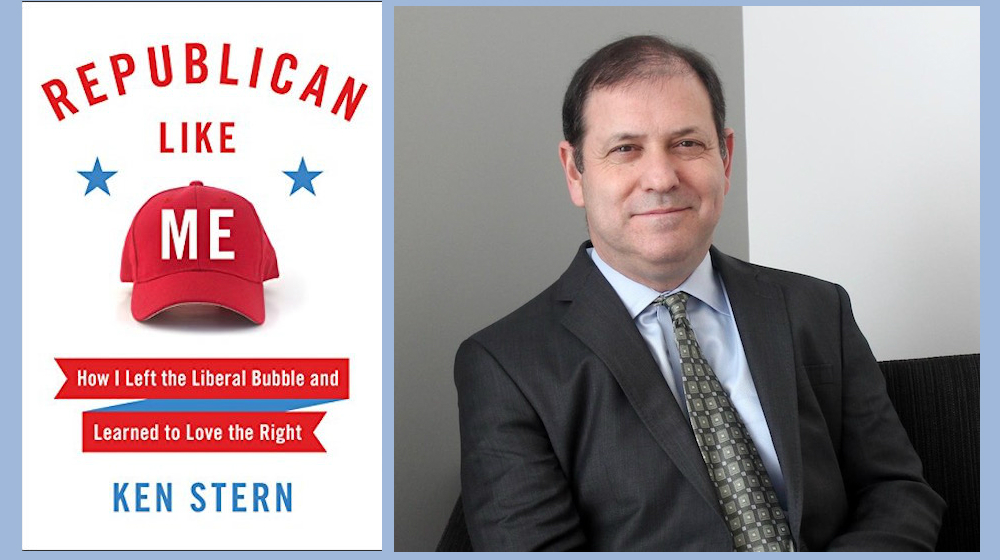

When should you travel across the country to hear out “the other side” en masse? When should you open your door to the few scattered conservatives on your liberal block (or vice versa)? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Ken Stern. This present conversation (transcribed by Phoebe Kaufman) focuses on Stern’s Republican Like Me: How I Left the Liberal Bubble and Learned to Love the Right. Stern is also the author of With Charity for All, a frequent contributor to Vanity Fair (where he writes on politics and media), and CEO of the communications firm Palisades Media Ventures. Prior to launching Palisades, Stern was the CEO of National Public Radio. Earlier in his career, he held positions in Democratic politics. He began his media career with Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty in Munich, and currently lives in Washington, DC

¤

ANDY FITCH: We could start with any number of telling stats from the broader social picture your introduction presents, in which what Bill Bishop has characterized as our demographic Big Sort has created ever more insular communities, persistently reinforcing their own cultural-confirmation biases — with, say, most Americans now living in electoral “landslide counties,” with at least half the population considering one major political party an active threat to the country’s well-being, with an anxious white majority (misperceiving its majoritarian status as long-since eclipsed) acting like a threatened minority, with tribal identities pushing us towards zero-sum thinking in which we put more emphasis on others losing then we do on all of us winning. But within that gloomy broader context, could you also introduce your orientational point that even with such demographic disparities, even amid these increasingly intense cultural / rhetorical / emotional divides, Americans’ views on most key issues haven’t changed much over the past few decades, and most Americans remain squarely in some sort of political middle? How might you most proactively define that middle ground, in terms of foundational values perhaps, rather than just as some muddled statistical average amid the push-and-pull of partisan extremes?

KEN STERN: That’s a great place to start. In that broader landscape you describe, the fact that surprised me most was that our views, on an individual level, haven’t much changed about the role of government in society and of America in the world. You do see more and more people at the edges, or at least you hear from them more, but we generally agree on the contours of society and of our government, and on our responsibilities to others. Still I juxtapose that broad consensus with the fact that we’ve become increasingly angry at the other side about their views, even if those views haven’t changed much over time and even if the policy disagreements are not nearly as strong as we think they are. We’re being more and more trained to be angry at the other side. We believe the other side violates the norms of American society and culture. That’s the result of a polarized media, of polarized parties, and of social media that encourages us to dislike this other side.

In terms of perceiving other sides, we probably should introduce this book’s broader project. And here it interests me that Republican Like Me doesn’t document you traveling to, for example, the statistically most moderate or most median districts in America, or to communities with the cleanest, most transparent, most civic public discussions. Instead it seems like you wish to conceive of an American “center” that can include more contradictory perspectives, that forces us to bring together more intense pluralities.

