What kind of “opportunity for everyone” agenda might appeal just as much to rural Americans as to suburban and urban Americans? What common ground can these various communities find on questions of education, job-creation, healthcare, climate change, and public lands? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Senator Jon Tester. This present conversation focuses on Tester’s book Grounded: A Senator’s Lessons on Winning Back Rural America. Tester is a third-generation farmer and a US Senator representing Montana since 2006. A former elementary-school music teacher, Tester served on his local school board and then in the Montana Senate. Tester and his wife Sharla still operate the same farm near Big Sandy homesteaded by his grandparents more than a century ago, where they raise organic wheat, barley, safflower, lentils, millet, alfalfa hay, and peas. In the Senate, Tester serves on the Appropriations, Commerce, Indian Affairs, and Banking Committees — and as ranking member of the Veterans’ Affairs Committee.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Could you sketch how a New Deal legacy of thriving rural communities (with small-scale farms providing the nation a secure, resilient, nutritious food supply) helped bring you into the Democratic Party in the first place? And could you point to forms of corporate dominance now corroding that legacy?

JON TESTER: The New Deal showed us how all of America benefits from policies that empower family-farm agriculture. But that kind of agriculture needs fair competition in the marketplace, not some consolidated economy with people on a golf course determining what you’ll get for a bushel of wheat, or what a cow sells for. I mean actual market competition, capitalism that really works — where you get value for what you raise, and where people value what you raise.

Right now, for many Americans in production agriculture (especially the folks who grow corn and grain and soy), you almost can’t help getting caught up in a pretty artificial marketplace, with lots of consolidation, and also a lot of taxpayer dollars in the form of subsidies. So a number of different policies come to mind to support small-scale farms. Country-of-origin labeling would help. Enforcing the Packers and Stockyards Act would help. If we could limit subsidies only to where they’re really needed, I think farmers would embrace that. They would actually prefer that. They want their income coming from the marketplace. They don’t want to get a federal-government check.

Market competition also needs to increase not just for products we sell, but for the products we buy. At the moment, whether you buy or sell farm chemicals or fertilizer (which I don’t do, because I’m organic, but this food system’s of course much bigger than me), whether you buy or sell wheat, corn, pork, chickens, beef, you face an overly consolidated marketplace, which basically never helps small-scale farms. That’s not why my grandparents got into this business. They wanted to do honest work, make an honest living, and responsibly support their family. Politicians who claim to cherish and respect America’s family farms should keep those virtues in mind, and design policies that help American families fulfill those dreams.

Cultural wedge issues (say on gun control, immigration, abortion) often leave Democrats today reluctant to even try competing in rural districts. But with Democrats currently “getting whupped in the messaging war,” what could an “opportunity for everyone” agenda look like? In what ways, for example, might its focus on “jobs, health care, fiscal responsibility, public education, energy…the environment, and public lands” resonate just as much among rural voters as among suburban and urban voters?

Rural America has depopulated in a big, big way over the past 50 or 60 years. But that also makes for a lot of opportunity. An opportunity agenda for people in agriculture might start by helping them to vertically integrate, to participate in farmers’ markets and sell directly and really get to know their consumers — all of which we’d lost for a few decades. All of that helps these producers to create new markets for themselves, and to create more jobs. And by the way, this doesn’t mean you need a bunch of one-size-fits-all federal regulations, basically written by big agribusiness companies seeking to stifle growth for rural America’s small producers and processors. You can have both effective industry regulation and flexible regulations to fit a local community’s needs. We did it with the 2011 Food Safety Modernization Act. We can do it today. First you need to make sure that folks in rural America believe the federal government has their back (just like FDR had farmers’ backs in the 30s). Then you can move forward to help grow our rural communities, without people worried that you’re trying to deplete them.

As far as wedge issues go, I’d actually start with the amount of money in American political campaigns and all that, as really the root of evil. Though I’d also say that Montanans are very, very concerned about the incidence of gun deaths out there in rural America. And Montanans understand that not everybody has the same set of challenges when it comes to specific economic factors and to poverty, but that we all need to make our communities whole, in whatever ways we can. So some people don’t want the camel’s nose out of the tent on anything having to do with guns or choice or any of that — on both sides. But you have to listen when you can. You have to be honest about where you stand, and try to find some middle ground. Democrats have plenty of opportunity all over the place, especially right now, when it comes to finding that middle ground.

