At the outset of The China Hustle (2018), Dan David proclaims, ominously, “There are no good guys in this story, including me.” But David, co-founder of the hedge fund GeoInvesting, is undeniably the film’s protagonist. It follows him from Geo’s offices in Skippack, Pennsylvania through due diligence investigations in mainland China, his unsuccessful attempt to lobby congress to investigate the fraud he claims to find there, and an international whistleblower tour. In the interim, David also makes time to visit to his childhood home in Flint, Michigan, so that filmmaker Jed Rothstein can appropriate the associations with exploitative globalization popularized by that city’s more-famous scion, Michael Moore. At a humble back-patio cookout, David, corn in his teeth, explains reverse mergers to a crowd of earnest, elderly Midwesterners, one of whom swoons, “You’re a good man, Dan!” — effectively negating David’s earlier protestations to the contrary.

In January, Dan David (predictably) declared himself a congressional candidate. Whether or not Rothstein and executive producer Alex Gibney knew of David’s political aspirations during filming, their documentary became, upon its release in March, a de facto publicity reel for yet another millionaire on the campaign trail. Gibney’s production company, responsible for incisive films about corporate fraud, income inequality, resource theft, graft, and the military industrial complex, became an unlikely checkpoint on the hedge-fund-to-House-Republican pipeline.

Dan David is a self-described “activist investor.” This euphemism was invented by Yale economists in the early 1970s to describe what were then better known as “corporate raiders,” private investors who used the threat of hostile takeover to “greenmail” executives into either buying back stock at a premium or gutting the company to goose its share price. The Yalies who authored The Ethical Investor (1972) postulated that this tactic, though typically pursued only by unsavory greedheads, could be appropriated by well-intentioned institutions, including Yale itself, to pressure companies into smarter and more socially conscious business practices. Of course, what mainly happened thereafter was that the unsavory greedheads started calling themselves “activist investors” and institutions like Yale became less prejudiced against corporate raiding. And Gordon Gekko giggled gleefully.

Until recently, “activist investing” still implied taking an ownership stake, at least in the short term, with the intent of leveraging those shares to manipulate management. Many economists and financial journalists still insist on using the term as though it refers exclusively to this tactic. Joe Nocera, for instance, treats activist investing as the antithesis of short-selling in his recent defense of the latter. But Dan David declares himself both a proud activist investor and an unrepentant short-seller, revealing the extent to which the parlance has evolved. While the narrative Nocera prefers, of manic bulls facing down cynical bears, is an enduring Wall St. fable, one which China Hustle also plays to great effect, the truth is that bulls and bears co-exist, not only in the same firms, but in the same persons, many of whom now prefer to brand themselves activists. Piling up proxies and publicizing short positions are the double sixes of cowboy capitalism, wielded ambidextrously by many contemporary sharps.

Both Nocera and Rothstein posit that short-sellers are the pariahs of high finance, operating at the fringes because the traditional Wall Street firms “tend to take the self-interested view that short selling is the scourge of capitalism.” This righteous posture — the unfairly maligned short-seller battling deceptive and dimwitted corporate titans — is neither unprecedented nor unpopular. Bill Ackman, David Einhorn, and Steve Eisman, among others, painted themselves as unfairly persecuted blue-collar vigilantes, even as they were enriching themselves from the destabilization of the global economy in 2007-2008. David delivers a similarly deft performance in China Hustle, admitting, as if surprised by his own altruism, that if he succeeds in preventing reverse merger fraud, he will have deprived himself and his fund of their primary profit center. Poor King Midas. What a blessed public servant he will surely make.

The glorification of the short is one of the most surprising cultural paradoxes of the post-crisis decade. The successful self-promotion of Einhorn and his ilk certainly has something to do with this, as do the tone-deaf rants of executives like Lehman Brothers CEO, Dick Fuld, who famously proclaimed that he not only wanted to “squeeze those shorts,” but “reach in, rip out their heart, and eat it before they die.” China Hustle, of course, dredges up this footage, thus making the most persistently unpopular scapegoat of the subprime crisis into a strawman for Dan David, SuperShort, to pummel.

