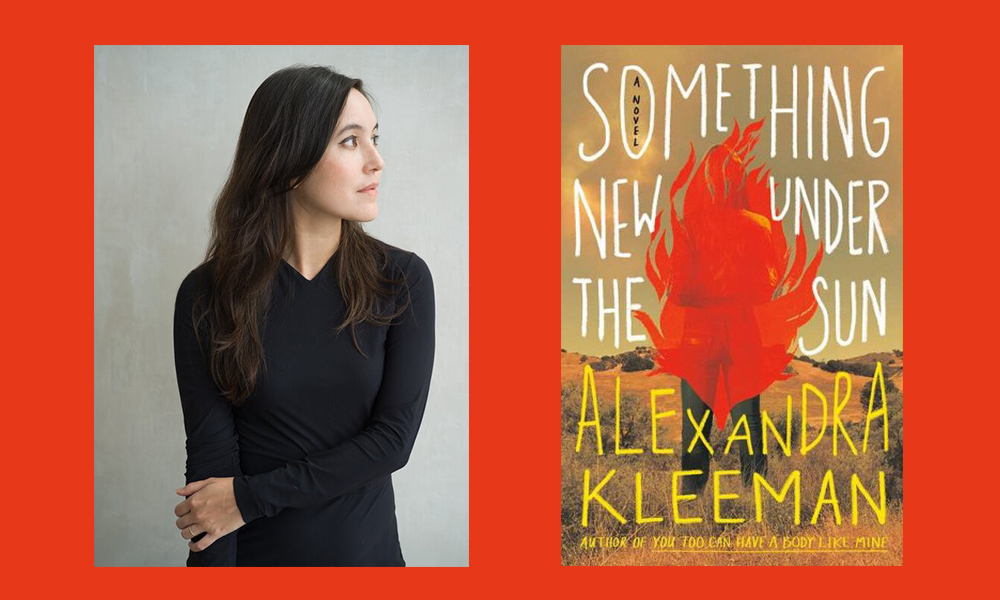

“When we rediscover that water is finite, it’s like waking from a dream and finding ourselves in a strange and rigid new place,” Alexandra Kleeman writes. It is in precisely this all-too-possible dystopia that her latest novel, Something New Under the Sun, takes place. Set in a drought-ridden Los Angeles in which climate change has forced water to be replaced by WAT-R, a synthesized liquid supposedly equivalent to its namesake, middling novelist Patrick Hamlin is assigned to work as a production assistant for former child actress Kassi Keene. As the city is quietly ravaged by wildfires and hordes of lost dementia patients, Patrick teams up with Kassi to scour the Los Angeles landscape for the secrets to her latest film’s financing, and to WAT-R itself.

Something New is especially striking because Kleeman not only renders the threat of climate change with startling sensitivity and acuity, but forgoes centering the novel around anthropocentric melodrama in favor of a holistic view of the Los Angeles landscape. In doing so, she constructs a dystopia of today rather than an apocalypse of tomorrow. As Kleeman touches on a variety of topics below — everything from landscape architecture to optical illusions — she asks us to consider how to inhabit this dystopia as citizens: to understand our crumbling world, and to reconceive community building within it.

¤

DASHIEL CARRERA: In an interview with The Creative Independent, you mentioned your ideas for writing come through a slow daily process of absorption and accumulation that, in the dead of night, culminates in paragraphs. What were you absorbing as you worked on Something New Under the Sun? How did it come into form?

ALEXANDRA KLEEMAN: In terms of what I was reading, the book probably originated in the friction I felt teaching a course on post-apocalyptic novels. I had made a varied reading list — Octavia Butler, Yoko Tawada, Antoine Volodine, Claire Vaye Watkins, even a collection of fiction and nonfiction about the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, edited by Kenzaburo Oe. These books are gems: there’s so much creativity in each and a lot of differentiation in terms of affect, world-building, and how the post-world is imagined. But the emphasis on “post-” felt cumulatively crushing to me, and there was a certain machismo in, for example, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, that felt actively hostile to the practice of dwelling in our present, pre-apocalyptic moment and thinking about the culture and causality of disaster, how we might inhabit a moment where catastrophe has a presence but not an indelible one, a moment where we still have agency and investment in the world as we know it and its constitutive systems. Early in my research process, I also did a lot of reading on the history of plastics — the title of the book comes from an advertising slogan for cellophane, the first consumer plastic and an intermediary between the natural materials that had been used before and the subsequent deluge of omnipresent synthetic consumer plastic goods. Thinking through the history and context of this material was helpful in creating my own “new” substance, one that, like plastic, was initially sold to the public as an improved substitute for other materials rather than a unique substance with properties and risks all its own.

I was particularly struck by how emotionally evocative the novel’s attention to the threat of climate change is despite the oblique manner in which it’s addressed. The novel is littered with wildfires, drought, and disease, and yet these plights rarely make it to the forefront. I’m wondering how this might reflect the “moment where catastrophe has a presence but not an indelible one” that you’re describing.

