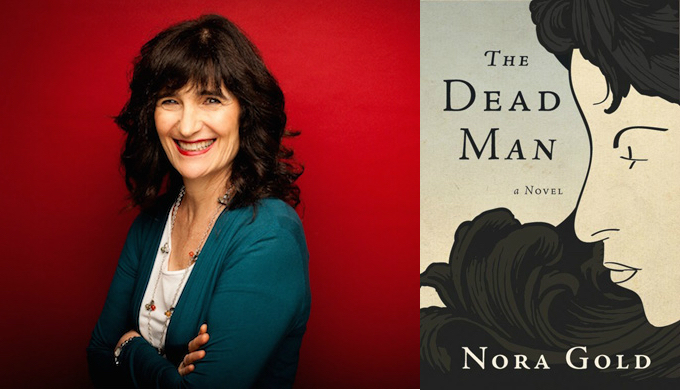

If you believe in the value of travelling beyond one’s comfort zones, you’ll find much to support your belief in Nora Gold’s most recent novel, The Dead Man (2016). Gold is a Toronto-based writer who has a history of venturing into fraught terrain. Her first novel, Fields of Exile (2014) — she debuted with a short story collection that won praise from Alice Munro — dealt with anti-Israel sentiment on university campuses, which marries all too well with outright Judeophobia. The Dead Man, Gold’s second novel, examines the erotic longings of elderly men, obsessions of women deep into their middle age, and creative impotence. Throw in widowhood, manipulative stepmothers, needy wives, and therapy (music therapy, but still…), and you have a cringe-worthy melange that pushes almost every reader’s buttons. Yet it is precisely by adventuring in such difficult emotional terrain that Gold achieves something beautiful, transformative, and life-affirming.

Gold’s heroine, the 55-year-old Eve, is a Jewish Canadian composer who, despite some early success, is unable to get her music out into the world. As it happens, she is also a stalker, haunted by a brief relationship she had five-and-a-half years earlier with Jake, a famous Israeli music critic then just entering his old age. Although Jake brusquely cuts her off when he realizes she could cost him his marriage and his comfortable life, Eve hopes to restart the affair on whatever terms he finds acceptable. She calls him compulsively, only to hang up, and ultimately travels to Israel in hopes of connecting with him.

Eve is also a music therapist. In a classic case of physician heal thyself, she tries to apply everything she’s learned in therapy to understand both Jake (presenting him, at one point, as a case study in a therapy seminar) and her own needs and compulsions. Eve’s external and internal gaze is both unflinching and compassionate. When they become lovers, Jake is concerned that his wrinkles, his oldness, will be turn-offs for Eve, and, in truth, when she first sees his body — “old, bony, desiccated” without a single hair on it — she wants “simultaneously to laugh and to vomit.” But — as she tells him later — she doesn’t look at his age, but at his essential self. It turns out, however, that what she’s seeing isn’t only a heavily idealized version of Jake, but also her projection of everything that she was given and denied as a child. In a nice twist, after looking at an old photo Eve is shocked to realize that Jake’s mouth is identical to that of her mother, who died when Eve was just a toddler, and that the intensity of her grief at being abandoned by Jake (and, perhaps, her initial attraction to him) stems in part from her longing for her mother.

The figure of a lecherous old man who is attracted to “young flesh” (actually, these are the words Jake’s jealous wife Fran uses to describe Eve) is at least as old in English literature as Chaucer’s “sir old dotard,” who lusts after the young Wife of Bath. Jake, however, resists easy categorization. He might well be a psychopath, as Eve’s seminar leader insists, and he might well have needed Eve as an erotic symbol, or, more darkly, as a weapon for him and his wife to hurt each other with — the third “razor-sharp edge” to their triangle. All the same, his flaws and his needs (from his lonely, difficult childhood onward) make him all too vulnerably human, and it is clear that the role Eve played in his life was also multi-faceted, involving deeper feelings on his part than just lust. He might have made Eve into a symbol, but then he was a symbol for Eve too — a symbol of everyone she wanted to stay close to and of all the losses she had to weather in her life: the sudden death of her mother, alienation from her father (thanks to an evil stepmother), and the loss of her husband, who died of a heart attack at the age of 42. When Eve is finally able to lay the relationship with Jake to rest, to allow Jake to die (metaphorically speaking), she is finally free to mourn all the people she loved and lost but never fully let go.

Both Eve and Jake are Jewish, with a strong connection to Israel. Jake had settled in Israel as a young married man, Eve has family in Israel and has considered (and still considers) immigrating. The meaning of Jewishness, whether as a marker of personal identity or of a category of art (Jewish music and Jewish painting), is an important subtext in the novel. Once again, Gold cannot be accused of reductionism — Jewish identity is presented in all its many contradictions (she is, among other things, the editor of Jewish Fiction. net where she must have many firsthand opportunities to see the complexities of Jewish identity at work). Jake, who is religiously indifferent, disapproves of Eve’s active faith; she attends a synagogue where there is no cantor and where women can also lead the prayer services. But Eve’s faith does not lead her to question the ethics of her relationship with a married man. There is no end to bad Jewish art — ditto for bad Jewish music: Eve is disgusted to see junk art displayed in an Israeli art gallery, what she calls “the seventh-rate imitation of Chagall”; Jake hates the “utter mediocrity” of some Jewish musical compositions. Conferences on Jewish music proliferate, but Jewish composers have radically different views on whether there really is such a thing as a Jewish composer; one composer explains helpfully that he is not a Jewish musician, he is just a musician, to the ire of another composer who quips that she didn’t have to come to a conference to learn that Jewish composers are also human.

Eve, who does identify herself as a Jewish composer, has been struggling with a musical composition — a love and hate cycle, as she calls it at one point — based on her relationship with Jake. Parts of it won’t fit together properly and it has no conclusion. When Eve realizes, after much struggle, introspection, and recovered memories, that she is free of Jake, the conclusion comes by itself. She hears a mourning dove coo outside and weaves its song into her composition.

Indeed, one especially delightful thing about the novel is the close attention paid to the auditory landscape around Eve, the way voices, trees, and bird song become transformed into musical notes in her mind. At the very end of the novel, the taxi driver who comes to drive Eve to the airport has his car horn fixed up to sound like a Shofar’s blasts on the Jewish High Holidays — arguably the most ancient form of Jewish music. The blasts, sounded outside their original religious context, and played upon a non-instrument for a completely different function than originally intended, raise many questions and evoke rich associations, embodying perfectly the contradictions and the challenges of reinventing a Jewish art of any kind within a contemporary context.

More importantly, upon hearing the blasts Eve realizes, “Everything is music here. Everything is music everywhere.” Everything she experienced in her life — the losses, the painful relationships — enters the great musical score of which she is both the protagonist and the co-creator. Earlier in the novel, Jake criticizes another composer for concluding his composition by just tying it up “with a big phony bow. One of those pat, conventional endings.” By contrast, the conclusion of The Dead Man is anything but pat and conventional — it elevates and transforms all the events of the novel. It is as if Eve and the reader had travelled a tortuous terrain, paying attention to every step but not noticing that they were ascending. Now that the summit has been reached, the look back reveals not ugliness but beauty.