This book started with my realization that I was increasingly living in a liberal bubble. The people I knew, the person I was married to and others in my family, the people I worked with, and the media I consumed all tended to reinforce my view of the world and to confirm the rightness of my view. But I couldn’t help juxtaposing this reality with the notion of other people in their own separate bubbles, just as secure in their own correctness, and with us increasingly isolated from each other. Your first question mentioned extensive social-science research. The stat that jumped out to me came from a Washington Post poll in Virginia, taken during the last election, on the percentage of people who don’t have close family members or friends voting for the other side. It was crazy how many people fell into that circle (myself included).

I actually didn’t know anyone who was going to support Donald Trump. And even though I started Republican Like Me before Trump became a presidential candidate, the book came out of that dynamic of isolation. I wanted to step away from that, and consciously spend a year or more really engaging with the other side, consuming other media, traveling to parts of the country I wouldn’t ordinarily visit (whether that’s Pikeville, Kentucky, or Youngstown, Ohio), spending time in evangelical churches. I mostly just wanted to meet people and talk with them about their views. It was really easy, face-to-face, to find common ground. We wouldn’t agree on all the details, and often one or both of us had some details wrong. But it was easy to find points of consensus, and to understand why sometimes people had different perspectives than mine.

Yeah I appreciated throughout that Republican Like Me doesn’t document escaping “the liberal bubble” and rediscovering reality, but instead traveling from one bubble to another bubble. And I especially appreciated your attempts to probe how slippery “the facts” themselves remain, how we need to try out a variety of divergent, apparently mutually exclusive points of view if we want to move closer towards a comprehensive perspective on a pressing social topic. But here could we also place such skeptical self-questioning within an acute political context that only has sharpened since you started writing this book, a context in which our current president consistently exploits the cynical notion that it’s all a bunch of lies, that one set of statistics can just be substituted for a competing set, that everybody just believes what they want to believe anyway? Or here I picture the classic well-intentioned, supposedly nonpartisan newspaper article which ends up suggesting to readers that a scientific debate continues on climate change, rather than the reality that conservatives once again refused to acknowledge that no scientific debate exists on climate change. Amid such cacophonic scenes, could you further clarify how the viewpoint diversity you seek to encourage might channel an ambitious, inquisitive, ultimately constructive (rather than overwhelmed, adrift, immobilized) approach to thinking through crucial social questions?

Well one basic challenge comes from the fact that we’re all low-information voters, though we’re expected to have opinions on lots of different things. My personal challenge was that, even as a highly educated guy who lives in Washington, D.C., there was tons of stuff I assumed I knew and assumed I was right about, without actually having the experience, or research, or data to back up my beliefs. You see that, writ large, time and time again. People feel compelled to have opinions on things. They constantly have to ask themselves: “Who do I trust?” And mostly the answer is “Only members of my tribe,” or more specifically the signalers and leaders of my group. Most people can’t help thinking that way in this political environment. So I wanted to spend time with people who either don’t know who to trust or who have been trained to trust a different set of political intermediaries.

Even this past weekend, I went back to some people I’d spent a lot of time with while writing this book. One church pastor said things like: “I watch ABC, NBC, CBS, and then I turn to Fox, and I still don’t know who to believe.” So many of us feel very out at sea in this vast informational universe. It’s almost ironic. The more sources you have, the less you know who to trust and believe. You can read one seemingly straightforward news piece, and then find 12 others that say the exact opposite. And a lot of Americans do respond by just saying: “It’s all crap. I’ll just go with my friends, my common sense, the views that align with my cohort.” We say that over and over again. That’s a big part of America’s balkanization.

Here could we bring in your book’s title as well? Why “Republican” rather than “Conservative like me”? Does emphasizing “Republican” rather than “Conservative” already point more to a tribal, cultural, everyday-life identity, rather than to a philosophical, ideological, free-market approach — to more of a Donald Trump Republicanism than a Paul Ryan conservativism? And if we end up with only one question about your book’s title, then I find it hard not to bring in a preceding generation’s ethnographic-esque Black Like Me project, which your own book seems self-consciously to echo in some ways.

