The first time I saw Olga Livshin she was passing by the window of the studio I was working in. It was raining heavily. She was carrying a brown carton and talking animatedly on her cellphone. Five minutes later, she passed by my window carrying a stack of books, still talking on her cellphone. We were at a writers’ residency in Virginia and, I deduced, she was moving into the studio next door. We would be neighbors. She went by a third time, a cup of tea in one hand, still talking.

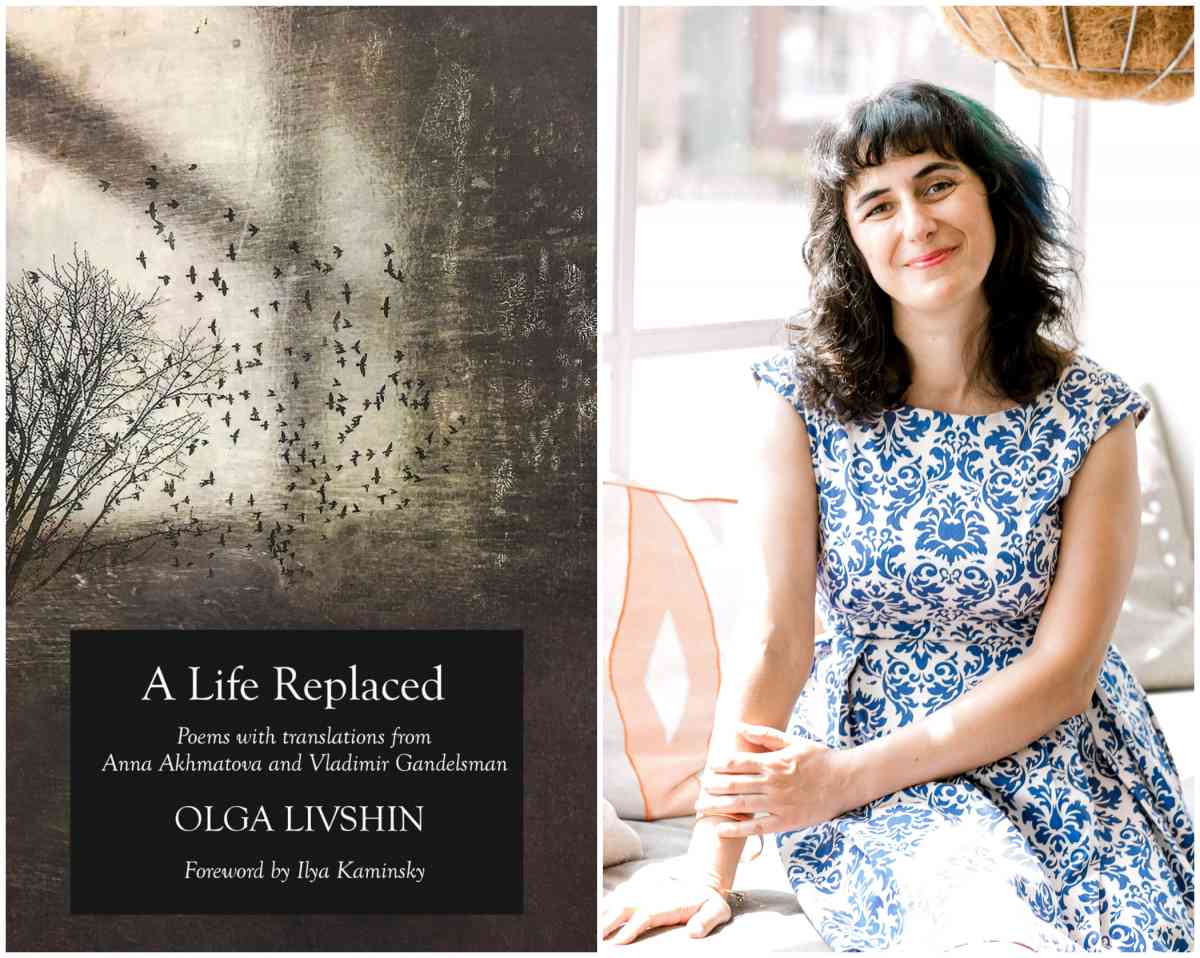

Livshin is poet and translator, multi-tasker and rapid-fire talker whose words can be read in her newly published book of poetry, A Life Replaced (Poets & Traitors, 2019). This slim volume weaves Livshin’s own poetry through her translations from Russian of work by Anna Akhmatova and Vladimir Gandelsman. In doing so, Livshin grapples with her own life as an immigrant, her childhood in Odessa, and her life in the US, where she lives today. As a translator and immigrant, Livshin’s work particularly resonates for me. We reconnected on Skype last week, she in her home and me in my office in the Ella Valley of Israel.