For the past decade, despite relatively widespread contempt for finance generally, activist investors have consistently benefitted from inexplicably generous mass media characterizations. China Hustle, though it may propel Dan David to electoral victory, is like a dustmite riding the coattails of Michael Lewis’s bestseller-turned-box-office-smash, The Big Short (2010). It’s hard to overstate how influential the The Big Short has been on public understanding of the subprime crisis.

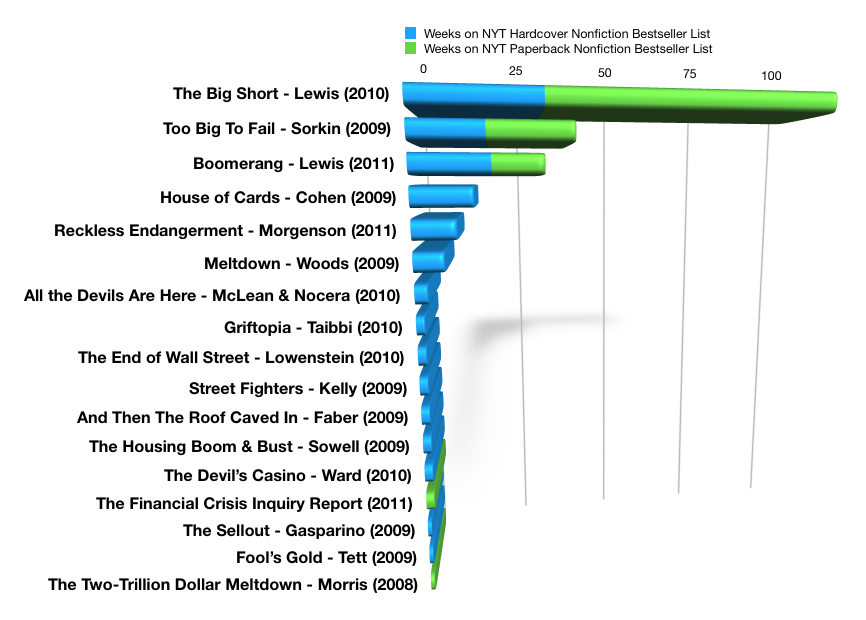

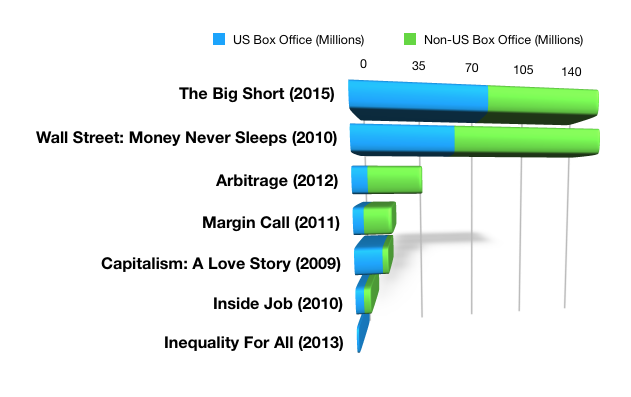

As you can see from the above graphs, both the book and film versions of The Big Short, at least in terms of their measurable popularity, dwarfed every popular postmortem of the subprime crisis, even other perceived “smashes” like Andrew Ross Sorkin’s Too Big To Fail (2009) and Charles Ferguson’s Inside Job (2010).[1]

There is a significant irony in The Big Short becoming the dominant narrative of financial meltdown. Lewis self-consciously designed it to be a counter-narrative. The first wave of crisis chroniclers, Sorkin foremost among them, focused almost exclusively on the losers: the bankers at Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns, the bumbling Bush Administration, the duped and delinquent borrowers, the middle class taxpayers. These chroniclers were primarily Wall Street beat reporters who covered the unraveling daily from 2007 to 2009 and were looking to cash in on their proximity to this epochal event. But Lewis, whose books had already sold, as he put it, “not John Grisham millions, but millions,” never conceived of this as a career-making story. He had no incentive to be first, and thus published The Big Short many months after most of the “competing” books listed above. The story of the losers had, by this point, been thoroughly told. His niche, and he saw it as exactly that, was going to be tracking down the much less visible winners.[2]

