A bloody Homer Simpson with spear through temple; a taxidermied wolf; a tragic love story staged in a wrestling ring. LA Louver’s survey of Terry Allen, which ran June 26 through September 28, 2019, was an assorted, six decade-long anthology of drawings, photographs, stage-plays, installations, sculptures, and video works. Despite this scope, Allen’s career consistently appears as a reconstruction of personal history and inherited memory. In this way, narrative becomes the most distinct of the many materials in his repertoire. If there’s any one label with which to define the multifarious Texan, it’s storyteller.

Allen’s autobiography constantly works its way into his work. He was born in 1948, the grandson of a Civil War veteran and son of a turn-of-the-century professional baseball player who, by the time his son was born, was in his 60s. The elder Allen takes on a mythic omnipresence throughout the exhibition. Existing as a series of drawings, installations and a radio play, Dugout (1999-2006) is assembled from stories told to the artist by his parents. For Blood depicts thick, ink-black fingers, jutting and gnarled with blood-red slashes. The hands frame a block of text that recalls fingers broken in gameplay and a bloody, cleat-related assault committed by a sliding Ty Cobb — stories from the artist’s father that ultimately illustrate the maxim: “That’s the only way the game is played… with heart and for blood.”

“Warboy” appears throughout Dugout, often as a caricature and sometimes as an oversized puppet. The character serves as an avatar for the adolescent Allen, illustrating how the stories one is told in childhood maintain a puppet-like mastery over us as we grow older. Of course, many of the stories coopted for the series read more as hyperbolic Western fables than as real events. But Allen suggests true stories and falsehoods can be equally imbued with fanaticism, grandiosity, and wit. If these stories continue to pull the strings of our personhood, whether or not they are true is ultimately irrelevant. Veracity matters less than these narratives’ ability to manipulate their recipient.

The 1975 concept album Juarez similarly entangles elements from Allen’s personal life into an elaborate cowboy odyssey. Through songs and spoken word intervals, the record tells the story of two pairs of wayfaring lovers, traversing the Southwestern landscape until their paths cross in a deadly melee. Similar to the couples in the story who gallivant from the Mexico border to the American West and California, Terry and his high school sweetheart-turned-wife, Jo Harvey, left Lubbock, Texas for Los Angeles in 1962. Longing for the transformative and quintessentially American promise of the West, the young newlyweds ventured to the Pacific with a “need to get out into the world, without any real reason other than curiosity.”

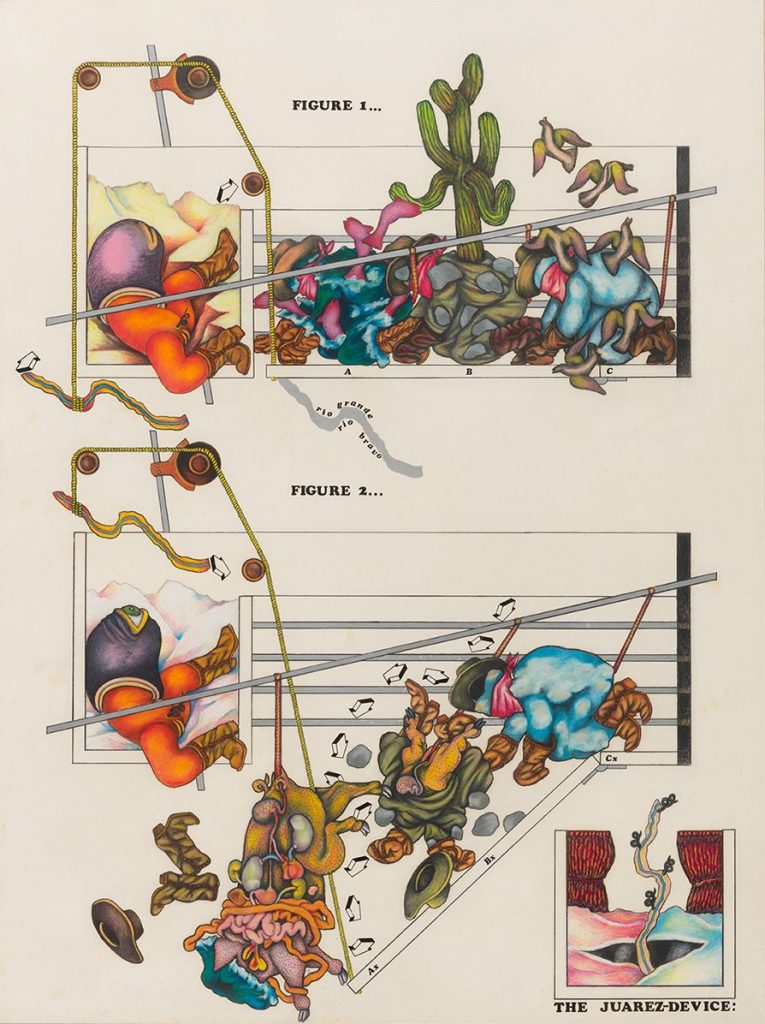

The record is presented here in both musical form and as a series of drawings. In Juarez Device, windswept amoebic forms pirouette with cowboy hats, boots, cactuses, and an assortment of other country-western signifiers. While these enmeshed, multi-colored phenomenon recall abstract expressionist and surrealist motifs, everything is structured around a diagrammatic pulley system. Like the concept album, these drawings meld the imagined and fantastic with the rigid chronology of real-life experience.

