She smells exactly like I expected — all bubblegum and plastic and unrefined sugar. If Mallory wasn’t scrawled across her Venti-latte, I would have sworn I was sitting next to Faye Greener. It’s been nearly 70 years since Nathanael West wrote her into existence, and the wannabe-starlet has adapted to the times. She’s ditched her kitten heels for Adidas superstars and an iPhone X, adopting veganism and Pilates along the way. But it’s Faye alright, her shiny blond hair glittering like tinfoil packaging.

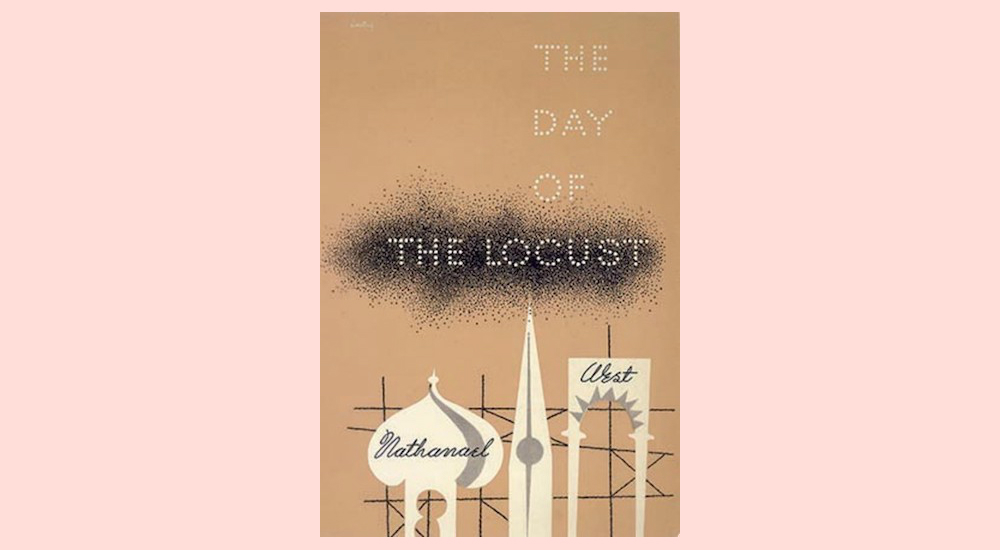

Less than a week ago, I had the profound displeasure of reading Nathanael West’s The Day of the Locust. I read it all at once, not because I couldn’t help turning the pages, but because I knew I never wanted to open it up again. It was an irritating, unsettling read, and I promptly deleted the PDF from my laptop after I finished (thank God I hadn’t splurged on the paperback). Out of sight, out of mind — or so I hoped.

Unfortunately, the self-induced amnesia didn’t take, because here she is. For the better-part of the morning, I watch Faye’s (Mallory’s) empty head bob to the beat of Fetty Wap’s “679” while she accomplishes absolutely nothing. As she stands to leave, I find myself re-downloading West’s novel. And then, impulsively, I purchase the paperback.

If you live in Los Angeles, read this book. If you can remember the last time you used Instagram, read this book. If you’ve ever worn anything from Kylie Jenner’s collection, text me your address and I’ll send you the book myself. Ten years ago, I would have described West’s novel as a warning. This — the novel seems to say — is what happens when the divide between reality and fantasy is blurred. But now, a decade later, West’s novel is less a warning and more a prescient depiction of my own self-obsessed generation. And while it’s likely too late to undo the aesthetic and moral damage inflicted by a century of Hollywood GaGa, West’s novel offers us the opportunity to be self-aware.

At its start, both the novel’s central characters, screenwriter Tod and starlet Faye, are interesting, albeit somewhat annoying. Faye is simultaneously toddler-esque and resolutely self-sufficient, while Tod is an intellectual in a city where the currency is bling, not brainpower. Neither of them fits in, and this is precisely what makes them captivating. Unfortunately, their individual charm is rapidly undermined.

As the novel progresses, Faye becomes less herself and more a product of the media-machine. She doesn’t just draw inspiration from the glossy vinyl posters that surround her, she absorbs them whole. Faye worships useless, doe-eyed heroines and convinces herself that, if she imitates them well enough, she too will make it onto the big-screen. Ironically, in becoming yet another eyelash-batting bombshell, Faye sabotages her own shot at stardom. After all, in a city of photocopied beauties, Faye’s vain, girlish charm is the only thing setting her apart. The moment that she becomes “sophisticated,” stops singing “Jeepers Creepers,” and exchanges her sundresses for nightgowns, Faye resigns herself to mediocrity.

As it was then, so it is now — many times over. But first, let’s get one thing straight: I’m not trying to victimize Mallory or any other Angeleno uber-socialite. In fact, I, along with the rest of my generation, bear an uncanny resemblance to her. Like Faye, we’ve moved beyond simply seeking fashion advice from the glitterati. With the arrival of high-resolution cameras, we’ve come to emulate them. Everyone is an Instagram-model, everyone’s life is a music-video. In hyper-obsessing over our shoes and Facebook status-updates, in posing like Bella and dancing like J-Lo, we’ve begun to lose parts of ourselves. If Faye’s fate is any indication, the sum of these little lost parts is greater than we might imagine.

If West’s commentary was relevant in 1939, it’s beyond timely now. With the skyrocketing popularity of shows like The Bachelor and YouTube’s self-proclaimed “beauty gurus,” anyone with a hairbrush and a camera can try their hand at fame. And it’s no coincidence that so many of these self-styled celebrities get their start in L.A. Fame is an Angeleno birthright, and talent is just icing on the cake. Don’t believe me? Check out YouTuber Olivia Jade, the daughter of Full House’s Lori Loughlin. Barely 17, Olivia has 1.2 million subscribers on YouTube and an invite to every party in town. And yet, rather than thanking her mother for this hand-me-down fame, Olivia describes herself as a self-made businesswoman — one who’s doing something “different.” So what does she do on YouTube that’s so original? Jade films her life — the very glamorous life of a girl whose celebrity mother married a millionaire. Is the footage interesting? Perhaps. But does it require talent, or qualify Jade as self-made? Not by a longshot.

Ultimately, West uses Faye to shed light on L.A.’s cruel consumer culture. In a city rife with ex-models and pseudo-intellectuals, success requires effective branding. And so, as Faye grows increasingly desperate for the limelight, she begins to cater to her “consumers.” Packaging is everything, and Faye learns to market herself as a projection of male fantasy. Her every behavior — every swish of the hips and turn of the waist — is designed for an audience. Why is this problematic? Because it demolishes the distinction between inherent and illusory value. What matters isn’t the content, but the sales pitch. If something doesn’t generate copious amounts of hoopla, it won’t make a profit: So no thanks, we Angelenos aren’t interested.

In the time since West’s novel was published, the nascent mass-produced, consumerist culture he satirized has consolidated. To be fair, 21st-century L.A. is one of the epicenters of LGBTQ rights, #MeToo, and other social justice movements. But too often these things take a backseat to other societal advancements — like Kylie Jenner’s hush-hush pregnancy, Rihanna’s brand-new beauty range, and Adidas’s iconic rebranding. Think I’m being dramatic? Take a look at the street-length lines preceding the launch of “dope” designer skatewear on Fairfax Avenue.

With its tawdry setting and hollow people, West’s novel possesses all the appeal of dollar-store perfume. The plot ends in a rut, the characters remain profoundly two-dimensional, and, the city burns at a movie-premiere — an ending as tasteless and overdone as L.A. itself. Reading it again, I let out a sigh. Few things are sadder than the truly monstrous.