¤

JOANNA CHEN: How did this book that straddles two languages come into being?

OLGA LIVSHIN: It goes back to something that most children of immigrants share when they move to another country. I think the original language is still a little bit like the mother’s milk and then the second language is something like Coke — delicious and fizzy but not ultimately as fulfilling as what they’re used to.

You were 14 when you arrived in the US from Moscow.

I think, like most immigrants, I veer between two languages, two cultures. We are in the process of translating our own lives in our heads, where one part of us is hidden.

I dealt with my own culture shock at that time by translating poets that I really liked, beginning with a contemporary poet, Nina Iskrenko and then, in college, I gravitated toward one of the authors who came to be in this book, Vladimir Gandelsman. I absolutely think of my relationship to his poetry as an apprenticeship.

I think where it differs from Akhmatova is that, for me, Akhmatova’s poetry is like swimming in an endless but still — controlled-waters, whereas Gandelsman’s work is full of linguistic surprises: images that connote dark humor, interruptions of one register by another (i.e. lofty poetic diction by conversational languages and back), and dissonant rhymes. His poetry challenges, and I like being challenged by it and hopefully incorporating some of its features into my work.

Do you remember the first time you wrote a poem of your own in response to another poem?

Anna Ahmatova has always been looming over my world as a seminal figure; as Ilya Kaminsky says in his foreword to my book, she is “the great poetic mother.” Akhmatova is pictured in all these portraits as an arrogant poet who doesn’t look you in the eye, who’s posing, she has this long shawl, and I always found that intriguing because the more people create these layers around them the more likely they are to be actually vulnerable inside. Her poetry is quite steely and impenetrable, deceptively simple, but actually there is a smaller and more vulnerable self, and when I taught a class on her, a few years ago, in Alaska, I read some biographies about her, and I got to know the hardships and also the love affairs of this woman, and the difficult childhood she had. She came from a family where the father was away and cheating on the mother and eventually they were divorced, and these experiences shaped her. And so I realized that this posing as a poor Russian old lady with gorgeous hair was a kind of armor she created around herself and when there’s an armor I guess it creates an instinct in some of us to go after people who have armor and to undress them and see what’s underneath the armor and to say — I am like you and you don’t have to do this, I see this and I understand why you had to do this.

Is this when you first wrote a poem in response to Akhmatova?

Yes, my first poem in this book dedicated to her is “Annas at the Stove” before I even had the idea for this book… and I thought, My goodness, we think of Akhmatova as the strong feminist — and she is — but she also had to live through self-destructive acts such as burning down the library and works of a loved one. What did that feel like? And then I reread her poems through those eyes and write my own poems, addressing Akhmatova.

I think a lot of the work of a translator is a very deep reading of the text as you have just said — the armor, the undressing, what lies underneath. Isn’t that what we do as translators?

It’s one of our many odd jobs as translators, including this imposed striptease. I first got this when I read an interview with Tatyana Tolstaya, the contemporary Russian writer. I don’t remember the exact image but it was about navigating other people’s souls, it was about a hankering to understand very deeply and very closely how another being breathes and walks and I think it comes from a certain impatience with the liminality of life, of one life, and wanting to live more than one lifetime, this fantasy, right? It’s not realizable but we at least try on other people’s selfhoods. We can be male, we can be of another era, we can be collective, as when one translates an epic poem, we can move to other places. So absolutely, I find that it’s a kind of travel.

There’s this stripping off, but it’s also about listening to voices very deeply. This comes out in the intertextuality of your book, your own voice responding and interacting with the two poets.

I think it’s so fascinating that you’re bringing this up, the interactions that happen in life experiences, in cultures and history, and it just occurred to me that this book is in English, not just because of the practical reason that I’m addressing an American or at least English reading audience, it’s also that this book establishes some kind of idea of a common language that doesn’t really exist in principle, right? We each of us speak slightly differently, not even an idiolect, but a language of a self that is not fully comprehensible. We are mysteries to each other and I really like the idea of what it would be like if we could try to see another person as fully complete, in all their glory.

In “Dressing a Memory” you write, “Well, these are child words: / Моя радость, a lantern on some other life.” It’s a very rich line. A lantern not just on some other life but a life from another place or time. On the other hand, you say “child words,” so it could be your childhood as well.