When I planned the book, conservatives and Republicans were in fact largely the same. How quickly things change! I started my research in 2015, when the idea of a Trumpist Republican party didn’t really exist. Throughout that year, I found myself talking to traditional conservatives in think tanks, as well as to conservatives in academia. But then a big part of the book came from me grappling with this whiplash between the conversations I had at the American Enterprise Institute or the Cato Institute, and the conversations I started having with white working-class voters in eastern Kentucky or rural Texas.

And you’re right about that nod in the title to John Howard Griffin’s book. I was taking on someone else’s identity, trying to see things from a different perspective than I would ordinarily have in my day-to-day working life, here in my 94% Democratic D.C. ward.

I brought up your title as well because this book’s tantalizing promotional material might make it sound as though you’ve undergone some ideological conversion. I don’t really see that playing out here. I see you thoughtfully changing a little, not flinging yourself from one pole to the opposite. I see you arguing, let’s say, that, both historically and within our contemporary world, market-driven economic growth has in fact lifted many more people out of poverty than government programs have — but that government nonetheless needs to address the substantial social disparities and resulting poverty in present-day America.

This book’s subtitle, to put a fine point on it, starts with: How I Left the Liberal Bubble. As you said, when I left that liberal bubble, I went into the conservative or Republican bubble. As I say throughout the book, there is not a real America and a fake America — there are increasingly two Americas (or many, many Americas). And then my book’s subtitle continues: and Learned to Love the Right. This does suggest (if you don’t read the book, like many people today who judge books by their covers) that I underwent some amazing conversion to Republicanism or Trumpism. That’s not the case. I’ve learned a ton, but the “love” in the subtitle was for the people I met, rather than for the Republican Party.

We live in a world in which many leaders see at least half of the other side as deplorables. It’s hard to love deplorables. So I wanted to highlight the experiences of people I met, the respect I developed for their perspectives, even when I didn’t agree with them — and God knows I heard plenty of things along the way with which I disagreed. But I learned to admire so many people I met who had different backgrounds. I learned how to understand where they were coming from, and to see points of agreement. I learned especially that if we are to survive as a country, we need to recognize better the value of loving our fellow Americans, whether you agree with them or not. That’s the essence of a successful democracy. That’s the perspective we’re losing right now, when thinking of the other side as alien, as different, as lesser (all of which applies of course to liberals as much as conservatives).

You already hinted at the broader phenomenon of cultural signaling, in which we take our cues largely from peer interactions and from the often implicit messaging of trusted leaders. I find quite funny the studies you describe in which citizens offer their impassioned responses to supposed controversial bills shaping current legislative sessions — bills in fact fabricated by social-science researchers, who might attach the additional falsehood that, say, Barack Obama supports or opposes such a bill, to see how that shapes resulting opinions. I find especially frightening studies that show white voters, when faced with prospects of increased diversity, turning more conservative (and not just on immigration or affirmative-action policy, but on seemingly unrelated topics, such as environmental policy). I appreciate your real-life contextualizing of a situation in which you, living in your progressive community, might actively look bad if you don’t present yourself supporting gay marriage, whereas another American, randomly born into different circumstances, might risk much higher and harsher social / interpersonal stakes if he / she openly expresses support for gay marriage. And here especially I find the immersive aspects of your book project useful in showing us, under this sign of cultural signaling, how hard it can be to unbundle one component of, say, a Republican or Democrat or conservative or progressive lifestyle orientation from all the other components. So could you describe what writing this book taught you specifically about that difficulty of just breaking away from those one or two most ridiculous elements of one’s political-cultural identity — without finding oneself truly isolated, truly adrift?

You see things like that all the time. Just yesterday I hosted a student from my alma mater, Haverford College. We talked about how difficult it was for him, as a center-left student, in the modern-day college atmosphere, with one loud group speaking very passionately about issues from the left. Who knows what the majority thinks? But on a personal level, it gets really hard to go against the norm, even in an environment where open debate is supposedly valued.

Then take that dynamic into a community where most people spend their time thinking about what’s going to affect their family today and tomorrow, talking about kids, or church, or football — and don’t spend their time on political debates of the day. Inevitably a small group, especially around identity issues, will drive the public conversation. It’s hard to resist, to speak against, or even just hold different views when it gets so tense. When you engage in a conversation by being told it’s your side against the other side, that your side is right, that the other side is wrong, it becomes increasingly hard to question, with whatever available amount of brain space, that there might just be some good ideas on the other side. And again, very few people in the country actually spend much time thinking about or talking about climate change. Of course they might in some circles. But I went to a lot of places where, when people talk politics, it’s mostly about jobs, education, or the economy.