As a resident of a rural community “built… for the most part… by compromise and cooperation,” as a Senator from a state that voted for Donald Trump by a 20-point margin in 2016, you committed to working with this new President when you could, and holding him accountable when you must. For example, instead of rolling your eyes at Trump’s wishful identifications with the military, you quickly helped pass a number of bills improving conditions for US veterans. What could all Democrats and all Congressmembers learn from this approach, honed in the Montana Legislature, of taking “a win when we can get a win”?

You got it exactly right. We can’t just oppose a bill because somebody from the other side proposed it. If it’s good for America, then we ought to work hard to pass it. In my particular case, as ranking member on the Veterans’ Affairs Committee, and having worked on that committee since I came to the Senate in 2007, I’ve had to familiarize myself as much as possible with all the issues. I’ve worked to get good legislation passed by any Republican or Democrat, as long as it moved the ball forward for our nation’s veterans. When I graduated from high school, the Vietnam War had pretty much just ended. And I remember distinctly how our Vietnam veterans got treated when they came back home. They’d done their job, and fought like hell, and served our country with distinction throughout a very unpopular war. They deserved the best from us in return, and they didn’t get that.

In the book I mention one Vietnam veteran standing up and pointing his finger at me, and saying: “You’re not going to treat this group of veterans the way we got treated.” That man still sticks with me 13 years later. Serving this veteran and all the other veterans I’ve met across Montana has nothing to do with who our current President is, or which side supports which policies. I picture that man pointing his finger at me, and I know I need to do my best for all of our veterans, period. And like you said, we’ve passed a bunch of bills since 2016. The President signed them, and I applauded his actions on that. I worked hard on those bills, and appreciated his support.

Grounded mentions that your Montana staff spends a significant amount of time simply making sure “our state’s veterans navigate the mess of the VA in order to get… the benefits they’ve earned.” Could you say more about why all Americans should share your sense of outrage with US political leaders often willingly rushing to war, yet then failing so drastically to care for the men and women whose whole lives get reshaped by these military campaigns?

All I ask from leaders in Washington, D.C. is to keep the promises we’ve made to our veterans. We’ve made fundamental promises on healthcare. We’ve pledged that if you go to war, and you come back changed (whether that injury is seen or unseen), we’ll do everything we can to make you whole again. And by the way, that commitment doesn’t diminish over time. For all of those folks who served in Vietnam and got exposed to Agent Orange (this incredibly powerful toxin, causing all sorts of cancers and conditions like Parkinson’s), we’ll continue fighting like hell to get your treatments covered. We won’t consider this a situation where we should make a point by saving some money.

When we decide to put our folks in danger, when we send them to war, you rarely hear about budget concerns. We act to defend our political freedom. We do it for the flag, for America. And we need that same sense of commitment when it comes to taking care of veterans. These folks fought hard for our way of life. They fought to make America the greatest country in the world. They fought to make sure that I have freedom of religion, freedom of speech, an ability to assemble and protest against the government if I so choose. But here in Congress, folks sometimes seem to get amnesia, and forget about all the sacrifices these guys and gals have made for us. So we in Congress need to step up. We need to show our enduring thanks.

Keep in mind that we have an all-volunteer military. If we expect this all-volunteer military to be staffed with quality soldiers, then we need to recognize that our young people watch how we treat our veterans today. We should live up to our promises in any case. But it’s also just in our own best interests to do so.

Again in terms of promises, here the “broken promises for countless Americans who live in sovereign nations across rural America,” could you speak (from a policy perspective honed through Senate service on the Indian Affairs Committee) to how the primary concerns for our diverse range of indigenous communities (“quality health care, nutrition, cultural preservation, community safety, education…strong economies”) all revolve “around the linchpin of independent self-governance and effective government-to-government communication between tribal nations and the feds”?

Well, a lot of folks who serve in the Senate don’t have much experience with Indian tribes, because they don’t have reservations in their state, or the tribes might only make up a very small part of the population. A lot of political leaders haven’t educated themselves on the federal government’s legal trust responsibilities that we have for our Native American communities. Those commitments really require a different approach to governance. This starts, quite frankly, with self-determination. That means Native American tribes controlling their own future and maintaining their sovereignty. That means the federal government treating these tribes more like it treats state governments than like a group of people in a neighborhood. We need direct communication and a deep understanding between the federal government and the tribes, between state governments and tribes, between county governments and tribes, to address the challenges within Indian country.

