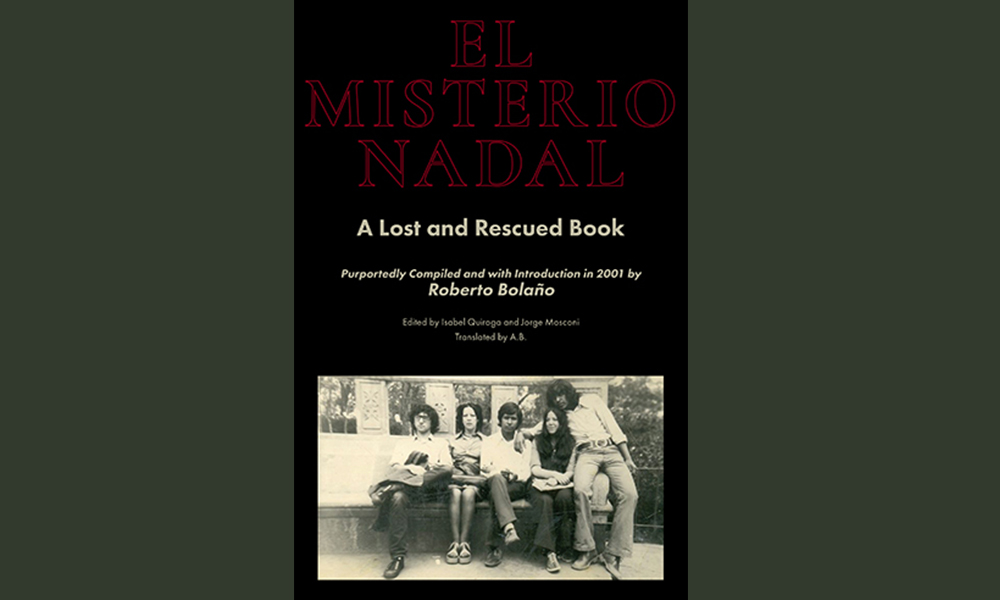

My copy of El Misterio Nadal reached me by post, inscribed with a “best wishes” and signed “A.B.” A few weeks earlier, while corresponding with me about new translations and poems to post on the mad-bad-and-dangerous-to-know Dispatches from the Poetry Wars website, poet-translator Kent Johnson had asked whether I’d like to read this strange book, which he had helped facilitate in publishing. Why not? After all, it purportedly included texts by Roberto Bolaño. But what awaited me was much more: a delightful hall of mirrors, or dead-end paths and shadows, sudden atriums flooded with light, then more mazes… Have I found my way out yet? No. Has it been worth it? Without a doubt. I entered without Ariadne and ball of string, without even a flashlight. I hope these notes on the book will help readers, or at least whet their appetites.

Perhaps a distant inspiration — even unbeknownst to the mysterious sources of this book — is the The Aspern Papers by Henry James. There is the same air of intrigue and investigation, as well as obsession. The book celebrates not only the work of Bolaño, but of a whole literary culture rooted in Latin American Modernismo, Anglo-American Modernism, and Surrealism. It is a culture I share with other poets, like Kent Johnson, and which involves lengthy e-mails and conversations about hidden voices like Carlos Martínez Rivas, Joaquín Pasos, Antonio Gamero… Like Pale Fire or Hopscotch, this “Lost and Rescued Book,” as its subtitle describes it, closes with an appendix of disposable chapters, fragments that gather a narrative frame of their own, leaving the reader with perhaps the fifth or sixth book within a book within a book (to describe the novel’s architecture). In that closing section, one discovers Bolaño’s preference for Kent cigarettes and his talent in the kitchen — “very good paella” — not to mention the Thermidorean Reaction, the White Terror, Monarchiens and Girondists, Mensheviks, Kadets, poets with oddly Slavic-sounding names like Amado Nervoski and Dickinsonova, as well as Bourgeois Revolutionary Estridentista Poetry.

