Originally published on LARB Channel Avidly, Claire Jarvis recounts her experience of watching The Wire again.

It’s deep in July, and there’s nothing on television; the season of rewatching is upon us. My partner and I have decided on The Wire. The first two times I watched The Wire, I was living in the Baltimore it claimed to represent. I had moved to the city for graduate school and the twin towers had fallen on the first full week of classes. I watched the news coverage of that event on my 13” television (with combination VCR) and hoped to God my lone pre-a-week-ago friend would come over that evening so I wouldn’t be alone. Part of the power in The Wire comes from its representation of urban destruction to a wider world that had just come into consciousness that it, too, could possibly be destroyed. Baltimore, that gorgeous nineteenth century city, with row after row of working peoples’ houses, housing that had been filled in the booming forties and fifties, had been steadily shrinking for almost a half century when the towers fell.

Everyone talks about The Wire’s realism, which in literary terms means the show attended to the material details of everyday life, and exploited the vernacular and dialect to craft a convincing representation of “real” people – in The Wire’s case, this focused on representing poverty as much as it did on representing social power and corruption. Though the show clearly speaks to these realities, and draws from a long aesthetic tradition, its relationship to Realism (capital-R) remains vexed. Further, my perspective on The Wire’s Realism and the worlds it claims to represent is complicated by my lived relationship to Baltimore. The Wire tracks a different kind of urban destruction than the repeatedly rewound images of the towers falling did. It’s a slower tragedy, and, unlike the show, has not yet ended. Even if watching The Wire helps us understand a tragedy, it’s not in itself a political act. Watching it doesn’t fix Baltimore, any more than watching the towers fall helped us put them back together. And for me, rewatching it elicits a troubling sort of nostalgia for a place that I called home for seven years, but which I now realize I was never truly from.

