WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange is probably the closest a computer hacker has come — or will ever come — to being a celebrity. He’s pals with PJ Harvey; Pamela Anderson writes love poems about him. Doc Martens, the shoe company, even named a combat boot after him.

There’s no shortage of good writing on Assange. When the New Yorker profiled him this past summer, they featured an image of the mighty hacker — blue piercing eyes, shock of messy white hair, a crisp gray shirt buttoned to the throat — that made him look like a hero. While his critics consider him a massive threat to personal privacy (and also democracy), his admirers view him as a recluse on the cusp of a historical upheaval and compare him to the titular character of Philip K. Dick’s novel, The Man in the High Castle.

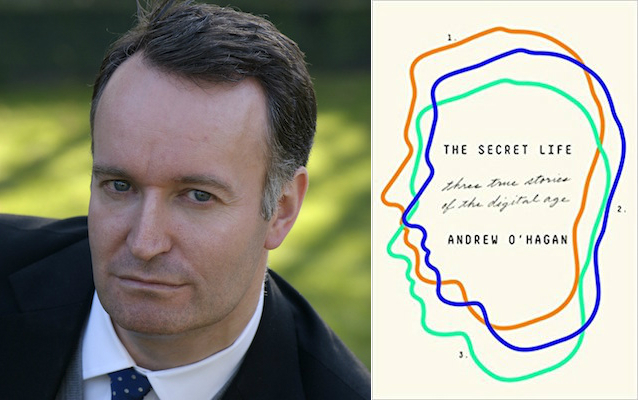

Understanding that heroic reputation is precisely what Andrew O’Hagan takes on in “Ghosting,” the first essay in his terrific new essay collection, The Secret Life: Three True Stories of the Digital Age. On its most basic level, “Ghosting” — first published in the London Review of Books — is about O’Hagan’s experience ghostwriting Assange’s autobiography. “Ghosting” reads like a cross between memoir and magazine profile. His instinct is to write about Assange by exposing the parts of his personality that contradict with his online identity. It’s a good approach for O’Hagan, who is perhaps best known as the author of five novels and knows a thing or two about inventing characters.

“[Julian] talked as if the world needed him to talk and never stop,” O’Hagan writes, “he seemed like a manifestation of the hyperventilating chatroom.” After O’Hagan finishes the first draft of the book, Assange balks — he decides he doesn’t want to move forward with the book, apparently more comfortable revealing other people’s secrets than his own. “[Assange would] rather spend hours Googling himself than have his own say in the pages of his autobiography.” But the contract is already underway, and O’Hagan soldiers on; Canongate eventually publishes O’Hagan’s Julian Assange: The Unauthorized Autobiography, possibly the first unauthorized first-person account of its kind.

O’Hagan isn’t so interested in the feud or sharing his side of the story — though he does lob plenty of zingers in Assange’s direction — instead the essay reconsiders Assange and his complexities in the context of trying to capture his true story for the book. O’Hagan’s task transforms into a bigger question about how “the world might be more ghosted now than any time in history.” “Ghosting” is really about the way Assange’s identity is complicated by the “digital era.” He may be a recluse and hero online, but he’s completely different in real life. This isn’t to say that Assange’s online self is less real. In fact, the opposite may be true.

O’Hagan provides a close examination of Assange in real life. The essay is filled with detailed descriptions of, for example, Assange’s kitchen table, how he eats lasagna with his fingers, the sexist invectives he uses to describe journalists. O’Hagan uses these details of Assange to construct a portrait that is independent of his internet personality. In many cases, O’Hagan gleans incredibly revealing quotations from Assange who, in one instance, offers a completely bonkers assessment of Nick Davies, a journalist for the Guardian: “‘The problem was he was in love with me,’ said Julian. ‘Not sexually, but just in love with me.’” He says the same thing about the Icelandic politician and activist Birgitta Jónsdóttir.

It’s no surprise that the Man in the High Castle version of Assange is mostly an invented persona, but — in this “digital age” — that doesn’t make it any less real. O’Hagan observes how it’s possible for the public image of Assange — the one that regularly appears in magazines and newspapers — to exist alongside the Assange that lives in exile, eats lasagna with his fingers, and grossly misreads journalists.

