In Black Sun, Julia Kristeva observes that mourning is, in essence, a loss of language. Words abandon their meaning; sentences no longer fit together the way they should. Yet it is language that allows us to derive significance from an experience, integrating it into our understanding of the world around us. The sorrow of a lost object, then, is a double loss: the thing itself has vanished and so too has its place in the lovely arc of story. Once we have fallen out of language, the absence itself becomes unspeakable, and likewise, the stories that makes us ourselves.

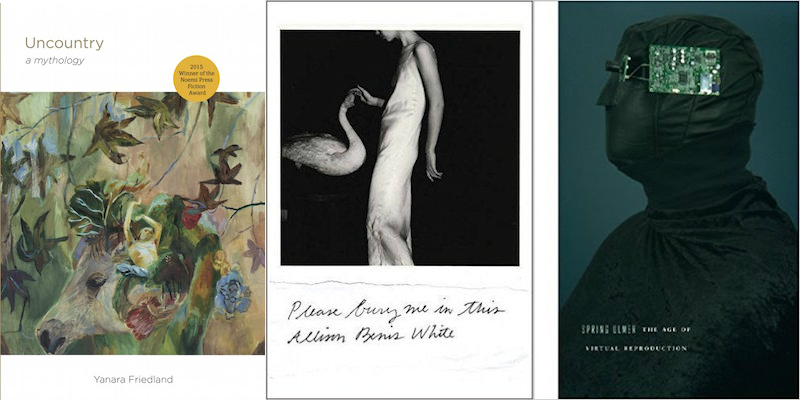

Three recent hybrid texts explore, with subtlety and grace, this troubled relationship between grief and the various structures of meaning-making that we have inherited: grammar, narrative, their implied causalities, and their inherent limitations when faced with misfortune. We attempt to impose the logic of story, the clean reasoning of the sentence, when there is no satisfying causal relationship to be found. Allison Benis White’s Please Bury Me in This, Yanara Friedland’s Uncountry: A Mythology, and Spring Ulmer’s The Age of Virtual Reproduction offer a provocative disconnect between their pristine prose paragraphs and the fitting fragmentation of meaning found within them. We are reminded of what it is to be rendered “wordless,” with only the “thin clothes” of narrative to cover our grief.

In the work of White, Friedland, and Ulmer, we are made to witness language as it reaches for something that lies just beyond its boundaries. Here, we are offered “glass beads” and “paper houses,” “swans” and “paintings of windows” that orbit around an alluringly absent center. The reader is subtly and skillfully implicated in their desire for the story as memento, as “silver, gleaming” keepsake. Yet as sentences begin to assemble themselves in fits and starts, the speakers of these gorgeously fractured poems are left only with “words, their spectacular lack.”

¤

White’s Please Bury Me in This takes the form of prose epistles, in which the terms of address are constantly shifting. In many ways, the book’s dedication is key to understanding a provocatively destabilized variation on the lyric: for the four women I knew who took their lives within a year / for my father. The speaker’s grief uncenters her. Voice is revealed as a social construct, predicated on the existence of relationships; without the presence of the other, one struggles to speak. “I want to tell you something memorable,” White writes, “something you could wear around your neck.” Yet this stunning collection does much more, confronting instead the philosophical problems inherent in our desire to memorialize the lost other in language.

As the speaker drifts between remembered scenes, rooms, and objects, the work’s neatly constructed prose stanzas prove deceptive, yet purposefully so. For the reader, prose evokes a variety of readerly expectations: unity of voice, consistency of address, and a readily apparent narrative arc. We have been trained to expect artifice: the “a string of glass beads wrapped several times around” the heroine’s neck, “a napkin folded into a swan,” then “yet another beautiful thing.” Approached with that in mind, the work’s fractured, ambulatory structure surprises and delights with its verisimilitude, especially when considering the actual workings of the mind when engulfed by grief:

And years later, deliriously, when he was dying, Do you have the blood flower?

I was taught to chant ‘he loves me, he loves me not’ as I tore off each petal in my room.

You are not alone in your feeling of aloneness. Yes, I have the blood flower.

White, fittingly and deftly, offers only the illusion of wholeness. Certainly the prose in this passage appears in cleanly reasoned sentences, each subject-verb-object construction implying its own discrete causal chain. Yet within this seemingly linear, seemingly rational structure, White skillfully and provocatively fractures time. The “torn petals” and innocent “chant” of the speaker’s childhood are held in the mind alongside her later efforts to reach beyond the scope of language and voice: You are not alone… This fragmentation of time and narrative, and the layering of discrete temporal moments, calls attention to the artifice of the various frameworks we attempt to impose upon experience. These often linear, often causal ways of creating order from disparate perceptions ultimately fall short of accounting for the ontological violence to which we are all subjected, inevitably. For White, what is truly meaningful resides in the aperture between two words, the threshold between rooms in “the museum of light.”

