On January 7, 2020, the retrospective of Colombian-American painter Lari Pittman closed its doors at the Hammer Museum. It is difficult to envision when the next exhibition containing a similar breadth of insights into the roles art may play in the contemporary moment — both as a practice of making and one of seeing — will open, especially now that a global pandemic has brought the art-world to a standstill. Taking up most of the Hammer’s top floor, the show was the most comprehensive survey yet of Pittman’s work, a groundbreaking exhibition in a career landmarked by them. Pittman’s work had always been relevant and prescient, if off-kilter from the succession of dominant languages within which American contemporary art understood its own history. In this triumphant retrospective, Pittman’s work appeared as if the world had finally caught up with it, and, strikingly, shed some light on the realities and limits of contemporary models of artistic production, right before Covid-19 unsettled our sense of the perenniality of these models.

The history of Lari Pittman’s birth into his own distinctive approach towards painting is practically myth by now but is nonetheless illuminating. It starts in CalArts, where Pittman studied for both a BFA and MFA, graduating respectively in 1974 and 1976. There, he was alienated from the cold and conceptual approach to media and representation that had taken hold of most of the school — and Los Angeles — at the time, a scene which was decidedly white, male, and straight. As a queer Colombian-American artist coming into his own, Pittman instead found an unofficial home within CalArts’ Feminist Art program, established by Miriam Shapiro and Judy Chicago, where his experimentations with form and craft were encouraged. In the years after his exit from CalArts, these experiments ultimately developed into the ornate style he would hone across his career as he was working in the studio of an interior designer. As an origin story, it is a perfect introduction to the work, announcing allegiances (an engagement with craft and decoration, with queer and feminist art histories) and enmities (a rejection of conceptualist orthodoxies and dominant discourses.) Nonetheless, it fails to account for much of the specificities of the oeuvre that do not pertain to its relationship to its close or distant neighbors, specificities which were already noticeable from the very start of his career.

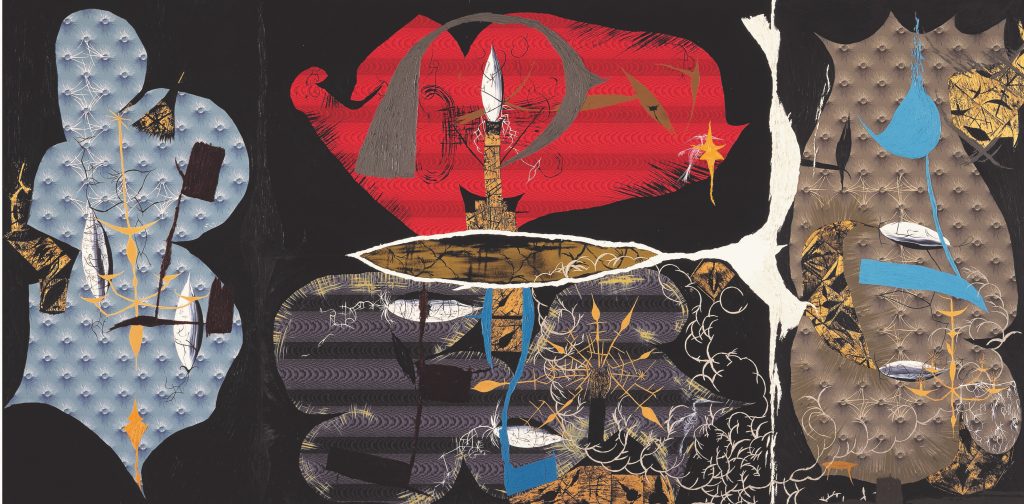

The earliest work included in the retrospective, Maladies and Treatments (1983), made seven years after his departure from CalArts, already contains many of these complexities in a somewhat larval state. A background of black paint delineates four chaotically puckered and bloated masses, each filled with a “faux” pattern belonging to the world of commercial wallpaper: light and dark outlines imitating the dimensionality of tufting or the light play of moiré. At the forefront, monochrome fields of thickly applied paint populate the painting with spindly forms, opening up into an eye-shaped tear at the center. Calligraphic elements and crosshatches grow out erratically of the wallpaper’s line-work like spiderwebs, confusing its use of three-dimensional illusions. Other elements are rendered with hints of volume and perspective, flirting with figuration without ever crossing the line: golden spindly chandeliers appear tilted; roughly shaded ivory ovals recall light bulbs, seeds, and urns. Gold leaf is applied throughout, carved through with the shadows of nearby pictorial elements. The overall effect is menacing, a stagnant void within which the supposedly clear language of modernism has been infected from the inside by half-hearted artifices. Internal tensions structure the piece: between the gestural brushwork and the inorganic shapes, between the avant-garde composition and a tradition of artificial surfaces, between the physicality of the work and its pretenses of mimicry. Between all these pairs of opposites, which are the maladies and which are the treatments is left unsaid.

