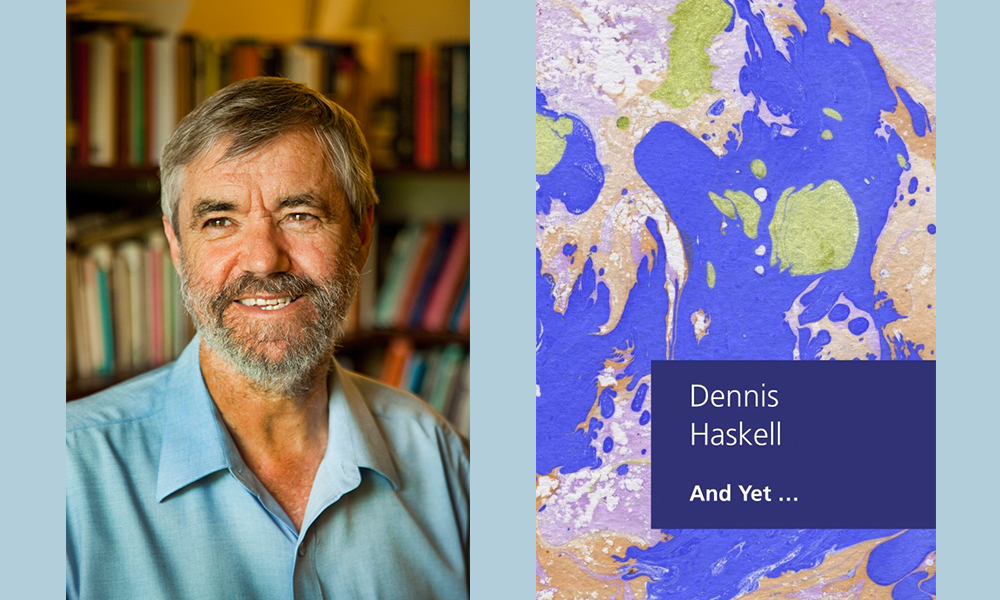

Dennis Haskell is the author of nine collections of poetry — the most recent And Yet… (WAPP, 2020) and Ahead of Us (Fremantle Press, 2016) — plus 14 volumes of literary scholarship and criticism. He is the recipient of the Western Australia Premier’s Prize for Poetry, the A. A. Phillips Prize for a distinguished contribution to Australian literature (from the Association for the Study of Australian Literature), and of an Honorary Doctorate of Letters from the University of Western Australia. In 2015 he was made a Member of the Order of Australia for “services to literature, particularly poetry, to education and to intercultural understanding.” He is Secretary of the Perth Centre of International PEN. His website is dennishaskell.com.au

¤

AMY LIN: You are known for your light touch with rhyme, and manage to skilfully use rhyme and half rhyme — particularly at the end of your poems — in a way that is subtle yet impactful. How do you see the role of rhyme, both in your poetry and in contemporary poetry today?

DENNIS HASKELL: When I began writing poetry in the 1960s, rhyme seemed antiquated. In my first book I don’t think I used rhyme at all, as most poets don’t today. In the last 25 years rhyme has made a bit of a comeback; it’s interesting but difficult to speculate on why this has happened.

One of the features that distinguishes poetry from prose is its greater tunefulness. Poetry is generally much more musical. Rhyme potentially has a great role to play in this. I love music, although one thing I’ve learned over the years is that the music of language is very different to the music of music. I love exploring what can be done with the musicality which rhyme, in all its manifestations, brings. In some poets’ work — Tennyson, Verlaine, early Yeats — as much is said through the music as through the direct meanings of the words.

I think contemporary poets don’t pay enough attention to the possibilities that rhyme, and other features of traditional verse, offer. That said, a contemporary poet has to handle rhyme with care, unless writing children’s verse or comic verse. We are surrounded by pop songs and advertising jingles in a way that Shakespeare, Pope, and Christina Rossetti weren’t, so rhyme, especially strong rhyme, can easily sound trite.

Perhaps related to rhyme is humor. Many of your poems are light-hearted in tone and spirit, and have a distinctly Australian comedic flair. How do you find the process of writing humorous poems, whilst still retaining a semblance of seriousness and emotional gravity?

As with rhyme, I think there’s not enough humour in contemporary poetry. Ever since my first book I’ve tried to include some comic poems, and even in the first one, Listening at Night, there were some comic elements. They are fun to write, and sometimes a challenge (which is part of the fun). If poetry is ever to gain an audience of general readers then it needs to have some sense of fun.

The old adage that comedy is close to tragedy is undoubtedly correct; it’s often the stance we take which determines which mode we’re dealing with. The slip on a banana skin is comic if it happens in a formal situation and the person is not hurt, especially if the person is rather important or pompous; it’s not funny if he or she is a pauper and tears an Achilles tendon. The tone of a poem has to “tell” the reader which mode we’re in. Not far below the surface of my comic poems is the possibility of seriousness, so retaining a degree of emotional gravity is in fact difficult to avoid. Australian comedy is notoriously hard-bitten and sarcastic, and my poems might reflect that — I’ve never stopped to consider it.

