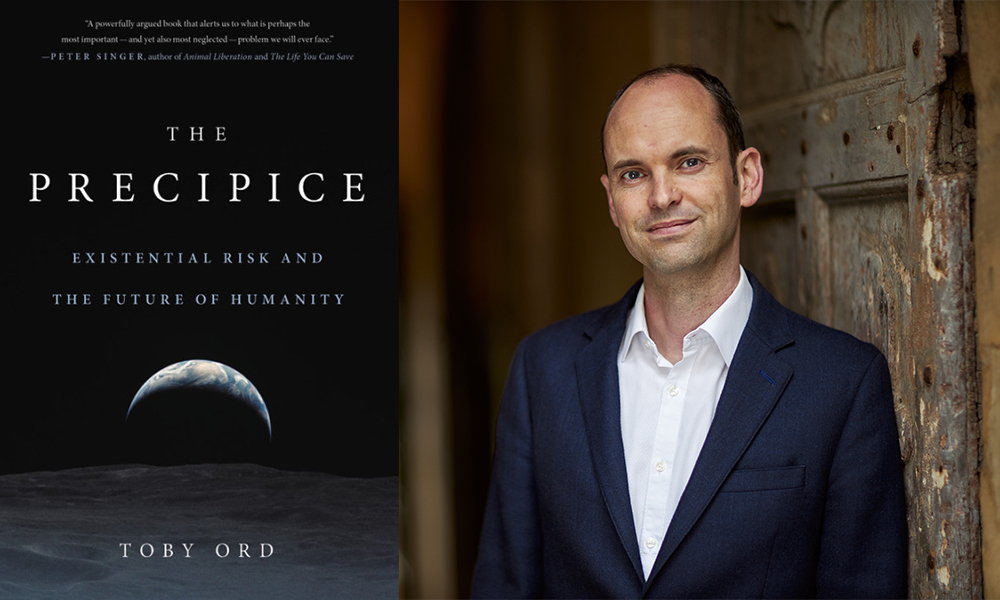

Which existential risks do we have to address as quickly as possible, and which as carefully as possible? Which risk factors won’t bring about humanity’s demise, but could make us much more susceptible to such threats? When I want to ask those questions, I pose them to Toby Ord. This present conversation focuses on Ord’s book The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity. Ord is a philosopher at Oxford University, and has played a pivotal role in the effective-altruism movement. Ord’s work on the ethics of global health and global poverty led him to create the international society Giving What We Can, whose members have pledged over 1.5 billion dollars to highly effective charities. He has advised the World Health Organization, the World Bank, the World Economic Forum, and the UK Prime Minister’s Office and Cabinet Office. His current research focuses on the long-term future of humanity, and on risks threatening to destroy our entire potential.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Typically we tell kids to stay away from the precipice. But for the precipice of this book’s title, a barely adolescent (one hopes) human species will need to take certain crucial steps beyond just restraining itself from falling off the cliff. So in terms of both the dangers before us, and the decisive (sometimes quite deliberative) engagements demanded of our societies over the next several centuries, could you introduce some of the biggest challenges which will manifest as state risks (needing to be met as fast as possible), and some which will manifest as transition risks (needing to be managed as sustainably as possible)?

TOBY ORD: Throughout our two hundred thousand-year history, humanity has always faced risks, particularly natural risks such as asteroids. Only in the 20th century, with the atomic bomb’s development, did humanity’s power grow so great that the risks we posed to ourselves (the anthropogenic risks) rose above this background of natural risks. Crossing that threshold took us into this era I call the precipice. And as you suggested, I think of this precipice not as a cliff that one can and should pull back from, but rather as a uniquely dangerous span in humanity’s journey. You could picture us walking along this narrow ledge, with a cliff reaching up one side and a precipitous drop on the other. We can’t quite calculate our chances of falling, but we know that we’ve never encountered a more dangerous period — the most dangerous, I believe, that we ever will encounter.