Juarez Device, 1969 – 1975; mixed media on paper and plexiglass.

In this way, Allen makes it clear that our supposed reality is shaped as equally by the truths that we’re told as by the lies that we believe. Youth in Asia (1981-1983) grapples with the aftermath of the Vietnam War through drawings, sculptures, poetry and a radio play. The multimedia Sneaker centers around a washy depiction of a plane, mid-flight in a dusk-red sky, inlaid at the apex of two surrounding canvases. A brown leather dress shoe protrudes from the surface of the middle canvas, while a second lingers from a metal box at the bottom of the piece. Mustard yellow block text is perpendicularly stamped into the lead surface surrounding the airplane.

The text is coopted from a real newspaper article about a former POW. Upon his return home, the soldier would become aggravated when his family wore shoes in the house, the floorboard squeaking evoked memories of the sounds made by his former prison guards. After his death, the military informed his widow there was no record of him having served in combat. Despite this curious outcome, the legitimacy of service is ultimately secondary to its subsequent trauma. Ultimately, it’s the recollection of combat that injures the soldier and, subsequently, his family. With this trauma comes the reality of war. Memories, whether real or imagined, can often be as vivid and potent as the moments they recall.

Sneaker (91.20.D), 1991; mixed media.

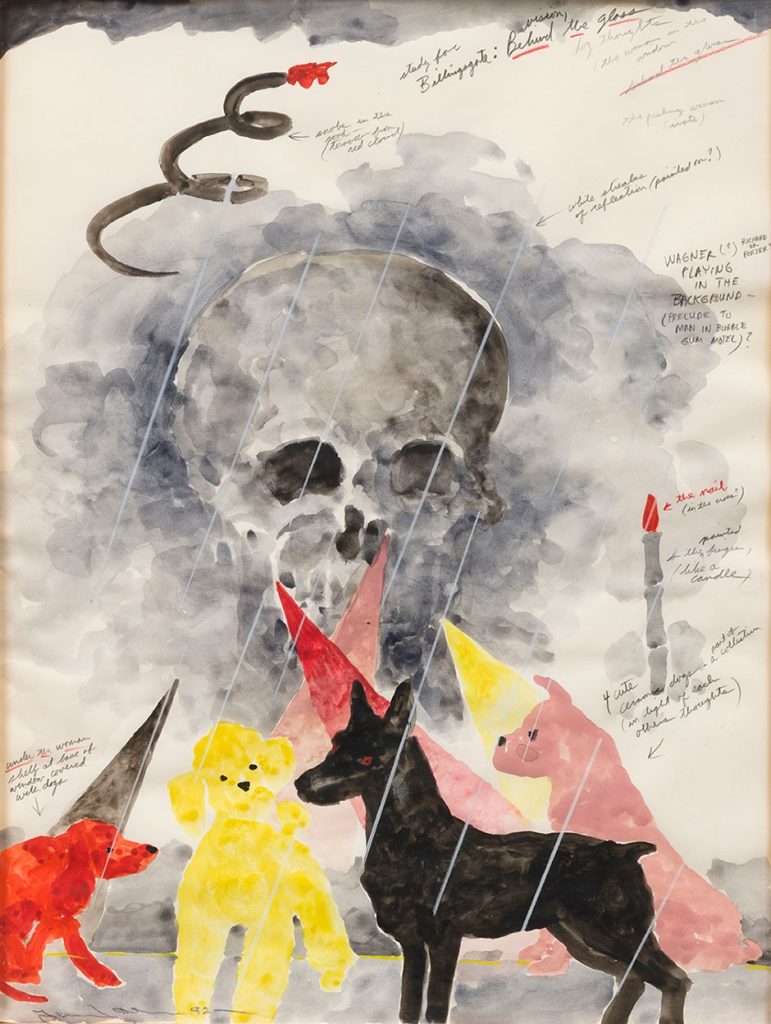

In this way, if lived experience ultimately metamorphoses itself into images and narratives along the highway of memory, who’s to say to fictional devices can’t be just as tactile as the supposedly real? In, Billingsgate (1982), Allen uses the mechanics of memory as a means of reproduction. After being commissioned by the city of Billings, Montana, Allen created a replication of the motel room he stayed in during his initial visit. A to-scale reproduction was built in the Yellowstone Art Center, its surrounding wooden frame left exposed. Viewers were able to peer into the simple room, complete with replications of the original furnishings.

