(With today’s post from Boom, the LARB Blog continues featuring content from its new Channels Project. The LARB Channels — which include the websites Avidly, Marginalia and Boom — are a community of independent online magazines specializing in literary criticism, politics, science, arts and culture, supported by the Los Angeles Review of Books.)

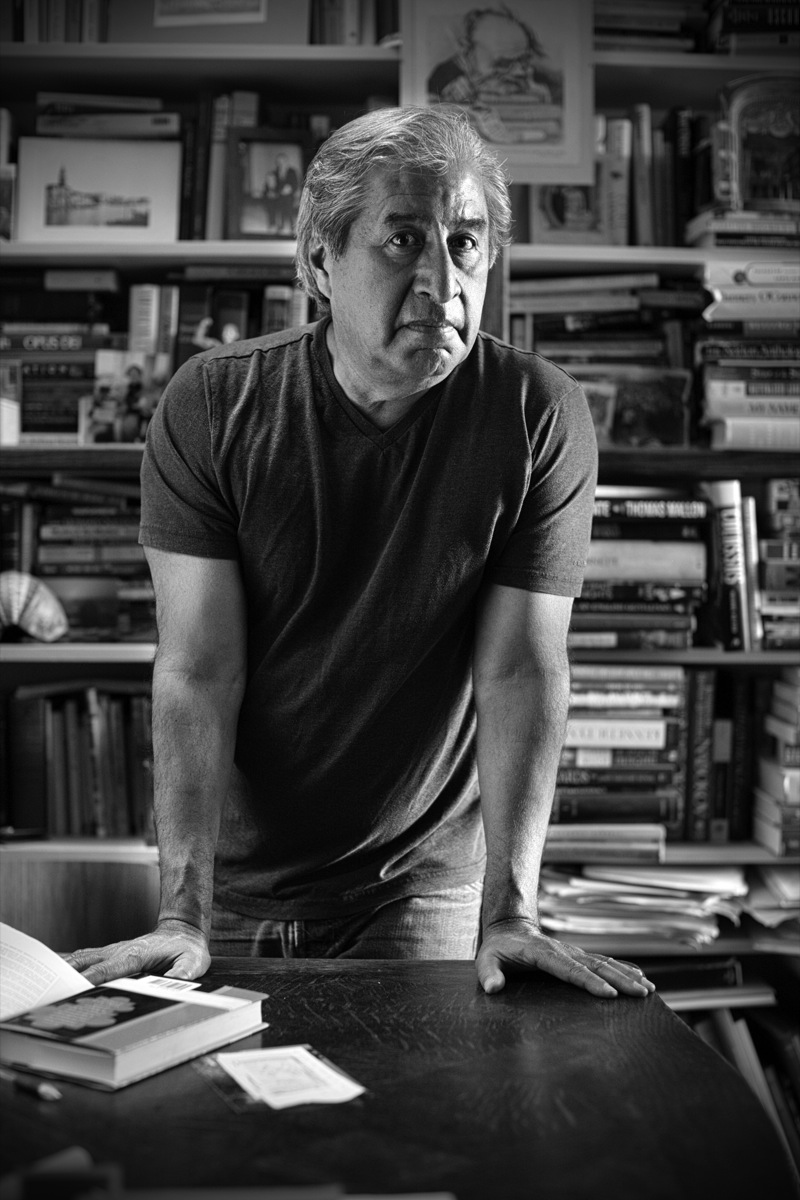

Recently, Boom interviewed Richard Rodriguez. They called the interview “California Soul,” and it’s certainly full of that: “It’s hard to read Richard Rodriguez’s essays and books without feeling that there is something deeply Californian about them. Every one of his books — Hunger of Memory: The Education of Richard Rodriguez, Days of Obligation: Arguments with My Mexican Father, Brown: The Last Discovery of America, and Darling: A Spiritual Autobiography — takes place, at least in part, in California. Rodriguez has lived in California nearly all of his life. So what is it that now makes him say he once was but is no longer a California writer? There is something world-weary in the statement. Rodriguez has seen too much of the world in California, and perhaps too much of California in the world. At his writing table in his apartment in San Francisco, Rodriguez spoke with Boom about California’s soul, why he is no longer a California writer, what’s the matter with his hometown, San Francisco, these days, and love.” The beginning of the interview, where Rodriguez muses about his time in Los Angeles as a younger man, is below.

From “The Boom Interview: Richard Rodriguez” Conducted by Jon Christensen

Boom: In your last book, Brown, and in your new book, Darling: A Spiritual Autobiography, you write about your friendship with the late Franz Schurmann and his book American Soul. Could one write about a California soul?

Rodriguez: I don’t know. That’s a really good question. I do think that I tended to read California as a Midwesterner. I had conflicting images of California. One was my uncle from India. The others were my parents from Mexico and the Irish nuns, to whom I dedicate Darling. They were almost all foreign people who had come to California.

But when I was a newspaper boy for the Sacramento Bee, everybody on that route or at least the majority, I would say, was from the Midwest. I would collect their subscription money—I think it was $2—every month. I would be at the door, and the lady would say, “Is it cold outside?” I said, “It’s freezing out here.” She said, “Oh, honey, that’s not freezing. If you want freezing, go to Iowa. This isn’t freezing. It’s a little chilly out here. Why don’t you wait in the hallway?” So I had an experience through her eyes.

So I guess I had a Midwestern soul as I was growing up, and a sense of relief for living here, but a sense of wonder, because I didn’t see snow until I was about twenty-two years old. I had never seen snow, except in the movies. The Central Valley of California got very hot, but it was also life giving—agriculture everywhere. You could smell the burning in the fields in the autumn, and at the State Fair at the end of summer, almost as a climax of summer before school started, there was a central pavilion, which of course was torn down, in which every county contributed agriculture. Tehama County. The agriculture products of Tehama—I don’t even know whether I’ve been to Tehama County even to this day—were beautifully displayed. It was so beautiful to see that California, that benevolent California, and even a place like Los Angeles was contributing lemons to the fair, you know. You didn’t see Lana Turner. You saw lemons. I knew that I was related to that place. And the Sacramento Bee used to have on Saturday a special section with agricultural news. It was called “Superior California,” and I did not understand what that was, whether it was superior in the sense that we were better than other Californians or what. I found out later from my brother it just meant Northern California.

Well, did I have a California soul in those years? I guess I did. When I came to Los Angeles, which I discovered after having been in London, I discovered a city that suited me. It suited me in the sense that I liked all of it. I found its architecture reminded me of Sacramento a great deal, and somebody would tell me, “Well, this little house, this little bungalow cost $2 million.” I would find it amusing. It’s like the bungalow I grew up in, except once you went inside, of course, they tarted it all up and so forth.

LA seemed to me both the combination of something I knew in Sacramento and then not. And the not was Mexico. It was filled with Mexico. Mexico was teeming around me. And the people, you know. Coming out of a breakfast in Santa Monica, this skinny kid would come up to me and start talking Spanish and say he just arrived. He would ask me for impossible directions. I had no idea how to get to Tarzana. I didn’t even know where Tarzana was, because my LA was so limited. And then in the middle of all this kind of blond, bleached, muscular, exercised, gaudy, glamorous Santa Monica, there was this kid who was desperate. I couldn’t manage it. I didn’t know how to relate to him.

And then LA became more and more a city that in my imagination became more Mexican and more a desert city. I felt the proximity of desert. By that, I mean metaphorically desert, a city of want.

Read the full interview over on Boom.