So when the federal government considers allowing a pipeline built through Fort Peck, which is happening right now with the XL pipeline, we absolutely need the company proposing that pipeline, and the agencies reviewing that pipeline, to consult directly with impacted tribes. The federal government especially needs to listen to the tribes. We need to listen with two ears and one mouth — and work hard to accommodate their needs. Besides state and county governments, no other political entity I know has the kinds of rights given through trust responsibilities that Native Americans have. Federal officials need to understand this, and understand it well. For now, too many of us end up failing to honor the spirit of these commitments that our federal government has made into perpetuity.

Rural communities likewise can sense the climate changing “under our hands and in our bones…. The plants are telling us…. The bugs are showing us…. Something is terribly wrong with the Earth…. and we’re foolish to ignore it as it quietly creeps under the floorboards.” So again, what kinds of conversations might best help to unite here rural residents (confronting erratic growing seasons, unpredictable and volatile agricultural markets, spiking crop-insurance costs, restrictions on personal recreation, and harms to tourist industries) with urban climate activists — so that each side comes to see the other as part of a collaborative solution, rather than as a potential problem or rival or enemy?

When I first got here, Joe Lieberman and John McCain were working on a climate solution which could bring people together. That might have been a bit ahead of its time back then. But almost 15 years later, climate change feels much more present in people’s lives. You really have to bury your head in the sand, especially if you work in agriculture, to act like you don’t see climate change all around you. If not for the grace of god, you yourself might have the field flooded or droughted out or blown out or whatever tomorrow. So what will it take to connect those folks you mentioned? The same solid work it takes to get people in the wood- and paper-products industries talking with the conservationists. Really for each controversial issue out there, we need these same efforts of bringing everybody to the table, and getting them talking to one another.

With this current COVID bill, Mitch McConnell just threw it on the table and said: “Here’s the bill.” No committee process. No conversation. No visit with one another. Nothing like bipartisanship. Thomas Jefferson and Mike Mansfield must have rolled over in their graves. I mean, when you get people working across the aisle to put together a bill, then they start understanding what it’s like to walk in each other’s shoes. They figure out how to find common ground and move forward with common-sense solutions to our shared problems. You almost can’t help getting a better bill that way, with input from both sides. But right now we’ve got a big problem, Mission Control, and if we don’t talk to one another and cooperate to get our climate in better shape, our kids will pay the horrible price — since I don’t see them moving to some other planet.

Here can we also go back to certain dangers you see in applying a one-size-fits-all approach to federal policy? Where, for example, do conservative pushes for privatizing education reveal an indifference to how such an agenda harms rural communities? Where has Democrat-driven financial regulation undermined local banks and credit unions (and by extension, whole communities)? And how do dominant corporations pursue their own goals by embracing regulatory mechanisms that leave small-scale rural businesses ever more vulnerable?

Not to beat a dead horse, but I think this also starts with better communication, and with listening more than you talk. Politicians (and to be honest, many of their fellow Americans) have gotten really good at telling people what to think — when we all should try harder to hear out what others have to say, so we can move forward in ways that make sense for everybody. And look, it does take a lot more work to try to understand how a policy affects all different kinds of places (whether rural versus urban, poor versus rich, highly industrialized or not at all). But for me that again just boils down to getting my best ideas from people on the ground, from people dealing with certain problems every single day.

Listening to whoever has the best ideas doesn’t always mean listening to your own side. It also doesn’t mean laying down one big old tarp across the whole country and saying: “Here’s the plan. Now live with it. If it doesn’t fit perfectly, too bad.” Instead we always have to do the tough work of negotiating and finding common ground, and factoring in all the different struggles out there in different populations.

To make this focus on common ground quite literal for a minute, your book calls for revitalized commitments to forever improving our management of public lands, for the generations immediately to follow. Could we contrast that perspective to insidious corporate efforts to transfer federal lands first to cash-strapped states, and then to private ownership? Could we throw in President Trump’s cartoon-level crass opportunism in his appeals to eminent domain? And could you talk about Democrats here having potential claim to “conservative” values at least as much as any present-day Republican?

