The indications that John Cena was created in a laboratory are not few. They include: his hulking physique, more suggestive of metal than stone; his almost absurd generosity, which has compelled him to fulfill more Make-A-Wish wishes than any other human being; and his acting chops, which have catapulted him from the wrestling ring to the silver screen. Cena most recently appeared in Bumblebee, the latest flick in the Transformers franchise, as military hotshot Jack Burns, an agent of the US’s clandestine alien-monitoring group Sector 7. As Burns violently tracks down the film’s titular robot, he embodies a hyper-masculine, jingoistic American military ethos — that is, until the movie’s end, when he recognizes that Bumblebee’s alien-ness does not necessarily make him a foe.

It is in Cena’s character — in how the film frames and ultimately forgives his villainy — that Bumblebee expresses its ideological underpinnings. Though the film’s politics strive to be more progressive and refined than those of the American state during the Cold War, which serves as the movie’s historical backdrop, they turn out to be entirely tepid, bland, and ineffectual. They are, in other words, squarely at home in both Hollywood and the capital-R Resistance.

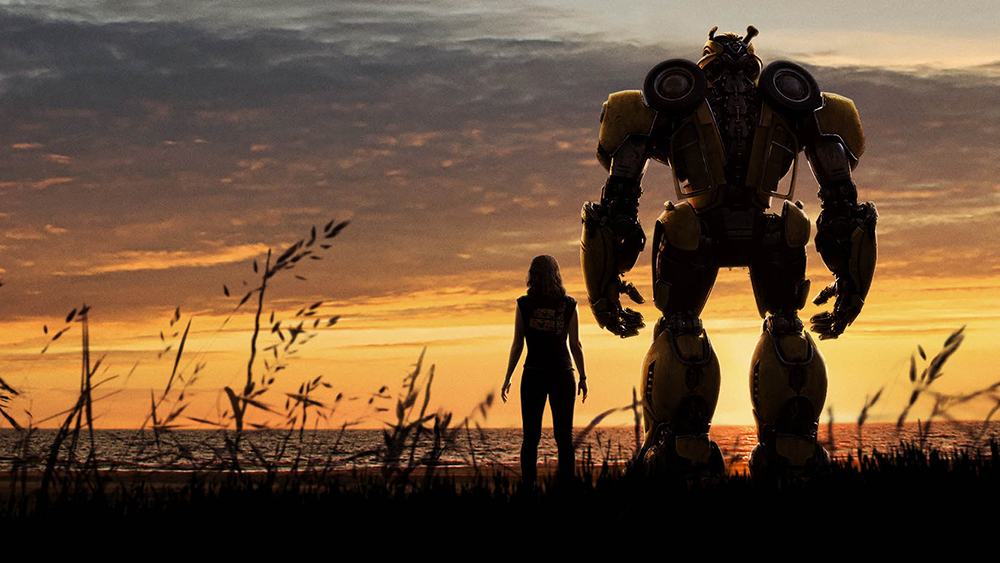

Bumblebee crash-lands in California after the Autobots (the good Transformers) lose a war against the Decepticons (the bad Transformers) on the distant planet Cybertron. After suffering immense damage during the landing, he takes the form of a beat-up VW Beetle and hibernates until teenage mechanic prodigy Charlie Watson (Hailee Steinfeld) finds and repairs him. The fall, however, has left him amnesiac and speechless. A quite pleasant teenager-robot adventure ensues, but it is interrupted by the arrival of two Decepticons, who have correctly figured that Bumblebee holds information about the rest of the surviving Autobots. The Decepticons link up with Sector 7, which shares an interest in finding the mysterious alien robot that’s hiding in American territory.

As a film, Bumblebee repeatedly emphasizes its 1980s setting, from Watson’s adoration of the Smiths to a shot of a Reagan portrait in Burns’s office. The movie’s primary historical mission is to explore, through fairly stereotypical characterizations, the intersection of three generations: Baby Boomers (through Burns, a military man who likely came of age during the Vietnam War), Generation X (through Watson, an angsty latchkey kid), and Millennials (through Bumblebee, whose amnesia severs him from his historical context, and whose damaged speech system leads him to communicate by dialing his radio to certain songs, effectively forming a personal identity through pop culture). Though Bumblebee’s status as a pseudo-Millennial in the 1980s is ahistorical, it facilitates the film’s dual commentaries on the Reagan years and contemporary America. The saga of the generational trinity plays out as Burns, the Boomer, fails to rein in Watson, the Gen Xer, who socializes Bumblebee, the Millennial, by teaching him how to blend in with humankind and exposing him to pop culture.

