For the past nine weeks, Hong Kong residents from all walks of life have been taking to the streets in record numbers. The largest of these increasingly frequent demonstrations saw roughly 2 million people — about a quarter of the territory’s population — march peacefully to protest a proposed extradition bill that would allow anyone in Hong Kong to be sent to mainland China to face trial if accused of certain criminal offenses. Mainland courts are notoriously opaque and subject to pressure from — if not outright control by — the Chinese Communist Party. Many in Hong Kong, from lawyers and civil servants to taxi drivers, shopkeepers, and students have been deeply alarmed at the prospect of a law that would remove a legal protection that is crucial to Hong Kong’s independent judiciary. At present, Hong Kong has no extradition agreement with Beijing.

The territory is no stranger to demonstrations. In 2003, some 500,000 people came out to protest a proposed national security law, which many feared would make it easier for the authorities to stifle dissent; the legislation was ultimately withdrawn. In 2012, tens of thousands of protesters, many of them in secondary school (including Joshua Wong, leading a movement for the first time then, while just in his mid-teens), surrounded the government complex for 10 days, demanding the government drop its plans to implement a nationalistic “Moral and National Education” school curriculum that praised the Communist Party of China and criticized democratic movements; the curriculum was abandoned. Then, in late 2014, the student-led sit-ins and mass demonstrations that came to be known as the Umbrella Movement brought parts of the city to a standstill for two months. Protesters demanded reforms, including the direct election of the Chief Executive; but this time, the government did not accede to the protesters’ demands and kept the status quo. (For a discussion of both the 2014 protests and the current situation, which approaches the events via the songs used by crowds, see Alec Ash’s recent essay “Singing for Hong Kong.”)

As a result, Hong Kong continues to be governed by a Chief Executive handpicked by Beijing: nominated and elected by a 1194-member Election Committee dominated by business and other constituencies sympathetic to Beijing. (The upshot of this is that both the Chief Executive, as well as many representatives on the Legislative Council, are elected by a bloc whose views do not reflect the popular will. Neither current Chief Executive Carrie Lam nor her predecessors would have occupied that position had the choice been brought before a popular vote. This situation might feel uncomfortably familiar to voters in California and other populous states in the US, whose votes in national elections are greatly diluted by the Electoral College. Indeed, the Election Committee has been compared to the Electoral College — but Hong Kong’s Election Committee also gets to control who is even allowed to stand for election to the top spot.)

