In his recent study on the work of Walter Benjamin and Freidrich Nietschze, James McFarland describes silence as the “herald of possibility,” suggesting that it represents not an “expressive limitation” but a “commitment to an expressionless ideal.” For McFarland, the cultivation of silence within a literary work constitutes a deliberate gesture, one intent on opening up meaning and richness within the text, rather than circumscribing possibility through exposition. Indeed, silence, in all of its indeterminacy and hermeneutic uncertainty, allows a multiplicity — with respect to narrative, interpretation, and readerly experience — to manifest within what was once a one-dimensional rhetorical space.

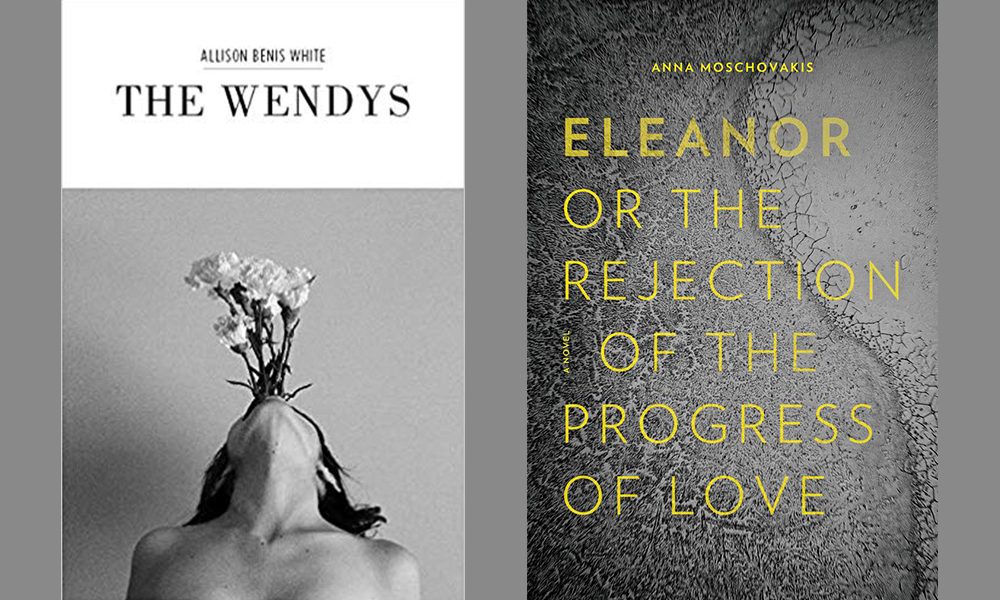

Two recent hybrid texts fully do justice to the richness and complexity that silence, in all of its myriad forms, can invite into a literary work. Allison Benis White’s The Wendys and Anna Moschovakis’s Eleanor, or, The Rejection of the Progress of Love use white space, that bright aperture, to allow multiple narratives to orbit around the same temporal moment, illuminating and complicating one another.

For Moschovakis and White, silences represent a liminal space in which the rules of storytelling no longer hold. In these brief moments of rupture, the narrative and its inevitable interpretation become entirely changeable, subject to radical revision. Indeed, White and Moschovakis share a commitment to cultivating a layered approach to storytelling, which ultimately becomes a critique of narrative cohesion and its inherent artifice.

With that in mind, their commitment to revealing the artifice — and the inevitability — of narrative comes through most visibly in the use of rupture, elision, and interruption as stylistic gestures. The swift transitions between points of view, narrative strands, and disparate versions of the same events remind us of our own expository impulses, that desire to create unity and cohesion through our participation in the text. Yet at the same time, it is these glorious apertures that allow the narrative to refract and fold back in on itself, as the same experience gives rise to a seemingly infinite array of interpretive possibilities. As White herself observes, “So many red feathers in my mind.”

