After reading Seven Terrors a few weeks ago and mulling upon it, I still can’t quite break free from Selvedin Avdić’s narrator’s voice and his fruitless search for his friend, Aleksa. Both are “lost” somewhere in a secular, intellectual, and “Muslim” corner of the forgotten 1990s Bosnian War. After four years of memorializing the centenary of the last-but-one war that began in Bosnia, his voice somehow seems the more authentic and “Quixotic.”

Avdić’s narrator, like Quixote, suffers the grand delusion. Embarking on a great quest on behalf of Aleksa’s daughter, our knight-errant suffers from night terrors, lapses into drunkenness and the occasional doubt but still blunders on blindly, hopefully. He also has Aleksa’s diary which finishes on the day of his disappearance, a prose treasure map leading into Hell.

As we read on, our narrator shares his Seven Terrors. It is part of the charm of this novel that our narrator also provides endnotes. That “Fear of Madness” is the sixth of those Seven Terrors provides an early clue to the mental reliability of our narrator and the plentiful darkness of the author’s humor. The Bosnian War, as told by Avdić is a tale of trolls in mines, devils incarnate, and Don Quixote bumbling along with his quest: falling in love with Aleksa’s daughter one day, another day being too tired to leave his bed.

Despite being a novel written in an “Eastern European” setting, there are vast amounts of allusion to “Western Popular Culture” in the text. These affectations in turn allow the reader to note that, rather too frequently, “difference” in this novel relates to participants in an inexcusable bloodbath. The 1990s, remembered so affectionately in other parts of the world, are only made plausible and authentic in Bosnia by representing Genocide as the work of the devil and his many helpers.

That said, I would like to meander again into the format of this novel. It is very, very funny. It is probably best enjoyed without any knowledge of Bosnia in the 1990s. The text also has many “bonus features.” The endnotes and list of terrors have already been mentioned but also, right at the end of the text are seven empty pages for the reader to list his or her own terrors, a further example of the author going well beyond blackness and entering a kind of satirical engagement with his reader that could only be described as hyper-emptiness.

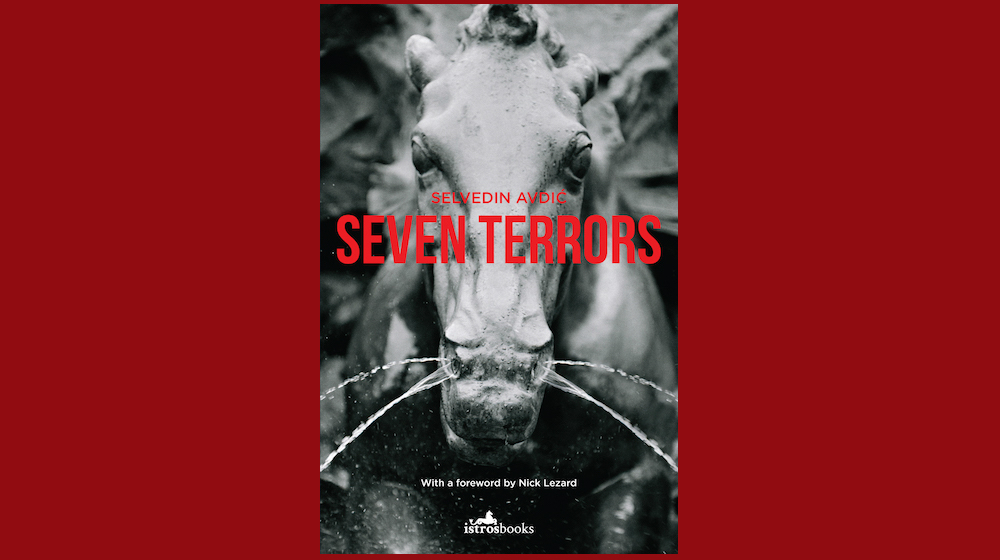

Nick, now calling himself Nicholas Lezard, a noted British literary journalist who has written much about his own terrors, has written an introduction which is a work of art in itself. However, I would encourage the reader to read that afterwards and make up his or her own mind on whether it was written for Seven Terrors. I read a different book.

I should also add a further note on Selvedin Avdić’s splendid deployment of his narrator as a kind of super-sized Oblomov, if one could possibly imagine such a weighty lump to be even more useless. In Ivan Goncharov’s satire on the Russian Lesser Nobility, Oblomov takes about 90 pages (in the English version) to actually leave his daybed. In this delightful English translation, Coral Petrovich gives us the marvelous calumny of our narrator spending nine months in bed in “self-imposed exile” before being inspired to investigate his friend’s disappearance. Seven Terrors is simply awesome.