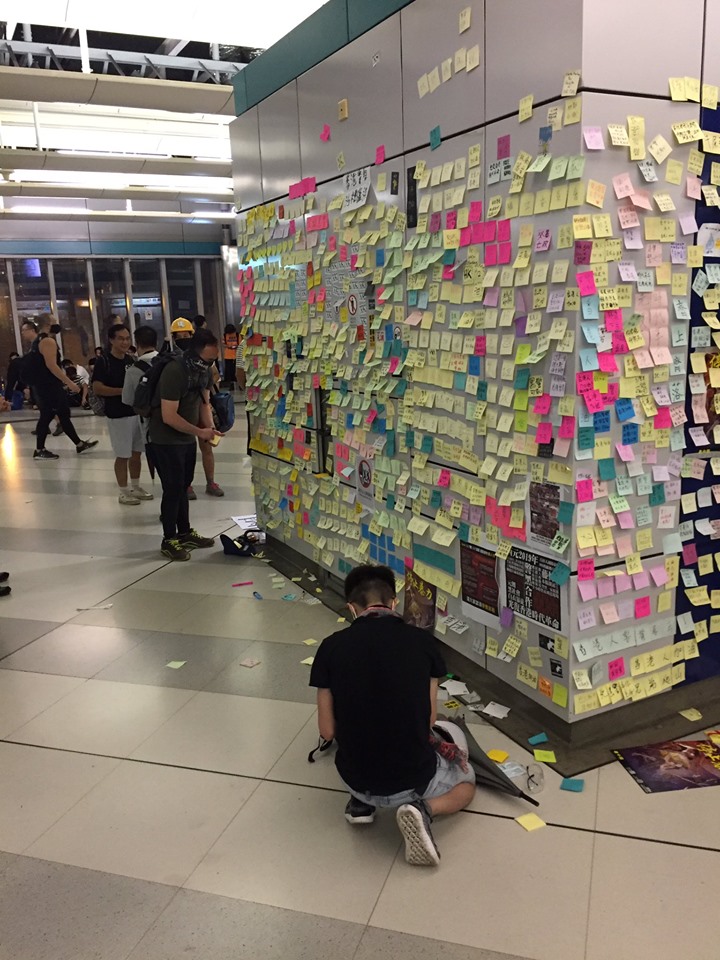

Tellingly, one of the first important collective actions in the anti-extradition law movement was a June 6 silent march by a group of 3000 lawyers, who ended their workday by protesting the threat posed by the bill to the rule of law in Hong Kong. This was followed on June 9 by a march by 1,000,000 people. Demonstrations large and small, often organized on secure messaging apps, sometimes openly publicized and sometimes not, have cropped up on weekdays as well as the more traditional protest days of Saturday and Sunday. Lennon Walls — where citizens leave multicolored post-it notes inscribed with their hopes and dreams — have also appeared in numerous public spaces.

The government response has only served to escalate matters. Rather than treat the widespread public outcry as valid, Carrie Lam initially took a patronizing attitude, which segued into arrogance and willful disregard for public opinion. She has now all but vanished from public view. Meanwhile, Hong Kong’s police force, once widely respected for its professionalism, has resorted to increasingly militaristic tactics. There have been numerous, documented instances of the use of excessive force: rubber bullets have been shot, pepper spray sprayed, truncheons deployed, and tear gas cannisters released over and over again.

Although the extradition bill was the issue that united much of the public in opposition, the government’s unwillingness to withdraw the bill (only to say that it will not be considered just now) and its backing of police actions has led the populace to expand their appeals to include demands that Lam step down, calls for investigations into increasingly frequent instances of police use of excessive force and police complicity in attacks on protesters by thugs, democratic electoral reform, reclassification of protests to remove the label of “riot” applied to some crowd actions, and the dropping of charges against some demonstrators.

While the first massive demonstrations were striking both for their size and for the peaceful and orderly way in which they were conducted, and most demonstrations have continued to be nonviolent, small contingents of mostly young protesters, often after hours, have engaged in scuffles with armed police clad in riot gear, hurling water bottles and bricks at police. Demonstrators have broken into the Legislative Council building and left political graffiti on the walls. They have defaced the national emblem of the People’s Republic of China as well as that of the city. Significantly, violent episodes like the storming of the Legislative Council building have not been widely condemned by the public. On the contrary, a number of older people, office workers, and retirees have told journalists that while they do not necessarily agree with such actions, they completely understand why these young people felt compelled to carry them out.

Earlier in the summer, it was fairly easy to keep track of events, but the pace has been accelerating. For the people of Hong Kong, who are bearing witness to the movement on a daily basis and whose futures will be determined by the outcome of the conflict between citizens and government, the situation is becoming increasingly fraught. But apart from joining protest marches, how can people there respond to this crisis?

One Hong Konger, Tammy Ho Lai-Ming — poet, scholar, and president of PEN Hong Kong — has also been active in the current protests. But for her the situation has also demanded a more personal response. Since mid-June, she has been writing poems with her reflections on various events and posting them on Facebook. Taken together with journalistic reports and social media feeds documenting events, these poems make up a complementary timeline. Six of Ho’s poems are republished here.

By the time you read this, there will have been more demonstrations, possibly more altercations, and Ho will likely have written more poems in response to these events. But for now, let these poems record where things are today.