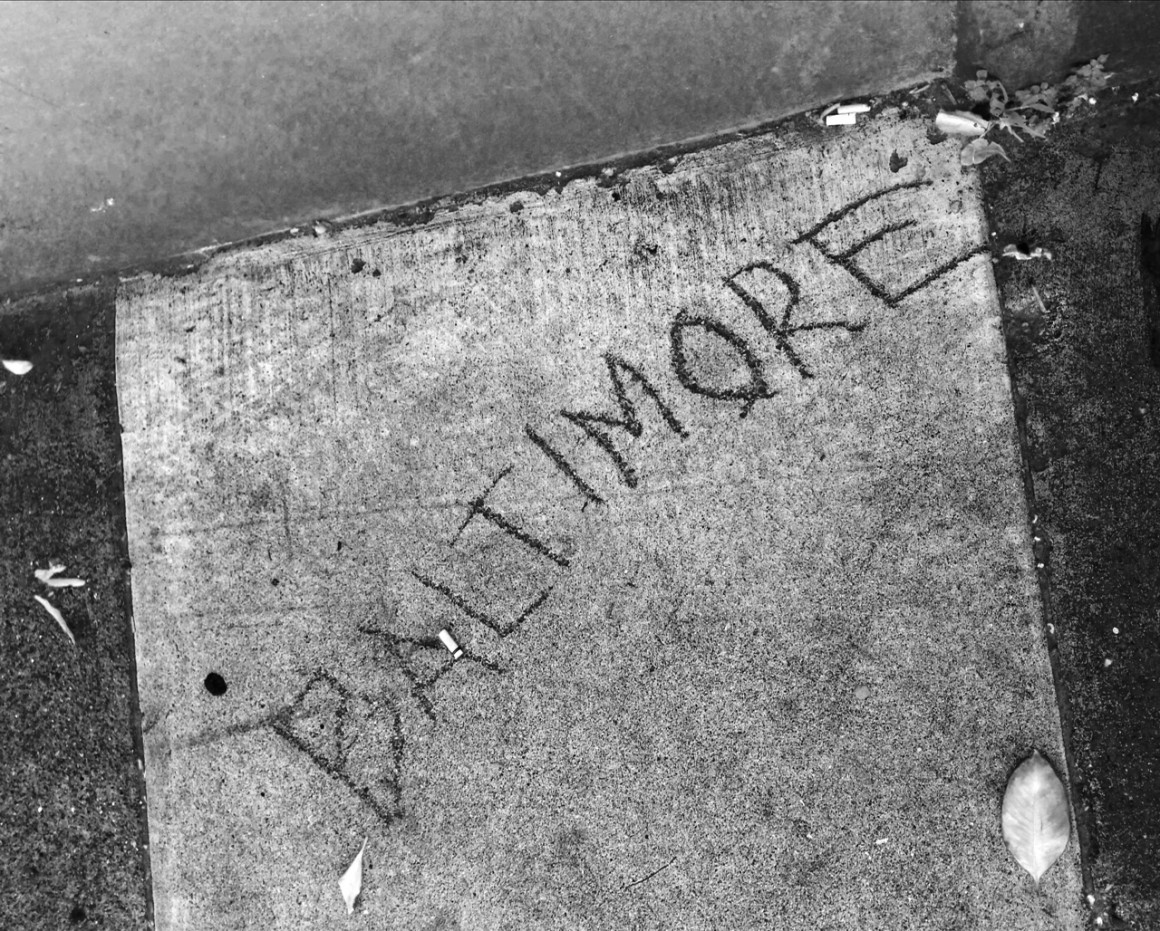

While I lived there, though, I was proud of being “from” Baltimore. I loved the city’s majestic nineteenth century body, and the loopy way that body had been broken and massaged into the 20th and then 21st centuries. Baltimore is a welcoming city, especially if you worked in a store like Video Americain, as I did, to flesh out my TA paycheck. I had access – to people, to art, to music, in a way that reminded me of my college years in Chapel Hill. But in Chapel Hill, I’d always felt like an interloper. I was only there temporarily. Baltimore was more grown-up than that. Or, I convinced myself I was more grown-up than that. The city felt like a place an artist could live. It was a place I could live. Even though my reason for being in that place was so very institutionally grounded, I could moonlight as a city dweller. I could pretend that this vibrant, curious city was mine, too. Charm City. The City that Reads.

Of course, I saw evidence of the city’s battles with violence and poverty everywhere. The bodegas of Baltimore do indeed have heavy, built-in lazy-susans with anti-shatter plastic that proprietors use to exchange cash for Cheetos or beer. My first year there, someone broke into my apartment and stole my Walkman and a tiny enameled jewel box my grandmother had given me. Once, someone stole potted plants off my porch. On warm summer nights, especially on July 4th, you could hear handguns being shot off into the night, in celebration, though it might also eventually turn to something else. But this is ethos, not environment. I never saw a gun. No one offered me drugs stronger than weed. As “real” as I felt The Wire to be as a Realist project, it was always a real that hovered just beyond my reach, just to the side of where I stood.

Watching The Wire again, I’m reminded of my first go-round, full of the seeming-insider’s excitement of recognizing that the club Marlo held court in was actually, really the basement of The Brewer’s Art. I was surely on the inside! I’d rented movies to Lester Freamon! But I wasn’t, and I never would be. I hadn’t noticed that Bubbles and Ziggy both said “caper,” a little narrative glue that stuck their two characters together in an unsettling brotherhood of hopeless hope. I’d seen the boarded up rowhouses as settings for gangland murder, not as places I might, in another life, be from. I’d been too preoccupied with noticing that the characters realistically said “wuddur” for water and “Balmer” for Baltimore. I’d noticed exactly the things that anyone, from anywhere, would notice about a show written about Baltimore. I had recognized Realism in its full-throated song. But, I’d missed all the details. I’d fooled myself into thinking that Realism was real.