Lari Pittman, Maladies and Treatments, 1983. Oil, acrylic, and gold leaf on paper, mounted on mahogany. 53 1⁄2 × 108 in. (135.9 × 274.3 cm). Collection of Tracy and Gary Mezzatesta. © Lari Pittman, courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles

While the gestural brushstrokes slowly recede from view, the sometimes ambiguously abstract, sometimes comically representative hard-edged motifs that seem to grow out of the primordial soup of Maladies and Treatments unfold throughout every other work in Pittman’s oeuvre, reinventing themselves in ever more complex configurations. In Plymouth Rock, painted only two years later, these forms have been put to work to carry a more outwardly political vision: the un-locatable abstractions of the early work have been replaced by a bleak rendition of the United States’ national project. Scrawled in an overly ornate fashion in white and cerulean, the date “c. 1620” — the year the first English Puritans arrived aboard the Mayflower — grounds the painting in an historical specificity entirely absent from Maladies and Treatments and other works of the early 1980s.

Right: Plymouth Rock. Lari Pittman: Declaration of Independence, installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, September 29, 2018–January 5, 2020. Photo: Jeff McLane

From the bottom of the canvas, rows of strié shoddily construct trees and mountains. From the top, a severe structure of black and white boxes, punctuated by the words “Love” and “Faith,” descends like a righteous and inflexible moral system. In the center, two idyllic landscapes circle one another, barely emerging, seaweed-like, out of droplets of water. Everywhere, human figures are absent, replaced only by signs of landscapes and ideologies. With Plymouth Rock, the primordial and ambiguous formal vocabulary Pittman had previously developed now illustrates America’s own creation: the dual invention of a mythical land and of the puritanical system of beliefs under which that land shall be ruled, at the genocidal expense of the people who had occupied it prior.

Ironically, this political reframing eases some of the formal tensions that agitated Pittman’s earliest work: here the artificiality of the stylized signs and the physicality of the painted surfaces work in concert, evoking the willingly naive ignorance of colonial power and the brutal violence through which it enacts its fantasies. The New Republic and Colonial Power, similarly painted in 1985, spell out this violence by inserting entrails and organs into Pitman’s dissection of American origins, inscribing the fragmented body within the imagined landscape. This violence done onto the body by and through signs is a near-constant in Pittman’s work, and one with autobiographical resonance. In 1985, the year Plymouth Rock, The New Republic and Colonial Power were painted, Pittman was shot twice in his apartment and gravely wounded in an attempted burglary.