Here we perhaps should draw on your own personal experience going public with some moderately heretical political claims. For example, if we take your writing on calls for gun control, I first should present myself as sometimes skeptical of Republican Like Me’s position (uncertain if / when you might cherrypick with your statistical evidence), but definitely too uninformed to challenge you on legitimate argumentative grounds. So instead I’ll do my best to present fairly your book’s broader claims that the particular types of gun control most liberals would call for (say a renewed assault-weapons ban) historically have not proven themselves to reduce rates of gun-related crime, and that impassioned public conversations about such policies distract us from discussing how to minimize social factors that do appear to correlate most directly with violent crime (such as economic despair, a lack of job opportunities). Of course you also do question certain rhetorical tendencies from pro-gun communities, for instance an insistence on constantly needing a gun to “protect” oneself, but with quite few gunowners you meet ever actually needing to have carried their gun into some real-life dangerous situation. But so could you correct (however you see fit) my depiction of your general take, and then describe how your own peers and broader community have responded to that take?

Here I probably should recast in some ways my earlier description of the book. One of my first, most basic ideas for Republican Like Me was: let me take on a few issues. Let me frame this book around a few issues I’m sure I’m right on, but that I (like most people) have never really delved into.

Guns were issue number one. I was sure I had to be right on that. I was sure the other side had to be wrong because it was just obvious. So the book has a long chapter where, on a personal level (going pig-hunting and attending gun shows), I dive into personal narratives around guns — but I also immerse myself within a difficult set of social and behavioral theories. From both of those perspectives, I began to appreciate that there’s a lot more complexity on this topic than I would have liked to believe.

I’m all for gun control, because I don’t see much downside to it. But now I just don’t have much faith that gun control will actually move the needle. We’ve learned over the last decade, from actual experience, that gun violence definitely can go way down in this country without much new gun control. So why aren’t we spending the time applying those lessons, and investing in things that actually might drive down gun violence even more?

In terms of how my neighbors and peers respond to all this, it’s a very interesting dynamic. On social media and places where people can feel safely distant from their target, people can get very angry about what I’ve purportedly done (though very few if any of those angry people have actually read the book), very nasty and mean-spirited. But when we have a chance to sit down and discuss the complexities and the actual data, then most people are wonderfully thoughtful about that. When I’ve had the chance to sit down with my neighbors (who my book uses a little as a totem for liberal bubbles, maybe a bit unfairly), and to actually talk about these things, those conversations are incredibly rich. Again, it’s the detached perspectives on social media or on television or in the President’s tweets that tend to pull us apart.

And do you find the same ability to engage diversely on these issues in the Republican bubble? Does “viewpoint diversity” itself suggest an inherently liberal (in the classical sense, but also here in the contemporary American sense) project? Or what models could you offer of conservatives themselves supporting the spread of viewpoint diversity?

I’ve never found that behavioral patterns change much from side to side, in terms of willingness to engage. And I’ve never considered it my mission to go out and try to persuade people on the right that the left is correct. This book operates more in the listening mode than the persuasion mode. But it’s not like I’d sit silent for days on end, without sharing certain views or sharing data. And I found a lot of people surprisingly nuanced in their views. We often lose that side of this broader story. People do want to gravitate towards a unitary, shared sense of truth. And I wouldn’t call these people I met the “silent majority,” but maybe “the silenced majority.” They want to find points of agreement, but often just don’t see that offered on our rigid political stratum. They might want to gravitate towards “the middle,” but they are consistently told that that’s not the place you should be. One irony of our current polarized environment is that more and more people self-identify as independents, mostly because they are embarrassed to be associated with one of the political parties.

Conversely, in terms of supposedly constrictive communities, I found your account of evangelical communities fascinating. You present such communities (plural, of course) as much more complex, diverse, ever-changing than many of us have been taught to believe. You reference young evangelical groups (themselves still tied to quite conservative institutions) most enthusiastically attuned to conversations around Black Lives Matter activism, efforts to mitigate economic inequality, addressing the needs of refugees. You track the increasingly substantial presence of student dissent and of pro-gay initiatives at, say, Jerry Falwell’s Liberty University. You hear even from established leaders of familiar (some might say all-too-familiar) conservative Christian enterprises like Focus on the Family about the need for evangelicals to pivot away from telling others how to act, and towards showing society God’s grace through the active doing of good works. Could you outline a few key social issues on which liberals would be foolish not to seek out consensus with a broad range of evangelical communities? And can we still maintain a healthy skepticism here and differentiate substantial policy changes from more superficial changes of tone in such communities? I appreciate hearing, for instance, of the tens of thousands of Christian volunteers helping a defunded Oregon state government fulfill its public mission — but I also sense a potential rationale for defunding the state all the further.