Nuclear weapons formed the first of these self-imposed risks. Human-induced climate change has brought on another. Over the coming hundred years, I think we’ll see risks from engineered pandemics and unaligned artificial intelligence. Risks will start arising at an ever greater pace, because they’ll stem from humanity’s increasing power. Over the previous several centuries, we’ve experienced exponential increases in power without corresponding increases in humanity’s wisdom and ability to protect itself or its long-term potential.

Alongside this historical axis (now showing, as you say, an acute uptick in self-imposed existential threat), could you also place the growing gap between our tech-infused power and our civilizational maturity on a philosophical axis: requiring us to recognize that life-enhancing technological innovation perhaps always brings with it new potential vulnerabilities, always necessitates picking up new preventative responsibilities — new commitments to identifying and preserving what we most value?

Increasingly powerful technologies create unique risks for humanity’s entire future. But they also bring with them many, many benefits. In fact, we know that technology’s benefits, taken as a whole, have far exceeded the everyday risks that come along with it. Despite all of the risks to human health, for example, life expectancy has grown consistently over the past several hundred years. Despite all the risks for financial ruin that come with new technologies, our wealth and income have continued to grow. What we don’t know, however, is how to address the small likelihood of very severe outcomes. We haven’t had enough generations of technological progress to know what the once-a-century events look like, and how extreme the effects might be.

This book does not claim that new technologies inevitably pose such significant risks as to make these technologies bad on balance. Instead, the book attempts to acknowledge those benefits, while also considering other potential consequences, and less obvious risks, and more cautious approaches we might pursue when developing these technologies. We often push our best and brightest people into developing new technologies, with little emphasis on managing these emerging technologies, and making sure we don’t face catastrophic outcomes. But this book suggests that a more mature humanity would in fact devote just as much time and intellectual talent to governing the rise of future technologies as we do right now to developing them.

To further flesh out then this book’s range of existential risk, could you offer a few scenarios that don’t necessarily involve the eradication of our entire species, but instead irrevocable civilizational collapse, irredeemable dystopic rigidification, or irretrievably lost collective potential?

Human extinction remains the most striking and most graspable form of existential risk. Such extinction would destroy not just our present, but humanity’s entire future. It would cut off all potential for everything we could have achieved over thousands of generations to come. But other outcomes also could erase this potential.

Consider a world in which a large catastrophe has collapsed human civilization and ruined the environment, making it impossible for us ever to rebuild civilization, reducing us forever to the status of foragers. This would drastically narrow our once-soaring potential — to very meager options. Or consider a world in chains, where a totalitarian regime has risen to global power and enslaved people into extremely constrained lives. Again this could destroy the potential for humanity ever to get out of such a situation. That may still sound technologically impossible for now, but not much would need to change from certain trends we see today. The key point is that, while the future for now looks so much bigger and better than the present, we shouldn’t consider it an inevitability that we will fulfill this potential.

Your discussion of climate change, for one example, departs from some existential-risk conversations which might seem to minimize this danger — since you see climate change, even if not threatening human survival, certainly threatening human potential, while also leaving us more susceptible to any number of natural or anthropogenic risks. So could we take climate concerns as one representative example of the increasingly salient threats posed by circumstantial lock-in: drastically reducing human ingenuity, human prospects, and human resilience?

I do hear increasing discussion now of climate change as an existential risk, severe enough to threaten humanity. When I started writing this book, I thought I could rule that out. I assumed I could rule out immediately the runaway greenhouse effects that have reshaped Venus. But I found that, while some very good papers, published in very good journals, argued against any such possibilities for Earth, you couldn’t say the topic had been conclusively and scientifically settled. Closely related scenarios of so-called moist-greenhouse effect (where temperatures might increase by tens of degrees Celsius) remain quite hard to rule out. And the more I read on these subjects, the more I recognized that even the IPCC’s standard climate models do not rule out extreme scenarios, with warming by much more than six degrees, maybe even by 10 degrees Celsius. We don’t talk enough about these unlikely but possible scenarios already present in today’s climate models.