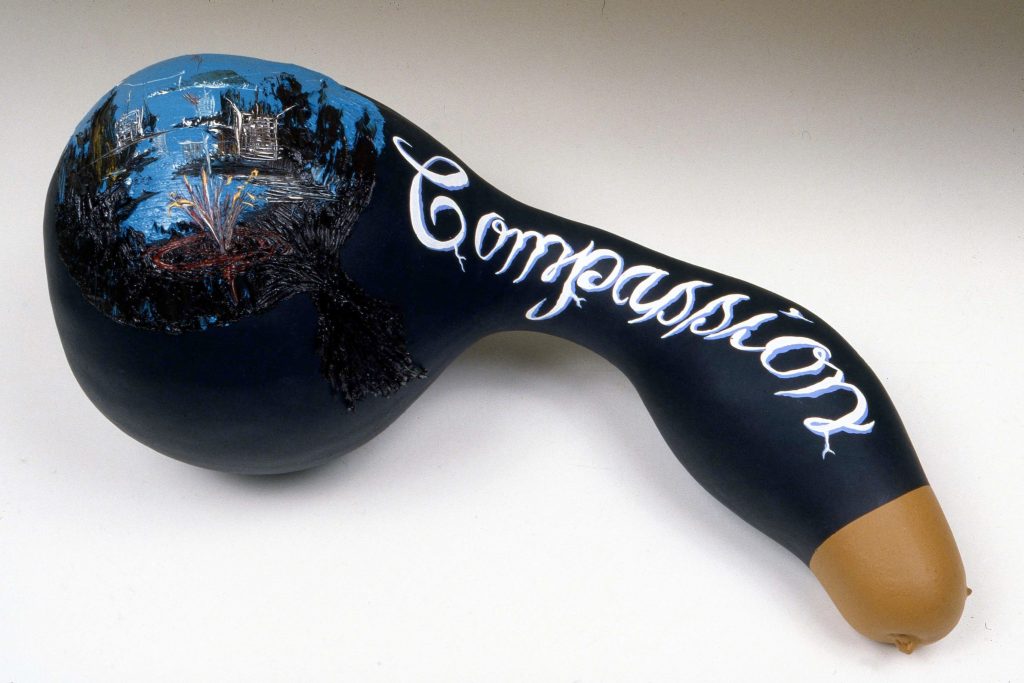

Lari Pittman, Compassion (Memento Mori), 1985. Acrylic and oil on gourd. 8 1⁄2 × 18 1⁄2 × 9 in. (21.6 × 47 × 22.9 cm). Collection of Andrew Schwartz, Los Angeles. © Lari Pittman, courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles

In an interview with the Brooklyn Rail, Pittman discusses the incident as a moment of trauma but also as an instant of clarification, consolidating his atheism and enhancing his “conjectural thinking,” a refusal of fixed answers which he contrasts with religious “conclusionary thinking.” Perhaps it is this refusal of foregone conclusions that enable him to find tenderness and subversion in the most violent settings. In 1985, Pittman also executed a series of painted dried gourds in the same style as Plymouth Rock. Each of the six gourds is painted with similar aquatic landscapes, and inscribed with a moral virtue: hope, charity, compassion, forgiveness, faith, kindness. But unlike in Plymouth Rock, the hypocrisy of the moral program is less pointed and verges on reclamation. Crucially, the painted gourd is a craft that belongs to Native populations all across the continent, and in using it Pittman conjures a possible recuperation of the language of American ideals by its victims, gesturing towards a rehabilitation of moral principles without compromising with the reality of the violence they enabled. Returning these symbols into daily life, the gourds are themselves conjectural, speculating on the possibilities for subversion and tenderness to come. Uncharacteristically for the medium, Pittman leaves the vegetables closed and untrimmed, invoking organs and bodies in gestation.