Absolutely. I really see Democrats having a leg up on public lands. As one person in my town told me: “I’m not a millionaire, but I can hunt on some of America’s best hunting grounds, and fish some of the best blue-ribbon trout streams in this country. I didn’t have to buy these lands and those rights myself, because I’m already a public landowner.” We all need to see it as our fortunate responsibility to manage these lands. For Americans here right now, we need to make sure they have access to good habitat. And for Americans to come, we better make sure not to squander what our parents left for us.

“Conservation” and “conservative” might sound a lot alike, okay? But Democrats have an edge here, and should use that to help rural people, especially rural folks who hunt and fish and hike and camp. They genuinely appreciate all of that. They understand the need for good management, and can respect a federal government that does this right. Teddy Roosevelt, a Republican, had such an incredible vision over a hundred years ago, when it came to founding our national-park system. Now it’s our job to protect that vision and maintain these pristine, beautiful ecosystems for our kids and grandkids. That’s all kind of a slam dunk for Democrats, but also just the right thing to do.

Along these lines of preserving America’s foundational character, what makes “runaway, unaccountable campaign spending” the most urgent issue facing America’s political future?

So Montana has been there and done that. We had Copper Kings trying to buy Senate and Governor races a hundred years ago. That led to a public vote which stopped corporations from just spending their way to victory, by putting some safeguards on our campaigns. Montanans had the bottom line that this kind of spending hurts democracy. It hurts Democrats. It hurts Republicans. It hurts independents, and libertarians. But most importantly, it hurts our whole democratic system — the best form of government the world has ever seen. So we need to fix that. We can’t have people buy their way to our statehouses and to Washington.

I think a lot of Americans voted for Donald Trump, by the way, because they see Washington as just totally corrupt. A big part of this has to do with the outrageous amount of money that gets spent on election campaigns. And what constantly amazes me, Andy, is all the politicians standing up and saying: “Oh yeah, I want campaign-finance reform.” Then they get here and don’t do one damn thing about it, other than maybe sometimes giving it more lip service. They don’t lead the charge. They don’t push the legislation that would get it done. They actually block that legislation. That really threatens our democracy’s long-term future, even if we can survive Donald Trump.

I found especially illuminating here Grounded’s account not just of irresponsible candidates getting elected, but of entire legislatures failing even to take up the most pressing policy challenges — for fear of unleashing relentless primary counterattack. What kind of first-person experience can you offer on watching this dynamic transform the US Senate into “a shell of what it once was”?

That whole thing causes just incredible paralysis for Senators always looking over their right or left shoulders. If you go back maybe 10 years, Byron Dorgan said: “If the Interstate Highways Act came before the Senate today, no way could we pass it.” Somebody would start running commercials about your nonstop taxing-and-spending or whatever. But we didn’t become the world leader by skipping out on investments in education, infrastructure — and family-farm agriculture, by the way.

The Senate really, really needs people who aren’t single-issue politicians, who don’t just show up with some ax to grind, who commit (as we all pledge) to looking out for the whole country’s best interests. Though with all the money dumped into campaigns today, some Senators do show up not just bought and paid for — but terrified of their own financial backers. Or else they might start from a perspective so far, far, far to the right, or so far, far, far to the left, that we really can’t get much done together.

Specifically in terms of government spending, how would you call on fellow Democrats, particularly in contrast to a personally corrupt, administratively negligent, inequality-reinforcing Trump administration (and its Republican Party-wide enablers), to reclaim the values of fiscal responsibility and accountability — from the level of individual citizens having “some skin in the game,” all the way up to long-term national prosperity?

I had the good fortune of getting out on the combine last weekend, harvesting peas and winter wheat. Getting out on a piece of equipment like that, and listening to the motor humming, gives you a good chance to think. And when I thought about the post-World War Two rebuilding era, I thought about times with empowered working families, with workers making a livable wage, receiving solid benefits, operating in safe conditions. Today people have to work multiple jobs just to survive in many cases. That diminishes our whole way of life. Then when you go to these families and say “Geez, we need more taxes for infrastructure and education,” of course they at first respond: “My god, I already have two jobs, just trying to make ends meet. I can’t afford more taxes right now.” So we first need to make our tax code, frankly, much more fair across the board. We had the balance right at one time, but we ripped up that code because certain folks didn’t like, for example, its progressive income-tax rates.