How would you describe our relationship with the looming ails of our planet?

I think we live in a time where disaster is omnipresent, both as a function of our information ecology but also because climate change, in all its varied and diffuse manifestations, is now visible everywhere as an extreme or as a distortion of the normal. But because of our privilege and positioning, most of us will find it possible to regard catastrophe from a distance, to intellectualize it and normalize it — and when it happens to come uncomfortably close, to use our resources to sidestep these consequences in a way that many in marginalized communities are unable to do. There’s an analogy here to the way in which we worldbuild around this catastrophic presence in literary fiction, privileging a default reality where the landscape holds still to allow greater focus on the humans moving around in the foreground. A landscape that’s only there to provide tonal notes or perform Barthes’ “reality effect” is nothing like the intricate, changeable, precarious terrain that I recognize in the west, and only furthers the illusion that land is the backdrop to anthropocentric action. In the novel, I wanted to bring play with this metaphor of the old studio backdrop, bringing the flat image uncomfortably close to the human actors, populating it with smoke and fire and other urgencies, pushing the narrative eye into that flattened space to show its dimensionality and wander around in the hills and grasslands tracking nonhuman agents of all different kinds. At the same time, some of the foreground plot material reveals itself to be trompe l’oeil — Patrick’s big Hollywood break working on the set turns out to be a dead end, the green screen on set is never going to be filled in by virtual images and spaces, many of the characters’ paths forward are just painted walls.

Both the novel and this response intimate a fraught relationship between the film and tech industries in Los Angeles and the landscape that surrounds them. Famously, film producers came out to Hollywood in search of consistent good weather so they could make films year-round, but ironically in the novel this once stable landscape is disintegrating. Additionally, the novel seems to skewer capitalist logic and parody the California tech industry with the immediate widespread adoption of WAT-R, a purported equivalent to the ubiquitous liquid.

What attracted you to Los Angeles as a setting for the novel? How would you describe the changing economic, artistic, or physical landscapes of Los Angeles?

In the past, I’ve written about places that are “everywheres” or “nowheres”: suburban neighborhoods, grocery stores, warehouses and hotel conference rooms, and dreamlike archetypal spaces that are more like the inside of my own head. So of course on some level I was interested in writing about Los Angeles, since it’s a place that embodies both extreme particularity and extreme generality, one of the most heavily mythologized places in the world and the most filmed — particularly if you count all the times when Los Angeles appears in disguise, as someplace else — but also one that is large and sprawling, full of nooks where storefronts and structure from decades past can survive undisturbed and unmodernized into the present day. It’s a place where specific ethnic communities can find space to themselves and make their neighborhoods over in something like their own image — like the pocket of the San Gabriel Valley I lived in where signage in Mandarin and Spanish eclipsed English. The overwhelming bulk of LA is not the LA of establishing shots and filming locations, but of interesting, varied, specific places that never make it to the screen and therefore never attain recognition. It’s a city with a vast and underdescribed subconscious, and strange, surreal eddies where the high scrutiny of the city’s most recognizable locations drops away sharply and it feels like you’re nowhere at all.

The ecology of LA embodies a similar paradox, an anywhere that is in actuality highly particularized. I love what you pointed out about the predictable good weather, how it’s been a draw for the film industry and civilians both, but the sameness of the weather and the apparent plasticity of the landscape — that you can grow citrus there if you have enough water, almonds if you have enough water, lush green lawns if you have enough water — masks a more stringent set of principles beneath. Water is the substance that makes everything feel infinitely possible and infinitely changeable, but when we rediscover that water is finite, it’s like waking from a dream and finding ourselves in a strange and rigid new place, one whose logic reintroduces vulnerability to the body of the observer.

I love what you said about discovering that even water is finite. I keep returning to the novel’s epigraph from Toni Morrison, “All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was,” in part because it so beautifully complicates my interpretation of the famed John Keats epitaph, “Here lies one whose name was writ in water.”

I’m curious why you chose to include this epigraph, and how it might relate to the understanding of water you developed while writing this novel.

I love that Toni Morrison quote too, and love how it resituates our understanding of water within a vastly expanded timeframe. The quote comes from a talk Morrison did where she speaks about the human effort that went into making the Mississippi River something predictable, straightened out, offering more stable land for homes and acreage. The Mississippi as we know it was manufactured, its manageability is an illusion maintained by labor and dredging and levees and dams — and this dovetails, in fact, with an interesting argument from a book by the landscape architect Dilip da Cunha that in India the notion of a river was an imposed, colonial construct that turned long-established, naturally variable wetlands into zones of approved waterflow and dangerous “floods” that needed to be contained. The labor we put into containing our environment is often invisible, either because the infrastructure that enacts it operates out of sight or because we are too habituated to the effort to perceive it. Morrison takes the long view, that the return of water to areas of exclusion is no aberration, but a reassertion of the land’s deeper form, a way of being that can never be wholly erased — and it works as a metaphor for the individual, for writing, for the way that reality insists upon itself, inconvenient and unruly.