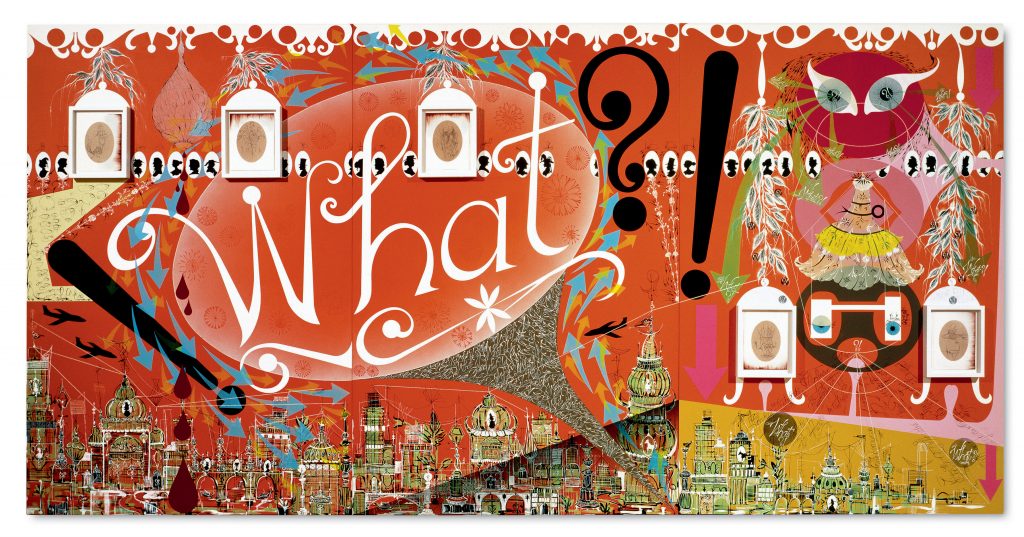

The pained emergence of this conjectural optimism in the face of violence could be the overall narrative of the retrospective — and of much of Pittman’s oeuvre. In How Sweet the Day After This and That, Deep Sleep Is Truly Welcomed, painted in 1988, the sober assessments of Plymouth Rock have been traded for joyful and panicked consternation. How Sweet the Day is enormous (96 by 192 inches), and yet filled to the brim with life and death, love and conflict. By this point, Pittman’s paintings have reached the level of complexity and detail for which they are known: the hard-edged silhouettes first explored disjointedly in Maladies have become cities, portraits, machines, organs, plants, pearls. A fantasist cityscape of fountains, domes, canals and skyscrapers conjures the artificial paradises of attraction parks and the colonial dreams of world fairs. The city, and the painting as a whole, is populated only by silhouettes: of pilgrims, of horses, of Victorian aristocrats — barely human archetypes of power trapped in a machine of light and movement that eclipses them.

Lari Pittman, How Sweet the Day After This and That, Deep Sleep Is Truly Welcomed, 1988. Acrylic, enamel, and five framed works on paper on wood. Three panels, 96 × 192 in. (243.8 × 487.7 × 5.1 cm) overall. Collection of Matthew C. and Iris Lynn Strauss, Rancho Santa Fe, California. © Lari Pittman, courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles

Surrounded by arrows, a gigantic speech bubble repeats a single word until it conquers most of the image: “What?” The indeterminate question interpellates both the viewer and the world depicted. What is this flamboyant machine inhabited only by powers as farcical as they are threatening? In the face of the textural richness of life, and of the overwhelming violence that underpins much of it, Pittman tries to hold onto both thoughts at once — the painting does not provide historical justification, no “why?” that would locate a solution in origins. Instead, the “what?” of “what is this?” but also, the “what?” of “how dare you?” and the “what” of “what is there to be done?” This dual attitude towards the object of his representation is a mainstay of Pittman’s work, and might as well be the whole attraction: to represent structures of violence and power, but also structures of desires, of pleasures, of resistance, without ever claiming to be able to entirely detangle them from one another.