¤

Spring Ulmer’s The Age of Virtual Reproduction engages similar questions of language and grief, albeit on a larger scale. The work offers a provocative and timely exploration of cultural memory and shared consciousness in the digital age, prompting the reader to consider the changing nature of mourning in a technologized social landscape. Carefully and convincingly grounded in the writings of Walter Benjamin, August Sander, and John Berger, Ulmer’s work provocatively resists the language and structures of theory, seeking instead to create a more personal lexicon for sorrow and the visible fragmentation of culture and community.

Wonderfully associative in their logic and narrative progression, the linked essays in this collection depict the “fire” and “bullet-shattered glass” of shared mourning while refusing the impulse to weave a master narrative. In many ways, Ulmer’s subtle protest, her linguistic resistance, comes across most visibly in the moments of rupture between neatly constructed, seemingly well-reasoned, sentences. Much like White, Ulmer upholds the importance of silence, and the space between words, for deriving meaning from the “played tricks” and “moral…anesthesia” that surround us.

She writes in “Peasants”:

They wear suits. Someone once remarked that they do not seem to fit them — their bodies cannot be tailored. I find their unfitted wear beseeching. I want them in these ill-fitting suits, enjoying their outing, looking so ephemeral. It is as if they never stopped for a picture. History cannot remember their names, just their bodies…

As in many passages in The Age of Virtual Reproduction, Ulmer’s narrator mourns the once clear path to an ethical life. Here the photo, and the perceived innocence of the individuals in “ill-fitting suits,” belies the speaker’s nostalgia for what she perceived as a less conflicted social landscape. What’s perhaps most telling, though, is the rupture between each sentence, the sudden leap from one idea to the next. Though longing for a beautiful past, in which everyone seems at once “beseeching” and charmingly vulnerable, the speaker has clearly internalized the values of the digital age. To move from the suits in the photo to the shortcomings of the human body (which “cannot be tailored”) implies a hierarchy, privileging the made thing, the consumer good, over what is human. Ulmer’s swift transitions, subtly and powerfully, implicate her own narrator, suggesting that these values no longer warrant justification. In this way, Ulmer’s cultural critique, her grief when faced with cultural and political loss, is rendered all the more powerful by the style of her writing. What has been mislaid, for Ulmer, is an ethical sensibility, a moral narrative that once populated the space between actions, the pause between two words.

¤

Much like White and Ulmer, Friedland calls our attention to what’s left unsaid, and what cannot be said, in a narrative. Uncountry: A Mythology is presented as a series of self-contained flash fictions, which document, in luminous and lyrical fragments, a history of political exile. Often drifting between biblical narratives and 20th century politics, Friedland offers a model of time and history that is circular and elliptical. We are pulled again and again towards the same sorrow, a grief that is deeply rooted in a shared cultural memory.

As Uncountry progresses, we are made to see that the grief accompanying a lost political struggle, the grief of nationhood, is greater than the individual that bears it. It is a “dark chamber,” a “sea” that is constantly widening within the individual psyche. Friedland writes, for example, in “History of Breath”:

Above the fireplace, which is never lit, his face during wartime. Full uniform, legs crossed, face in half profile against a wall of windows. On the table next to him a plant, cup saucer, a hunched angel in bronze…

What’s perhaps most telling about this passage is its purposeful ambiguity. We are presented with archetypes of a mythic quality — the “half profile” of the soldier in “full uniform, legs crossed,” the “hunched angel in bronze.” In much the same way that Friedland forgoes specificity in description, so too the narrative drifts between wars and exiles, which slowly accumulate, one superimposed over the other. In many ways, it is this refusal of singularity that is one of the most powerful techniques that Friedland has at her disposal. By unsaying the particular, and denying the purported uniqueness of each sorrow, she gestures toward the presence of a larger cultural machine, which ceaselessly replicates archetypes, myths, mistakes. Much like White’s gorgeously elusive prose, and Ulmer’s wild associative leaps, Friedland’s stately and mythic micro-narratives are perhaps most powerful in their silences. She reminds us to examine the space between words, the ethical implications of all what cannot, and will not, be said.

¤

If mourning is a loss of language and narrative, perhaps that silence can be brought to bear on its own provocation. In the work of White, Ulmer, and Friedland, mourning, and its accompanying quiet, is no longer a passive endeavor. Rather, one’s alienation from language, its implied order and structure, becomes pure possibility, a source of transformation, wonder and insight.

These three collections show us that silence can be made to speak on behalf of the lost other, perhaps even more powerfully than the familiar and ready-made structures of narrative. In each book, we are made to witness the underlying logic and assumptions of language as they are unsaid, and in this unsaying, we see them, suddenly, finally, and irrevocably, anew.