On Cork city’s Grand Parade there stands a derelict building, the front of which has been emblazoned with the words, “a city rising is a beautiful thing.” These words, which belong to poet Thomas McCarthy, are fashioned to the structure via a giant banner sponsored by Cork City Council. The poignancy, and perhaps irony, is that there are structures suited to such placards.

Originally from Cappoquin in County Waterford, McCarthy is arguably one of Cork’s most recognized literary figures, central to the cultural revival that took hold of the city throughout the 1980s. McCarthy belongs to one of the great generations of Irish writing, alongside fellow University College Cork alumni like Theo Dorgan and William Wall, who came up in the post-Montague era.

Having lived through the economic hardship of the eighties, much of the last decade might well have felt familiar to McCarthy. Art responds when cities both rise and fall, and so it is fitting that the words of this poet — who has witnessed decades of socio-cultural oscillation in Cork — should be used to mark the present ascendency.

But economic recovery is a problematic thing, particularly in a city where the opportunities of gentrification and globalization have never been realized. Cork is a fine place for those with attractive salaries placed in growth industries, but it is an entirely different place for those on the margins, watching the cost of living climb ever higher. At all costs, Cork must resist becoming Dublin.

Last year, Graham Allen and Billy Ramsell edited The Elysian (New Binary Press, 2017), a collection of poetry, short fiction, and essays which treats the impact of the economic collapse on Cork. Named for The Elysian, a towering homage of concrete and steel to the Celtic Tiger, the anthology features a poem by McCarthy, wherein he explores how this tower, then empty, was to bring the world’s wealthiest to “Shanghai on the Lee”.

Having had the good fortune to be involved in the publication of The Elysian, I enjoyed some correspondence with McCarthy throughout the manuscript’s proofing. I saw his literary voice reflected in one particular exchange, wherein he put his words to the task of interrogating the dominant political attitudes of southern Ireland, attitudes which can “destroy cities.” I do not wish to reveal in totality what was intended as a private message, but its eloquence was such that one cannot allow it to be effaced by the empty depths of an inbox.

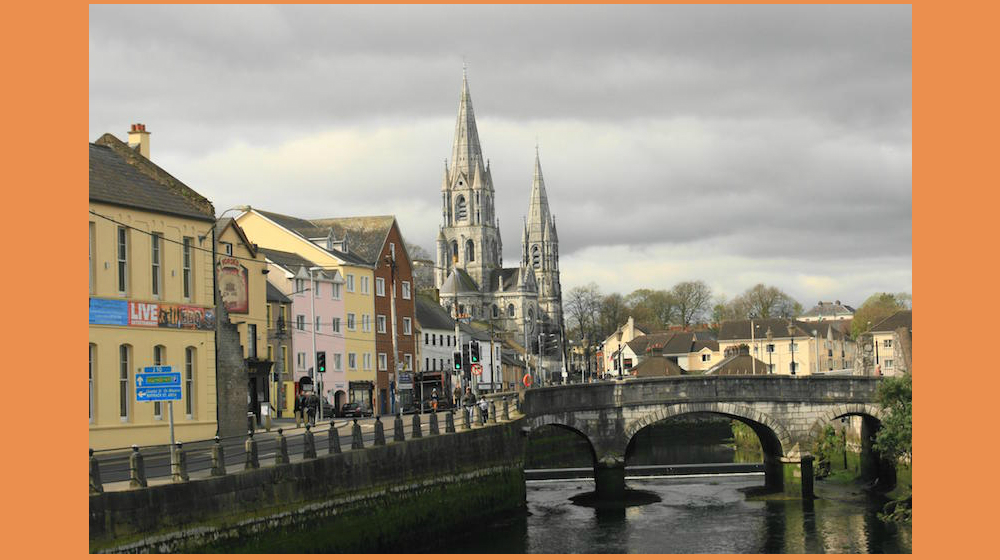

McCarthy began by tracing the origins of Cork’s urban decline, reasoning with the vicious neglect of the city’s “walls, gateways, inner urban built fabric, and suburbs.” He pointed to “local corruption” and “sectarian snarls.” Above all else, his image of Cork’s walls, our crumbling walls, our collapsing walls, the “rusted railings and arches” that line that path from MacCurtain Street to St. Luke’s, is what has remained with me these past few years. This neglect, he concluded, has given us a lesser city than we deserve.

McCarthy’s remarks led me to consider The Elysian as less of a literary collection, but rather, as an architectural contribution. However useful or futile a gesture, the collection has situated itself within the architectural heritage of Cork city. Many other works of literature have done the very same.

And now, as the city is rising, we see, perhaps more than ever before, the architects at work.

Not far from the Grand Parade, on North Main Street, yet another wall bears the words of a poet: “In my arms, you stir. A thousand streetlamps / flicker to light in the dusk. As I watch your eyes open, / the reek of roasting hops knits a blanket of scent around us.” The lines are from Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s “From Richmond Hill,” transcribed from Clasp, her critically-acclaimed collection of poetry published by Dedalus Press in 2015. Born in Galway and raised in Clare, Ní Ghríofa has called Cork home for the past two decades. The city is privileged to have her as an architect, to have its beauty recast time and again by words like the aforementioned.

The intricacy in Ní Ghríofa’s writing is that she can re-construct the experience of Cork in such simple terms: you can hear, smell, and taste the city as you pass through her lines. In a piece commissioned by UCC to mark Culture Night 2017, Ní Ghríofa asks for “a city of sound,” a city where “the air smells of smoke, and of stout.” For this reader, Ní Ghríofa’s Cork is the Cork, a city of smoke and stout where one could still smell roasting hops as they made their way up Barrack Street towards home, before cultural heritage made way for student accommodation. She concludes the poem with a simple request: “build us a city of hope.” In her words she has done just that, giving form to places that may no longer exist.

