different from the final book, but some sentences rang through all those versions, and that was one of them.

Initially, when I started writing the book it was a bunch of smaller, thematically connected travelogues. It began with the first pedal stroke in Turkey and it ended in northern India with the last pedal stroke. It was very linear. Then I started to weave in more and more with each draft.

That early version had the theme of borders running through it, and in retrospect it came across as very arbitrary. It was like I had chosen this theme and then gone on this bike ride in order to write a book, and, knowing nothing else, the whole project could seem academic and arbitrary. One agent — the one I ended up working with — really pushed me, asking, why borders? Why that particular theme? Then I explained some of the backstory: that I had spent two years studying borderlands and the role of science in precipitating and easing conflict; that initially I was drawn to science because of wanting to be an explorer and thinking Mars was the only place left to explore. He kept pulling the backstory out of me, saying that should go in there — otherwise, it’s an impersonal, arbitrary-seeming journey. And he was right. So I hid away for another two years and tried to tell that bigger story, which veers off into space and all the wacky dreams I had that led to the Silk Road and this book.

The notion of community, and expanding community, runs through the book. We meet these families along the way that take you in and are so generous and welcoming, but on the other side of that, you’re travelling through these areas that have the reverberations of colonialism, dictatorships, oppressive regimes, people that cannot leave. How do you balance that?

I will never have enough lifetimes to pay forward the generosity Mel and I received on the Silk Road. The fact that that generosity came from people with so much less is an uncomfortable balance. It’s a weird tightrope that any tourist walks, but especially when you’re travelling by bicycle and people do really open their lives to you in a way that you don’t get as often on the beaten track. It’s an uncomfortable position to be in but it’s also a place of incredible exposure and fortune, a chance to see lives that you wouldn’t otherwise.

I certainly carried around this guilt, especially in places like Tajikistan, about having the ability to leave, having a passport that is meaningful in the world, having opportunities. Here, I’d shunned an incredible opportunity to be a scientist and do a PhD. In Tajikistan, we encountered a botanist lady who would have killed for that chance. She’s struggling to live out that kind of life in a country where it’s not really possible. There’s no hiding from your extreme privilege when you travel. It’s a question of what you do with that awareness.

While writing the book isn’t giving anything back directly to any of the countries or any of the people that helped out along the way, the one thing you can do as a writer is make people aware of, and hopefully care about, parts of the planet they’ve never even heard of. If you can do that, then when something comes up in the news about civil unrest in Tajikistan they’re alert to it, and they might care a little bit, however tenuous the connection. But again, that only ends at awareness. I don’t know if that translates to action, if it translates to a better world. It’s hard to say.

I think the beauty of travel, at least part of it, is that you come home with very different notions for how it’s possible to live and how little you need to live well. It’s kind of a cliché, I guess, and maybe even a dangerous one at that, this idea that material wealth isn’t everything. You meet people that, from my superficial understanding of their lives, seem to have something a lot of us in North America are lacking, something money can’t buy, like a sense of belonging or community. At the very least, anyone who has gone on a trip like ours couldn’t come home and get a job at a bank and prioritize money over all else. It’s just an impossible reaction after experiencing the world the way you do on the back of a bicycle.

You have a great line about the idea of travel: “The true risks of travel are disappointment and transformation: the fear you’ll be the same person when you go home, and the fear you won’t.” It seems so often that we think that we’re impervious to change or even fearful of it, but we’re not realizing that we’re all changing every moment, every day, all the time. The person you were five years ago is probably not who you are today. Why do you think embracing change is difficult for so many?

Change is scary. We love to think we’re in control and travel exposes the fact that we’re not most of the time. It’s kind of a beautiful surrender to having no control over your life. You’re thrown into this new place, with new ways of communicating, and you realize it’s not such a bad thing to not know what’s going to happen every hour of every day. To wake up and not know where you’re going to sleep that night, or who you’re going to meet, or what you’re going to see.

I think that getting comfortable with change during travel can carry over into life back home. You’ll be less likely to cleave to security and comfort. And it’s often the experiences that you don’t anticipate changing you that change you. Or change you in ways that only rear up on you years later. Travel as instant enlightenment or accelerated enlightenment is unrealistic.

