On the walls of the woodshop at Stanville Women’s Correctional Facility hangs a prison industries catalog. Though intended as promotional material for potential buyers on the outside, the catalog is in this case advertising furniture manufactured by prisoners back to those prisoners themselves. Merchandise includes judges’ gavels, jury box seating, and witness stands: all of these are implements of an institution exceedingly familiar to those in the workshop.

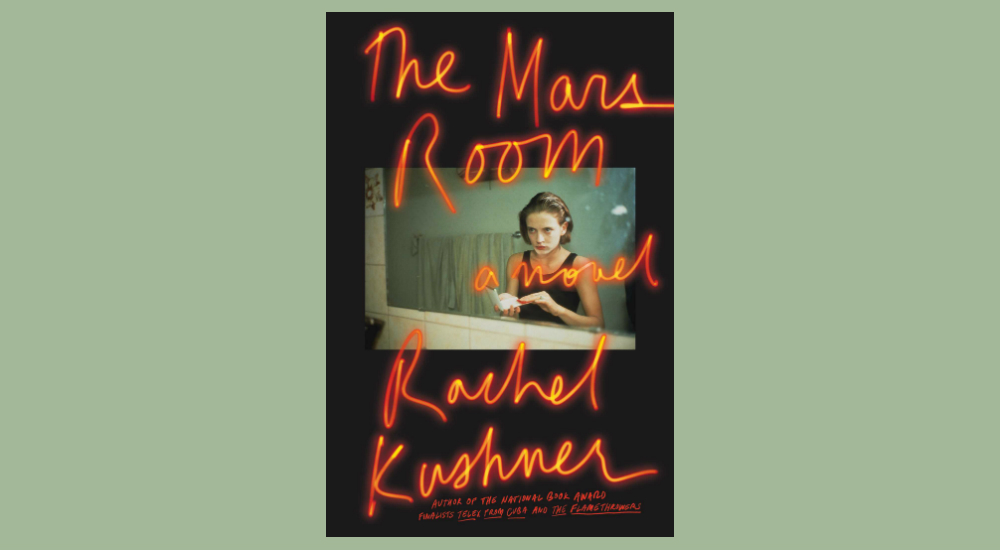

Allow me to compare this text — the brochure — to another. On the one hand, you have the set decorations of the criminal justice system reproduced on a piece of glossy paper, improbably beckoning prisoner-carpenters to purchase from their employer the fruits of their own labor, which is compensated at 22 cents an hour. This text signals a process of adjudication without once treating the consequences of that process on human lives. This text does nothing to address the contradictions inherent in its subject matter. Lastly, given what I’ve seen of the CALPIA (California Prison Industry Authority) website, I’d imagine that this text is pretty uninteresting when it comes to presentation — just plain old furniture on a white background. In all of these respects the brochure is the antithesis of the novel in which I first encountered it: Rachel Kushner’s The Mars Room is compassionate, complex, and specific.

Romy Hall is the protagonist and arch-narrator of The Mars Room. She spends her days in the woodshop at Stanville, where she is serving two life sentences without parole. Working alongside her are Sammy, Conan, and Laura Lipp — prisoners whose stories Kushner elucidates in first or close-third person alongside Romy’s. Also detailed in this book’s pages are the reflections of a self-described dirty cop who waxes nostalgic from his cell at Folsom Prison, and the labored attempts of a recent Berkeley grad to adapt to his new role as Stanville’s GED teacher. If it sounds like there’s a lot going on in this book, there is. To tell a story about incarceration in the 21st century, Kushner is a maximalist. Her narrative skitters across time, place, and perspective, between anecdotes that may not at first seem to be connected to one another. Eventually, as Kushner makes apparent the links between these digressions, an aggregate portrait of the California penal system emerges.

Kushner has a flair for detail. She treats her subjects like an expert would, with a degree of precision that suggests prolonged exposure and careful study. Her 2013 novel The Flamethrowers earned her a reputation as an authority on motorcycles, and The Mars Room adds to her title specializations in San Francisco’s Sunset and Tenderloin districts, where Romy spent her formative years. Kushner conjures a portrait of the city unlike any prior account I’ve read in fiction. Romy was a teenager in San Francisco on the eve of the first dot-com boom. The topography which exists vividly in her memory hardly aligns with what is there now. As though in response to a disbelieving contemporary reader, Romy reminds us, “A lot of worlds have existed that you can’t look up online or in any book.” She assures us that these worlds are no less real due to the fact that they are often invisible from the outside. As Kushner puts to words a San Francisco that lives large in Romy’s memory, she commits to expanding her readers’ frame of reference beyond the Googleable.

This same spirit animates Kushner’s representation of a fictionalized women’s prison in California’s Central Valley. I was not surprised to learn about the years of research that went into writing this novel; the details that furnish Kushner’s account are particular and sensory, many of them clearly mined from firsthand experience. The sundry narrators of The Mars Room are variously reportorial, nostalgic, hilarious, and anguished; despite (or perhaps because of) its heterogenous delivery, the portrait of prison life that emerges is uniquely condemning.

Where Kushner makes legible the lives of prisoners in our age of mass incarceration, she goes beyond the stale tropes often assigned to projects featuring characters who are poor, oppressed, or powerless. Certainly, readers will be galvanized when they read just how abysmally our country’s penal system delivers on its purported objectives — correction, rehabilitation, justice. But The Mars Room does more than “shine light on” a problem or “give voice to” an ignored group of people; Kushner demonstrates meaningful contingencies between the worlds that exist inside and outside of prison walls. The world which Kushner “exposes,” to use another cliché of the genre, reflects right back. Notwithstanding its remote location and fortresslike appearance, Stanville and its real-world counterparts are, in many ways, symbiotic with their environs by design. If the state-issued, prison-made judge’s gavel is one disquieting artifact that attests to the feedback loop between carceral institutions and all others, then The Mars Room is a veritable museum.