El Misterio Nadal focuses intensely on the essential Surrealist poet Benjamin Péret, the only one who never abandoned the movement, nor ever experienced the wrath of André Breton and expulsion inflicted by that explorer of life as taking place elsewhere. Starting with an appreciation by Roberto Bolaño — again, one takes this as a real text, or “real” in the Nabokovian sense — of Péret and comments on previously unpublished texts and transcriptions, the section continues with many voices converging and departing down separate paths in the labyrinth. Why Péret? It’s important to recall his initially uneasy friendship with Octavio Paz. Exiled in Mexico during World War II, the Frenchman was in close social contact with Paz — the darling boy of government grants, the official voice of Mexican culture — yet Péret was never one to mince words. He dismissed most Mexican poetry, and criticized the country’s cultural life as being excessively self-involved, and when he was chided by Paz, Péret coolly responded that Paz only sought admiration, and anything else was perceived by him to be an insult.

Paz, perhaps like current poets and writers favored by the State’s cultural apparatus, professed great admiration for poets and thinkers who were marginal, outcasts, or trailblazers of new visions, hence his numerous texts on Surrealism, Luis Cernuda, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, and others. His poetry may be more risk-taking than the well-chiseled reveries of the countrymen who proceeded him, like Jaime Torres Bodet or Enrique González Martínez, yet Paz seemed always to seek a pluralism at the same time as he sought a centrist position, be it politically — decidedly left of center by North American standards, yet ultra-right in the view of many Latin Americans — or in his work. One long poem in particular, though, Piedra de sol, miraculously captures the Pre-Colombian Mexico that fascinated Péret, along with such literary appurtenances as Melusina, l’amour fou, Heloise and Abelard, and the Spanish Civil War. The exchanges between Péret and Paz cumulated into lasting friendship, and in 1959, Péret’s French translation of Piedra de sol was published, although sans the prologue promised by Bréton.

Knowing of Bolaño’s caustic take on Mexican poetry and poets, it’s no wonder that Péret receives so much space. Just as importantly, the transcription of a translation of the interrogations of Péret by the Police Intelligence Division of Brazil, followed by the “Cultural Attaché” of the Embassy of France in Brazil, introduces Brazilian letters into the book, and also contains some of the most wild and delightful passages on Surrealism itself, with none other than “Péret” explaining the movement to detective thugs, in a prose that flows magically with “giant mollusks and driftwood,” “fat ladies with clouds for derrieres,” “slogan-yelling trees,” “paths of wonder,” and the “marvelous” that can never be comprehended by “brains of wood.” The energy in these pages seems to tap into the best prose by Gérard de Nerval or the visions in Théophile Gautier’s Le Club des Hachichins, not to mention Breton and his Soluble Fish.

The longest “Bolaño” text is an autobiographical chronicle about his friendship with the mysterious Nadal, setting up the rest of the book with references to translations of the two interrogations involving Perét, as well as of Péret’s poetry. This chronicle is followed by a multiplicity of translators and editors playing a type of “hot potato” game, so that even the careful reader is unable to pin down just who is responsible for this… found text? assemblage of fictional fiction? One thing is for sure: the assembler of this book is a well-weathered explorer of Latin American poetry. Apart from documenting Péret’s appearance in 1940s Mexico and Brazil, El Misterio Nadal includes wonderful pages on two of Latin America’s most original and least known poets: Carlos Oquendo de Amat (Peru, 1905-1936), recognized for his sole collection of fold-out poetry, 5 Meters (1926), and Omar Cáceres (Chile, 1905-1936), another poet with a single and legendary volume, Defense of the Idol (1934). The passages pertaining to those poets include letters addressing Eliot and e.e. cummings. Real correspondence? That’s all part of the fun. Without a doubt, El Misterio Nadal is a must read for students of Latin American literature, as well as Iberian letters. And while connecting this book to The Aspern Papers may seem a stretch to some, the Quixote’s metafiction is undoubtedly the gushing spring from which this volume flows.

This eccentric and wildly unique tome holds many delights for the enthusiast of Mexican, Chilean, and Argentine poetry; Surrealism; detective fiction; explanatory notes and scholarly asides like those that crowd the fictions of Borges and Nabokov; apocryphal writers and masks; Marxism and political trends in Latin America; “translations” like Kenneth Koch’s versions of South American poets; and the effluvium of voices, genres, deserts, jungles, and cities of the imagination. The very sui generis nature of El Misterio Nadal may make the book resistant to traditional reviews and appraisals, yet like other titles in the estuary between genres, it will come as a thrilling relief for readers yawning at the usual suite of MFA-endorsed poetry and prose. Its narration is unreliable, but it is certain to be a reliable source of wonder.