He treated the “shorts” as pretty sympathetic characters. They further benefitted from being played by the likes of Christian Bale, Steve Carell, Ryan Gosling, and Brad Pitt in the Oscar-winning Adam McKay adaptation. MacNeil/Lehrer’s Jeffrey Brown, evidently affronted by Lewis’s romantic portrayal, said, “The heroes of your book, they’re not heroes […] They make a lot of money betting against these institutions, but essentially betting against the US economy.” Jon Stewart put it a little more bluntly: “It seems like we should not have a financial system where you could profit cheering for its demise […] You know, I play craps sometimes. And there’s always a guy betting against the table. And that guy is usually a dick.”

Lewis drank the activist investor Kool-Aid, which was perhaps inevitable given the reflexive relationship between an author and his subject. But when his revisionist history painting these opportunistic “dicks” as “complicated heroes” became the standard account, it served mainly to recapitulate the delusions of rational markets and meritocratic compensation which Lewis has, to his credit, often railed against. The “masters of the universe” have merely moved from seersucker-and-skyscraper investment banks to office-park-and-hundred-dollar-hoody hedge funds. The broader implications of applying their so-called genius to siphoning large portions of fictive capital from the tax-sheltered digital casino that sits atop the global economy remains unchallenged. As it became increasingly impossible to admire the rich guys at Goldman Sachs and Wells Fargo, Lewis merely offered up an alternative set of rich guys to admire.

The truth is, the fraud is everywhere, including amongst the “complicated heroes” of the activist investment world. Take, for example, this completely hypothetical and hyperbolic example:

An activist investor — let’s call him, say, Bobby Axelrod — sets his sight on a small mining company — say, Independence Mines (IPM) — which has tapped out its domestic sites and is now predominantly operational overseas in, like, we’ll call it Rhodesia. So, Axe wants to short IPM. This would once have required finding a broker from whom to borrow shares. Perhaps he finds one, but, just for argument’s sake, let’s imagine there’s not much readily available IPM stock to speculate with, perhaps because much of it is held by employees. No problem, Axe can worry about this piece later (or maybe not at all) because he can buy put options without actually possessing any IPM shares. He’s basically just promising to possess them at a future date.

Now, because this is a hypothetical and I’m a literature professor who understands the construction of this fiction better than the math that’s required to make it profitable, we’ll use some nice round numbers. Let’s say there are 1,000 shares of Independence Mines stock in circulation and they’re trading at $100 per share on April 1st, when Axe negotiates his put option. He promises that by the end of the month he will sell 100 shares of IPM stock to his counterparty, we’ll call them Layman Brothers, for $50 a share. Axe has one month to cut Independence’s stock price in half, just to break even. He books a trip to Rhodesia. Or maybe he doesn’t. After all, it’s awful hard to get there and all that really matters is that he comes back a week later with a tan, a practiced pitch, and maybe some plausible pictures of an underperforming African mine.

“After performing rigorous due diligence investigations, Axe Capital has concluded that Independence Mines is an unsound and potentially insolvent operation, and we have taken a short position reflecting this opinion,” reads an email from Axe’s communications officer to clients, many of whom work elsewhere in the knitting-circle of organized finance. Axe Capital is, of course, only fulfilling its obligation to keep investors informed of the decisions being made with their capital, but this seemingly innocuous statement boomerangs between Bloomberg terminals in the financial districts of the world as though it were a video of Susan Boyle singing “This is America” to sneezing pandas. A couple investment banks start slowly unwinding their positions, just to be safe. Another hedge fund recognizes the Axe-tivist fingerprints and buys their own puts.