In the same way, young people in cities across the U.S. fool themselves into thinking the overpriced, slightly ratty apartments they live in are an experience of “the real.” But so many of us—graduate students, editorial assistants, shop-girls and boys, artists-cum-baristas—can, and will, leave. My parents don’t have money, but they do have a spare room. This isn’t an unreal relationship to place. But it is the only relationship to the real that Realism offers: a deep, experiential description that always has a final chapter.

****

I wasn’t ready for how strange rewatching The Wire would be. The first time I watched it I was still working at the video store where Clarke Peters came in to rent a lot of avant-garde dance. My Video Americain co-worker scouted locations and came into work late, sweating and exhilarated from the better, realer work. Sonja Sohn ordered carrot juice in the café in the basement of the apartment building I moved into the next summer. Someone told us of a wild party a cast-member threw out by the Whole Foods (the old one), where floating condoms had been found in the pool the next morning. There was a robust scene in Baltimore in the early aughts, and at its center was the large-scale production of The Wire.

And it’s funny, in the intervening decade, how tightly bound The Wire and Baltimore have become. When I came out to California to interview for my job, the conversations, once they’d covered all the usual bases, turned to The Wire. Was Baltimore really like that? What was it like? I could roll out my few Wire-adjacent stories and feel like I’d given some sort of proof; I was from Baltimore, I was a local. But I had no idea. The Wire was never real. I gave proof that I lived on a television set. Or, next door to one. The problems The Wire sought to expose – drug-related violent crime, political corruption, horrifying inadequacies in education, housing and medical care – all of those problems are still there. And, even with the recognition that this Realism has been seen, uneasily stomached and processed – nothing seems to have changed. But, why did I expect that fictional exposure would help solve real problems that had been decades in the making? What late capitalism seems to want to make happen, everywhere, now industrialization is never, ever coming back. Maybe Realism can’t help? Maybe shining that light only kicks back a strange amalgam of pleasure and worry, vicarious belonging that doesn’t solve anything, because to solve the problems would be to dismantle the story. Or, maybe Realism can only come from people who can claim the experiences they describe for themselves; maybe the problem is that the story, told only from the side of the police or teachers, will always minimize the experiences of the people they long to save. I’m not sure.

In one of the lectures I TAed for in grad school, we guided our students through a reading of Mary Barton. One of the central aims of Elizabeth Gaskell’s book was to expose the shocking conditions of the Manchester poor. “Han they ever seen a child o’ their’n die for want o’ food?” asks John Barton, the novel’s avatar of reform, however weakly effective that reform might be. Mary Barton, I argued to my students, was Gaskell’s way of shining a light on the horrifying inadequacies that industrialization had brought. But, what light can we shine on industrialization’s aftermath? The houses are boarded up, there’s no work to be found, but still people have to wake up and live each day.

It’s hard to admit I’m still enjoying The Wire. It’s a fascinating narrative achievement, down to the little Dickensian incentives (Nemo!) that make watching the stories unfold such a pleasure to a professorial type like me. But, I’m finding it harder to sit through the violence and immiseration, especially now that I know what’s coming. The brief spurs of hopefulness that the writers gave us – Bubbles going clean, Jimmy settling down with Beadie, Poot surviving the series – all seem frozen in amber. What happened next? Which of them would be the first to slip back into old ways, old habits? Video Americain closed its last shop earlier this year, though it’d been hanging on through the streaming revolution better than most. A lot of the people I knew in Baltimore moved away. Mary and Elliot moved to Charlotte. Elke’s in Germany now. Who knows if Jeff’s still in New York, but Justin seems to be. I can tell from Facebook.

As we watch now, in San Francisco, I tell Vince little bits about the show. “Oh, that’s Formstone.” “They tore that down my first year.” “That was actually shot in Hampden – so funny.” He’s only ever driven through Baltimore, so I’m safe with him. I can convince him that I briefly knew the city, even if I never really did.