I wrote that poem before becoming a mother and now, having seen my own child communicate in a way that’s not verbal, it’s interesting to me… there’s trust that happens before words are formed, and I think it’s that part of language we keep seeking our whole lives. We want to be understood and appreciated in exactly that way by others, we want to have agency in the world, to define… Language breaks down. Language is an imperfect medium as we know. Just because it doesn’t work doesn’t mean we shouldn’t stop trying. I dream of a world in which, for example, immigrants get to define some of the agenda for how they are seen, outside the narrow ideologies into which they are squashed. A world in which various marginalized groups would have some kind of say in the respect that is due to them and in the way that their cultures and languages are honored. I see that breaking down all over the world right now. It’s very disheartening to see. We want to have some kind of agency, some kind of role in defining the agenda for how we are seen in the world. obviously our actions matter too but trusting the world, the idea that we’re not like I say in one of the poems just “murderous strangers,” it would be very nice if that were the case.

Isn’t translation very much a lamp on some other life?

So I think yes, translation can be that lantern. I think what’s going on in this poem is another dream of language without language, language without translation, that the two lovers, who might have been totally incidental to each other, might have touched each other literally and metaphorically in a way that somehow left a mark on their lives. And so that is not unlike the childhood language we were talking about earlier. I think translation attempts to do that, I think that translation also probably fails in a myriad of ways because we can’t translate somebody without adding something. So rather than making it some kind of pure correct translation, actually what we produce at best is a kind of touch, the impression of how somebody touched us and why, how that author affected us when we were reading them. At best, as translators, that is what we carry. We actually carry our fingerprints all over the finished product. We carry the author, we carry ourselves, it’s not a pure effect at all.

Do you regard yourself more a translator or more a poet?

For me, poetry and translation come fundamentally from the same place. I think they momentarily put a little patch on the holes that language leaves. And by language I mean everyday language. We do a lot of harm with accidentally said words and these days these words stick around because of social media, people cause harm through imprecise language, language that creates cruel actions. The use of language and imagery, whether its poetry or translation, someone else’s words or mine, language and imagery that trickle down into the heart, we translators can do a little bit of damage control.

In this way, translation is also a lens into another world.

Yes, I think that is beautiful, translation as a kind of lens in which to look at the world. You can’t get this by only reading yourself or the same five poets you read…With translation I agree that there is a sustained, close way of interacting with the text that you don’t get elsewhere. You live with that text, right? I guess for me writing my own work is important because I do feel like my Russian is censored or rather sent to its room because it’s been bad. And so for me, even when I write in English, it’s as if I am writing in Russian because I’m releasing something that was the first fourteen years of my life, it’s like I carry this genie inside me and I need to let it out occasionally. Let it walk around a little before I bottle it back up.

Do you write in Russian?

No! I gave up on writing in Russian. So there is not a lot of self-censorship but there is an audience that I address. I live here [in the US] and this is where most of my community is and this is where the people that I want to speak to are. But actually I can’t speak to them the way that want to. So every time I write it is a translation from the original.

Mother tongue!

It’s very personal isn’t it? We appropriate it for a particular thing and then that thing becomes us, who we are. The voice is very much in that language, in the maternal language, for both you and me. that voice wants to talks and wants to be heard.

Immigration is a strong theme in your book. In your introduction, you describe how you were attacked in your first year at junior high in San Diego. You were different, you looked and acted different.

It’s not like xenophobia began yesterday. I found it very odd when I came to this country that it was ostensibly such a multicultural society but when you got to know people, when you spoke to them, they were more interested in your gratitude to be here and how now you’re an American teenager so there’s an implicit push of assimilation into the melting pot. And to me that in itself was rather crushing at 14. But, you know, I survived and am probably stronger for it. For these kids who are detained [today] it’s unimaginably cruel and, you know, like everyone else I am frantically watching the news and this nightmare. There are many ways to help.

Right now it’s extremely difficult to look at what’s going on and, when I began writing this book, the forebodings of it were there and Trump got elected. It’s a question of what can poetry accomplish and what can translation accomplish. There are now several great literary groups that have events to try to donate some money to migrants… I’m not part of those groups, I’m a busy mom who teaches. But I started a reading group in Philadelphia with my friend Julia Kolchinsky Dasbach for refugees and immigrants, descendants of immigrants and Americans who care. I believe in visibility and in voice; there are many ways to help.

I’d like to end with a really beautiful line from one of your poems: “And her husband texts her Come home and she types Where’s that / And he texts her With me.” So what is home?

I think that the word refuge is relevant here because when we talk about home it seems like something that is warm and permanent but refuge is a more realistic idea of what we can create for each other. As a person who’s moved all over the US, as well as from country to country, I’ve come to really appreciate the validity of refuge. It appears in the first poem of my book, “Translating a Life”:

Unfortunately, I care. And, sitting here

by a huge flowering bush, I see no refuge.