I started off this journey as an agnostic Jew from Washington D.C., who had never been to an evangelical church, even though that’s now the largest faith in this country. I realized, over the course of this journey, that much of my understanding of the evangelical community came from people like Jerry Falwell Sr., dead for over a decade now, still salient to parts of this community but far less influential and relevant than in his own lifetime. And when you start talking about tens of millions of people, you do find, of course, an interesting spectrum of ideas and changes. Today’s evangelical community looks quite different than the evangelical community of 20 years ago, and 20 years from now it probably will be that much more different.

How this community will change depends in part on how the rest of the country engages with it. When you can put the demagoguery aside, you find people a lot like yourself. I talked with people (as you mentioned) in Portland, where Sam Adams (the first openly gay mayor of a major U.S. city) had forged a big partnership with the local evangelical community — because he needed help, and the evangelical community wanted (as they might put it) to be known by what they were for and not by what they were against. This mayor and this community found much common ground. Many goals of evangelicals and secular liberals actually overlap. Think about solving the challenges of poverty — particularly the economic conundrums faced by any single-parent family. That tops the list for a lot of evangelicals, as does housing the homeless. And evangelicals might hold different views on the roles of church and government, but their views are often not radically different from more liberal communities. Very few people disagree that government needs to play a role, and that private charitable organizations also need to play a role. These are questions of degrees. When you can shift from “We’re on different planets” to questions of degree, when you can set aside the business of trying to demagogue the other side, it’s often not that hard to find common ground, even if you’re still going to disagree on some aspects of the conversation.

Those of us representing a liberal secular position might often present our case in unnecessarily dismissive, judgmental, harsh, exclusionary terms, in relation to a broad range of Americans’ religious beliefs (including many voters that liberals often take for granted as inevitable components of the Democratic base). But to what extent have such overzealous liberal / secular critiques in fact helped to bring about these more recent trends towards evangelical tolerance, inclusivity, and proactive citizenship that your book celebrates? Would you argue, say, that evangelicals would have started to separate themselves from at times truly hateful rhetoric and practices at an equivalent pace, without any such prompting along the way? Or what constructive (if imperfect, unnecessarily abrasive and alienating) social dynamic could we flesh out here? And I don’t just mean: what have liberals taught religious conservatives? I mean: what might liberals likewise learn from seeing certain evangelical groups hear out, absorb, and proactively reposition themselves in response to at times searing, overly personal, overly hostile, and un-reflectively prejudiced critiques?

There is that top-line critique of a certain generation of leaders, like Falwell and others. That’s a fair if somewhat un-nuanced description. You still find many people…let’s call them uncomfortable with modernity, with that discomfort reflected in some awful behavior. And even though I do see clear changes, these changes take place over years, in a very large population. So when are the right times to push back and demand change? When should you engage and try to support the best of what you see? There are lots of different strategies. Obviously the social change around gay marriage occurred (in the grand scheme of things) blindingly fast, though I’m sure it didn’t feel that way to people who had wanted to get married for decades. But it didn’t happen without individual evangelicals being changed. They had learned from their past poor behavior. I talked to some of the current Focus on the Family leadership. They told me that their prior leadership didn’t reflect their values of service and dedication to the public good, and that’s what they now want to be known for, not their political views. Liberals still miss a lot of this complexity when they look at these huge groups of people and try to find easy answers.

Here we could take as one concrete case-study you describing your own surprise that late-20th-century evangelical concerns about “the decay of the American family” (of course with any number of fraught sexualized, racialized, patriarchal presuppositions attached) have proven at least partially correct in diagnosing a distinctly American problem, in which high rates of single-parenting limit lived outcomes for countless individuals, broader communities, society as a whole.

