For the Provocations series, in conjunction with UCI’s “The Future of the Future: The Ethics and Implications of AI” conference.

This is an essay about lists of moral principles for the creators of Artificial Intelligence. I collect these lists, and I have to confess that I find them funny.

Nobody but AI mavens would ever tiptoe up to the notion of creating godlike cyber-entities that are much smarter than people. I hasten to assure you — I take that weird threat seriously. If we could wipe out the planet with nuclear physics back in the late 1940s, there must be plenty of other, novel ways to get that done.

What I find comical is a programmer’s approach to morality — the urge to carefully type out some moral code before raising unholy hell. Many professions other than programming have stern ethical standards: lawyers and doctors, for instance. Are lawyers and doctors evil? It depends. If a government is politically corrupt, then a nation’s lawyers don’t escape that moral stain. If a health system is slaughtering the population with mis-prescribed painkillers, then doctors can’t look good, either.

So if AI goes south, for whatever reason, programmers are just bound to look culpable and sinister. Careful lists of moral principles will not avert that moral judgment, no matter how many earnest efforts they make to avoid bias, to build and test for safety, to provide feedback for user accountability, to design for privacy, to consider the colossal abuse potential, and to eschew any direct involvement in AI weapons, AI spyware, and AI violations of human rights.

I’m not upset by moral judgments in well-intentioned manifestos, but it is an odd act of otherworldly hubris. Imagine if car engineers claimed they could build cars fit for all genders and races, test cars for safety-first, mirror-plate the car windows and the license plates for privacy, and make sure that military tanks and halftracks and James Bond’s Aston-Martin spy-mobile were never built at all. Who would put up with that presumptuous behavior? Not a soul, not even programmers.

In the hermetic world of AI ethics, it’s a given that self-driven cars will kill fewer people than we humans do. Why believe that? There’s no evidence for it. It’s merely a cranky aspiration. Life is cheap on traffic-choked American roads — that social bargain is already a hundred years old. If self-driven vehicles doubled the road-fatality rate, and yet cut shipping costs by 90 percent, of course those cars would be deployed.

I’m not a cynic about morality per se, but everybody’s got some. The military, the spies, the secret police and organized crime, they all have their moral codes. Military AI flourishes worldwide, and so does cyberwar AI, and AI police-state repression.

As for the spy agencies, well, Alan Turing, that mystical prophet of AI, was a spy. His code-cracking work was at the taproot of everything that has happened in AI since, and Alan Turing never once worked for privacy, user-benefit, safety, avoidance of abuse potential, or open public accountability. He had not one single trace of those modern AI virtues. If Turing had ever taken it into his head to do any of those things, he might have lost the Second World War.

Technological proliferation is not a list of principles. It is a deep, multivalent historical process with many radically different stakeholders over many different time-scales. People who invent technology never get to set the rules for what is done with it. A “non-evil” Google, built by two Stanford dropouts, is just not the same entity as modern Alphabet’s global multinational network, with its extensive planetary holdings in clouds, transmission cables, operating systems, and device manufacturing.

It’s not that Google and Alphabet become evil just because they’re big and rich. Frankly, they’re not even all that “evil.” They’re just inherently involved in huge, tangled, complex, consequential schemes, with much more variegated populations than had originally been imagined. It’s like the ethical difference between being two parish priests and becoming Pope.

Of course the actual Pope will confront Artificial Intelligence. His response will not be “is it socially beneficial to the user-base?” but rather, “does it serve God?” So unless you’re willing to morally out-rank the Pope, you need to understand that religious leaders will use Artificial Intelligence in precisely the way that televangelists have used television.

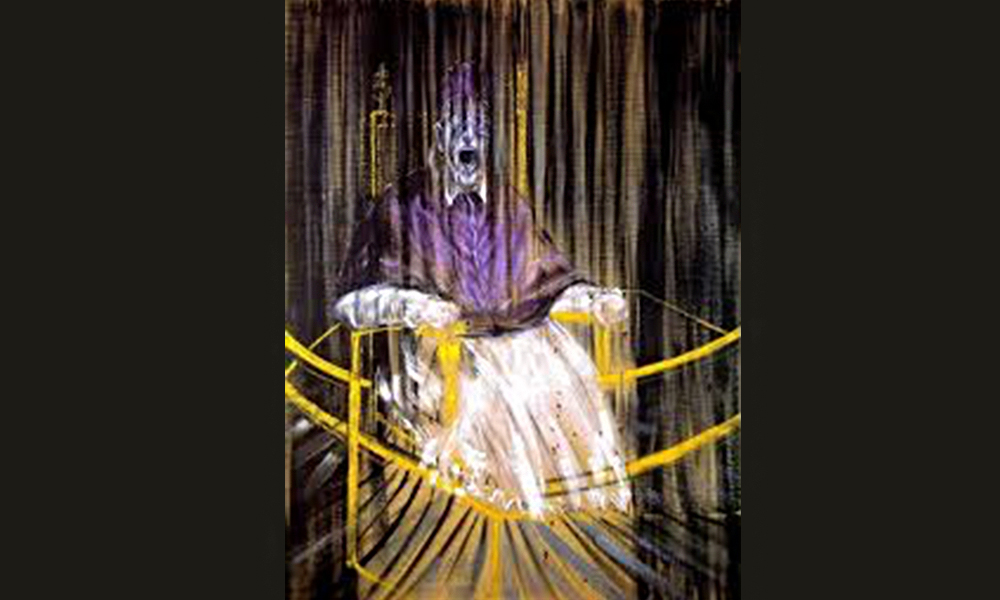

So I don’t mind the moralizing about AI. I even enjoy it as metaphysical game, but I do have one caveat about this activity, something that genuinely bothers me. The practitioners of AI are not up-front about the genuine allure of their enterprise, which is all about the old-school Steve-Jobsian charisma of denting the universe while becoming insanely great. Nobody does AI for our moral betterment; everybody does it to feel transcendent.

AI activists are not everyday brogrammers churning out grocery-code. These are visionary zealots driven by powerful urges they seem unwilling to confront. If you want to impress me with your moral authority, gaze first within your own soul.