Kenneth Slessor is an important poet for me and for a time he wrote comic poems every week in his work as a journalist at Smith’s Weekly. In them, and in his serious poems, he used rhyme brilliantly.

On the other hand, your latest collections are marked with poems of grief, particularly the loss of your wife Rhonda, as well as other losses of family and friends. What part does poetry play in your grieving process?

After Rhonda died I wrote a number of poems about, I carefully say, my experience of her experience of cancer and death from it. They were collected in my book Ahead of Us, and there are others, different in tone (less angry, more resigned), in my recent book, And Yet….

Michael Cathcart of the ABC interviewed me at the Margaret River Readers and Writers Festival, and the interview was played on his Books and Arts programme. He asked me why I wrote such poems — a question that had never occurred to me. I replied that it was just what I do, which is an honest answer. He also asked why I put myself through the process of writing and being interviewed about it. I said that I would do anything to publicize the situation around ovarian cancer and that anything I went through was nothing compared to what women who get the disease go through. This is also an honest response, but I’m sure the full answer lies much deeper than that.

People like me are just words people — I have no idea why. I grew up in a working class environment, in a house without books, and yet I was always a reader. I feel totally comfortable in and around words, and I think that was just born in me. So turning to words at strong emotional times is natural. Words are the principal way we deal with everything, so it seems natural to explore and to expiate those terrible experiences through them. Death is one of the two great subjects of poetry (the other being love) and it is poetry which gives the deepest responses to them.

When the program was broadcast on national radio I received emails from people all over Australia who had gone to the trouble of tracking me down. Some described having to pull off the road when they heard the poems being read, one doctor told of reading poems to patients. That was so rewarding, better than any book review.

Freud said that all art was therapy, and I think he was right, although you hope it is much more than that. But there is a degree of catharsis in writing, and we writers are lucky in having that outlet. The effect is limited but it does help. I’m now old enough to have had numerous relatives, friends and acquaintances die, so poems about dying and what it means have become more frequent. When you’re older death is all around you.

You have written extensively on poets such as Keats, Yeats, and the modern Australian poet Kenneth Slessor. To what extent have these poets influenced you in your own life and creative practice?

It’s always hard to tell. I came to writing later than most poets. I disliked high school and it was only after I left that I remembered three poems with great pleasure: one of them was “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” And I do remember studying Slessor at some stage in school. I grew up in Sydney which is decidedly his territory; when I first went out to work it was at a chartered accountant’s office and I sometimes had to carry documents to different parts of the city. It was still recognizably the city he had known but which scarcely exists now: the city of wire cage lifts and old wooden panelled dark offices with musty smells. Yeats I read only when I met other would-be poets, and I studied him at university, eventually writing my PhD thesis on his work and ideas.

I learned from them all, sometimes without knowing it: from Keats the use of language for sensory evocation (which is his great gift to English poetry); from Slessor, the use of imagery to evoke ideas rather than state them; from Yeats, the extension of syntax to deepen the level of thought in a poem. All of them are very sensory poets who make a great use of images, although in Yeats it is more aural than visual. He had lousy eyesight.

All that concerns their influence on my creative practice; their influence on my life is beyond my ken! Keats is the only nice person out of the three. I would love to have met him. The other poet whom I realize has had a big influence on my writing is Philip Larkin, and he was a real creep!

Many of your poems are concerned with air travel, being in transit, and particularly travelling through Asia. What do these liminal spaces afford you in your capacity as a writer, and how has travel shaped your poetic mode?

When I was young I had immense curiosity about the world and was so keen to travel overseas that when I went, at the age of 22, it seemed magical. I went to Europe with a group of students and recent graduates organized by the National Union of Australian University Students; it was for three and a half months but I didn’t come back. I quit my job before going, I lost the airfare, and went to stay in Madrid for a couple of months to read and write, and just live in a foreign environment. I deeply wanted to get out of the small world I had grown up in and I wanted to challenge myself. I was away for almost two years, Rhonda and I got married in London, and we returned to Australia when she was pregnant with our first child, so my life and hers were completely different, and we had both grown a lot. We had an international outlook ever after.

My second career was as an academic and the most significant change to academic life during my career was its internationalization. I was a beneficiary of that, just as I was a beneficiary of being part of the first generation of Australians to whom overseas travel was fairly readily available. The COVID virus and environmental issues might make us the last too!