I’ll put out a little bit of religious historiography. When I first approached this religious perspective, packaged as an insistence on the nuclear family, with one man, one woman, 2.2 kids (or more) as the right family, I took this as a religious precept divined from God’s will, rather than as a doctrine based upon economics or social policy. And for me, when people start lecturing me on God’s will, I find it hard to avoid a certain amount of innate skepticism, perhaps even some eye-rolling. But as I went to evangelical churches, and preachers discussed parts of the Bible where Jesus talks about divorce, I heard an emphasis on the underlying social ills of divorce in Jesus’s time, how women and kids were left penniless and without support. So for Jesus or the Bible’s authors, marriage had an important social value — not because of some canonical decree, but because it helped keep women and children from lives of poverty. And that made sense to me, not as religious doctrine, but as social policy which still has some practical currency today.

Perhaps the strongest driver for how modern American economics play out at the domestic level is single-parent (mostly mothers) families. That’s a poverty trap. If we could find ways to solve this challenge of single-parent families, we would make a much larger in-road against poverty in this country, more than any single social program that has ever existed. So I hadn’t fully understood that, from a religious perspective, you might start from spiritual value systems in order to make points about modern economics. But if you have more context for some of these conversations, you see less bigotry or nastiness, and more of a useful model for how people should think about bigger social issues.

That’s a great example of you unbundling one specific idea from a much broader worldview, and giving us the most useful policy aspects of it. Or in case we haven’t yet done this clearly enough, could you also point to a couple social issues on which you see liberals best poised to make relatively modest policy concessions that might help to promote broader coalition-building? I think, for instance, of you outlining the potential reinvigoration of a “Rooseveltian” paradigm in which able-bodied working-age Americans who receive social assistance will face work requirements, but with such work requirements implemented smartly, with true occupational training ensuring that “the dignity of work” doesn’t remain some rhetorical chimera, with transparent metrics (and not some mean-spirited animus) helping us measure if / when these work requirements accomplish their intended purpose, or when they need recalibration.

One interesting thing I took from the work-requirements discussion (and this is also relevant to the last thing I said) is how often, on both sides, practical policy notions end up getting bundled with higher-order beliefs. Part of the whole idea behind the Great Society, as Johnson expressed it, was to turn tax eaters into tax payers. He thought poverty policy should find ways to try and get people on their feet so they can work. He and his contemporaries believed in the dignity of work, both for individuals and as a good financial plan for the country. Then over time, the original purposes for a lot of those Great Society programs got lost. Often, we gradually build a public narrative and set of values that would have been very surprising to the original creators of those programs. You see this happen over and over on both sides, where a timely political intervention becomes a permanent matter of right and wrong. Plunging into the history of that particular moment helped me to see a different story than I would have assumed.

Still on this topic of work, you offer many insightful points on a broader “free fall” facing communities populated by white working-class Americans without college degrees. You provide a compelling account of economic hardships faced even by those with jobs in these communities, with automation not only reducing overall hiring, but leaving less room for promotion in many industries, and with long-term union-busting making it less likely that many workers will receive a living wage — if “living” here includes aging, and taking on increasing economic responsibilities that require consistent salary raises. Amid your efforts to parse legitimate white economic anxiety from what liberals might reductively read as racial animus, you make the eloquent case that, whereas various communities (certainly various communities of color) have faced more severe, more demoralizing, more overtly (and at times insidiously) discriminatory economic conditions for much longer, working-class white Americans can’t help but bring their own sense of self-measure to these calculations — comparing their present fate to the outcomes of preceding generations, or to their own expectations, and sensing a nation in fundamental decline. We could pick up any of those leads, but for an overall question: had you not put in the research hours living out this book project, what would you not have realized, not have understood, about Republican Like Me’s broader claim that, at present, no American political party represents the interests of the white working class? And why should everybody, regardless of race or political affiliation, find this fact as troubling as you do?

A lot of us have been educated in the past few years about the declining status of the white working class: the decline in incomes, the decline in life expectancy, the rise in opioid addiction, the rise in single-parent households. These communities face the worst despair epidemic in modern epidemiological history. We’ve become conditioned to these facts. But most of us don’t spend enough time thinking about what this looks like from inside the white working class. From our liberal bubble, we might be tempted to say: “You know what? That’s just the way the world works.” A lot of people on both sides of the aisle have said this: “Automation is coming. It’s a hard fact, so get your engineering degree.”