The price of Independence drops. Not to $50, mind you, but maybe $85. It’s enough for the talking heads to take notice. Blogs are written. Screenshots of price charts are retweeted. Cosmo Kramer rants about it on NBC. “It’s a great company,” he screams, “best thing since Sendrax.” Maybe Axe himself phones a prominent anchor, reminds him of a poorly attributed quote from his ghostwritten moneygrab: “A mine is just a hole with a liar standing on top of it.” It flatters the haircut that Axe read “his” book, so he tells the world that he has it from a “trusted source” that Independence management is going to announce “big changes” at their shareholder meeting next week. Now the company is really in the crosshairs. Every MBA with a MailChimp newsletter is typing “what I’m hearing about IPM” into their daily blast. The ticker symbol seems to be permanently stuck in the chyron. Independence’s rumored troubles are in the C Block of every Street-centered broadcast: “In the past week, the price has fallen 30% on heavy trading.”

Jenny Independence, step-great-granddaughter of Independence Mines’s founder, inherited a few dozen shares of IPM but has nothing more than a sentimental stake in the company’s survival. Having watched the trading price fall day after day for two weeks, she instructs her money manager to sell at any price and recommends her brother do the same. Meanwhile, the copycat short-sellers start piling on: an eponymous “bear raid.” Independence only has 1,000 shares in circulation, but there are now nearly half that many puts on the books. By booking these puts, the “activist investors” have testified to having control of said shares and are therefore entitled to attend and even vote at the upcoming shareholder meeting, despite the fact that some of them haven’t actually found any shares to borrow yet. This is part of the reason companies regularly end up with more shareholder votes than they have actual shares in circulation.

By this point, though maybe not long before it, Independence’s CEO, we’ll call him Ira Icejuice, has noticed the inexplicable volatility of his company’s stock. He, his management team, and executive board, some of whom may actually be stationed in Rhodesia, where absolutely nothing has changed, are debating whether to make a public statement, what that statement might be, and if, by doing so, they might actually make the situation worse. “Everything is going great,” they’d say. “Nothing has changed. Come see for yourself,” they’d say. And every investor would think, “Of course they’d say that.” And, after all, it’s awful hard to get there.

Since put options can be registered anonymously, management may have no idea who is shorting the company. They will naturally try to calm the waters at their meeting with shareholders, but, depending on the company bylaws, the shorts may be able, either in person or by proxy, to challenge management’s messaging, alter the agenda, and even stall routine business. They may simply aim to unnerve the shareholders in attendance, persuading them to sell on the cheap. Whatever the disruption, the details of it will certainly leak out into the media, seemingly legitimizing the vague alarms echoing from squawkboxes throughout the preceding weeks.

Cue freefall. Management becomes desperate. Maybe somebody agrees to an ill-conceived interview. Maybe somebody gets caught on camera describing his desire to eat the shorts alive. Maybe they explore the possibility of raising capital by issuing more stock, rushing to announce quarterly earnings, revising their business model, replacing key executives, or even selling the company wholesale. Their desperate maneuverings, under a now–permanent media microscope, look like exactly the kind of things one would expect from corrupt and incompetent leadership.

Maybe at some point an angel investor swoops in, stabilizing the stock price. Maybe a corporate raider starts buying up shares with the intention of selling Independence for spare parts, slowing the freefall and putting a cap on Axe’s returns. Maybe, at that juncture, he has to hedge the trade by buying up cheap shares himself. Or maybe the bottom drops out. Maybe the company continues to work its mine and sell its ore and employ its workers and turn a profit, but its trading price drops all the way to $10 or $5 or $1, and nobody really give a shit except for short-sellers when they cash in their puts. On April 30th, Axe buys 100 shares from desperate stockholders who are just happy to get anything for them and sells them to Layman Brothers for $5000, per contractual obligation. Perhaps he needs to buy 200, so he can return 100 to a broker who never knew he “borrowed” them. Or perhaps he doesn’t and he simply bets that no regulator will ever actually check.