To me, Morrison’s insight is also one about agency and animacy: that water isn’t some inert substance we can shift at will, it’s an extended, motile thing, organismal in the way it relates to and entangles itself with the rest of the world. So the introduction of some new water substitute, manufactured and not-quite-identical, is not a simple addition to the water system but a profound disruption. From the fixed perspective of one Heraclitan individual, water is always moving, changing, structureless, but in a larger framing it has a permanent and structural relationship with our bodies and minds. It’s WAT-R, the newly made and incompatible substance, that truly has no memory, and whose specific structural differences disrupt the individual’s ability to recall who or what they are.

Toward the end of the book, Patrick says, “I need the ground, I need to feel it. It’s the only thing I have. I’m not sure of anything anymore, I can’t know that it’s there if I don’t have my hand on it.” A few pages later his wife Alison prays, “I want to live in the world, not upon it. I want to live in reciprocity, not exchange.”

Both these quotes gesture toward an underlying Cartesian anxiety and growing sense of dissociation with the Earth. What interests you about this feeling?

I think you’re absolutely right, it’s both a Cartesian anxiety about what can be known with certainty about the world via the materiality of the body and it’s also a cultural, psychological anxiety about the distance that we encounter between our habits and impulses and the workings of a natural world that appears whole and unalienated. If you trace both anxieties far enough back, they converge in a feeling of separation and lonesome individuality that I think is worsened by the way neoliberal capitalism defines the individual as a consuming, choosing unit, self-determining within an overdetermined socioeconomic landscape. I’m interested in describing the emotional dimensions of these anxieties, cataloguing these private and difficult-to-discuss feelings of futurelessness and homesickness, and thinking about the yearning to reenter the world and all the effort, both individual and communal, that it might take to do so. Increasingly, in the framing of biologist/cyberneticist Jakob von Uexküll, it feels like the different semiotic processes within our organism that constitute our umwelt don’t add up to a whole picture, that the picture we have is continually disrupted by shifts in scale and tone and register that challenge the larger sense of being placed in the world. I wonder if stretching existing modes of representation, artistic and scientific, can help to close some of those gaps or at least point out clearly where they are. But it would probably be better to just change our lives.

While the novel’s content has an obvious facility for film, the novel’s form appears to as well. The dialogue is tense and quippy and many scenes open with strong, kinetic opening images and end with panoramic descriptions of the Californian landscape.

How has film influenced your writing, and the composition of this book in particular?

I think many people writing today are influenced by the rhythms and ratios of screenwriting — there’s such an understanding in today’s TV and film of the shape of the human mind, its attention span and appetite for focus and worldbuilding and surprise, and for better and for worse I think we’ve internalized a lot of these lessons. Which is a shame, because the moving image is such a profoundly inhuman medium, when you look at it apart from the way we use it, you might see more in common with machines or on the other hand with the patterns of light falling through moving branches and onto a rock. Which is why I admire works like Claire Denis’ sci-fi slow burn “High Life” and Lynch’s underloved third season of “Twin Peaks” for reintroducing fragments of Real Time and Real Space into mediums that often give the impression that all the universe is made of fun-sized components. The main cord of my novel is constructed in scenes that try to be appetitive, snacky elements, but the narrative eye drifts away from them to include people in the background of the story, forgotten subdivisions, and lots of dry, elemental terrain unpopulated by human beings. By the end of the book, there’s no cord, just individual fibers. The form is driven by the question: What’s outside of satisfaction, what’s outside of interest or attention, what is the larger world we’re missing when we’re attending to any one element of it?

How can we as readers and citizens of the world see the larger world we’re missing? What thoughts has writing and releasing the book left you with, and what thoughts do you hope it leaves us with?

I don’t know if it’s possible to see the whole world that we’re missing, but the first step might be denaturalizing the personal sphere, taking what feels natural and immediate about it and trying always to link it to that which is extrinsic, causal, and complex. I think it takes developing a relationship with the land around you, wherever that might be, and learning to appreciate the changes and transitions of the landscape on its own temporal scale, rather than our default clock. I think a body, even a human one, is in a profound relationship to the inhuman, and that we can find a better connection to the earth by thinking of ourselves more as animals, with an animal’s grounding in bare life. That feeling, of being rooted in existence, is a type of critique in itself. I left this book feeling that I had put enough down on the page to convey how this moment in history, and the coming one, feel to me — if it is overwhelming, it should be, because we’re experience the profound destabilization of a climate that has been our home, and a good one, for thousands of years. What I want to think about now, and what I hope readers ask themselves after the book is over, is what type of world they’d rather live in, what type of world they’d want to make. When the world feels most debased, most razed and leveled, it is also an invitation to build something better, or to reimagine building entirely.