Throughout the book, we are reminded that the more you see of the world, the more you can connect, or better understand, your own experiences. That, in many ways, travel shrinks your world.

And connects the world — connects these far-flung dots that you might not otherwise see as related. Literature can have the same effect. Travel in words can be extremely powerful, maybe even more so than a typical touristy trip.

Think of a desert. Growing up in Ontario, as we did, you probably can’t get further from the landscapes that we were used to then in the deserts of Central Asia or the Southwestern US — such alien landscapes, relatively speaking. It would be very easy, based on what we know here, to dismiss such landscapes as barren or as wastelands — all the language thrown on such wildernesses over history based on people’s biased ideas of beauty. But words I read long ago had already implanted a deep love and longing for mountains and deserts and landscapes I had never seen. I read work by writers who revered them, did not dismiss them as worthless, revealed them as sublime and alive in their own unique ways. Exposing those connections is almost like cultivating an emotional capacity for metaphor in landscape: if you fall in love with one desert in the American Southwest, you’re more likely to appreciate another in Chile. If you fall in love in with a small patch of forest you grew up with in Ontario, you’re more likely to value similar forests elsewhere.

Because of their ability to transport you and open up new possibilities?

Yes. They change your heart. They make you see the world in fresh, interesting new ways. I hadn’t ever seen a mountain or an ocean until I went off to university but I had visited them many times in books and felt this connection with them that was based only on reading. But it meant these landscapes had resonance for me when I did finally see them. I was primed to appreciate mountains and deserts and oceans because of what I had read.

What about change within yourself? Now, some time removed from this trip, how have you changed?

When I went on this trip, I was running away, or running toward, a different life than I had led before: namely from a life of exploring the world through the lens of science to getting to know it in other ways, writing in particular. I was so critical of Darwin in grad school, about him settling down in a countryside cottage and having a bunch of kids and never travelling anywhere ever again. The idea of staying still used to feel so inimical to me. I got a bit of that wanderlust out of my system on a trip like this. By the end of the ride, I was so ready to come home and have conversations that weren’t superficial. When you don’t speak the language it’s hard for exchanges to be anything but. There’s so much you miss when you’re traveling to a new country every month. You never really get to know any place with any depth. You make new friends and leave them behind forever every other week. It gets exhausting after a while.

Now, somewhat ironically, our cabin is kind of like Darwin’s countryside cottage. We don’t plan on having ten kids or anything, but the idea of exploring in place is way more appealing to me now, of really getting to know a place, or more accurately coming to understand that you can never completely know a place, no matter how long you’re there. The longer you stay somewhere, the more you learn to recognize and celebrate the subtler changes and wonders of the world around you all the time, as opposed to travelling, when everything that comes at you is brand new and dazzling. There are other novelties you can only recognize once you have a baseline for seeing them, once you’ve been somewhere a long time, and that’s a kind of exploration too. I guess I’m far less of an extremist now in terms of how I see exploration as the sort of thing that can play out in meaningful ways in everyday life, not just in big, glamorous expeditions.

Our lifestyle at the cabin has certainly reinforced for me the idea that you only just need enough to be happy. An extravagance of things — even of money, I imagine — is a burden. Of course, a little more of a burden in terms of extra cash might be nice on occasion, but it was sort of our mission with the cabin to be as divorced as possible from having to make a lot of money. We’re still paying down a mortgage, but when that comes to $350 a month and you have basically no monthly bills because you have no electricity, you can live a pretty rich life on very little. When my partner Kate was a postdoc and I was a writer who hadn’t written anything, we were living out there on a combined annual income of $30,000 and we could live so well on that, it gave us all the time in the world to write and think and wander outside. I wonder, too, having seen the ways so many people live around the world, what right do I have to just accumulate things? So many are living with way less, with less choice in the matter.

Do you feel people recognize you now as a writer, an author, and less of an explorer? Is it difficult to navigate those titles?

One of my fears about the book is I’ll get pegged as an adventurer and I don’t feel that way. I’ve been called that — explorer, adventurer. These are not self-appointed labels. A question I get a lot at the end of book events is, what’s next? And they don’t mean it in a literary sense. They mean what’s the next adventure. I understand why they ask, even as I recoil a bit because I first and foremost see myself as a writer. The biggest adventure and the deepest exploration for me is the writing, not the journey itself. It’s the coming home and trying to bring an experience or insight alive on the page, in language that sings.