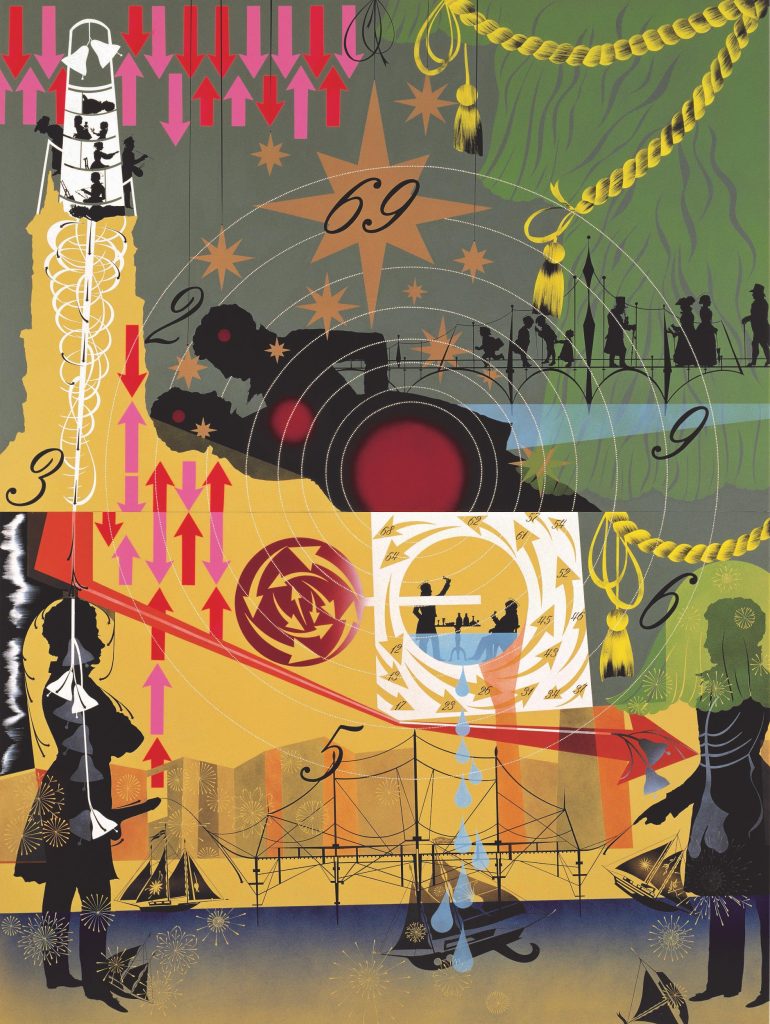

This Wholesomeness, Beloved and Despised, Continues Regardless, painted in 1990, is first and foremost a representation of the power of queer desire, and of power as it relates to queer desire. In silhouettes at the bottom of the painting, two upper class Victorian men gaze upon one another, separated by a night-blue sea filled with wrecked sailboats. A slender bridge crosses the gap between them, emerging from an erect penis and a pointed finger.

Lari Pittman, This Wholesomeness, Beloved and Despised, Continues Regardless, 1990. Acrylic and enamel on mahogany. Two panels, 128 × 96 × 2 in. (325.1 × 243.8 × 5.1 cm) overall. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by the Ansley I. Graham Trust. © Lari Pittman, courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles

The rest of the canvas is filled with movement and daily rituals: an intimate dinner is surrounded by accelerating numbers, a tower contains artists at work and children at play, the elegant bridge secreted by the star-crossed lovers is used by infants and elders for safe passage. At the center of the work, the suitors, now reunited, embrace, radiating pulses of pearls in the process. Everywhere typhoons of numbers and arrows communicate the dynamic power of a queer desire consummated: the numbers cohere in a suggestive “69,” one of Pittman’s signature motifs. The painting is undeniably celebratory, a tale of lovers creating the means for their union from their body with joyous repercussions, and yet the symbols which depict this celebration are far from universal: all of the characters are depicted as silhouettes of white aristocrats. That queer desire sometimes has to represent itself through powerful elites is of little surprise: class and racial inequalities have in large part determined which elements of queer history have been inherited or made invisible.

During the Victorian era — from which Pittman plucks out his silhouettes and some of his broader visual repertoire — leniency for homosexual conduct was the purview of almost exclusively upper-class white men. While his class status didn’t protect him from trial and imprisonment, Oscar Wilde’s writings on homosexuality have maintained such visibility in part because of his race and class; and the association of homosexuality with upper-class dandies has much to do with the erasure of working class and non-white queer narratives. Indeed, queer history is still too often represented as a history of intellectual elites, a “society of gentlemen.” When Pittman celebrates queer love through portraits of these same gentlemen, he acknowledges that most of the few symbols available to queer people to represent themselves have belonged to dominant cultures. But Pittman also finds subversive pleasure in using this language of dominance, now at least in parts quaint and distant, ironically, reframed as play — in essence, as camp. That Pittman bravely travels the thin line between these two attitudes, creating a queer language of his own through acknowledging that much of the signs available to him come from traditions of violence but also of reclamation, is much to his credit.

The series Once A Noun, Now a Verb walks the same semantic tightrope into the heart of masculinity. The first work in the series, Once A Noun, Now a Verb #1, painted in 1997 and first exhibited in Kassel for Documenta X the same year, is a tour-de-force. Mural-like in size and effect, it pictures a busy yet cohesive composition of machines and actors. Its complexities verge somewhat on overwhelming, depicting too many oddities to keep in mind all at once. Even structurally it contains multiples, framing smaller paintings within itself.

Right: Once A Noun, Now a Verb #1. Lari Pittman: Declaration of Independence, installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, September 29, 2018–January 5, 2020. Photo: Jeff McLane

As hinted by its title, the subject here is contemporary masculinity, not as a state of being, but as a performance, both conscious and unwilling. Pittman, ever the painter to take appearances seriously, goes to the end of that thought, producing a comprehensive taxonomy of performances, a composite portrait of masculinity as a churning assemblage of displays and efforts. Pale characters halfway between an egg and a sperm, symbolically both sexually undifferentiated and symbols of virility, hide their lack of definition behind a comically gendered apparatus of mustaches, wigs, hats and eyewear. Blank-faced athletes, similarly white, execute feats of strength and equilibrium in camisoles and jockstraps. Around them, the circuitry of electric power illuminating a city parallels the hidden network of sewers, toilets and piping.