¤

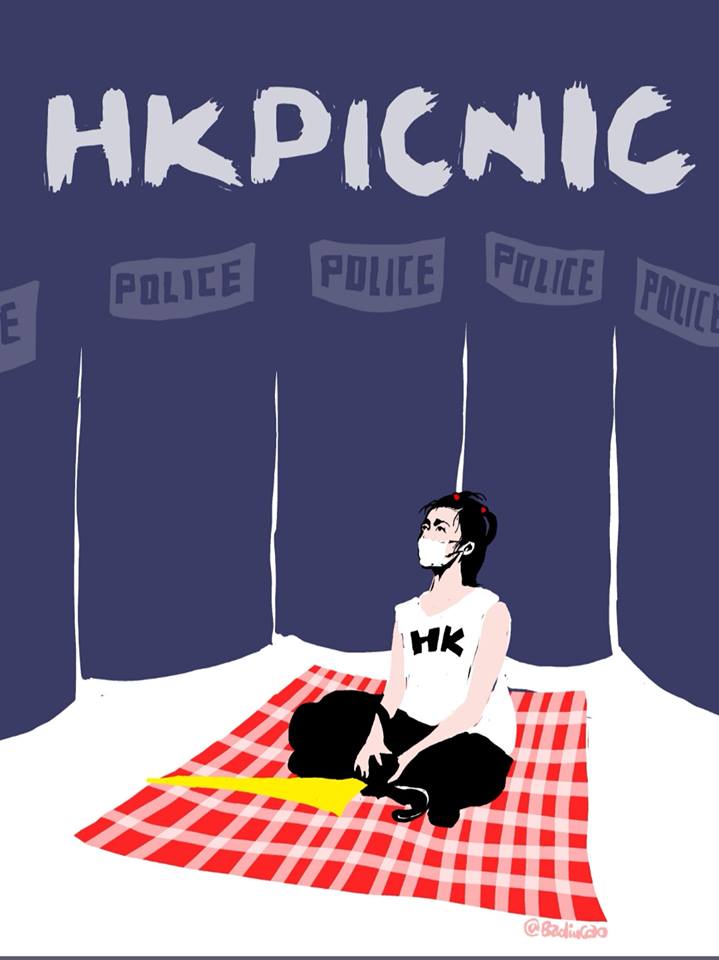

This first poem, “Some People,” is accompanied by a political cartoon by free-speech activist and artist Badiucao, entitled “Hong Kong Picnic.” This cartoon was inspired by one of the protest organizers’ many creative strategies. If they were denied a parade permit for a daytime demonstration (which was a concern), the protesters were going to show up at a designated time and place with picnic blankets. After all, there are no laws against picnicking in the park.

“Some People”

— Tammy Ho

Some people shed their petty personalities like snake skin, only to grow a new layer that is a strengthened version of the old. On the other side of the river, it is no longer the same river — some people accept this as fact, others secretly question it because they don’t understand. One week always flows into the next and a chorus of international cameras can’t reverse time, can’t change some people’s minds. Some people take turns to bleed for what they think is worthwhile. There are those who succumb to flattery, delighted at being called intelligent, having a good poetry ear and perfectly timed. There are those however who loathe praise, every hyperbolic word is perceived as a carefully constructed insult. In a neat room no one is foolish enough to throw the first piece of trash on the floor. In an already tarnished room, some people readily fantasize smashing its glasses and concealed windows. When some people find out they are in a novel, they demand to be given the ability to create tears, to genuinely cry. Some people sell lies. Some fabricate them as though in a party line. Some live in lies like living in a sealed showroom. Some people look on. Some take action.

Image: “HK Picnic” by Badiucao, posted June 13, 2019.