We fail to recognize that a community in freefall has so much cultural dissonance to deal with. You get anger directed towards the people apparently in control of these broader changes. You get the sense that everybody else has abandoned your community. If you turn the clock back 25 years, the white working class was the bedrock of the Democratic party. If you turn it back 40 years, we used to write odes to the working class and the things they built. And now returning to the present, these same people (or at least their heirs) are viewed as deplorables. And we’re not talking about a few people but many tens of millions of people — at a time when the white working class still makes up 40% of this country.

You can’t have it both ways. You can’t have a cohesive country if you consider 40% of the population a bunch of deplorables. So I really wanted to understand, from within this group’s own worldview, why Trump appeals so much and to so many of them. That’s critical to understanding America’s future. Even if they dwindle down to 30%, that still will be a big chunk of our fellow Americans. We better be concerned about them if we want to have a successful country.

Well this book does track your travel through gun country, coal country, Trump country. We don’t see you encountering many liberals along the way. But in terms of broader social cohesion, did your travels offer any insight into how our media and electoral conventions of a red-state / blue-state split, and of winner-take-all politics, so often serve to disenfranchise huge portions of the population — those departing from the majority’s norms in these supposedly monolithic communities? Or we could reverse this question and focus on those hypothesized Republicans you find it so hard to track down in your own neighborhood. When might you find it most constructive for big-city liberals not to fly to Wyoming and question the heartland people, but instead actively to seek out the conservatives down the block, who might feel marginalized, might appreciate the gesture, might prove quite useful as intermediaries between the liberal urban communities they live in and the rural conservative communities they vote with?

Again we could talk about evangelicals (or I should always say: “white evangelicals,” just one particular subset of the evangelical community — which has so many black evangelicals and Latino evangelicals and Asian American evangelicals). When we mention the 80% of evangelicals who voted for Trump, that might sound as monolithic as any community out there right now. But the other 20% are still millions and millions of people. Some live in liberal New York City neighborhoods. Some live in Trump country, or coal country. Some would have voted for Bernie Sanders if they’d had the choice.

And more broadly, even in landslide counties, plenty of people have alternate views. That’s always been true. The challenge has been to find effective ways to integrate these increasingly marginalized voices. Even in my 94% Democratic community, we have conservatives. They might be hard to find. You never see a Republican yard sign in my neighborhood. The 6% feels it’s probably not a good idea to speak out so publicly for the other side. And we should care about that. We all should celebrate and encourage viewpoint pluralism everywhere. That should be a core value for all sides, including the Democratic left — recognizing that having pluralistic perspectives (regardless of which of them you agree with) is a part of the democratic process, and welcoming your neighbors and their perspectives.

I asked about urban conservatives potentially serving as intermediaries. I have a related question about your own goal here, to undertake (to quote Lincoln) a remedial course in the “bonds of affection,” pushing yourself, again as your book jacket says, to practice self-restraint as you engage alternate worldviews, to steer clear of moralizing biases, and to seek out the best policy suggestions from all sides. I have to assume that certain audiences, especially liberal audiences, have pointed to your own social status (as a white, straight, professionally classed male) as providing you with the material resources to leave your bubble in the first place, and as protecting you from palpable threats that many individuals might immediately face if they tried to do the same.

Sure, when I speak publicly about the welcoming response I received in various places, with people willing to talk, to share, and to listen, someone in the audience will often say: “Great. That’s the reception for a white, prosperous, middle-aged man.” With the exception of being Jewish, I check most of the boxes that would fit into these communities. So how would I have been received if I were a black woman? Ultimately, of course, I can’t answer that question. It’s a perfectly reasonable question, and one I’ve puzzled over. But while lacking the tools to answer that question fully, I still would say that most people I met along the way went out of their way to characterize themselves as broad-minded. Sure, I have been trolled by neo-Nazis and have met some people saying truly crazy things. Those people are out there. But they take up more public space than their numbers deserve. The majority of people I talked to seemed to have a genuine interest in hearing different ideas and different perspectives, and deeply resented being pigeon-holed as close-minded and bigoted. I don’t think those facts come across enough in the typical public discourse.

But ultimately I can only tell my story, and hope my story means something to others, inspires others, gets people of all different types to say that maybe we need a different conversation. Maybe our view of the other side is a bit of a caricature. Maybe we ourselves need to get back in touch with a wider range of perspectives. And I’d I like to think that other liberals, whether they look like me or not, would at least have had some of the experiences I had — if they were open to that possibility.