Yet I find it difficult to imagine climate change, even at very severe levels, destroying humanity. It no doubt could bring terrible human and environmental catastrophes on a scale we’ve never seen. But in terms of existential risk, it’s unclear what climate mechanism would cause immediate human extinction or collapse of civilization.

Still, when we try to factor in highly unpredictable changes to the global environment occurring at an unprecedented scale and pace, we can’t be more than maybe 99 percent sure of humanity surviving a very severe warming event. And on top of that, as you suggested, climate change presents a complex risk factor that exacerbates other risks. If we spend the next century under constant pressure of changing climate, squabbling at the international level about who has the responsibility to do what, that stress on the global community will leave us less prepared and less resilient when addressing other events. So in terms of existential risk, climate change’s role as a risk factor looms even larger than the direct risk it poses.

Could you offer a couple further examples of how risk factors shape the biggest threats we face?

When discussing existential risks we often divide them up into silos. We think of particular threats from an asteroid or a comet, a supervolcano, a pandemic, artificial intelligence, climate change, and so on. We ask ourselves: “How much risk do we face of this one particular thing destroying humanity’s potential forever?” We classify people working on one of these specific dangers as working on existential risk, and people working on broader civilizational challenges as doing a different kind of project. But the more I thought about it while writing this book, the more I recognized various cross-cutting factors, which may not by themselves pose existential risks, but which increase the overall level of that risk.

Great-power war gives a good example. Great-power war provided the background for the atomic bomb’s development, and great-power friction provided the background for the Cold War’s nuclear escalation. That escalation substantially exacerbated the existential risk. And if you ask yourself today “How much existential risk will we face over the coming century?” you would have a much less worrisome answer if you could rule out great-power war. Perhaps one-tenth of the risk would disappear.

Another risk factor could come from mass unemployment, for instance with artificial intelligence displacing much human labor. Economists debate whether in the future, as in the past, new forms of automation also will lead to new kinds of jobs, with the overall unemployment rate staying pretty stable — or whether we might enter some fundamentally new era, in which we automate not just physical labor but also intellectual labor, leaving little labor for humans to do. If that more radical kind of change does occur, we might see extreme tensions in the geopolitical landscape, with nations finding it difficult to determine what their citizens should do, and how to support those citizens no longer earning wages. Who knows what types of radical policies distressed nations might consider, and opportunistic politicians might demand? If you think back to 20th-century experiments with communism and totalitarianism, you can’t help wondering what new ideologies might emerge in an attempt to deal with such major social changes, and again how various social pressures might reduce humanity’s capacities to confront particular existential risks.

You had mentioned challenges of AI alignment, the difficulty of designing an AI that (when detecting divergence between its goals and ours) recalibrates in accordance with our aims — rather than overcoming us in instrumentalized pursuit of its own aims. Could we also bring in the disarming prospect of a nonaligned AI not even needing to dominate humans Terminator-style, if it can simply manipulate us in ways impossible to predict, exploiting civilizational weaknesses we don’t even recognize? And could you sketch where today you see the most promising, most frustrating, and most unnerving developments in the field of AI alignment?

Right now, humanity has control over its destiny in a way that other species on Earth do not. Chimpanzees, a comparatively intelligent species, nonetheless find themselves fundamentally at the mercy of humans — as do most other species. How did humanity get to this position of controlling its destiny and the destiny of so many others?

That advantage comes not from our physical abilities, but from our mental abilities. This combination of our general intelligence, our ability to learn, and our ability to communicate and cooperate with other humans has brought us to a level of increased power, where we ourselves can determine whether or not we fulfill our potential. But advanced AI may change all of that. A 2016 survey given to more than three hundred top machine-learning researchers, for example, asked when an AI system would be able to accomplish every task better and more cheaply than human workers. On average, they estimated a 50 percent chance that this would happen by 2061, and even a 10 percent chance of it happening by 2025. An AI system outperforming human workers at almost every task inevitably will have surpassed us in its cognitive abilities. And so we would need to wonder how humanity could remain in control of its own future. Would we already have ceded this power to such a high-performing artificial-intelligence system?