¤

White’s The Wendys appears as a series of linked persona-driven poem sequences, unified only by their heroines’ first names and untimely deaths. Here, we encounter Wendy Darling, Wendy O. Williams, Wendy Given, Wendy Torrence, and Wendy Coffield, whose redacted narratives inevitably invite our imaginative work. Dedicated to the author’s late mother, Wendy, the poems also explore grief as displacement and distraction, tracking the mind’s ambulatory restlessness in the wake of tragic loss. As White’s speaker explains, “Because it is easier to miss a stranger / with your mother’s name, young and doomed.”

As the book unfolds, the apertures between sections, and between individual lines and poems, functions much like “a constellation of cigarettes in the dark,” a space for transformation. “My mind will not cool,” White warns us. Indeed, we orbit around the same moment in time, returning again and again that alluringly absent center. In doing so, we watch the speaker accumulate losses as well as their myriad narrative justifications.

White elaborates in “Zero,”

What is love but our need

to see another face?Another body, her long black

sweater still hanging

in my closet.Like the suicide note

in Japan still carved

into a tree.Something to hold

after you read.

White shows us the poem as visitation and revisitation, a loss suffered over and over again in the mind and the heart. Here, the speaker returns to the psychic space into which we were ushered in prior poems, where “your cool hand [still rests] in my hand, carved from ivory or ice.” Yet it is the space between poems that allows her to begin again and again, to layer narrative upon narrative, reminding us that the past is as multifarious in its interpretations as it is singular in its temporal boundaries. The speaker’s “need / to see another face,” then, becomes as rich in its imaginative topography as it impossible. As White herself reminds us, “…of the four truths, I remember two: we are alone, we will suffer.”

¤

Moschovakis’s Eleanor, or the Rejection of the Progress of Love, presents the reader with two distinct narrative threads, a literary text and its creation. As the work unfolds, the reader gradually realizes that writer and heroine are one and the same, that the work presents fiction as a space in which the self is seen as other, ultimately made strange by this critical distance. As Moschovakis herself observes, “Something has crossed over in me. I can’t go back.”

Throughout Eleanor, or the Rejection of the Progress of Love, it is the interruptions in the text that allow for a gratifying instability, in which perspective, storyline, and their philosophical underpinnings can suffer provocative reversals. We find ourselves shifting between text and meta-text, between product and process, and between ways of seeing the world. Consider this passage,

Halfway down the block of her lover’s apartment, she was reaching into her bag to feel for her keys. She pulled them out and held them in her fist like a weapon while the top edges of the canvas book bag, too empty with the laptop gone, flapped in the wind.

Her name is Eleanor. Did you think she didn’t have a name?

______

Or do I mean that it had come to create her? Things don’t necessarily happen in that order.

Here it is the white space, the apertures between paragraphs and sections, that allow the rules of the text, that familiar contract between reader and author, to shift without warning. Indeed, as we transition from the “laptop” and its absence, the bag “flapping in the wind,” to direct address, we are made to see that the pauses, those bright apertures, are spaces of possibility, transcendence, and change. This inherent instability allows us to see the same character, and the textual landscape that surrounds her, from myriad vantage points, among them metafictional, theoretical, academic, and deeply personal. As Moschovakis herself notes, “His lips had settled into a faraway smile, and I watched him not weep while clearly weeping in his mind. He’d never reminded me so much of Eleanor.”

¤

If meaning and narrative multiply in the space between things, how do we know which thread to trace, which one will lead out of the labyrinth of interpretive possibilities? In her experimental novel, Moschovakis states explicitly that “what I want to say is that Eleanor doesn’t know.” Indeed, choice in both of these texts seems beside the point, as it is their multifariousness that is an integral part of their meaning. This proliferation of storylines, set off by the silences between them, become a commentary on the uselessness — and the undeniable compulsion — of narrative. Yet, for White and Moschovakis, it is the bright apertures, those shining thresholds, that allow us some degree of agency in the wake of tragedy, that familiar and necessary freedom to begin again.