Well let’s assume, if this sounds reasonable, that it’s true: some people only talked to you because you’re a straight white guy, and your social privilege serves as one foundational aspect of this project, and probably at times you can’t help unwittingly reinforcing that privilege. With all that said, why was it still worthwhile, both on a personal level and on a broader social level, for you to undertake this project? For example, maybe social status does here insulate you in ways you never could shake. But does it also offer you room to (like that imagined Republican in some progressive urban center) perhaps serve as a constructive conduit on any number of divisive conversations? And do you prefer (sometimes at least) picking up that role as social conduit over dwelling further on your own privileged status?

Again I’ll be the first to admit that I do have that privileged status. But like you said, hopefully this allows me to do something that opens up some dialogue. And it’s funny, when you go to places like Pikeville, Kentucky, this notion of “privilege” is a fraught one. No one there feels privileged about anything. They feel under siege and abandoned. The words they use are words that you often hear from minority communities. They perceive themselves quite differently from how others perceive them. That’s maybe what I found most interesting.

And given these perceptual dynamics, which Republican Like Me describes so well, I again never could tell whether your book had skillfully played to my own liberal tendencies to seek out empathy for “the other,” or whether non-liberal audiences would have felt the same. How have the people you wrote about responded to this book so far?

One driving resentment of a lot of people I met, in all these communities, was the feeling that they are demonized by the media, by the establishment, by the educated, by coastal elites. I encountered this overwhelming sense that they have been unfairly, inaccurately portrayed. And the overwhelming response I received for initiating these conversations wasn’t exactly gratitude (that’s too strong), but a favorable response that someone took the time to listen, to try to understand, and to portray these communities as they see themselves. That process itself requires continuous, ongoing respect and sharing and understanding between two different worlds which don’t interact very much — and where one side believes the other controls most means of communication, and doesn’t represent their community fairly.

So today, if there were a burning issue on which I felt the need to persuade the people or communities I met along the way, I could go talk to them. Three years ago, if I had shown up and presumed to lecture them on something, I wouldn’t have had credibility — because I hadn’t done the listening myself.

And again my role isn’t really to persuade anyway. I’m a chronicler. The fact that I could listen and eventually explore difficult topics with these communities showed my respect. That was probably the most meaningful part for me and hopefully for many people I talked to.

Finally then, given your past professional life, we of course could have addressed questions about supposed media bias much more substantially. Republican Like Me suggests that, while you used to think conservatives overreacted when claiming liberal media bias (given how much most reporters go out of their way, often to a fault, to present an even-handed account), you now recognize better how a homogeneity of viewpoints cannot help, however indirectly, shaping storylines. I’d love to have that bias fleshed out with a couple quick examples. Or for a broader frame of reference, here from own professional position in academia, I would assume you have had to think through before questions along the lines of: “OK, we do in fact comprise a concentrated liberal enclave, but in such a strongly capitalist society like our own, does it really cause such huge problems for a few sectors to pursue their inherently critical function through a liberal / progressive / left-leaning lens? Does a little occasional bias in the other direction really hurt anybody?”

First a lot of conservatives are completely off the deep end when they talk about constant liberal media bias — starting with the president, and then multiplying him by a thousand. That particular criticism has become a political tool unhinged from basic facts.

But sadly these distorted claims do have some basis in a reality which the media has never fully acknowledged. The challenge today particularly comes when certain high-quality news organizations like the New York Times attract a certain type of person, from a certain geography, with certain political perspectives. As hard as you try to stay balanced, that type of homogeneity affects what you consider important, which issues you cover, which voices you bring in, which triage of stories makes up the day. Often the concerns and perspectives of various communities never get presented. We would never cover race issues in this country only with white journalists, but the media feels way too comfortable covering political issues with largely liberal newsrooms.

That’s a serious challenge, without an easy fix. So when someone asks: “What’s the problem with that?” Or “Does it mean those liberals aren’t actually right?” I would say: maybe they are right. These are smart people, doing their damndest to provide high-quality reporting which we desperately need. But this homogeneity leaves the door open to the Foxes and the Breitbarts and others who exploit that dynamic — who see tens of millions of Americans looking at the media and saying: “They’re not for me,” and who have created this entirely different media universe that has spoiled the country. This doesn’t mean that the New York Times and Breitbart offer left / right equivalencies. That’s a crazy thought. But this bias has been part of the splitting which has opened the door to these other groups who come in and say: “Wait a minute. Those guys aren’t for you. We are.”