Being pegged as an adventurer versus a writer is, well, whatever — people can call me what they want. As long as I get to keep doing what I’m doing I’ll be happy. What I’m most excited about right now is being part of the community in Atlin, getting our garden going, building a better greywater disposal system, just keeping life cranking out there with the goal of being as self-sufficient and divorced from the usual economies of the world as possible. I want to write something in that direction. Not another travel book, not another point to point trip account, but something more meandering, like poetry in prose. I love poetry. Poets are the ones I worship now, more than Darwin and Marco Polo and explorer types.

That’s the beauty of Atlin for me. I am a restless person in every respect and this place both accommodates my restlessness and gives it a weird rootedness. I can be restless in place. I will never be bored there. Right behind our cabin, there are countless mountains I’ve never laid eyes on beyond the ranges I have seen. Wanderlust gone local is the vein I want to tap for a while.

Can you tell me more about the Mars letter and the passion you had at such an early age for space exploration?

I had this acute sense that this world was done in terms of exploration. The most travelling my family ever did was car camping trips to Georgian Bay. When all you know of the world is concrete and fences and farm fields edged by subdivisions and the occasional provincial park, it’s pretty easy to extrapolate that kind of tameness across the whole planet, especially when you look at maps and see lines and roads all over them. I really thought the only realm left where someone could give expression to an exploratory spirit was off this world.

My dad gave me a book, The Case for Mars by Robert Zubrin. Zubrin was the founder of the Mars Society, which is how I found the contest for writing that letter petitioning world leaders to send humans to Mars. The whole notion enchanted me. I read a lot of science fiction as a kid — Ender’s Game, Asimov, Kim Stanley Robinson. My dad was into all those writers, so he fed them to me. Mars compelled me the most because it’s a place we can actually go and leave footprints. A human can walk around there, and it’s more exciting than the moon in that it could have been or could again be a living, breathing world, with water and a thicker atmosphere. This was thrilling to me as a teenager looking for meaning, for an outlet to my restlessness. I get really obsessed with things, at a deep level, but then I get obsessed with something else a few years later — ideal for a writer, I guess. But my childhood obsession was space. I was gunning for it. That’s why I studied so hard in school. I just wanted to launch out of this world.

In the book, there’s this low point in Tibet, where you write that you hope we don’t go to Mars. Do you still feel that way?

I still feel that way. I love living in an age in which we are sending rovers to Mars and orbiters around Mars that are revealing super cool things and potentially yielding insight into that age-old question, are we alone in the universe? That is pretty thrilling to me, on an existential and an imaginative level.

That was a part of the attraction of Mars as a kid. As you grow up, the adults around you seem to have all the answers. You wake up, you play, you have dinner, your parents look after you, and then you slowly figure out that nobody has a clue what we’re doing here, what life means. We’re all just playing this game with rules we’ve mutually agreed upon and the economics the modern world enforces, but we don’t know why we’re here.

I’ve always had a spiritual bent. It’s never found expression in religion, per se, but more so in science, in looking at the stars and wondering about our place in the big picture. Mars was very much that for me as a kid — spiritually thrilling, and still is to an extent. But I don’t think it’s the most important thing that we send people there. There’s so much we can figure out with scientific missions, robots, rovers, and orbiters. Putting a person there, as the highest priority of humankind right now, seems really skewed when you look around at what we’re doing to this planet. It would be this nationalistic, ego-boosting move, much like putting a man on the moon was in the sixties, which was thrilling, and inspired a generation of kids to try to pursue science, but what are we left with from that? We have photos of a man on the moon, some rock samples. There is so much terrible stuff happening on this planet and we couldn’t live on Mars if we wanted to, not with current technology. We don’t know how to create or sustain a second biosphere, even on a small scale. We’ve failed at that again and again. I think it’s telling that people like Steve Bannon were big investors in the Biosphere II project, these men who think the world is going to hell and seem to encourage it in that direction. But they’re also trying to hedge their bets, ensure they have an escape. It’s dangerous thinking. We can’t abandon ship. We have to put everything we have into making this one world work.