By Alex Harvey

Back in 1939, Aldous Huxley’s first Californian novel, After Many a Summer Dies The Swan, satirized the local obsession with and search for eternal life. Huxley created a protagonist, Jo Stoyte, a classic Hollywood magnate, who spends his fortune on a quest for personal immortality. Stoyte wants to arrest time; he hires a scientist, Dr. Obispo, to find a breakthrough in medicine that could ensure eternal life. Separate from his personal quest, Stoyte is also the owner of a mortuary. He is happy to profit from the deaths of others. His cemetery is successful, moreover, precisely because it presents itself as a kind of abolition of death. Pordage, the historian, reflects that death has been vanquished in the mortuary not by freeing the spirit from the moribund body, but by “preserving that body, injecting it with embalming fluids, painting over its pallor, twisting its grimaces into the likeness of a smile.” Stoyte’s dead bodies appear to be living even after death. In the ever physically optimistic California, Huxley prophesizes, “the crones of the future will be golden, curly and cherry lipped, neat-ankled and slender.”

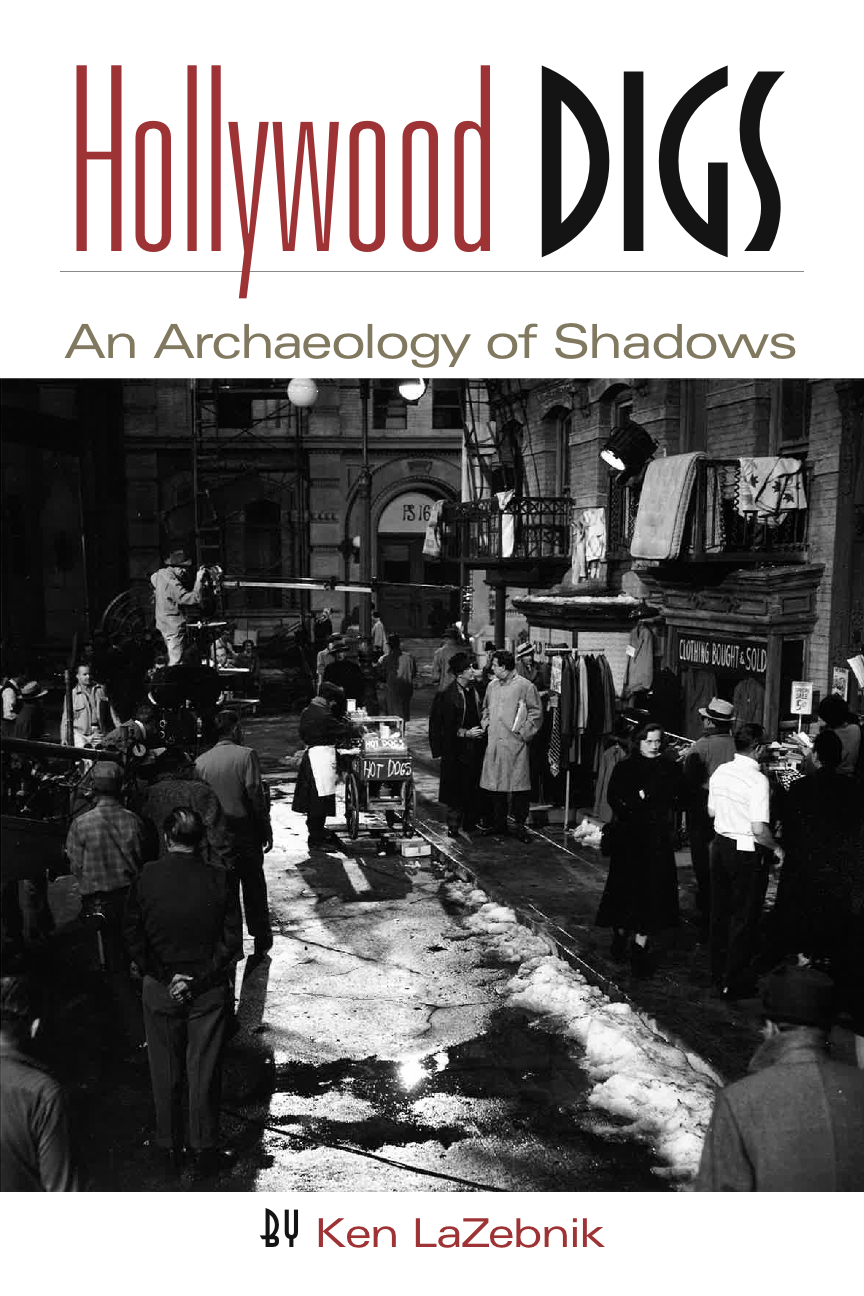

75 years later, Huxley’s vision of Los Angeles as a city locked into a paradoxical fixation with and denial of death rings truer than ever. In Hollywood Digs: An Archaeology of Shadows (2014) local writer Ken LaZebnik explores the strange warping of time and place that the movie industry has helped to create and sustain. His book is a small treasure trove of hidden stories of writers, directors and actors. Pen portraits of the once famous and now obscure jostle alongside more personal anecdotes. Photographs culled from a somewhat sinister corporate entity called The Hollywood Vault are placed alongside eclectic finds from Studio City estate sales.

