What hits you 300 pages into Red Tory: My Corbyn Chemsex Hell is how skilfully Huw Lemmey has depicted the occurrence of an irreversible shift in his protagonist’s political convictions. Having previously been a champagne socialist, as one might expect of a junior functionary in the UK Labour Party circa 2015, Tom Buckle finds he has ditched the champagne and become simply a socialist: “The more sex he had, the more distant he felt from the Party, from the centrist daddies who had been leading his hand — the closer he felt to the boys, to the binmen, to the shifting lights at night, the halos… He knew his old world had broken down; he could not go back and his Saturn was returning under a red flag.”

This is the moment Tom realizes that something novel has emerged to replace the “old world” we have witnessed crumbling for much of the narrative thus far. For months he has been attending “chemsex chillouts” — weekend-long sessions of drug-assisted group sex — which have increasingly been overflowing their putative Friday-to-Sunday confines and invading the mundane reality of the working week. The chillouts offer him an alternative social arena in which to immerse himself — a commons of fucking with strangers in place of office intrigues alongside power-hungry colleagues — but they also make him wonder if he is losing his sanity. Tom has become a regular user of a drug called MMT; the visions he has while he’s on this make it difficult to distinguish between the actual and the imagined.

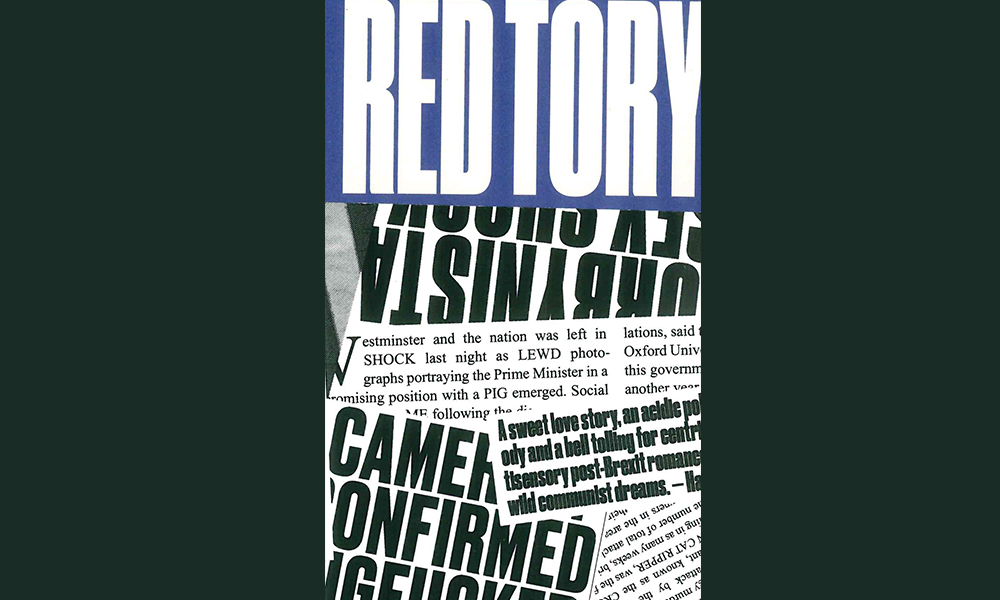

His visions are of several types. Some seem to bleed from his unconscious into current affairs (one day he hallucinates a sexual partner turning into a giant hog, and the next the newspapers are full of the then Prime Minister David Cameron fucking a pig), while in others the direction of flow is reversed. The latter type of vision almost seems to be giving him ambiguous and disturbing lessons on the genealogy of our present political settlement. For example, a chapter-length set piece sketches the chain of human connections behind cross-European drug trafficking, inscribing all of this in the margins of Empire, both the ancient Roman version and the postmodern iteration, associated with theorists such as Tiqqun and Hardt/Negri.

Yet another category of visions, generally articulated in a tone of broad humor, involves real or fantasized sexual situations being gate-crashed by Jeremy Corbyn and other figures from the Labour left. These sequences act as doubles for the waking nightmares of Tom’s Labour colleagues, who have been blindsided by the experience of a real socialist assuming leadership of a party (as Corbyn did in late 2015) that has been trying to slough off that part of its heritage for decades. The Corbyn visions don’t feel like repressed political impulses welling up from the depths, but, instead, like a mild form of psychic bullying imposed from without. (As we discover late in the book, this is not too far off the mark.) They certainly don’t seem to be the primary agent behind Tom’s political epiphany — that would be his relationship with Otto, a German anarchist.