Within one of the paintings-within-the-painting, bottles read “Salt,” “Pepper,” “Sugar,” “Vinegar,” “Flour,” “Ambition.” Respectively: the performativity of behaviors and accouterments; the acrobatic performances of the idealized body defining itself; the fluid efficacies of networks both visible and hidden; and, a sweet-and-sour joke, masculine performance as a sinister yet comical recipe. Amid this landscape in constant movement, delicate roses bloom with sharp thorns. This catalog of gender-as-performance is also a catalog of gender-as-power: from the psychological power of fashion to the physical power of electricity, everything in the frame is an energy that has to produce and re-enact itself to prevent its own collapse. All these mechanisms operate in parallel, each actor an object and a subject at once, an individual node powering the machine and a heroic performer attempting to navigate its trappings.

Here, Pittman’s subversive use of signs belonging to dominant languages — see for instance the muscular marble bodies of his circus performers covered in delicate silks — depicts the performance of one’s own identity as an act of power, in the most elementary sense of the term. That is to say, power as an enacting of one’s own will that is nonetheless dependent on and entangled with all previous structures and flows of power in the world. Once again, Pittman witnesses this interplay of violence and reclamation in the language of power itself, and refuses to conclude either on the inevitability or the impossibility of subversion and survival, the pleasures delivered by his own powers as a painter — enacted through virtuosity and opulence — always conspicuous as a proof of the possibilities afforded by a creative use of existing visual languages.

A Decorated Chronology of Insistence and Resignation (1992-1994), one of Pittman’s most extensive and celebrated series, makes this dynamic even plainer, juxtaposing the language of the Declaration of Independence, logos of credit card companies, street art lettering, and the vivid lights of Los Angeles to portray the bittersweet possibilities of creative resistance in an age of cooptation and diminished possibilities, all in bursts of irresistible colors and tainted pleasures.

At times, this ambivalent subversion could still prove to be too optimistic, but thankfully Pittman knows when to restrain the pleasures of his style. The Flying Carpet series, which he began in 2013, addresses directly the violence that America produces outside of its continent, a violence which American culture rarely deign to acknowledge, even less produce symbols for. Pittman structures the series around historical references to empires and their subjects — he borrows motifs and composition from 17th century Savonnerie carpets, elaborate rugs produced in the Paris Savonnerie manufactory that were favored by the court of French kings. Savonnerie carpets celebrated the power of the French crown, but were also the result of international dynamics between France and the Ottoman Empire: the technology that made them possible, the point noué, was brought back to France from Turkey by tapestry maker Pierre DuPont, in an attempt to satiate within France the blossoming market for Orientalist items by producing Ottoman-style rugs with recognizable West-European characters and landscapes. Not only were French nobles hungry for Orientalist representations that would nonetheless center them, King Henry IV of France also hoped to diminish France’s reliance on imports from the Middle East.

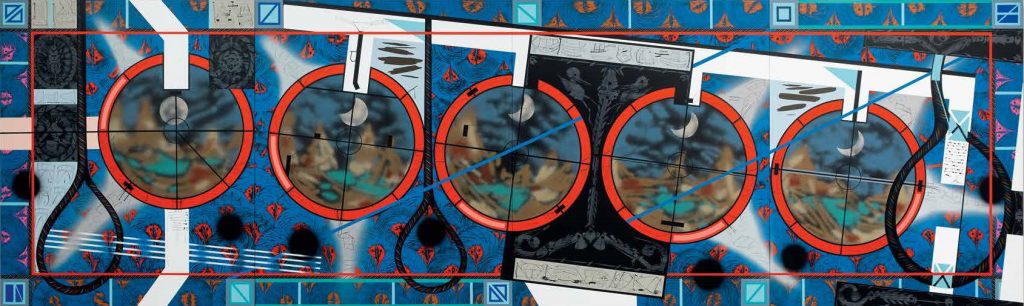

Lari Pittman, Flying Carpet with a Waning Moon Over a Violent Nation, 2013. Cel-Vinyl and spray paint on canvas over wood. 108 × 360 1⁄4 in. (274.3 × 915 cm). Collection of Maurice and Paul Marciano Art Foundation. © Lari Pittman, courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles

Pittman transforms these images of imperialist appropriation into simplified classical compositions, exhuming the harsh structures of the Savonnerie carpets by omitting their flourishes of arabesques and acanthus leaves, leaving behind only decorated borders and central medallions. Pittman replenishes these emptied vessels with symbols of present-day violence: in Flying Carpet with Waning Moon Over a Violent Nation, the decorative golden ropes of Savonnerie designs have become black nooses, framing medallions containing crosshairs hovering over blurred and deserted landscapes. In Flying Carpet with Petri Dishes for a Disturbed Nation, the medallions contain microbial cultures feeding on smudged bullets and handguns. Murderous emblems resonate within the Orientalist structures to produce a portrait of a nation devouring the content of the cultural properties of others, one able to fill them only with absences and death.

