By Austin Park

The (Un)Draped Woman is the third in a series of pop-up shows organized by Roshi Rahnama and Advocartsy, a “collaborative visual arts platform” examining an exciting and highly active Iranian contemporary art scene in Los Angeles and beyond. This particular iteration seeks to challenge and interrogate the established or conventional image of the woman in Iranian culture, a central visual aspect of which is the image of women in various states of cover. Virtually all the works in this show engage primarily with questions about the image of self or the self-portrait. In this sense, the show as a whole attempts to visualize a contemporary Iranian and Iranian-American image of feminine self, ones that might possess qualities and inspirations from both Western and Eastern culture.

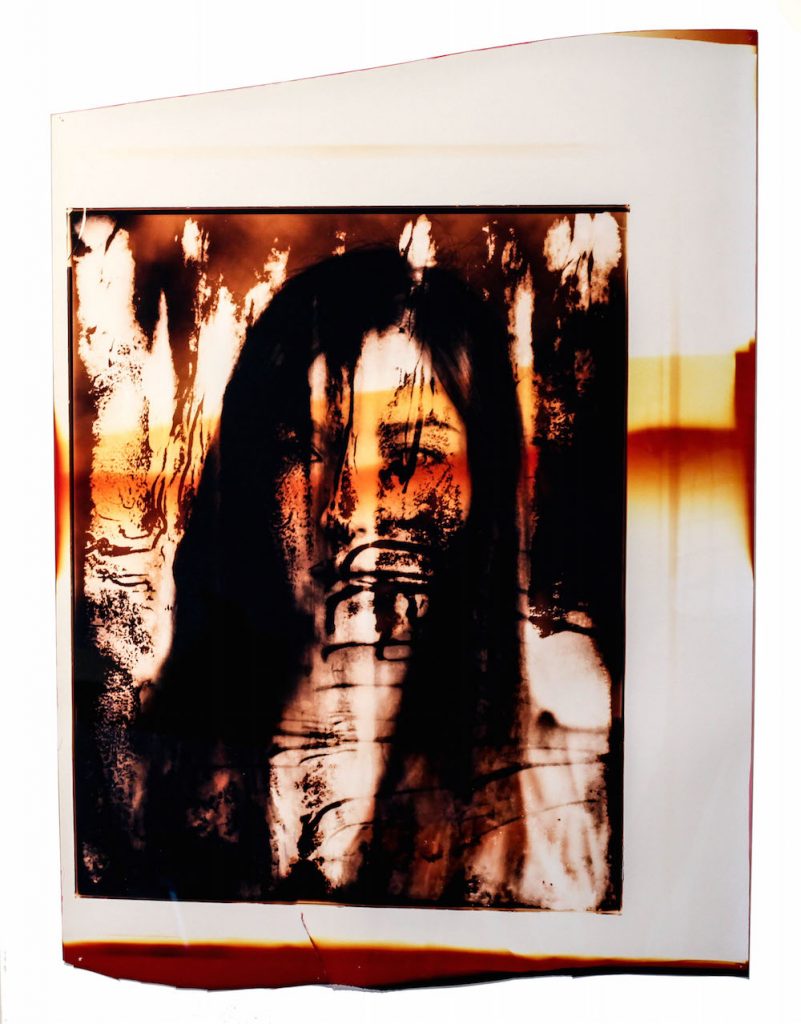

In the layered photographic print work of Hadi Salehi and Shadi Ghadirian, interest in emphasizing and activating the surface of the picture itself and its relation to the portrait is an important formal technique which probes the limits of literal representation, and the image as true and definitive expression of self. In the two photographic prints from Ghadirian’s Be Colorful (2002) series, women in garb and hijab are as if trapped behind a foggy glass window. Their presence is incredibly immediate, almost hyper-real, and yet interrupted by an impenetrable invisible barrier that is the very surface reality of the image. The woman’s presence is limited by the “front” of the photo itself; she is trapped within the image, yet also more present that in most conventional images. These prints recognize a limitation of the image, and yet also succeed in getting closer to the viewer, exerting a presence within our space.