The conflict between Burns and the Watson-Bumblebee duo resembles a seesaw: on one end, Watson tries to ground Bumblebee by rendering him inconspicuous; and on the other, Burns raises hell as he searches for Bumblebee, jolting the robot out of Watson’s control. Eventually, Burns applies too much weight and nearly kills Bumblebee — but when Watson revives the Transformer, he regains his memory and fights Burns with unprecedented fury. So while Burns perceives Bumblebee to be a grave threat to civilization, he fails to see how his own behavior has pushed Watson and Bumblebee further and further toward violent rebellion. It all comes full circle.

The grand political vision the film espouses is one of generational reconciliation. In order to realize that vision, it works to make each representative likable enough to warrant a truce. The movie evokes sympathy for Bumblebee from the get-go: he has a tragic backstory, he is dog-like in his adorableness, and his use of music as speech is genuinely charming. Watson, while a bit abrasive, is also endearing: we learn that her father died prior to the events of the movie, and she is still reckoning with both his absence and the intrusive presence of her stepfather. Her angst is understandable and believable. Burns, in contrast, is a big lift as far as likability goes. He may be less dangerous than the Decepticons, but it’s easier to despise him given that his evil is informed by Reagan rather than something extraterrestrial.

The film lets Burns off easy, though, by failing to interrogate the malice of his ideology. It’s true that Burns’s perspective on Bumblebee is fair: when confronted with uber-armed sentient robots, one would be wise to err on the side of caution. Accordingly, Burns initially resists teaming up with the Decepticons because he doesn’t trust them enough to let them access Sector 7’s surveillance network. But his commanding officer persuades him by explaining that the alliance would give the US leverage over the Soviets. To its detriment, the film doesn’t probe this familiar and flawed logic — no one questions the notion that gaining geopolitical strength is worth compromising the rights of Americans and aligning with unsavory political actors. Bumblebee doesn’t really care what Burns thinks about the US’s role in the world and its perpetual accumulation of power. Rather, the only conflict that concerns the film is Burns’s pursuit of its heroes. Burns is thus a flat villain, his antagonism stemming not from his political convictions but from the simple fact that he opposes the protagonists.

The straightforwardness of Burns’s villainy allows the film to redeem him with minimal effort. Toward the end of the movie, after watching Bumblebee valiantly battle the Decepticons, Burns’s opinion of Bumblebee flips and he salutes the robot. Bumblebee responds by jutting his fist upward, a move he learned from The Breakfast Club. This interaction is the film’s clumsy attempt at a political resolution: a peace-making between the old guard and the alien newcomers, between Boomers and Millennials. The movie imagines a compromise that could expand the ideological center to encompass Burns — the right — and Watson and Bumblebee — the left(ish). But what it actually offers is quietude at the cost of human progress. For, in the world at large, the center rarely grows to absorb the left. Instead, as the film demonstrates, it inches rightward, morphing into something slightly more reactionary.

As the US’s ideological center reliably moves to the right, it operates like a vacuum, sucking in the space and thought around it, gathering diffuse particles into a homogeneous mound of grey. It is in that mound that our contemporary Resistance lives. There, in the mound, we can think of ourselves as “progressives” while we revere the intelligence community; we can canonize “liberal” heroes who advocate for mass deportation and maintain that corporations are people; we can mistake doing nothing for doing good, feeling nothing for feeling good. There, in the mound, is where Bumblebee abuses the smooth, kind John Cena, weaponizing his supreme likability as a vehicle for half-baked centrism, giving demigod-like shape to the cognitive dissonance that has long marked American liberalism. There, in the mound, is where we can simultaneously salute Burns and raise our fists with Bumblebee, honoring a nation transformed but unchanged.