Natalya Sukhonos’ poetry takes you gently by the hand and then pulls you in. Her poetry drops out of the sky and then grinds to a halt at a near-car crash in New York City. Most of all, Sukhonos’ poetry asks you, the reader, to listen to a roar that is silence.

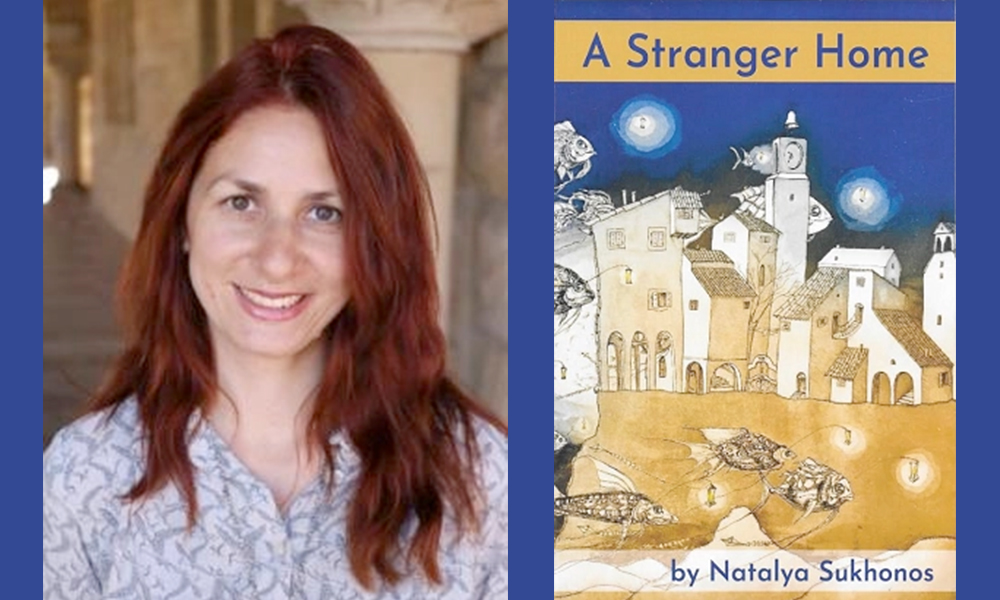

A scholar of 20th Century Russian and Latin American literature, Sukhonos teaches at the College of Interdisciplinary Studies at Zayed University in partnership with the Minerva Project. Her first collection of poetry is Parachute (Aldrich Press, 2016), and her latest collection is A Stranger Home (Moon Pie Press, 2021).

Sukhonos spoke to me from her home office in New York. It’s a room with bright yellow walls, a painting by one of her young daughters pinned to the door, an open closet with clothes peeking out, a pile of books and papers, a framed photo I can’t quite decipher. A vibrant, busy room that is almost as surprising as Sukhonos’ poetry.

¤

JOANNA CHEN: You were born in the Ukraine and immigrated to the US many years ago. What, rather than where, is home for you?

NATALYA SUKHONOS: One of my favorite rock musicians, Boris Grebenshchikov, in the lyrics to one of his songs, said that “love is a way to return home”. I really identify with this. Home is certainly where love is, and yet I would say that the obverse of the feeling of home is estrangement. For me, they go together, so home is thus a source of both comfort and tension.

How do you relate to the Ukraine today?

My relationship with the Ukraine is nostalgic. I left the Soviet Union when I was nine and a half. I have memories of strolling under chestnut trees in Odessa with my grandfather, going to the sea, spending time at a dacha with my parents and grandparents and my great aunt, eating apricot ice-cream. Mostly I think of Odessa, a city built by French and Italian architects in the 19th century, and just being filled with a beauty that is very fleeting and effervescent, people walking through the grand boulevards that were probably inspired by Paris.

Do you believe in the concept of a mother tongue?

I’ve spent the majority of my life in the US. I am bilingual, but I probably speak more English than Russian at this point. Despite this, I do believe in the idea of the mother tongue. All of my life outside of the Ukraine I’ve tried to maintain my Russian very consciously. I feel it’s a huge part of my childhood, and I associate it with being able to say really intimate things, to reach back to who I really am, or who I was back in Odessa, strolling under those chestnut trees.

Why Russian and not Ukrainian?

I grew up in Odessa, a multilingual, multi-cultural city with a sizable Jewish population that aligned itself with Russian more than Ukrainian. This was because Russian served as a lingua franca for speakers of Yiddish and Turkish, Italian, Greek, and Ukrainian alike. Russian was also appealing to Jews because there was a lot of anti-Semitism among Ukrainians. I grew up speaking Russian and this is why I consider it my mother tongue.

My husband learned Russian while he was dating me and now he’s fluent and we’re raising our children bilingually, which I think is fantastic. The other reason I think I’m so passionate about Russian is that I’m an academic, a lover of literature. If I hadn’t been able to maintain my Russian and speak it as well as I do, I wouldn’t have been able to master Anton Chekov or Fyodor Dostoevsky or some of my favorite poets such as Anna Akhmatova. It’s really important for me to be able to read in the original. For me, those works really express who I am and every time I read them, I rediscover myself.

Your poetry collection sits on the intersection of fairy tales, the fantastical and bald reality.

