The South Side Weekly recently lamented “a decades-old journalistic approach that sees most of Chicago as nothing more than a poverty mill or battleground, a place ripe for sentimentalism and scolding but never appreciation.” Throughout its history, observers from inside and out have projected sweeping ideas onto Chicago: the city has a quality that invites naming, from “Mud City” to the “Promised Land.”

The Art Institute of Chicago’s “Never a Lovely So Real,” an exhibition of Chicago photography and film from 1950-1980, takes its title from one such attempt at naming. Writing about the city in 1951, Nelson Algren mused, “Like loving a woman with a broken nose, you may well find lovelier lovelies. But never a lovely so real.”

The Art Institute’s exhibition takes a close look at Chicago’s broken nose, and at its brilliance. In Don Klugman’s film Nightsong, the forgotten Black folksinger Willie Wright croons achingly to an indifferent crowd of white couples in a nightclub. In an untitled Doug Ischar photograph from 1985, two men hold one another carefully, almost tentatively; the print comes from his series “Marginal Waters” documenting the Belmont Rocks gay urban beach amidst the AIDS crisis.

From Gordon Parks’s photographs of Metropolitan Missionary Baptist Church to Danny Lyon’s images of new Appalachian immigrants in Uptown, “Never a Lovely So Real” presents communities marred by segregation, alienation, and the ghost of industry. But the photographed subjects stand carved in relief from their battered city: they build communal life underground and in plain sight, in makeshift dance clubs, grand churches, and subversive political organizations.

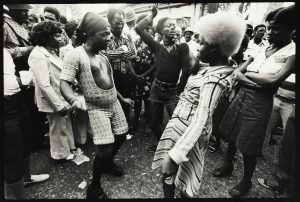

The exhibition’s major rooms consider Chicago as an African-American cultural nerve center, looking at the city through the eyes of the great imagemakers who preceded, birthed, and were influenced by the Black Arts Movement. These include series ranging from Gordon Parks’s photographs of the ministry and defense training of the Nation of Islam, to Valeria “Mikki” Ferrill’s electric photographs of the Garage, an improvised club on East 50th Street that hosted weekly DJ battles and jazz music on Sundays.

In the exhibition’s entrance room, Kenji Kanesaka’s 16mm short film Super Up plays on a hump-backed monitor. Super Up is a glittering, haywire dream about Chicago. Some of its images and sounds are fleeting, while others return frequently, creating a world governed by impression rather than time. While the camera pans over the faces of several anonymous women talking in phone booths, one woman’s invasive grimace returns over and over again. The chug of a freight train pulling dozens of impotent cars along a track cuts through the film at will.

From this world, a story emerges about a young African-American boy. When a white woman reaches her fingers to remove a cigarette from his mouth and replaces it with a Pepsi, he steals a bottle of milk from her. Later, he is haunted by a sexual fantasy in a grocery store. Eventually, the bottle of milk comes crashing down in a rich splatter. In Kanesaka’s film, commerce and sex are so close together as to become indistinguishable from one another. The two forces create a world so saturated with corruption that it needs to be undone completely, and then triumphed over.

While Kanesaka signals that Super Up is told through the eyes of a boy from Chicago — he begins his film with a shot of the protagonist’s probing eyes — the film is clearly the vision of an outsider looking in. Kanesaka’s film approaches Chicago with preconceived notions of the city as an American symbol with easily identified visual features. Advertisements, mannequins, and politicians make up this landscape — they are spliced and contorted, but they come up short, bland and overused. Kanesaka’s imagery is not particular to the experience of any one locality or community in Chicago.

Without dialogue, Super Up uses symbols as its language. Kanesaka’s film is an allegory about the toxic impact that American consumerism has on the young, impressionable, and disenfranchised. However, Kanesaka seems able to imagine the experience of a young Black boy in Chicago only in a dreamlike world, not in the real one.

“Never a Lovely So Real” sometimes falters in putting images and stories into context. It’s confusing, for example, to find a film by Kanesaka — a Japanese filmmaker — in a room of work made mostly by Chicagoans. Many of the works adjacent to Super Up have a palpable specificity that lends them authenticity. Super Up is just as riveting as the images that surround it, but Kanesaka’s work inhabits a dream, while the other works inhabit Chicago.

In general, the exhibition loses steam when it turns away from the glow of the Black Arts Movement to images of other communities in Chicago. Though an early short from Kartemquin Films about the impact of a Depaul University expansion in Lincoln Park is particularly wonderful, as is much of the later photography in the outer rooms, the exhibition’s focus is blurred as it chugs on.

Speaking of her subjects at the Garage dance club, Valeria “Mikki” Ferrill said, “I covered the walls of the Garage with pictures of themselves.” In the Garage, Ferrill’s subjects saw themselves on the walls, photographed by a fellow attendee. While they danced, took a seat, and eyed someone beloved, they also saw themselves reflected in images gliding past them. Like Ferrill’s subjects, visitors to the Art Institute exhibition are surrounded by imagined ideas about Chicago. But only some of these ideas are grounded, forged by Chicagoans in their daily lives and sent into the world as gifts. These are the ones that visitors feel in their bones.