Here Pittman’s touch of subversion is not exhilarating, but uncharacteristically bleak. In Flying Carpet with Magic Mirrors for a Distorted Nation he borrows faces and poses from Mexican painter Hermenegildo Bustos, who painted bourgeois, neighbors and friends in sober yet modern portraits. Bustos had a knack for the piercing gazes and pregnant silences of local notables. In Pittman’s reimagining, none of his scarred portraits dare to meet the eyes of the viewer, perhaps in shame of the massacres that underwrite their existence. With the Flying Carpet series, Pittman explores the ways in which decorative arts carry traces and testimonials of power, both in their images — see the deployment of appropriated Orientalist motifs — and in their material histories, entangling aesthetics with international politics through transfers of production. In 1964, the French government created a second Savonnerie workshop in the city of Lodève to employ the wives of harkis, Muslim Algerians soldiers who fought alongside the French army during the Algerian war of Independence. Muslim Algerians who sided with French colonial power as a mean of survival, and were exiled as a consequence, were now offered employment in recreating the past icons of France’s long-standing imperial ambitions.

Lari Pittman’s work is historical insofar as it represents structures of power, dominant or marginalized, through the signs that they produced, while insisting on the difference between power itself and its adornments. This duality is at its most bare in the series Portraits of Textiles and Portraits of Humans, painted two years ago in 2018. These pseudo-diptychs pair portraits of historical fabrics with speculative depictions of the bourgeois individual who might have originated or worn them. For instance, Portrait of a Textile (Brocade) reinvents brocade, a luxurious silk fabric accented with gold and silver patterns floating on its surface.

Brocade’s history mirrors the history of silk trading and international power, its production moving across two millennia from China to France, from the Eastern Roman Empire to Italy. In Pittman’s hands, brocade now carries the wear-and-tear of history. Its colors are dulled, its lines sharpened, its sculptural qualities evoked menacingly by a superimposed layer of decorated hatchets. Next to it, Portrait of a Human (Pathos, Ethos, Logos, Kairos #7) is a pale figure in powder pink and tints of purple, its sleepy face constructed from striped panels sporting an elegant crown of translucent fruits. A portrait in elusiveness and fragility, with every feature both outlined and spectral, it contrasts cleanly with the hard lines and the alarming weaponry of its matching textile. “Pathos, Ethos, Logos, Kairos” are Aristotelian modes of persuasion, rhetorical strategies. But the silent figure’s only means of expression is the severe textile by its side, and the audience is left to speculate on what hidden agendas lie behind symbols of strength and domination produced by elegant but fading phantasms. Pittman seems intrigued by the relationship between the visual output of a society and its reality, and understands well that one cannot be divined from the other — to decipher cultural production, one must work through the language of persuasion with which power translates the world into images. For Pittman, in this work and in any other, being able to depict history relies on dwelling into the rhetorical core of visual languages, on working through the decorative traditions of the past to understand their producers and their audiences, exposing the mores of the present in the process.

Right: Portrait of a Human (Pathos, Ethos, Logos, Kairos #7), Portrait of a Textile (Brocade). Lari Pittman: Declaration of Independence, installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, September 29, 2018–January 5, 2020. Photo: Jeff McLane

