We were given a single day to anticipate Taylor Swift’s eighth album, folklore, and this is why, I think, I spent only a day really listening to it.

When Lover, Swift’s seventh album, was released last August, I streamed it equipped with the album’s lurid pink visuals and the unpleasant experience of hearing the singles “ME!” and “You Need to Calm Down” with disproportionate hope months earlier, in addition to the dullness of “The Archer” and warmth of “Lover.” I — and many, it seems — believed that Lover, in its sappy contentment and relative lack of punch compared to Swift’s arguably boldest prior album, had marked the conclusion of the megastar’s persistent and conspicuously evolving oeuvre.

While skimming publicity for folklore without any pre-released singles to whet my tastes, I was unexcited by its premise: a collaboration with guitarist of The National Aaron Dessner, whose presence on the album makes no apparent difference; a track accompanied by Bon Iver, a disappointing and perhaps lazy gesture to justify the record’s supposed folkiness; and a plethora of fabular songs recorded — surprise — in quarantine.

The most provocative part of folklore preceding its release was its visual aesthetic, as has been the case for Swift’s last few albums ever since she stepped entirely away from country into various subgenres of pop. Brief articles announcing the new album included images of Swift in a white dress and cardigan, standing whimsically in various woodland locales. Shot in black and white, the photos evoke the girlish, “boho” nook of last decade’s Tumblr, with Swift wearing space buns and various cottagecore garments: a loose, lace dress, an oversized tweed coat, a thick knit turtleneck. Like that of Lover, folklore‘s album art not only reveals yet another transformed Swiftian aesthetic — as updated on all of her social media platforms — but also takes clear inspiration from already popularized aesthetics; it is curious that one with as great cultural influence as Swift routinely chooses to inhabit the styles of others when she could easily pave her own path with sweeping reception.

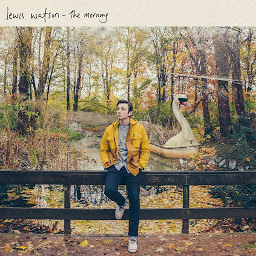

At first glance, folklore’s cover evokes, in monochrome, English singer-songwriter Lewis Watson’s 2014 record “the morning.” The tracks also appear to co-opt his — and many indie and alternative artists’ — stylistically lowercase titles. The scenery and fashion of folklore also remind me of The Head and the Heart’s self-titled album from 2011, from which the anthemic “Rivers and Roads” gained wide attention. Despite its titular and artistic presentation, however, Swift’s new record is neither folk nor indie, really, in the way that, say, Lewis Watson, The Head and the Heart, and Justin Vernon so evidently are. Swift hardly remolds her former sound; she simply cools it down and glazes it over. The songs on folklore, with largely predictable chord progressions and melodies, are wistful and unspectacular, appreciable but hardly commendable attempts toward fantasy and sheen. While less aggressively pop than Lover, reputation, 1989, and Red, folklore still lacks the crudeness of successful contemporary folk: a stringy timbre, tenderly rousing vocals, and pure emotional force.

Like many of her musical contemporaries, Swift has already proven pop to be capable of reflection and emotional impact, and her pivot here toward a more unassuming “indie” sound feels somewhat gratuitous. “the 1,” the album’s fine opener, is a slower, gentler, and yet no more earnest or vulnerable successor to Katy Perry’s upbeat and similarly themed “The One That Got Away” from ten years ago. Perry’s lyrics are more impassioned and regretful — “I should’ve told you what you meant to me / ‘cause now I pay the price” — while Swift’s appear intentionally ambivalent toward a lost lover: “I persist and resist / the temptation to ask you / if one thing had been different / would everything be different today?”

Coproduced by Jack Antonoff (of bands fun. and Bleachers), who has worked with Swift since 1989, folklore espouses an overrefined and less ingenuous version of established indie folk. folklore comes closest to achieving its desired sound in “invisible string,” “seven,” and “august,” tunes led with sugary strings and Swift’s at times searingly soft vocals, climbing to pleasingly high tones. On the chorus of the former, a poignant celebration of destiny and reconciliation with past pains, Swift sings:

Time, curious time

Gave me no compasses, gave me no signs

Were there clues I didn’t see?

Isn’t it just so pretty to think

All along there was some

Invisible string

Tying you to me?

There is also a sweetness to “betty” — perhaps due to its personal, epistolary style — reminiscent of older fan favorites like “Dear John,” “Ronan,” and “Hey Stephen.” The incrementally descending chords, following the same sequence as those in Pachelbel’s “Canon in D,” resound comfortably and finally mount a key change, a method common to early 2000s pop raising the intensity of a song as it approaches its end. “betty”‘s ending ironically may be the closest thing to a climax that any song on the record possesses. One might argue that this is the point of the album, its shirking of conventionally climactic pop, but while folklore does achieve this, the dulcet tones themselves don’t quite suffice as an engaging listening experience, especially with Swift’s deeper, duller vocals in contrast with the higher and livelier voice holding center in her first three albums in such songs as “Invisible” and “Love Story.”