So what should we do today to ensure real fiscal responsibility — now that we have 27 trillion dollars in debt? Well, we didn’t get into this problem overnight. We’ll need a sustained effort to get out of it. But we can do that, if we act like you would on a farm. That would start with taking a hard look at all the carve-outs in this current tax code, and seeing where we’re just throwing away money. Then we have to take a hard look at everything we’re paying for, and ask ourselves as Senators (regardless of which party): “Which of this spending do we really need? Which helps us to move forward together, and which just sets us up for future problems?” Then we have to put the necessary money into programs that really help drive the prosperity of families and the overall economy (including businesses, by the way). And then we also need to start setting aside some money to pay off our debt.

One real travesty of this Trump administration comes from the fact that when we had a humming economy, we still ran up a trillion dollars each year in debt. Anybody in business, anybody in agriculture, any family farmer will tell you that during the good times, you pay down debt. You don’t add to the debt, unless you want a real disaster (because during the bad times, you definitely might need to accrue some debt). Personally, I don’t think we should try to run this government like a business. But some of those basic values, some of those basic principles that help small businesses and family farms to thrive, do fit well for running government. If you don’t need it, don’t buy it. But if it helps move the economy forward, then go ahead and utilize those dollars.

Now to take up one of those divisive cultural issues mentioned earlier, Grounded describes movingly the decades you’ve spent: “making a living with firearms…swiftly and carefully dispatching cows and hogs, each with a well-aimed single shot, before skinning them in my yard and butchering them in my shop.” This book also pauses on the one time a meeting in your Senate office left you sobbing — after talking to parents of Sandy Hook victims. As somebody who, at age five or six, had his dad place a rifle in his hands, and a commitment “to respect the life around you” lodged in his being, how might you make concrete your claims that “Everything the NRA does now is designed to raise money by… tapping into a deep root of distrust and fear,” and that “the biggest threat to legal gun ownership is the NRA’s stubborn zero-tolerance policy for common sense”?

From time in my high school’s hunter-safety organization, all the way to the present, I’ve watched the NRA change into this big-money organization. I see them today constantly saying unbelievable things just to raise more money. The NRA no longer defends gun rights, in my opinion. It actually threatens them. At one point in their history, I truly admired this organization. But how can you anymore, when they just put everything off limits? They don’t care about gun safety today. I’m not even sure who in this organization’s current leadership knows which end of the gun the bullet comes out of. Instead of talking about respect, and gun safety, and how we need to use these tools with extreme care, because after you pull that trigger you can’t pull that bullet back — instead they just say: “No, no, no, no, no.”

But a big majority of people in rural America understand the importance of gun safety. I mean, this book could have been written about me or about any of my neighbors. And my neighbors will tell you that when they heard about Sandy Hook, it just turned their stomach. Even for an absolute Second Amendment defender like me or my neighbors, that doesn’t mean you have no common sense associated with the Second Amendment. But the NRA’s response in that moment showed no common sense whatsoever. It showed that an organization only concerned with raising money has no real interest in common sense. And this all just means that the pendulum will swing back hard someday. A lot of Americans finally will say: “You know what? The NRA has fed us this baloney for decades now. The hell with it. No guns.” And you’ll see me standing there going: “Come on, man. I actually utilize guns for protection, for vermin control, for butchering beef, for enjoyment when I can go out target shooting.” But it will just get too hard to find common ground, because the NRA will have taken all common sense out of the discussion.

Again in terms of complex cultural concerns, here a “deep, gnarly root of racism in rural America,” I also found quite moving your account of how past forms of fellowship “among men who look like me, talk like me, live in rural America like me, and did much of the same work I do…seem…oddly outdated now that I’m a Senator.” Given our divisive debates today about who gets to consider themselves a “real American,” about who should see themselves as an incorrigible oppressor, how could all sides do better by recognizing that each of us deserves the sense of belonging that such fraternal associations once provided you — but that we also can’t let our needs for belonging lead us to excluding or neglecting or projecting one-dimensional stereotypes onto our fellow Americans?

Unless you’re Native American, Andy, your family immigrated to this country at some point along the way. So this debate on immigration always interests me. But to be honest with you, I actually don’t think a lot of our racism comes out of people having evil intent. A lot of times, somebody just doesn’t understand the challenges other people face, and can’t put themselves in somebody else’s shoes. In some cases, of course evil intent does exist. But look, I live in a 99-percent white community in Big Sandy. We all could do a better job of exposing ourselves to different perspectives and cultures.