¤

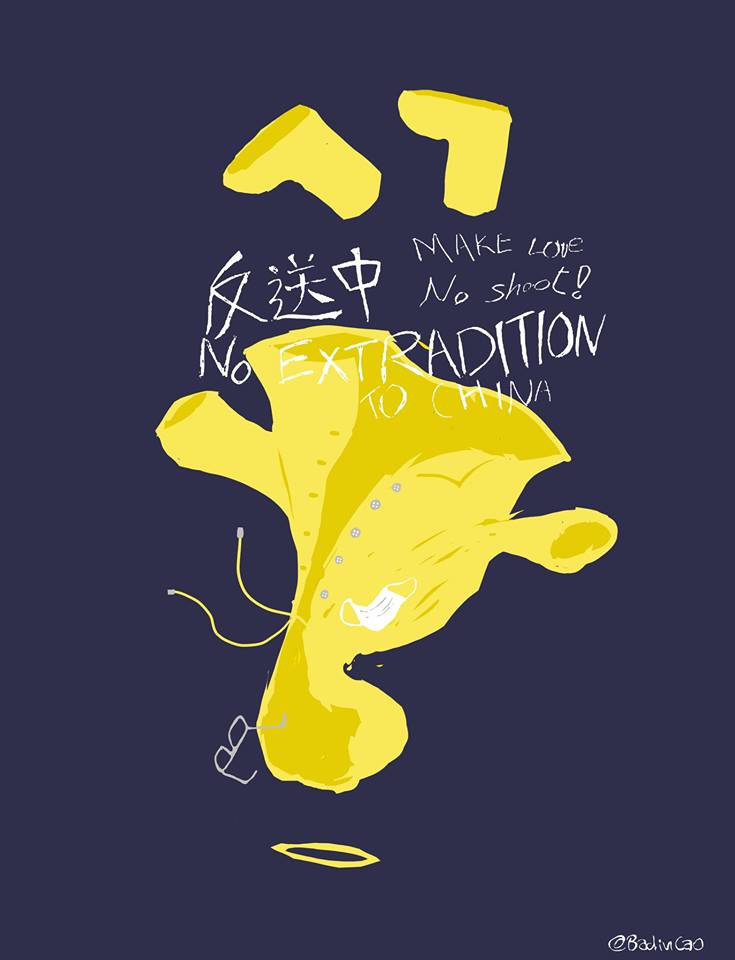

“The Fall”: On Saturday June 15, on the eve of the second mass march, a man surnamed Leung jumped from a shopping mall in the Admiralty District. Before he killed himself, he had unfurled a banner. Ho incorporated the words on the banner into the following prose poem. The palm is both an elegy for Mr Leung as well as for the poet’s fellow citizens, should they fail to achieve their goals.

“The Fall”

— Tammy Ho

A note of demands on behalf of the whole city that has been battered, tortured, frustrated by the inhumane and tone-deaf government of Hong Kong: “No Extradition to China. Make Love No Shoot. Total withdrawal of the extradition bill. We are not rioters. Release the students and injured. Carrie Lam step down. Help Hong Kong.” What must have gone through his mind as he fell? That he was there, and then he was no more. What does it say about a city that drives one of its own literally off a building, in public sight? We have tried and tried to make our voices heard. Some sing hymns. Some forgo food. Some make signs. Some cry in silence, trembling, nursing a lingering heartache. Do we all have to imprint notes across the city, on its mountains and bridges and lampposts and shop fronts and park benches and walls, for us to be finally heard? The bell tolls for us all.

Image: “Falling Man” by Badiucao, posted June 15, 2019.

¤

“We Are What We Are Made Of”: The following poem notes the creation of the first Lennon Wall (“walls are covered in squared colours”), the strategy of being “like water” (“million faces, million thoughts, / united in water”), and it concludes with a challenge to the authorities, stating that the citizens of Hong Kong have become a force to contend with and are not going to give up. The following image, taken from Ho’s Facebook page, shows the sign for Causeway Road, which has become Go Protest Road.

“We Are What We Are Made Of”

— Tammy Ho, July 25, 2019

Beginning from every day

tears are shed: their tails are puffs

of smoke. Beginning from yesterday

walls are covered in squared colours,

street names changed. Beginning from then

poetry can mean, be, and stay. Beginning

from June 2019, people

in a city look at each other:

million faces, million thoughts,

united in water, practice, slogans.

Beginning from now,

there is no turning back, no stopping.

We are what we are made of:

desperation and unbeatable will.

This is the beginning of the open

secret that we don’t ever quit.

Image: Altered street sign via Yuen Chan on Twitter.

¤

“The City I Live In”: This poem evokes the transformation of Ho’s city from a place of glass fronted office towers and high end boutiques to a place of diverse bodies acting in concert. These demonstrations have been notable in that they are “leaderless.” This public mobilization has been operating as a sort of collective, rather than as a hierarchical organization.

“The City I Live In”

— Tammy Ho, July 27, 2019

On weekends, people walk the streets in the fierce sun

on the brink of fainting—

grey sweat comes down to their ankles

when a river of heads chants add oil.