In digging through Hollywood’s underground history, LaZebnik is particularly concerned with death. He tells the sad story of Jock Mahoney, the 13th Tarzan and legendary stuntman (the movie Hooper was part tribute and starred Mahoney’s step-daughter Sally Field), who contracted dysentery after jumping from a plane into the reservoir of a sewage treatment plant: “His body, that tremendous resource, the extraordinary athleticism upon which he had constructed his career and livelihood, was now wasted.”

We learn how actor and producer Dick Powell’s early death from cancer arose from an ill-fated movie called The Conqueror, shot near a nuclear weapons testing site. Despite Government officials assuring Powell that the location was safe, ninety-one members of the cast and crew were diagnosed with cancer (the dead included John Wayne and Agnes Morehead). According to LaZebnik, “Howard Hughes so regretted the project that he bought every copy of the film for 12 million and had them all locked away in his Las Vegas apartment, where he obsessively viewed the film as his fingernails endlessly grew.”

In every shard of movie history or biographical fragment that LaZebnik unearths, he strives to negotiate its relation both to death and to timelessness. Rooting through the bric-a-brac at a garage sale off Ventura Avenue he discovers the artifacts of a dead actress. After leafing through the framed photographs and assorted posters from Broadway shows, LaZebnik works out that he is in the home of Elizabeth Allen, an actress once nominated for a Tony for her starring role in the musical Do I Hear A Waltz. Allen’s high water mark in her later Californian days was her TV persona as a wise and maternal wife, providing stability to the ineffectual husband on The Paul Lynde Show. Wandering through the house, searching for other clues to her life, LaZebnik has a small epiphany: “Elizabeth’s books were on the market and as I looked through them I realised she had the same collection of Chekov’s plays, the same edition of Uta Hagen’s ‘Respect for Acting’ that I owned. It suddenly struck me that everyone in late twentieth century theatre had an identical shelf of ageing paperbacks.” In this melancholic, Larkin-esque mood, LaZebnik is accosted by a strange Italian woman. She whispers to him that she is the sister of Sergio Franchi, a popular Italian singer, beloved of Las Vegas and The Ed Sullivan Show. “They had a big romance. During the show. A very big romance. Very intense,” she tells him. Later, when he checks Elizabeth’s Allen’s on-line obituary, LaZebnik finds reassurance in the fact that she and Sergio are there pictured together, forever framed as a couple.

LaZebnik also rescues from the limbo of obscurity other figures, whose faint, receding remembrance is less exalted. Take, for example, the comedian Milton Berle, or “Mr Television”, the man whom eighty percent of Americans watched each week in 1950. Now almost completely forgotten, Berle was once rumored to be the most well-endowed man in Hollywood. At his memorial service a fellow comedian declared, “On May 1st and May 2nd his penis will be buried.” And In Truman Capote’s short story, “A Beautiful Child,” Marilyn Monroe remarks: “Everyone says Milton Berle has the biggest shlong in Hollywood.”

LaZebnik explores Monroe’s own iconic death in detail. At The Hollywood Vault, LaZebnik unearths an extraordinary box of photographs, taken by Leigh Weiner. He was the only photographer to get shots of Monroe in the Westwood mortuary. According to his son, Weiner brought three bottles of Scotch to the morgue door and talked his way in.

“I guess they have her down in Santa Monica,” Leigh said.

“No,” one of the guards replied. “She’s right here.” And he pointed to a wall of refrigerated doors.

“You want to see her?”

“Sure.”

They pulled open the drawer that held the body of Marilyn Monroe. She was covered by a sheet. Leigh took pictures of the scene, of the guards, the drawer, of Marilyn’s foot with a tag on it. When the guard asked the photographer if he wanted him to pull the sheet off, Leigh replied, “Sure.” The guard pulled off the sheet. Marilyn lay in it, nude, autopsied. Leigh took the shots. But later the photographer decided he could not sell or show the photographs he had taken of Marilyn’s body… It would be disrespectful.

Here LaZebnik uncovers a perfect, paradoxical, Hollywood moment. Even in the very morgue itself, naked and exposed in all her mortality, the power and allure of such a movie star puts out a kind of protective, timeless shield. In turn, the story of her death builds and creates a myth. She becomes a true icon; she moves into her after-life.