I think that offers the best high-level way to begin looking at these concerns. You might think that we just have to figure out how to maintain control over these AI systems, that we just have to give them the right instructions to follow, give them goals aligned with ours — so that in building their ideal world, they build ours too. But the people directly working on alignment questions have found this much more difficult than we might have thought. The people working on alignment have in fact provided some of the leading voices of concern about existential risk. So that does worry me.

Here again though, even as we seek to avoid lock-in scenarios and dystopic outcomes, the precipice doesn’t just leave us to ponder whether we dare disturb the universe. The precipice demands that we do act. And since, by definition, attempts to anticipate and prevent existential catastrophe must operate from a real-world sample size of zero, must succeed without recourse to second chances, what distinct challenges does a scientifically minded, pragmatic, liberal-democratic society face — say in recalibrating certain institutional mechanisms to proceed from a principle of proactive foresight, rather than from a more deliberative sifting of lower-stakes trial and error?

Humanity has done a great job of learning through trial and error. This approach gives us a substantial number of data points to help determine how things went wrong. We can sift through the ashes and work out which elements need improvement. Through error, say in a political context, we can cultivate the collective will to make significant changes — because people can see how bad the current state has become, and develop a strong desire to move to something better. But existential risks, by their very definition, do not allow us to learn from our mistakes in this way. If we suffer an existential catastrophe, we lose any chance to do better next time, because we won’t have a next time. So we do need to learn to deal with and manage these challenges without relying on trial and error. We’ll have to develop political will without salient examples from our parents’ generation ringing in our ears.

More specifically, from a scientific perspective, experimental data often comes really from trying something time and time again. To assess a relatively unlikely outcome (a one percent chance, for example), we still might run hundreds of trials. Perhaps you need at least one thousand opportunities, with at least ten of these outcomes, before you can start to pin down the real probabilities and their broader implications. But we just can’t help ourselves to those kinds of scientifically established probabilities here. We need to work with evidential probabilities — probabilities relying on the best available evidence, and using a certain amount of inductive reasoning, and applying some forward thinking. That means a much less studied and less certain kind of conjecture. Scientists have less familiarity and less comfort with this kind of thinking. It definitely runs its own risk of overreacting. And if you really take to heart this assumption that we can never fail (not even once), that of course might lead to cases where our institutions protectively overreach: without us even recognizing it, and with our potential now diminished in a different way. So really I do consider this an enduring challenge.

Related organizational and institutional challenges arise at every level: with a collective-action problem potentially sapping the initiative both of individuals and of entire nations, with market mechanisms poorly equipped to promote the public good of existential security, with no adequately resourced international agency to address incipient threats, with regulatory approaches potentially leaving the riskiest decisions to the least compliant actors, and with disjointed ad-hoc scenarios dictating who among us decides which elective existential risks are worth taking in which distressing circumstances. So what additional kinds of redesigned social coordination do you see us needing if we hope for our collective decision-making not to fall desperately behind the pace of technological innovation?

Managing existential risk (ensuring we never once fall victim to such a catastrophe) will require significant institutional innovations. Only through these new institutions can humanity on the whole gain the wisdom and prudence and patience we’ll need to navigate the precipice. Precisely which institutional changes will help the most remains to be seen. But for one specific angle here, I like to stress, on democratic grounds, that most of the people affected by actions our governments take today are people who can’t vote — in some cases because they’re children, but for many more because they haven’t yet been born. We know, for example, that our action (or inaction) on climate change will affect people for centuries to come. Yet that huge portion of humanity gets no voice in these present discussions.