At least one in seven people choose to boldly speak

a forbidden language of signs, posters, and videos;

of hope, metaphors, malls, and proliferating

Lennon Walls. The city I live in is no longer

only office buildings with glass fronts

or identical shops that sell identical

things. It is a city of diverse limbs

that each know their direction—

wherever they are needed, they go.

Image: “Lennon Wall now inside Yuen Long Station.” via Austin Ramzy on Twitter.

¤

“This Moment”: On the last weekend of July, a Cathay Pacific pilot on the final approach for landing at Hong Kong international airport was recorded over the PA. After providing routine information, such as the local temperature and time of day, he begins to talk to his passengers about a sit in that is taking place in the arrival hall. He urges the passengers not to be alarmed by what they see, because the demonstrators are peaceful, and he encourages people to speak with the demonstrators, so that they can learn more about the situation in Hong Kong. He concludes with a few words in Cantonese: “Pour it on, Hong Kong people! And be careful out there!” He uses a common Chinese exhortation, literally translated as “add oil” (meaning, in essence, “Go!”), which people sympathetic to the protests have widely adopted as a way to encourage the people of Hong Kong to keep on resisting and keep pressing to have their demands met.

The audio clip can be found here.

“This Moment”

— Tammy Ho, July 28, 2019

At this moment an airplane is landing. The pilot

makes the usual announcement

before explaining to passengers about the peaceful

protesters at the airport dressed in black.

He switches from English to Cantonese

to say the most heartfelt words.

At this moment a family is going to Disneyland.

A little boy is oblivious to teargas and rubber pallets,

thinking only of Mickey Mouse and Winnie the Pooh.

May he grow up to never know

the fear of being caned.

At this moment

train stations are transformed into battlegrounds,

blood of citizens on floor

like abstract calligraphy. The trains

take no one to nowhere until someone

makes some right decisions.

This moment a people is angry. They carry

on with their lives barely. How many more

days to endure for a government to listen

and show remorse?

At this moment, everyone is a revolution.

Image: Hong Kong International Airport arrivals hall, via Tammy Ho’s Facebook page.

¤

“Anecdotes for The Future”: By the last day of July, the first typhoon of the season was close enough to Hong Kong to bring high winds, heavy rainfall, and disrupt air traffic. Ho conflates the threatening storm with a drive-by attack on the crowd outside a police station. Attackers in a speeding black car shot fireworks directly into the crowd, causing a number of injuries among the assembled protesters.

“Anecdotes for The Future”

— Tammy Ho, July 31, 2019

1.

Sometimes a typhoon

is not just a natural phenomenon.

It coincides

with a movement.

2.

They would claim

they are not tyrants,

only realists, patriots.

3.

Dark night. Fireworks horizontally

deployed from a moving black car,

weapons with ringing sounds

and colours. Smoke

gets in the eyes of protesters

in the town where I grew up.

4.

A gun’s mouth can point

Middle fingers of the police

are raised

All that is steel or sturdy

can become youngsters’

makeshift shields

Our full bodies are alert

5.

Near dawn, strangers

in their separate rooms, on different

sofas or looking out of their myriad

windows, collectively sigh or cry.

6.

The disobedient citizens

are determined to be,

to be disobedient,

in all parts of the city–flowers

blossom everywhere. All

walks of lives, all hues of hair,

cut open our regular existence

to forge a new Hong Kong.

Image: Apple Daily. At around 2:30 am on July 31, 2019, fireworks were shot from a moving vehicle at people protesting outside the Tin Shui Wai police station.

¤

The events in Hong Kong continue to unfold at a very fast pace, with new changes everyday. One of the best ways to keep abreast of them is via the invaluable Hong Kong Free Press website. If you are on Twitter, you may also want to follow the feeds of journalists and commentators who have been and in some cases still are on the streets, such as, to name just a few, Elaine Yu (@yuenok ), Mary Hui (@maryhui), Austin Ramzy (@austinramzy), Isabel Steger (@stegersaurus), Louisa Lim (@limlouisa), and Antony Dapiran (@antd). You will also, of course, want to follow at least one poet: Tammy Ho Lai-Ming (@myetcetera).