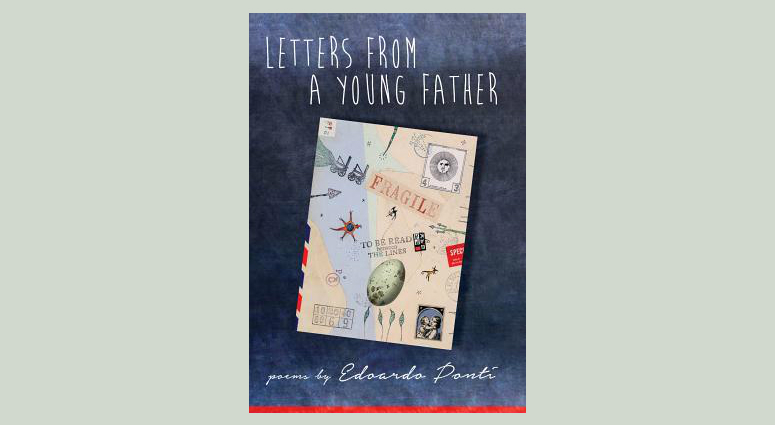

Edoardo Ponti’s first book of poems, Letters from a Young Father (2017), explores the beautiful yet anxious stretch of weeks in which Ponti was about to become a father. Letters from a Young Father captures with precise intimacy the vacillations in states of mind and emotion that accompany a new parent, as well as new glimpses of the abyss that come with such a significant life change. Ponti is a film director, the son of actress Sophia Loren and producer Carlo Ponti, though his poems arrive from a unique place of solitude, one that is apart from the hectic work of filmmaking and the glare of the public eye. Ponti’s letter-poems instill a resounding imperative that to live is to find meaning in bewilderment, that to be a poet means creating space to search through the shadowy aspects of our devotions.

¤

MICHAEL JULIANI: This book reads like a notebook kept during the 40 weeks of your wife’s pregnancy. On one hand, this form offers an inspiring constraint, with so many changes in your life impeding, and so much of the future unknown. Can you describe what it was like to create these poems and how you may have wrestled with that process?

EDOARDO PONTI: These poems were written over the course of my wife’s two pregnancies as well as the period of time between them, and, lastly, immediately following the birth of my youngest child. This has colored the poems with a combination of medias res immediacy and perspective, giving the text this contemplative quality as well as exposed rawness. These two “gears” metronome the poems and in a sense evoke their exploration of different themes. The ones I wrote as the pregnancy was occurring are more experiential, maybe more organically vulnerable, while the ones composed with the benefit of time touch more upon memory and instruction, like a blueprint to life.

There are moments in this book when you reflect very poignantly on scenes from your own childhood. Some of the poems about your father, especially, seem to have a sudden quality about them, as if the memories arrived with new energy. Could you speak to how your poetry engages with these shadowy elements of childhood?

You bask in the light of happy childhood memories but it is the more challenging “shadow” moments that define you because it is pain that traces the silhouette of the person you end up being, both in how you absorb it and push past it. Many of the poems were challenging to write because I wanted to be as accurate and honest as I could possibly be without letting judgment or residual feelings about elements of my childhood influence them. These specific poems are not meant to be cathartic but empathetic. I tried to look at my father not from the point of view of a son but of a parent. Once you become a parent, your own father’s choices take on a different resonance. It is less about forgiveness, more about understanding. It is through the prism of that resonance that I wrote these poems.

Your book dwells in a very specific period of time in which you are about to emerge from your roles as son and husband into the very new and permanent role as father. Can you reflect on how becoming a father has changed you as a poet, especially with how much fatherhood can cast new light on one’s own childhood?

In a very practical manner, fatherhood changes you as a poet by robbing you of time. It is almost impossible to dedicate three consecutive hours to writing without being interrupted; so writing poetry now has become an exercise in stealth. I try to steal as much time back by sneaking poems between school pick-ups and my day job as a director. It is not ideal but it has turned poetry writing into an underground activity, a refuge, a place I run to when I can, my own secret corner. And that made me realize how essential to my sanity writing poetry is: no matter how crowded my life is, I always find a way to dedicate face time to this fundamental part of me.

I mentioned before that this book reads like a notebook, but it is also definitely a well-refined collection of poems. How did you manage to revise these pieces into the versions we see in the book? Was it difficult to achieve that quality of breath and cadence?

As you know, all writing is rewriting because it is only when the poem exists as a physical manifestation that you can sculpt it in its intended shape. Instinct and inspiration only take you so far, the “sea worthiness” of a poem is achieved through all the work you do to it once it’s on the page. In my case, the more time passes, the freer I am from my own stifling finger-wagging judgment. Time helps me accept what I have written and allows me to shape it, objectively. In other words, I can finally hear the poem speak to me over the voice of my own inner critic. And when that happens, the process is one of subtraction. I take lines and words out, very rarely do I add anything. When you remove verses, you replace them with “creative oxygen,” you allow the reader to fill in the blank with their own life experience and that forges not only the necessary dialogue between a poet and their audience but also between breath and cadence.

I was struck by how often you address your unborn child in these poems with the hope that the child will seek the “abandon of [their] heart.” I found it very moving that you made a connection between experiencing wild feeling and finding “[t]he peace to sleep with both eyes.” How does this connection resonate with you on a daily basis?

The challenge is to have as little daylight as possible between what you want and what you need. What separates the two is ego. Ego is the firewall between you and your potential because you can’t build anything solid, durable and sustainable listening to the needy voice of your ego, or “childish heart,” which is the ancient Chinese word for it. The secret is to find the volume dial to your childish heart and turn it way down, for it is maybe impossible to switch it off completely. Every day led by your true compass is a day you can honestly call your own.