Now, of course, we face immense challenges in trying to give those people a voice today. We can’t ask them their opinion, and we can’t let them vote. But we don’t even make an attempt to represent their interests. We could set up, for example, certain ombudspersons for giving future generations some kind of representative voice, some form of soft or hard power. You could imagine seats in the US Senate or the UK House of Lords set aside for ombudspersons representing future generations’ interests, with institutional mechanisms for holding those in these seats to account. Some countries have already experimented with constitutional changes to ensure representation for these interests.

Even if we can’t say precisely how these future generations would balance quality-of-life improvements through quickly developed technologies, against long-term survival through sustainably developed technologies, in some cases we actually have a pretty good idea. With climate change, for example, we have a very good idea that people of the future would want us to act much more substantially than we are right now. But we lack institutional mechanisms for taking those likely interests into account.

Here your book seeks to clarify thinking around some of these medium-term calculations in part by pointing to a “longtermist” approach — a more imaginative and expansive and ultimately effective altruism premised on humanity making its next major step in moral progress, by recognizing the equal value of individuals not just across distance (from one community or one country to another), but across time (potentially from one millennium to another, and again with the far disproportionate number of generations hopefully still to come). Could you describe how we might best conceive of (alongside institutionalizing) this far-reaching, future-tending form of compassion?

We don’t often think this way about ethics: about effects not just on the people immediately before us, or on people all over the world right now, but on the entire long-term future of humanity. But I do see such a longtermist approach to ethics as a necessary step for us to make soon — to start taking seriously that the people still to come don’t count any less than we do. I describe this as the taking on of the perspective of humanity, of not just asking: “What should I do?” or “What should my country do?” or “What should everyone in the world today do?” Alongside those very important questions, we also need to start asking: “What should humanity do? How would a wiser humanity act on these issues, by taking into account all the generations that have ever lived, and the entire lifespan still ahead of it?” Adopting that perspective can help us realize the rashness in risking this entire sweep of human potential just for some very fleeting gain.

Similarly, as one constructive means of steering us away from lock-in scenarios, The Precipice seeks to envision the most galvanizing possible futures. Your book traces, for example, a philosophical pivot away from policing certain wrong actions or bad outcomes (specifically in a world of scarce resources), towards embracing a cosmically expanded sense of both spatial and temporal scale, of barely imaginable quality of life, of yet undreamt possibility, and even of redemptive destiny (were humans to end up saving a biosphere of the future, rather than just destroying our biosphere of the present). So could you make concrete the understated yet perhaps revolutionary premise here that “In optimism lies urgency”?

Sometimes when people hear what I work on, they’ll ask: “How do you cope? How do you not get overwhelmed by all of these depressing possibilities?” But doing this work actually feels very different from that — it gives me a profound sense of optimism. For it allows a glimpse of humanity’s enormous long-term potential. We could last for a truly extraordinary amount of time. If we last as long as a typical species, we would have about a million years left. But we might end up lasting much longer than that. Some species have lasted for hundreds of millions of years. And we could last longer still if we find ways to move beyond the Earth and reach other star systems. We would have so long to perfect the technologies to accomplish this goal, if only we can take the hardest step by surviving the next few centuries.

Then in terms of spatial possibilities, we already know of one hundred billion stars in our own galaxy, and billions of galaxies beyond that. So here again human civilization might have just barely begun. Or in terms of the quality of human life, placed on this much grander scale, you could start with how humans increasingly have removed the presence of pain from our lives, through the development of anesthetics and painkillers. We could remove far more of these negatives from our lives, and we could cultivate much more of the positive. Peak experiences in our lives already so surpass the day-to-day experiences. And those peak experiences also point to what everyday existence could be — with whole new ranges of peaks. So it really seems that almost no known limits exist (from physics or biology or psychology) for how good our future could be.