Vision Behind Glass (Billingsgate), 1983; mixed media on paper.

In actuality, the furniture was hollow copies — empty forms stuffed with dirt. The installation differs from the original only in this subtle interior discrepancy. Similarly, memories are absent of an interior. Without a body, without tangible substance, they only refer to a discrete time and place. Thus, as with memory, the verisimilitude of a work like Billingsgate to a “real” event is outdone by its capacity for recollection — to invoke rather than replicate. What’s inside doesn’t ultimately matter, whether cushion or dirt. Memories, like stories real and imagined, are hollow, often devoid of a physical presence altogether. But that doesn’t make them any less impactful.

Whether it be the recollection of trauma featured in Youth in Asia or the excavated motel room in Billingsgate, the stories in Allen’s toolbox are ambiguous in their relation to the truth. Others, such as those recounted by his father and grandfather, are mythologized merely by their historical distance. But these narratives are animated as they come into contact with Allen. They are not merely indexed; they are imprinted onto him. In this way, the viewer experiences Allen as a conduit of memory- an artist reconstructing and reverberating the voices and experiences that have shaped his personhood. Ultimately, these stories become real, less in their proximity to the truth than in their continued manifestation in Allen himself.

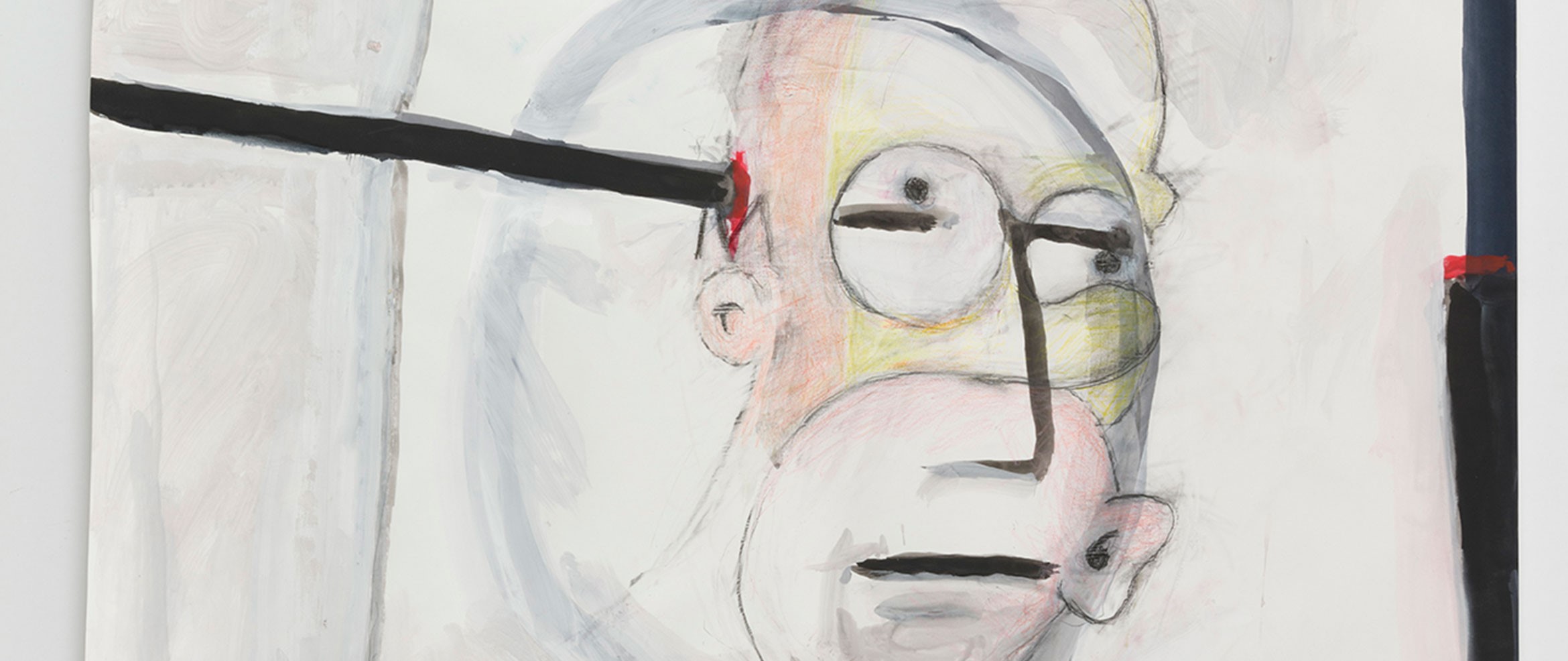

Cover image: from Homer’s Notebook 2, 2019; mixed media on paper.