Studying Julian Assange is — as O’Hagan suggests — best done by considering his contradictions, which “Ghosting” dives into headfirst. How, for example, can the man advocate for sharing information and still force his employees to sign a document that requires them to not reveal information about WikiLeaks? Or how serious is Assange about his cause when he regularly obscures basic facts about himself?

This assessment of Assange is terrific not only because it’s unexpected, but also because it offers a bigger picture of pluralized identity that is byproduct of engaging with technology. Yes, Assange doesn’t live up to the myth, but this is inevitably true, for celebrities, and for anyone on social media. O’Hagan’s take — Assange is both the possessor of big secrets and a stunted individual who obsessively Googles himself — makes for a more complicated and believable portrait. “I felt quite sorry for Julian.” O’Hagan confesses by the end, “And I continued to feel sorry for him. He was in a horrible predicament […] He didn’t know who he wanted to be. His remarks, as always, were ostentatiously conceived and recklessly stated. He didn’t know what to believe.”

In O’Hagan’s essay “The Satoshi Affair” — also first published in the London Review of Books, where O’Hagan is an editor — the focus is directed to Craig Wright, an Austrialian hacker who claims to be Satoshi Nakamoto, the pseudonymous creator of Bitcoin, which has been called the “biggest invention since the internet.” Since the cryptocurrency’s release in 2009, Nakamoto has remained anonymous, which has only amplified the intrigue into his actual identity. In late 2015, O’Hagan was contacted by a PR company who claimed that Nakamoto was ready to come forward with his story. According to the PR folks, Nakamoto was Craig Wright, a man who had up until this point lived quietly in a suburb of Sydney.

It’s then that “The Secret Life” begins not only to be about computer hackers but, more broadly, about the way that the internet has allowed people to have contradicting identities. Wright’s online self was grossly different from his physical one, a scenario that created too much doubt for those close to the story, including Wright. O’Hagan writes, “[Wright] might have sabotaged his own proof or simply flunked the paternity test because he isn’t the right man, but his doubts about himself are the real drama.” If Craig Wright can be Satoshi Nakamoto, then anyone can forge a new identity online. More intriguing, however, is the cost of building an online self. After spending months with Wright, O’Hagan believes that Wright’s contrasting identity was enough to wipe him out entirely.

By the end, it’s not clear if he’s actually the founder of Bitcoin. O’Hagan — like many others — is skeptical, but his knack for documenting Wright’s contrasting identities, and the aftermath of his botched outing as Satoshi, are what makes this essay successful.

Sandwiched in between these two essays is a relatively short piece called “The Invention of Ronald Pinn.” The essay is a natural extension of O’Hagan’s consideration of online identity. By stealing the name and credentials of Ronald Pinn — a young man who died of a heroin overdose in 1984 — O’Hagan attempts to build from scratch a new life. The objective is, to say the least, ambitious. O’Hagan looks to “take a dead young man’s name and see how far [he] could go in animating a fake life.”

Because every online identity in the 21st century has an element of invention, O’Hagan contends that his invented avatar began to live a semblance of a real life or least as real as anyone else is online. “Ronnie Pinn’s only handicap lay in his failure to materialize physically, but, nowadays, that needn’t be a problem: everything he wanted to do, he could try to do, except find a partner, but even that, though tricky, was not impossible.”

I think O’Hagan oversteps here. While he is careful not to claim that he brought the man back to life, he does suggest in subtle ways that his newly animated avatar is lifelike. The internet may be a wild west — an unregulated marketplace where people can hide in the shadows and be whoever they want to be — but Pinn has, of course, not become something lifelike. Not really. For starters, he doesn’t interact with people apart from the dark web chatrooms. Acquiring a mailing address, driver’s license, and social media accounts doesn’t equate to inventing a legitimate online identity. Assange and Satoshi are believable precisely because of their gaping contradictions and flaws, not because they know the darkest places on the web.

It’s a small overstep in an otherwise ambitious and thrilling essay. Near the end, O’Hagan surfaces as a foil to Pinn. “It wasn’t Ronnie I was seeing: I was seeing myself, a boy of similar age who somehow knew these places well, and hung about in the unrecorded life.” The Secret Life is worth reading for this very reason. The book’s subjects may be inscrutable and fraudulent, but O’Hagan is alive and believable on every page.