This poetry collection came together organically after my mother died in 2017. It isn’t that I sat down and said, I’m going to create a lots of poems about my mother’s death, I used poetry as a way to process her death and my grief. It was really difficult. That was the reality part. The fairy tales and the fantastic were a way for me to approach some questions that I had and still have on what death really is. What happens to the body as it loses its senses and enters a different realm? Is there a soul? Where does it go?

Fairy tales and the fantastic really have to do with a different way of looking at the world. It’s a way to recontextualize reality. My favorite writers, including Jorges Luis Borges or Julio Cortázar, take the everyday and make you look at it in a radically different way. Julio Cortázar has a short story called “Axolotl” about a man who stares at a tiny lizard through the aquarium glass because he’s lonely. At the end of the story, you suddenly realize he’s become that lizard.

I’m interested in that slippage between stark reality, harsh emotions like loneliness and grief, and what can be imagined. The fantastic could be an escape, but I don’t want to look at it that way.

What role does memory play in your book?

I think memory is another way to construct a narrative. In Vladimir Nabokov’s Speak, Memory, we read about the extraordinarily prodigious memories of his childhood, full of these beautiful optical illusions and monochromatic landscapes created in his mind. After a while you understand memory is a construct of the imagination, that memory is another way to tell the story. I tried to play around with that a little bit in a couple of places in this collection. The first poem, “Parachute,” is about my grandfather who was an air trooper in WWII. The poem narrates what it must have been like for him in the war and to have made these jumps 94 times.

These are vignettes of his life but also of the Ukraine and the experience of immigration. The poems consider my own memories of Odessa and also my mother’s memories, in which I have to actively decide whether these memories are constructed or not. There are also poems about my great aunt, who brought me up, so these poems are about the Holodomor, the manmade famine in the Ukraine, which she had to endure, in 1930… and these poems play around with memory because they narrate her experiences. I’m considering what her memories must have been like, so I take her stories which she told me many times over, with the tendency of an older person to retell the same story, adding and taking away details, not always being consistent. I think memory is a way of making craft more physical and a reimagining of other peoples’ experiences.

One poem I particularly enjoyed is “The Fragrance, the Garden”, in which you write:

If all the plants

are quiet I can hear

words flicker

in the glass

behind the garden.

I can hear water

thirsting for itself,

a hand wreaking havoc

with metal and twine.

The whole collection, in fact, is teeming with noise — not the kind of noisy noise we are used to but what might be termed quiet noise. Your tendency toward the fantastical prompts you to hear sounds that the human ear cannot pick up. The roots of a tree growing, water thirsting for itself, light warming our veins. What on earth does this sound like? It’s interesting to me because you’re asking the readers to actively listen with their imagination.

It might have something to do with the fact that I grew up in a loud Ukrainian Jewish family. The more disturbing aspect was you couldn’t really have quiet, there was always a lot of laughter, a lot of toasts, people interrupting each other. I think somehow it slipped into my poetry.

Invisible sounds have to do with life that still flows, that still happens, in spite of disruptive events that might make it seem as if life has stopped, like immigration, the loss of love, a moment of loneliness and, of course, death. I think that’s part of it and I think the other part is that I am interested in these in-between states of mind where you have strong emotion but you don’t necessarily have the words to describe it. Paradoxically that’s where poetry comes in. It’s apophatic, as used to describe mystical experience, like St. John of the Cross in The Dark Night of the Soul, and used a lot of negations to describe the experience of ecstasy that he experienced. I’m not necessarily writing about ecstasy, but I am writing about trying to reconstruct memory, about moments of death and what it must be like. I think I might be unconsciously filling these moments with sounds to make the reader understand that something is going on, we can’t quite put our finger on it, but there is a music to it. We can listen to the unknown and it will manifest itself.

In an email prior to this conversation, you said you’d like to talk about exploring the ways in which your poems touch on what’s hard to articulate. These thoughts reminded me of Adrienne Rich, who wrote that “a poem is a construction of language that uses, tries to use everything that language can do, to conjure, to summon up something that’s not quite knowable in any other way.”

You’ve given me a lot to think about. Essentially, there’s a paradox here — some things are difficult to describe, but precisely because they are difficult, poetry might be the best vehicle to describe it.

I’m thinking of that line in “After the Rain” from your collection: “Poetry is the harried man your car missed by a few feet.”

I remember reading the surrealist novel, Nadja, by André Breton — beauty was a way to render this electric state of shock that the speaker was talking about. I remember reading this and getting this strange idea that an aesthetic experience might be an asymptote, a mathematical function that gets close to the absolute but doesn’t quite get there. This is what’s so alluring and interesting about language and poetry as a way of manipulating language in a particular way. It’s funny you mention that particular line from my poem, about the man leaping out from the bus stop and into this poem, because that came from a really traumatic experience for me.

I only learned how to drive three years ago. The poem was conceived when I was driving home after yoga, and I almost ran this guy over, who was running toward my car. I had to write a poem about it, to transform that horrible experience into something else.

Something beautiful emerged from that horrible experience.

That’s really what poetry is for me — it seems to have an almost alchemical quality of transformation. This is because poetry is a puzzle. My younger daughter, who’s two years old, loves jigsaw puzzles. Sometimes I think of poetry precisely as such a puzzle. How do we put lines together a way that creates the most interesting effect? How do we play around with sounds? Even as we approach somber things, these things that cannot be said, we should still retain that sense of play.