Here we approach post-precipice stages of the “Long Reflection.” And here I wondered if you could trace not only some furthest possible parameters of that reflection, but also its pace — a bit less anxious and urgent one hopes, a bit more slowed down and deliberative, with our existential security much better secured, with the game now “ours to lose.” How might this Long Reflection prove not just infinitely more productive, but also more relaxed?

The central task of our own time involves achieving what I call existential security — both to avoid the current risks, and to put in place mechanisms that can safeguard humanity’s future in a lasting way. But once we achieve existential security, we would have a truly vast amount of time to work out what we want to do with our potential. We wouldn’t have to rush and just pick the first thing that comes along. And we’d have serious choices to confront. If we could leave the Earth, we’d have to ask: “How should we govern this expanding number of planets?” If we could alter our bodies and our basic ways of being significantly, we’d also have to ask: “Do we want all humans to share certain qualities, or do we want to allow them to change in a diversity of different ways over centuries or millions of years?” If we got those answers wrong, we could, again, squander some of our potential. But we’d face no panicked rush to leap into these answers. We’d have a long time to reflect upon the best realization of our potential. I think of this as the second step in humanity’s grand strategy, and I call it the Long Reflection. This period could last for centuries.

Many of us might have other projects to pursue, rather than the Long Reflection. But we would have a public conversation that people could join and participate in if they wished, where we’d try to understand the limits of what we have available (as well as how we should proceed within those limits), and to what extent we want to create a unified future (or let a liberal diversity of futures unfold), and whether we need some kind of constitution to ensure these different civilizations don’t become warlike and seek to destroy each other. We’ve just barely started to think about these fascinating questions, which I consider a crucial (if less immediately pressing) area for sustained thought and discussion. For now though, we do need to prioritize keeping our potential intact over the next several generations, so that we can survive to have this kind of conversation.

Returning then to this book’s basic orientational question of “How can we act…when we are not fully aware of the form the risks may take, the nature of the technologies, or the shape of the strategic landscape at the moment they strike,” could you sketch the current need for a disciplinarily diverse range of experts to cooperate on minimizing our semantic ambiguities, on more precisely comparing various long-term prospects, on directing and implementing the most effective possible resource allocations?

We are still in a very early stage of thinking about these issues. These risks came to our attention with nuclear weapons in 1945. People immediately began asking some of these questions, but with the sole focus on nuclear weapons. Then, with the Cold War’s end, a lot of this attention on risk went away. Then it started coming back with climate change, but again just focused around that one particular risk, with very little consideration of how to compare risks — or to understand the landscape of mutually interacting risks, or of future risks. But to act effectively, we need to think more holistically about existential risk.

In 1996, John Leslie published his fantastic book The End of the World, which offered the first serious attempt to formulate how these various risks of human extinction all fit together, and how to address those risks. In 2002, Nick Bostrom broadened these investigations by introducing the idea of existential risk, which covers all catastrophes that would irrevocably destroy humanity’s potential — including, alongside extinction, permanent collapse of civilization. But these lines of thinking and categorization still remain in their infancy.

I’ve tried, in this book, to bring together a lot of the best thinking already out there, and to show readers the types of insights and categories and conceptual tools we already have. I hope some of these tools will feel quite obvious, at least in hindsight, and that readers will think: I could have come up with that — and I have ideas to contribute to this conversation. This field might at first seem unapproachable, but I highly value many different ways to bring together small insights and innovations in our thinking on this most challenging of predicaments. I think that kind of collective project can greatly improve our situation, especially to coordinate efforts on all these different risks we face.

Well, with coordination still in mind, I can’t help pausing on possibilities for the cosmic endowment not necessarily to get cashed in solely by our one species. So to follow up on a few topics: where might mutation and other pressures on species unity sit alongside questions of existential risk? What to say about humans potentially outlasting mammal species’ typical lifespan, but maybe not the trillions of years this book posits among the possible? And how should we hold together these entwined concerns of possibly losing our most essential human qualities, but also of possibly failing to fulfill our potential if we don’t keep evolving, but also (if we most ardently wish to promote “flourishing” writ large, rather than just to promote “us”) of possibly fostering the future flourishing of entities quite unlike ourselves? Will a subsequent stage of moral development see us reconceiving existential risk in far less anthropocentric terms?