Ní Ghríofa’s schematics resonate with those of Cónal Creedon, whose introduction to “The Cure” presents one of the finest sensory maps of Cork ever to be penned. For Ní Ghríofa, Cork is all about sights, sounds, and smells; in Creedon’s “The Cure,” part of his Second City Trilogy, the city is all about the latter, it is a place where one need only follow their nose. Following his nose, Creedon’s protagonist brings us down to Patrick’s Bridge from his doorstep on Dublin Hill, guided by the scent of molten sugar, sherbet and toffee apples, by the bakeries and the slaughterhouses.

The smell of smoke and stout is here too, and while it is a “stale stench” that lingers from the night before, it is thought of fondly. The hallmarks of place are like that: we remember them as we want them remembered, thinking foul things otherwise because they are ours before they are anything else.

And perhaps our own false realities are true. Ní Ghríofa’s “Grand Parade” is a reminder that the places that make us are still there, however hidden by glossy paint. There will always be towers to cast shadows, but that one laneway, that one window, however dark, will persist, acting as personal relics. In signalling their own relics, Ní Ghríofa and Creedon use what remains of an older city to construct a Cork that is theirs, inviting us all to do the same.

Such relics are everywhere, both our own and those that have been signposted by other voices: one cannot walk Military Hill without seeing Graham Allen’s unborn Cork boy with matted hair, or pass a café and not think on Roisin Kelly’s beautiful people, alone at their candlelit tables, drinking coffee as the evening grows wet and dark. To know the literature of a city is to know that city, and to walk it with such knowledge is a harrowing and glorious thing.

The literature of Cork is literature of smoke and stout, of hills and rain. There is always rain, most notably in Danny Denton’s spectacular debut novel, The Earlie King & the Kid in Yellow (Granta, 2018). Denton’s post-apocalyptic Ireland has not seen the sun in centuries, there has only been rain. Reviewing the book for The Irish Times, Sarah Gilmartin notes that this is an Eliotic tale of unreal cities, of ruin and recovery. According to Gilmartin, Denton’s characters inhabit a “grim dystopian Ireland that is all too believable.”

It is possibly reductive to describe Denton’s The Earlie King & the Kid in Yellow as “a post Celtic Tiger novel,” because what is contemporary Irish writing if not post Celtic Tiger? But the truly grim reality is that we do not recognize how the brown fog is descending once more, and we are flowing over our bridges towards, to borrow from Allen, the “ghost factories,” unaware of the approaching rain to which we should now be so accustomed.

Denton’s novel is the epitome of the Cork condition, a dystopic and mythic reality full of social disparity and disharmony, full of rain. But there is hope, too, there is the belief that, even when all has been submerged, cities do rise again.

People are the redeeming force in Denton’s dystopia, or more precisely, the relationships between people, which are always borne of place. Denton’s fiction is another’s reality: the widely-celebrated Leanne O’Sullivan rooted much of her most recent poetry collection, A Quarter of an Hour (Bloodaxe, 2018), in reflections that emerged from her husband Andrew’s life-threatening illness. The collection describes how Andrew, his memory decimated by a three-week coma, began his recovery through illusory exchanges with animals.

O’Sullivan draws parallels between the visions of her husband and the potential for nature to scream back at us — both she and Denton are conscious of broader global issues relating to climate change, but both focus their treatment of this matter in more localised, and thus utilitarian, contexts.

It is fitting that O’Sullivan should offer her page to wilder things; she is originally from one of Cork’s wilder places — the Beara Peninsula. Where Denton’s heroic figure is the Kid in Yellow, O’Sullivan turns to local legend, the Cailleach, the bringer of rain, but also, the architect of great Irish places — the hills and mountains which will outlast any artificial structure.

Denton and O’Sullivan extract the most tender salvations from the direst of contexts: they speak less of our space than they do its inhabitants, their landscapes are all about people, and it is people who turn space as it has been constructed into space as it is.

Like any architect, the literary sort should be as concerned with form as they are with their linguistic structures, a trait perhaps best exemplified by Cork poet Billy Ramsell, whose second collection, The Architect’s Dream of Winter (Dedalus Press, 2013), shortlisted for The Irish Times Poetry Now Award, revives the poetic as melodic, the word as tempered, beaten into shape like the careful and chaotic geometry of a city.

Ramsell’s collection, recently translated into Italian by Lorenzo Mari (Libro L’Arcolaio, 2017), has lent this piece its central analogy, and indeed, its dominant message also has relevance: we will lose our humanity once more if we do not pay attention to the whispers and machines. Our urban spaces are being overrun by whispers and machines. The Cailleach may bring winter at any moment, but perhaps it is winter that we need.

Cork’s literary community is thriving, though it is much poorer for the loss of Matthew Sweeney in August. The Cork International Poetry Festival and Cork International Short Story Festival, both run by Pat Cotter and the Munster Literature Centre, continue to become two of the major literary festivals in Ireland, the UK, and possibly all of Europe. The emergence of wholly and semi Cork-based periodicals like Banshee, The Penny Dreadful, and The Well Review continue to provide platforms for new and established voices alike, while the re-emergence of Southword as a print publication will ensure that the fledgling titles do not have the city entirely to themselves. Community gatherings like Ó Bhéal continue to draw impressive numbers, and most importantly, people are writing, and hopefully reading.

As the city rises, so too will its literature, and it is through our authors that we will find the corpse paths we so desperately need. The voices that speak for any city soon become its architects, their words operating as histories, warnings, and inspiration: here is how a city should rise, they explain. Whether or not anyone is listening, in Cork we can at least be grateful that our architects are still dreaming.