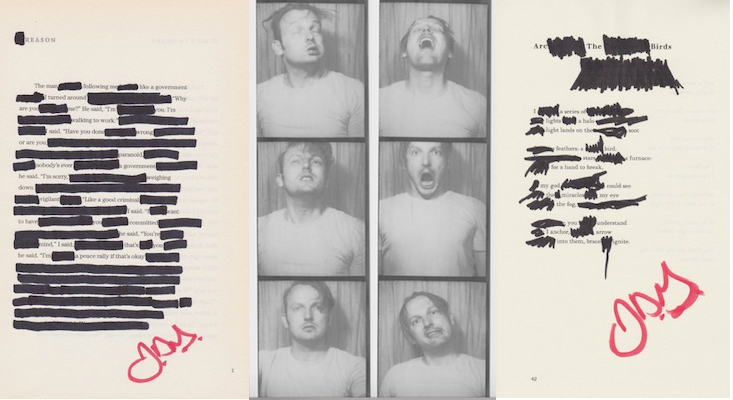

John Gosslee is the author of Blitzkrieg, an interdisciplinary work of poetry, essay, and art project. I recently had a chance to ask him a few questions about erasure poetry and his new book of blackout poems, Out of Context, which was just published by Press Otherwise.

¤

KRISTINA MARIE DARLING: Your book showcases the tremendous range inherent in erasure poetry. At times, erasure becomes a critique or a parody of the source text, and in other instances, erasure serves a means of redirecting the focus of the reader’s attention, prompting them to focus on something that they might have otherwise overlooked. You also reveal erasure as a way of making a text strange, of recontextualizing. Could you speak about how and why the various texts you engaged with warranted different modes of engagement?

JOHN GOSSLEE: The project was multiplicitous, in that I attempted to include poets that have both achieved a certain level of cultural currency and employed a large range of approaches to voice in their work.

When I redacted a portion of Gabriel by Edward Hirsch, I cried. The love of a father for his son was so moving that I couldn’t help it. I thought about how I might feel in Hirsch’s place if I knew about the redaction of such a personally meaningful text. I thought about how I’d feel as a reader if I only knew about the redaction 50 years after Hirsch, and that helped me hold to the goal of the project, which was to pick living poets who I might say are “popular poets,” though those two words seem contradictory.

It was important to redact poems that really moved me and important to redact those that didn’t move me at all. In my mark making, I treated all of them with an automatic emotional response.

There’s another “why” too, which is that I wanted to reclaim emotional territory from poets who I felt occupied space within myself and in the external world. My relationship to that occupation, to the ways in which it both authorized and threatened my own capacity to express, is manifested in these erasures. I think of my relationship to those living poets who are rightly heralded as today’s greats the way I think of a sequoia: a sequoia is beautiful in its grandness, but that same grand canopy prevents saplings from growing. It’s not the intention of the sequoia to swallow resources and light, but it does. For me, redaction was a way of claiming a space in which to breath spiritually and creatively.

There is also a great deal of variation in the visual presentation of the work. In some poems, the markings of erasure make the text appear almost as code, as encryption. In others, there is a violence to the physical act of erasure, while others seem almost playful in their redactions. Why did certain texts call out for a different visual presentation than others?

The different styles of marks were real acts about how I felt about the poem and my feelings are multitudinous. Because I was determined to make only a single pass at each poem, each erasure is an artifact of how I felt at that moment. It’s an objective expression of a very subjective moment. I’m sure that if I was to do the project again, which I never will because of its scope, it would all turn out differently.

As readers or artists there is some work we love, some work we hate, and there is a bit of work on the periphery that we struggle to remember because it doesn’t elicit a strong response. I wanted complete, unbridled transparency between myself and the work. Work that didn’t resonate got more marks, which held less of the original work, while work with which I was somehow more engaged elicited more creative, script like marks.

Truthfully, I also started getting bored toward the last quarter of the project. I redacted 333 poems! Boredom drove my exploration of mark making in that last quarter.

The poems are signed as though they are works of art. Although the movement between poetry and visual art is often fluid, where would you situate these works? What sparked your interest in creating dialogue between poetry and other mediums?

I’m interested in collaboration across different types of media and I’m interested in at least attempting to be original. I recognized that by signing each of the pieces and presenting the original pages as the completed pieces rather than retyping them for a kind of uniformity, I privileged the act of creating, which revealed the creating hand itself. That’s what interests me in art. The cutout, or the redaction itself, is nothing new, but in my research, this type of presentation is new.

Many people conceptualize the act of erasure as textual violence. As an individual who arguably occupies a position of privilege, how do you work against this perception of erasure as an act of destruction?

It was very important to me to cite each of the original authors and the original work as the title of each piece to invite readers to explore the original. It’s important to keep in mind that I was redacting one of thousands of copies of a text, not the sole text. In some cases, I was redacting people who I respected and know, and in other cases I redacted people who I knew, or didn’t know and therefore couldn’t actually care that I existed. In a case or two, I redacted people who I know don’t like me and there was a pleasure in that too.

What are you currently working on? What can readers look forward to?

Analog, a small book of poems, chemical photo booth pictures, and literary magazine brands that just came out. I’m excited to start working on another project in the next two years that incorporates the names of dead soldiers from each U.S. war starting with World War I through our present day. The top 10 corporations and 10 richest people of each year of each year are spelled out of the soldier’s names. It feels like a natural progression, it also feels like something that is actually important and holds real weight. The redactions were cathartic and the new project continues the experiment of the removal of value by adding or exposing another kind of value, which is the question originally raised in the redactions.