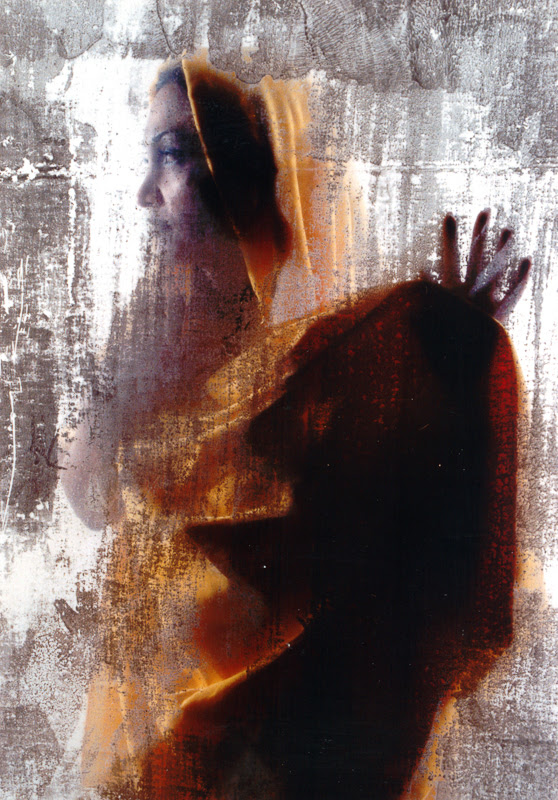

The picture’s surface is similarly emphasized in Hadi Salehi’s prints, in which images and photographic processes seem to be layered on top of one another eliciting an elusive and ghostly effect, simultaneous to a highly textured and tangible experience. Things seem to appear out of and disappear back into the dense textures of the large-scale photographs producing the effect of a moving and changing picture akin to a Robert Rauschenberg print collage. The beauty with which Salehi renders the “flaws” of analog photography (over-exposures, literal burning of film, and other stretches and abstract expressive gestures) transforms the surface reality of the photographic image into a landscape in which the photograph as literal and true representation of reality is made mysterious and spiritual again.