“Decorative” has been used as a value-neutral descriptor for Pittman’s visual flourishes, as a celebration of his use of lesser-known artistic traditions, and, more often than not, as an insult directed at his practice. In a telling anecdote, Dave Hickey recalls in 1966 hearing an audience member at Pittman’s LACMA show: “[they] muttered ‘Decorative shit,’ and stalked away.” But what does the term actually imply? Pittman undoubtedly uses a plethora of motifs and compositions directly lifted from the decorative arts: a non-exhaustive list would start with his use of arabesques, scrolls, and curlicues. He adopts media associated with craft and the decorative arts, such as decorated gourds, illuminated manuscripts, gilding, and calligraphy. His choice of subjects often falls on crafted objects, ornamental textiles, and busy interiors. Even at the granular level, Pitman’s representational vocabulary continues long-standing decorative traditions. His use of hard-edged motifs, dating back from his Maladies and Treatments years and enhanced by his subsequent use of the hard and flat surfaces of Alkyd and Cel-vinyl, do at times mimic Victorian silhouettes, but belong more generally to styles of representation characteristic of decorative inlays: from pietra dura to marquetry, Pittman furthers a long functional tradition of reducing known visual elements to two dimensional shapes of solid colors, a tradition finding an unlikely contemporary deployment in the scalable world of vector graphics.

What this lengthy list of influences and inspiration lifted from the decorative arts have in common is a representational vocabulary that doesn’t attempt to imitate the truthful appearance of objects, but relies on endlessly iterated-on conventions: outlines, schematics, and patterns already part of an audience’s vocabulary of images. This is undeniably a Pop Art strategy, to represent the signs of a culture rather than its vistas, but it belongs more generally to the decorative arts: acanthus leaves and arabesques were standardized simulacra of nature long before the invention of the Coke bottle and the Campbell’s soup can. But I’d like to argue that where Pitman’s work is at its most radical with regards to his engagement with decoration is not in motifs or style, but in his conjuration of alternative modes of production and consumption.

To simplify a complex and heterogeneous history, decorative arts have been understood at least since the Renaissance as the under-recognized cousin of the fine arts, the purview of anonymous and underpaid craftsmen rather than white male geniuses. This is true for the domestic traditions associated with women’s work Pittman finds inspiration in, such as quilting or embroidery, but also for the kingly baroque embellishments he sometimes conjures. That much of the decorative arts were produced for political and economic elites doesn’t diminish the fact that their authors were often victims of power rather than executioners. Marxist sociologist Henri Lefebvre’s defense of the crafts and architectural masterpieces of feudal eras come to mind, with his admonition that one shouldn’t be “confusing the oppressors with the oppressed masses, who were nevertheless the basis and the meaning of history and past works.” As a queer Colombian-American painter, Pittman stakes out his role in a political narrative of production in inscribing himself as a continuator of these anonymous histories

Decorative arts and crafts writ large also imply modes of viewership outside of the current paradigms of the contemporary art world. Decorative objects are meant to be lived with, gazed on repetitively by owners, guests and visitors, and as such favor layers of meaning and a complexity of both content and form that can sustain repeated and long-term consideration. In that sense their temporality resembles religious objects and architecture meant for contemplation, such as domestic retablos, another of Pittman’s reoccurring inspirations. Similarly, Pittman’s paintings, with their complex surfaces of interlaced signs and their historical word play, can prove too much for a visit to the museum. Michael Ned Holte, writing in ArtForum about the retrospective, prefaces his thoughts on that other attribute often attached to Pittman’s work: “too-muchness:” “I will confess to my own weariness working through the densely installed retrospective, even over multiple visits. Each painting could take hours to decode, if one had the patience or the stamina.” In the context of an object meant to live somewhat permanently in a domestic or a social space, hours, even years of decoding are an advantage, if not a need altogether.

In his essay “Invisible Objet de l’Exposition” (the Invisible Object of the Exhibition), philosopher Jean-Paul Curnier notes that the current model of exhibition-making has transformed an ongoing relationship with art objects into a series of singular events. “From the presentation of works will emerge a singular work which is its transformation into an event under the form of the massive and visible presence of the public,” he writes. Exhibitions are a fleeting rendezvous of the public with itself, a jolt of understanding where new historical narratives are acknowledged, canons rewritten, conclusion made, and the “cultural moment” becomes legible for an instant.

As momentous as Lari Pittman’s retrospective was, Pittman’s works exceed the constraints of contemporary exhibition-making in their queer excesses, their layers of conjecture, their “decorativeness” understood in the full sense of the term. In a system where artworks are for the most part visible for months at best, and where commentary and critique has to accommodate itself to these brief instants of exposure, Pittman makes artworks that demand to be lived with. As Covid-19 upends the settled norms of art institutions across the world, such a demand might prove to be a valuable model for the institutions to come.