In The Precipice, I mostly focus on humanity — but not because all intrinsic value in the universe lies in the human species. Rather, I present humans as the only beings on Earth able to respond to moral argumentation and to reason, in order to determine what it is best to do for Earth and for all of its species. If we had never emerged, chimpanzees wouldn’t have taken on this role of reasoning out the best way to balance resources among the species, or to avoid suffering that happens on this planet. So humans play a unique role on Earth, which stems from our instrumental value.

When we now consider this longer future, we should note that for all of the internal strife in humanity today (all the differences among cultures and countries), we’ve never been more united. For most of our past, humans led highly localized lives, separated onto different continents, and with distinct regions completely out of contact with each other. Only quite recently have we come into such close and frequent contact and communication across the world. And this era itself might not last. Either through travelling to other planets, or through humanity evolving in different directions, we might become more fragmented again. So this may be a rare moment when we can make certain unified choices.

That doesn’t mean we should inevitably assume it best for humanity to be as unified as possible. It might be best to settle millions of worlds, set in motion in different ways, and let them decide what to do. But for right now, we can talk it through together. I think of humanity today as pluripotent. This current seed of humanity could develop in lots of different ways — from our current position where we can reason together about how we want to develop, and can choose very carefully.

We need to protect this seed. But as you suggested, we also need to flourish. We could flourish (and help other beings to flourish) in many different ways. In roughly one billion years, for example, due to our sun’s increasing brightness as it ages, the biosphere would die without some form of intervention. For now at least, only humans possess the potential to save this biosphere, either by protecting it for several additional billion years on Earth, or by taking it to other planets around other stars, and perhaps extending Earth’s biosphere in thousands of places over much longer timespans. So here again, I wouldn’t think of humanity as the sole value of the universe, but as a steward of that value.

Finally then, for one model of highly personalized evolution along the precipice, could you describe your own lived trajectory from a career in computer science, to one of academic philosophy, to more pointed engagement on questions of global health and poverty, to policy advising, to playing a significant role in the effective-altruism movement, and then to taking up existential risk (and, I’d say, existential potential)? What useful example might that trajectory offer to others “slow to turn to the future,” on the proactive role they too can play in safeguarding humanity’s further progress?

I’ve always wanted to help others as much as I can. I started off particularly concerned about people’s lives in poorer countries, with many lethal diseases no longer present in Australia as I grew up, or in the UK or US. I thought I’d focus mostly on these big-picture questions of global poverty and global health. And I saw how, through my own donations, I could do thousands of times as much good if I gave my money to effective organizations truly helping the people who need it most. This led to me making a pledge to give at least 10 percent of everything I earned to whichever groups and institutions could most effectively help others. Thousands of people joined with me in this pledge. I started a society called Giving What We Can. And we realized just how much good we could do for others, and the crucial importance of using reason and evidence to work out where to give that money, to make sure it had the most impact.

Through this same period, while talking with my Oxford colleague Nick Bostrom about existential risks, I started to sense these much more abstract concerns that also needed much more attention. And over time, I came to consider people of the future just as real as people of the present — and just as much in need of our assistance and protection. Right now, these people of the future can’t protect their own flourishing. They can’t protect themselves from 21st-century dangers and the harms that my own generation may impose upon them. They can’t protect themselves from existential risk, from never coming to be at all.

We need to take seriously their future flourishing. We need to inform ourselves about how great it could be. We need to start wider public conversations about how to protect it. We’ve become good at feeling compassion for individuals we can see on our TV screens, suffering from disasters. But we now need to develop a more expansive compassion for the people we can’t see — because they are not our present, but our future.