Red Tory has a plot, which even becomes thriller-like in the closing pages, but it more often seems to resolve into concentric rings of thematic material which sometimes drift and cross. The Tom-Otto story is the innermost of these and for the most part is told in a tender, litfic-realist voice. Otto is warm and understanding, and Tom seems to become more three-dimensional the more time he spends around his lover. The two men’s encounters and estrangements create a context for Tom to act out his insecurities, project his fantasies, swing from admiration to hatred and back, take risks, retreat, change. In short, their relationship is for Tom also a type of apprenticeship premised on “[developing the] unknown worlds that remain enveloped within the beloved,” as Gilles Deleuze has written. This education ends up feeling as political in nature as it is amorous.

That Lemmey chooses to show us the whole trajectory of Tom and Otto’s love story only throws some of his other choices into relief. A number of enormously consequential historical events (not least the referendum which led eventually to Brexit) crowd into Red Tory‘s timeline, but since the book ends shortly before Trump’s election to the presidency in late 2016, Lemmey only gets to depict them in a state of what we can now see as severe incompleteness. We don’t get to see where they lead, nor what they have come to mean in 2020. Also, the book is so filled with references to real people, some of whom have all but exited the British parliamentary scene — all the way from bit-part players like Liz Kendall and Tom Watson to major ones such as former Prime Minister David Cameron and now-former Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn — that you wonder how a sufficiently comprehensive reading of the book can be pieced together several more years from now, or from the perspective of someone unfamiliar with British politics.

Maybe these things scarcely matter. Responding to events in the here and now, without excessive concern for whether subsequent developments will reveal one to have hit the target, is after all the remit of satire. But I don’t think Lemmey wants us to let him off the hook for this reason. There is something strategic about his commitment to including ephemera on the one hand and partially traced historical arcs on the other. Perhaps he means to remind us, with Gertrude Stein, that “No one is ahead of his time,” no matter how good a read we think we have on the times. Recent political history on both sides of the Atlantic has shown repeatedly that most of us do not. We are like the generals who — Stein again — “talked about the [First World] war… as a 19th century war although to be fought with 20th century weapons,” because they could not imagine what a 20th century war would look like.

Do we civilians know what 21st century war looks like, on whatever battlefield, or are we too lost in the fog of it to see? Red Tory is full of the tropes of insurrection — the “Red Falafel Thugs” with their croissant grenades, for example. These initially ask to be read as a satirical stylization of the conflict that is the focus of the book’s first half — i.e. that between the Corbynite Labour left and the Blairite Labour right — but take on a different resonance when, in the second half, it is revealed that a new front in the broader culture war perpetrated by the alt-right is underway.

The development of MMT has to do with the battle for the “psychotropic edge.” As Dr Laing, a rightwing scientist-activist explains: “the ‘psychotropic edge’ is… an attempt to recalibrate the values, experiences, outlook and ambitions of the young generation by means of new drugs. To turn drugs into a social movement that is chemically oriented towards Cultural Marxism. To literally brainwash the British, to flood out their courage, their love of their race and culture, to wash out their sense of racial pride and replace it with some sort of meaningless and relativist idea of ‘connection’ and ‘love.’” Dr Laing’s project is to develop an anti-MMT:

We have designed a plan. I have called it ‘The Albion Plan’: to infiltrate and capture the secret chemical formula the reds are using to manufacture this drug, and, with our own scientists, develop a drug of similar power and intensity. Where the Cultural Marxists use this drug to stimulate an uncontrollable political consciousness — a state of heightened awareness whereby the nature of capitalist bourgeois ideology is revealed in plain view — we will retro-engineer the drug to a new state, one in which a healthy fear and paranoia of difference is cultivated, drawing the user back to their own kind, nurturing within them a natural sense of family, defence, prosperity, kinship. Just as addictive, but the high will be so much more potent… Instead of brainless, open-armed refugee lovers, we will chemically restore the natural family balance, and in turn create great hallucinogenic visions of the pure ethno-state!

This reveal makes clear that the first half of Red Tory is a smokescreen; the message is that what really matters for a 21st century British socialist is not staking it all on a written-in-water conflict between opposing wings of the same social-democratic party, but (to paraphrase Otto) believing in those people who are trying to kill you.

It is probably true that, with Tom, we are only able to glimpse the broader picture by increments, otherwise the contrast with our comforting illusions would be too jarring. But in the UK the left didn’t make the adjustment in time. The Labour party continued to be mired in internal feuds until its catastrophic defeat in the December 2019 general election, and entirely failed to grasp how comprehensively it had been outflanked by Boris Johnson’s Tories with their simple offer to “Get Brexit Done.” If anti-MMT were made into pills, those three words would probably be stamped on them.