Nonetheless, fans and begrudging listeners of popular radio and guitar covers have, for the last decade and a half, clung onto Swift’s crisp, breathy voice as it has cemented into a sonic standard of pop music. Where she takes her voice (even as its luster dwindles), with each new release as its vessel, is where pop and the public’s attuned ear inevitably follow. If you try hard enough, you can enjoy something as decent as Swift’s music. And if you try harder, you might continue to like every addition, however unexceptional, to her discography. The explosive metrics of folklore‘s streams have only further demonstrated Swift’s, albeit weakened, resistance to Pop 2.0 — that is, the ever-expanding command of hip hop, bedroom pop, and sad pop on the charts.

folklore‘s immediate success or, in different words, Swift’s remarkably enduring acclaim inextricably rests upon a long-cultivated, 21st-century cult of personality. The Tennessee-primed pop feminist behemoth has dazzled to the point of seemingly impossible extinction, amassing an enormous, devoted fanbase and perhaps an even more dedicated swarm of attentive and anxious followers, be them fond, curious, critical, or hostile. The fact that Swift titled her recent career documentary Miss Americana, even if mindfully or ironically, supports the rather obvious notion that the gleaming, white-toothed, pale-skinned blonde from small-town Pennsylvania has become an emblem of some pervasive American sensibility. As a loyal Swiftie myself, I can understand why people don’t like her music if they never encountered her pre-Red or 1989; I don’t find it easy to separate today’s Swift from her past music. Her discography seems a necessary extension of her current identity, always appended to an existing (and industry-monopolizing) timeline.

Swift’s immense reputation cannot be discussed without mention of its (only partially) tabloid origins. She has notoriously racked up celebrity exes Jake Gyllenhaal, Harry Styles, Tom Hiddleston, and Calvin Harris among others, weaving a glamorous web of scrutiny in which we all have suitably been caught. The trickiness of folklore is thus that the album is, unlike all of Swift’s others, supposedly fictional: mere mythologies concocted by Swift in a somehow inspiring period of enforced isolation. The only drama to be gleaned from the record — for instance, the theory that her current (?) boyfriend Joe Alwyn used the pseudonym William Bowery to help her write two songs — feels cheap in comparison.

The folklore of folklore doesn’t feel too different, however, from the more diaristic stories Swift used to tell. Her previous music has perhaps been overstated with respect to its autobiographical nature; many of Swift’s songs, while certainly inspired by her lived experiences, take lyrical form in the romantic projections of a young person in like, lust, or sometimes love. Familiar themes and symbols emerge in folklore, with vanilla lines like “sweet tea in the summer” and “dancin’ in your Levis / drunk under a streetlight.” We just can’t ascertain, this time, who the gentleman in the jeans might be. Publicity on the album, as with Lover, has consequently wilted, increasingly wont to concern bland, trivial affairs within Swift’s largely elite circle of friends. “betty” unveiled the name of Blake Lively and Ryan Reynold’s third child; Swift mailed actual cardigans to at least 18 celebrity friends while the eponymous track climbed to the top of US charts on Spotify.

Freebies and fiction aside, folklore is still a satisfactory record. I’ll admit I enjoyed hearing Swift stray from her usual more upbeat pop, even if toward a somewhat tasteless sound, a few aforementioned songs aside. I’d like to see her continue to strive away from music that is familiar and easy for her and her fans, and to expand the genres on her palette while continuing to bring listeners alongside her ongoing story. I spent only about a day on folklore — I wasn’t compelled to stick around — but am eager to hear what will come next. My love for Swift is near-unconditional, as though she and her art are essential channels through which I might better understand myself. To accompany Swift on this journey, however tumbling or trite at times, is as much a self-revelatory act as a continuous introduction to good — hardly great — music. After listening to folklore I returned to each of her past albums and even unearthed a few songs I hadn’t yet given a full listen. I am following her oeuvre as it unfurls, wrapping myself when needed in the warmth of her older songs.

In one of my favorites, from the breakthrough 1989 of six years’ past, Swift opens with the following lines:

Looking at it now

It all seems so simple

We were lying on your couch

I remember

You took a Polaroid of us

Then discovered

The rest of the world was black and white

But we were in screaming color

And I remember thinking

Are we out of the woods yet? Are we out of the woods yet?

Are we out of the woods yet? Are we out of the woods?

Are we in the clear yet? Are we in the clear yet?

Are we in the clear yet? In the clear yet? Good

folklore marks the seasoned pop star’s timely retreat into the forest, into the quaint black and white which she once chose to brush aside for the gleaming city. Only this time, she has imbued the woods with pleasing myth and meek intimations of new directions.