F. Scott Fitzgerald endured a kind of living death in his final three years in Hollywood. Failure is “la petite mort” of the movie industry. Out of contract as a screenwriter (he managed only one on-screen credit for Three Comrades), and with his book royalties dried up (all of his novels earned less than 20 dollars in 1939), Fitzgerald was forced to move into a cottage on an estate at Encino, aptly named “Belly Acres.” His landlord, Edward Everett Horton, was a hugely successful, empty-headed actor. He specialized in playing comic butlers and was given to boasting that he had ceased “all mental activity at the age of eighteen.” Fitzgerald was churning out the self-satirizing Pat Hobby stories for Esquire whilst drinking ever more heavily (his secretary would dump burlap bags of empty gin bottles into the brush along Mulholland Drive). His rent was paid by the woman he was seeing, a Hollywood gossip columnist called Sheila Graham (she claimed to be a bone-fide English aristocrat but grew up in full Cockney, East End poverty). Graham’s son, Robert Westbrook, wrote about his mother’s relationship with F. Scott in his last Hollywood days. She once confessed that she had never read any of his novels. To remedy the situation Fitzgerald determined to purchase his books that very evening. The first two bookshops they visited had none in stock. There had been no interest for some time. They found a third book seller, an old man who promised he’d try and track down copies of The Great Gatsby and Tender is the Night and asked for a name and address.

“I’m Mr. Fitzgerald,” Scott said defiantly. The man reacted with shock and said he was very happy to meet him. But it was clear why the old man had been so surprised when Scott revealed his name; he had believed, quite simply, that Scott must surely have died years ago along with his era.

Edward Everett Horton Lane still exists in Encino but, as LaZebnik notes, there’s no street in Los Angeles named after the outsider, F. Scott Fitzgerald. It wasn’t his town.

Failure is not something to be admitted in Hollywood, and in such stories as “The Crack Up,” Fitzgerald is positively garrulous about his own shortcomings. In this, he shares some common ground with LaZebnik: in the most personal chapter of Hollywood Digs, LaZebnik faces up to his own failure (and death to the industry) when he recounts his inability to deliver the type of script that his TV producers demanded. Like Fitzgerald, he too becomes an outcast, carrying a carrion stench.

“Ken, this isn’t working. We’re going to let you go. I’m sorry.” I hung up the phone. I was now officially on the outside. An assistant would pack up my things and deliver them in a box to my house. I felt like a man out of time. I had tasted the bitter grapes of failure. I could no longer pretend that success was an aura surrounding me and glowing like an over-exposed shot of film. The only response could be to bury this episode of death deeply.

Instead of the personalized parking space on the studio lot, LaZebnik is consigned to shuffling along the streets of Studio City, passing its Fifties cottages and ranch houses. He peers through gaps in the ever-present developers’ fences as his neighborhood loses another slice of history: the old Spanish style duplex where Donald O’Connor gave his tap dance lessons, the neighboring home of Farley Granger, still venerated for his roles in Hitchcock’s Rope and Strangers On a Train. At another local garage sale he enters the spacious home of a former president of the Writers Guild Of America, the enormously successful Mel Shavelson (his jaunty autobiography is titled How to Succeed in Hollywood Without Trying, P.S –You Can’t). In Shavelson’s last, ninetieth year, he summed up the significance of his life’s work:“The important thing about a motion picture is that it lives longer than almost anything else… It will live after I’m forgotten. To me, when I see those pictures and I see the actors, I say to myself, ‘Those actors – how fortunate they are – they’ll never get any older’… The pictures I made 20, 30, 40 years ago, they still get seen today.”

Huxley satirized just that warped sense of temporality in Summer. He also saw how tangibly the Californian mindset was able to impact the very fabric of Los Angeles.When the historian, Pordage, is picked up and driven from the airport through a version of Beverly Hills, the landscape appears like a weird mash-up of museum, cemetery and repository of world religions. It resembles a museum in the way it equalizes all periods in time and all locations in space. Any disparate architectural style can be juxtaposed: Mock-Tudor manor houses next to Modernist cubes; Rococo pavilions and Mexican style haciendas. These buildings, mystically abstracted from the time and place to which they belong, can house a latter day divinity, a saint, a vacuous image – in other words a movie star. The chauffeur excitedly points out to Pordage that Ginger Rodgers lives in a reproduction of a Tibetan lamastery.

At the end of Hollywood Digs LaZebnik recalls repeated sightings of a thin, elderly man pushing a loaded shopping cart in his Studio City neighborhood. At first he assumes the old man is homeless, collecting a load of useless detritus. Eventually he finds out that the man is taking home bits and pieces of discarded set dressing from the films he has worked on. He turns out to be the make-up artist who worked for Marlon Brando, Philip Rhodes. Philip recalls a time “late in Brando’s life when everything was going wrong.”

His son Christian, in a drunken stupor, shot and killed the Tahitian lover of his half-sister, Cheyenne, and went on trial for murder. Brando was despondent. The neighbors on Cantura Street would see a long black limo come down from Mulholland Drive. It would first stop at the Baskin-Robbins Ice Cream Store. The driver would get out and purchase an entire tub of ice cream. Then it would pull up in front of his (Philip’s) house. Philip would emerge and get in the limo.

It’s another moment out of time: Brando with his make-up man, sitting in the back of the limo, slowly eating ice cream together. Maybe, as an after-life, this is right: a place to sit and share your thoughts with someone who never judges but only tries to make you beautiful, whose whole art is to arrest time.