If you get raised out here where I’m at, unless you decide to jump on an airplane, you just don’t meet a lot of folks from different backgrounds and experiences. But I do think we all need a better understanding of the challenges our fellow Americans face — an understanding that comes not just from what talking heads tell you, but from really interacting with people.

Along similar lines, you describe your 2018 Senate reelection as confirming character and authenticity’s enduring importance in rural America. What lessons would you hope for many fellow rural Americans to take from their 2016 presidential vote now looking like one of the worst character judgments in US history? And how would you hope for Democrats, moderates, technocrats to absorb their own lesson here that when large groups of Americans don’t feel adequately represented, don’t feel listened to or supported by political leaders: “A phony will come along and fake his way through it, and he will win hearts and threaten our democracy in the process”?

Here’s what I hope has transpired over the past four years. Hopefully, when many Americans now think back to Donald Trump ranting about how he’d make America great again (as if America had ever lost its greatness), they can see, instead, that President Trump has destroyed relationships with our long-term allies. President Trump has destroyed our economy. President Trump has increased our national debt by 4 or 5 trillion dollars. President Trump has diminished government checks and balances that help preserve American freedom. Does all of that add up to making America great again?

So I absolutely agree with that point about how a phony can come along and endanger our democracy when a lot of people don’t feel listened to, and don’t see their personal concerns addressed. But I hope that, when Americans now look back, they can see Donald Trump as the snake-oil salesman he’s been all along. I’ve watched this man up close. He doesn’t understand rural America, for sure. He doesn’t seem to understand democracy. He certainly doesn’t grasp what our forefathers had in mind for American self-governance. And I know many people still might say to all that: “Well good, we needed somebody to blow up the place.” Yes, President Trump has done some damage, no doubt. But has that damage helped you or hurt you?

My book has that story about my dad buying a Cadillac. He couldn’t even get it in the garage [Laughter]. And a neighbor, who had come to get his meat cut, said something to the effect of: “Dave, if you can afford a car like this, you probably don’t need my business.” So Dad took the car back. I think we have an opportunity for that kind of self-reflection this year. When folks go to the polls this November (or however they vote), I hope they ask themselves: “Did I really get what I paid for?” If not, then I think it’s time to return the Cadillac.

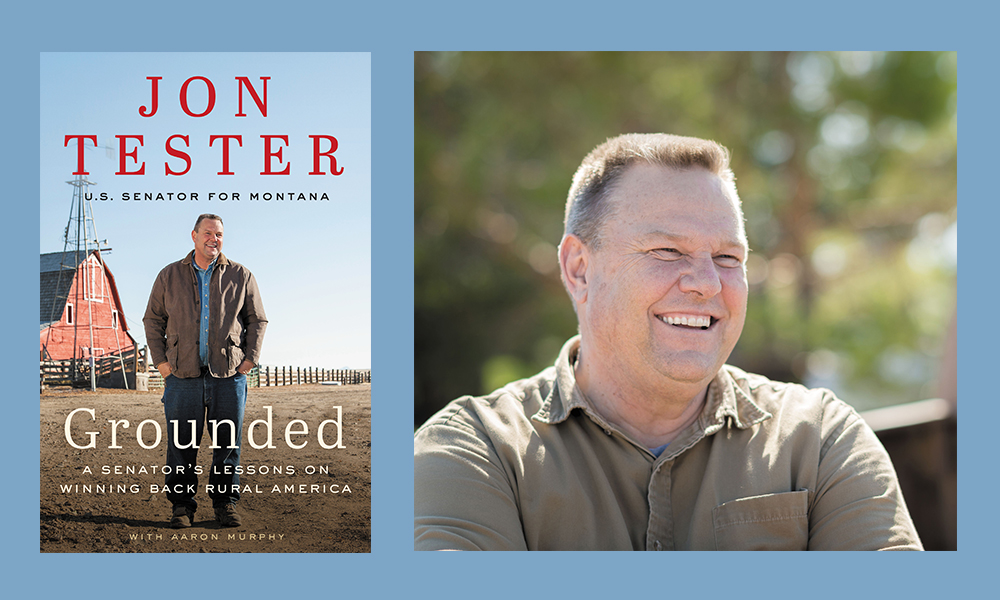

Portrait of Senator Tester by Tony Bynum.