I had stopped in Singapore en route to London during that first trip and found it fascinating. Taking a job at the University of Western Australia in 1984, I was struck with how the immediate external reference points were not Papua New Guinea and New Zealand as on the east coast, but Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand. The proximity of Asia has led me to spend a lot of time in Asian countries, for research and conferences and in visiting teaching positions. For some reason I feel very comfortable there, even though I don’t speak any of the languages. I’ve loved the different ways of dress, food, manners, and of course I met many teachers and writers, a number of whom are still friends.

I have always found new environments stimulating, and that has prompted a lot of writing. I don’t know what it is about planes — perhaps it was that I had so little time and flights gave me attention with no distractions around me. I’ve examined a lot of theses on airplanes, too! I actually found myself writing a poem when I got on a plane so often that I stopped myself. I suppose that being in transit and being elsewhere just takes you out of your usual assumptions and habits.

Your latest collection, And Yet…., contains many ekphrastic poems in response to Rubens and Brueghel the Elder, Aguado, and Rembrandt, among others, and you have said that your creative experimentation began with painting. How do you find the relationship between poetry and visual art, and what does it mean for you to write ekphrastic poems?

I used to be sceptical about ekphrastic poems but in recent years I’ve become fascinated with them, especially poems about paintings. To work they need to be not “about” paintings but to use paintings as jumping off points. There’s no point describing what’s in the painting; the immediacy of line and colour will always trump the abstractness of words when it comes to description. What language can do that painting can’t is convey thinking.

Drawing and painting are the other art forms I love and know a fair bit about; I got through high school more through drawing than through writing, although I and a few friends did both. The two art forms have different relationships with time and space, and it’s the differences that make ekphrasis viable. I was determined to have the images printed with the poems in my latest book; earlier ekphrastic poems didn’t enjoy that.

Some of your poems make dry observations of capitalism, the economy and money. As a writer I often forget that in addition to things like visual art, these are also fertile subjects for poetic craft. What is your view of the place of poetry in an increasingly commercial world?

I see the arts, especially literature, as expressing our deepest feelings and knowledge of the world. The commercial world is important, and is not understood at all by most artists. My first degree was in business, with majors in accounting and economics, and my first career was as an accountant. That said, I hated it, especially its lack of creativity and frequent lack of ethics, and I worked very hard to get out of it. My poems about economics and money are all critical; it would be difficult to write poems in favour of money. That’s partly because we don’t need to — it’s already overvalued in our societies. Commerce is often based on shallowness — think of the tawdry psychology involved in marketing — and we have too much value given to shallow people and shallow activities in our societies. I think of the respect given to pop songs, celebrity “culture,” and President Frump.

There is a kind of genuineness to commerce in that if you lose money it’s likely that no-one will bail you out; you have to stand on your own two feet. However, it’s a world defined by competitiveness, like sport in our time, and competitiveness is an overly-valued human attribute in capitalist societies. Cooperativeness is much more important. A good poem is available to everyone who can read it; it doesn’t matter who wrote it. There’s no competitiveness there. The “Ode to a Nightingale” is wonderful to read now, no matter how many times you read it, and it will be wonderful for as long as humans exist. I see poetry, and the arts generally, as an antidote to the ethos of our era; it’s probably one reason why the arts are mostly ignored by those in power.

You have also written many beautiful love poems across your oeuvre, and your latest collection includes some for your partner, Annamaria. You have also judged statewide love poetry competitions in Western Australia. How do you write a love poem that avoids sentimentality, but has emotional endurance and force?

Love is the other great subject of poetry because it’s the other great subject of our lives. It’s not all you need, but you do need it, no matter how young or old, innocent or experienced, you are. I mean “love” broadly, not just romantic love. If you can write a love poem that works it will have force because that need and value is built into us.

However, we live in a tough age, and our aesthetics value — I think overvalue — originality. So it’s very hard to employ the traditional romantic images in contemporary poems, and it’s all too easy to write love poems that sound like verbal chocolate boxes. Songwriters can sometimes get away with it but not poets. I was very proud to end the latest book with a love poem that employs images of the moon!

A contemporary love poem requires absolutely authentic feeling — as do poems about grief — and a lot of technical skill. We seem drawn to conflicting feelings; thus, imagery that pulls both ways with a degree of tension at the core so that the positive feeling is hard won is often required. I think Yeats was the first to realize that. Many contemporary poets have written no love poems, or have treated love only with irony. I’ve always been drawn to what Yeats called “the fascination of what’s difficult,” and writing without easy irony is the great challenge for poetry ever since the Modernist revolution. It’s one of the reasons the reading public has turned away from poetry. I think that depth of thought and feeling are what matter in poetry, but you won’t find that said in contemporary literary criticism or theory; it sounds too traditional and not technical enough. You do need poetic technique to convey them, and you need more verbal nuance to convey positive experiences than negative. I find most contemporary aesthetics irrelevant to what matters in poetry; what matters is what’s always mattered. If you get down to it, it’s probably my love poems that I’m most proud of.