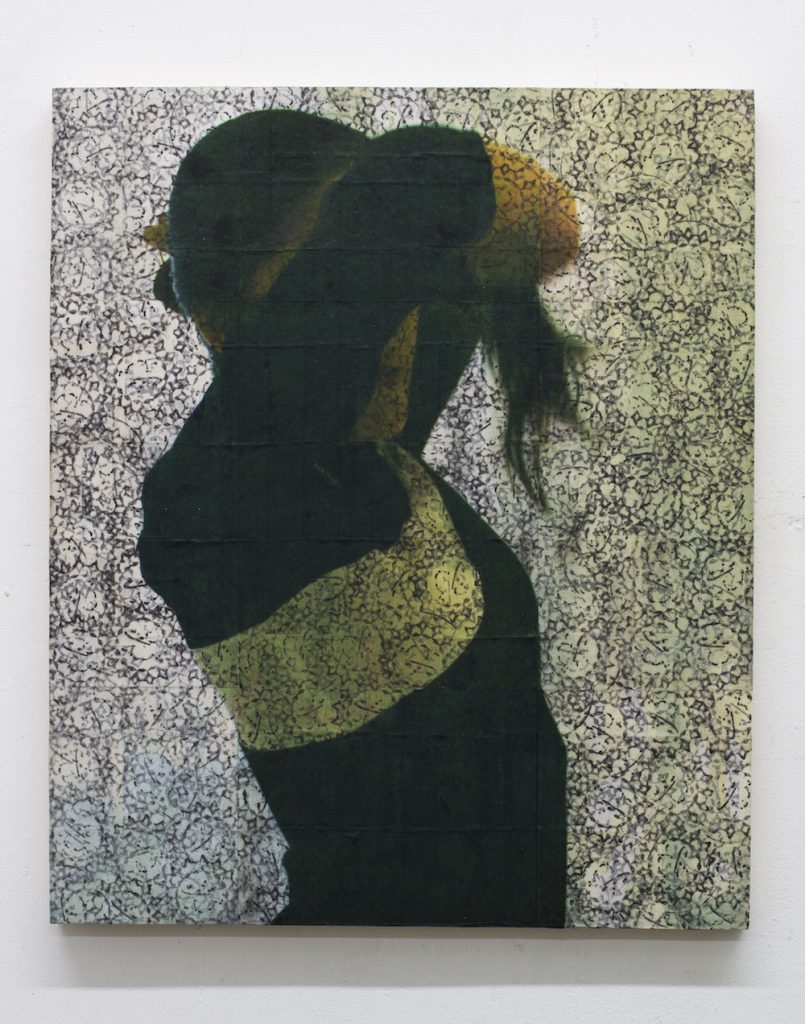

Perhaps the most directly related to the show’s stated theme, Sepideh Salehi’s Mohr Portrait (2015) is a series of 10 photographs staggered across the back wall of the central gallery. The photographs are mounted on wood panels and printed on Japanese paper. They illustrate a number of different poses that in one way or another obscure the eyes of the figure and emphasize the body and hands in various poses. This denial of the visibility of eyes as the conventional “window into the soul” expresses a different kind of self-portrait, one that poses states of mind, thought processes, and actions attempted and coming into being as an equally if not more valid marker and representation of the self as the woman’s gaze. The image of the woman, so often fetishized, idealized, and put on display for the viewer’s (often male) gaze in advertisement, popular culture and in Western art history, is re-claimed by the subject in these photographs.

A self-portrait by San Francisco-based Shadi Yousefian, called Social Identity (2003), is a large photograph collage triptych scaled roughly to the actual size of the artist’s body. The artist appears as herself in three different coded appearances. On the left, she appears as what curator Sandra Williams describes as the “quintessential ‘Cali’ girl — tank top, strappy sandals and a flower in her hair.” In the center, her face is in heavy makeup and her body is a rough collage resembling a Barbie doll. On the far right, she appears in head scarf and garb “typical of a young woman in Iran.” What is striking about the piece is the lack of judgment that is passed between the three appearances. All three images are put on even keel, and the cut, pasted, and recombined quality of the images seems to encourage the viewer to re-create and re-assemble the “true” or authentic identity and representation of the artist for themselves between these three appearances. The limitations of the image to represent female and specifically Iranian or Iranian-American identity is again brought into focus. Particularly, Yousefian’s work addresses both gender and ethnic identity head-on and at eye-level, ironically inviting the viewer to measure “by ruler” the suitability and authenticity of the artists’ proportions and appearances.

The show evoked a wide array of contemporary art styles, such as the “sublimely superficial” style of an Alex Katz portrait in the paintings by Toronto-based painter Simin Keramati. The interjection of an Iranian female subject into what is essentially a reproduction of an Alex Katz painting felt not wildly original, formally, and yet not merely derivative, either, especially given the theme of this show. Alex Katz’s work is usually associated with an affection for the sensation of appearance, utilizing aspects of the simplified language of pop-cultural imagery while retaining an utterly personal and specific quality. They are a celebration of the personal within the American and Western pop-cultural visual language. Likewise, Keramati’s Sun Glasses (2009) and Hush (2008) seem to celebrate, and derive pleasure and a sense of self-identity from, Western pop culture while retaining a quietness, and specificity that can be seen as an admiring homage to the “pop serenity” of an Alex Katz portrait.

The (Un)Draped Woman presented a diverse group of works that were highly communicative, fluid, and well contrasted in relation to the theme of the show and opened up new solutions to the age-old question of self-portraiture and self-representation in art history. A consistent pulse throughout the show was that of these artists claiming the image not as an irrevocable and absolute “true” representation of reality, but rather of the image as a workshop, a site of contest, production, conflict, discussion, and experiment, in which identity is constructed and built in various ways. There was also a consistent evocation of the sacred nature of the image, and how the representative image is insufficient to what the artists want to express about the negotiation between Iran and Western cultures, between a rich and time-tested cultural history and the forces and new possibilities of the Western world.