Don’t misread the foregoing hypothetical as a specific counter to China Hustle. I’m not calling shenanigans on Dan David, GeoInvesting, and the other activist investors featured in the film. I have no reason to disbelieve David’s allegations of rampant reverse merger fraud or dismiss his speculation that it is symptomatic of broader financial malpractice being executed beyond the frayed edges of the Chimerican co-dependency. He very well may be the kind of ethical investor the Yalies imagined, making the natural transition to Republican congressman. It’s plausible, right?

I merely want to point out that China Hustle also participates in a broader cultural defense of short-selling and activist investing that either naively ignores or willfully suppresses the propensity for fraudulence amongst this class of investors, who have largely succeeded in obscuring themselves from regulatory oversight and public scrutiny. “Activist investing” is an evident attempt to rescue the delusion of “self-regulation” by accepting hedge funds and venture capitalists specious claims to moral authority. Perhaps most importantly, any pretense they have to altruism is compromised as soon as they create for themselves a financial incentive to see their predictions realized. Why would anybody listen to Chicken Little if, whenever the sky falls, he books record returns?

In the 2010 Daily Show interview, Lewis admits, somewhat sheepishly, under Stewart’s good-natured grilling, that, as the small set of iconoclastic investors featured in The Big Short realize the extent of the risk created by mortgage-backed securities and derivatives, “At no point does anybody say, ‘This is wrong. We’ve got to stop it.’” “No, no, no,” Lewis laughs, “That doesn’t compute. That’s not even a thought that would occur to a Wall Street trader.” Instead, activist investors position themselves to profit from the inevitable catastrophe and, by so doing, further inflate the risk and exacerbate the crisis. In the middle of China Hustle, Rothstein briefly contemplates the incentives problem created by activist investing. “Maybe it says something about human nature, about why we keep getting into these messes,” Rothstein muses, considering the case of Matt Wiechert, an investment banker who “realized that hundreds of millions of dollars in Chinese reverse mergers that he’d sold were frauds,” but “didn’t react with shame, just pragmatism. He wanted to make sure he got a piece of the ride down, so he switched sides and became a short-seller, like Dan.”

“Making sure to get a piece of the ride down” is a perfect slogan for contemporary hedge fund culture. And, of course, once an investor has bought his ticket, he is predisposed to take the ride, leaning into it like a rower who capsizes the boat just to see the rest of the team get wet. Shorting, Lewis says, “is the only incentive to bring bad news into the system.” Lewis’s implication, that investors should be incentivized to bear bad news, seems peculiarly perverse, particularly when it follows from the premise that a huge proportion of the “news” upon which investment decisions are based is flawed, if not outright fraudulent. As though specious cynicism will somehow save us from baseless optimism. Lewis unintentionally acknowledges the inherent flaw in the incentive structures so celebrated by mainstream economics. When we can see the incentives it becomes hard to see anything else.

Rothstein insists that Dan David is different. And David certainly plays to this narrative, weeping over the impact of deindustrialization on his hometown and emphasizing the various public avenues he has pursued, in addition to simply shorting the companies he believes to be fraudulent. But, of course, every banker, bureaucrat, politician, and ratings agent he talks to looks right past the evidence he presents them to presume, rightly in most cases, that he is primed to profit were they to follow his advice. The structure of the short sale has, rather than effectively marshaling his self-interest in service of the public good, turned his apparent profit motive into a leper’s cloak. His status as an investor neuters his aspirations to activism.

[1] Of course, this data does not account for DVD, television and streaming rights, and thus excludes entirely the Emmy-nominated HBO adaptation of Sorkin’s book, among other things. But it’s hard to imagine that The Big Short, which has also been available on every platform, hasn’t at least sustained its enormous head start.

[2] Lewis perhaps underestimated his own popularity coming off Moneyball (2003) and The Blind Side (2006), both of which were also bestsellers adapted into blockbuster films (combined worldwide gross: $420 Million).