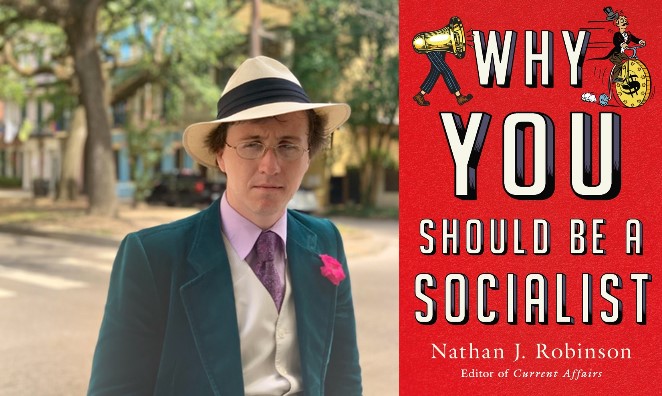

How might socialists prioritize personal freedom? How might they reimagine ordinary working life beyond both Amazon warehouses and familiar communist models? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Nathan J. Robinson. This present conversation focuses on Robinson’s book Why You Should Be a Socialist. Robinson edits Current Affairs, a print magazine of political and cultural analysis. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Guardian, The New Republic, The Nation, and elsewhere. A graduate of Yale Law School, he is a PhD student in Sociology and Social Policy at Harvard, where his work focuses on the US criminal-justice system.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Could we start with libertarian socialism — the type of socialism most resented, you say, by capitalists and communists alike? Could you outline a socialism that begins from the goal of securing and expanding freedom? Could you describe putting shared resources towards this basic aim of ensuring everyday people have control over their own lives?

NATHAN J. ROBINSON: I’m so glad you started there. Most people start with “What is socialism?” [Laughter], the most frustrating question. Socialism, as a very rich political tradition, of course has a long history of intra-socialist arguments. I personally came to socialism through a college class called “Marxism versus Anarchism.” It fascinated me to encounter this big debate between people who had a shared emphasis on egalitarianism, but who were debating what egalitarianism means and what freedom means. My sympathies instantly went to the libertarian socialists — in the discussions between Marx and Proudhon, and between Marx and Bakunin. Proudhon said to Marx at one point: “let us not pose as the apostles of a new religion,” and let us not “dream of indoctrinating the people.” Bakunin argued that if you’re not careful, if you don’t value freedom alongside equality, you’ll end up more or less with a priestly intellectual caste, who will try to rule over people.

One of my big influences, Noam Chomsky, of course has said much the same thing, and has identified himself with the anarchist socialist tradition. And from that tradition’s perspective, when people say “The central lesson of 20th-century socialism is that the capitalists were right,” I’d instead say that, actually, the lesson is the libertarian socialists were right — because they critiqued something that called itself socialism, but that never became authentically democratic, and that failed to prioritize civil liberties, and never took great care to ensure that a small class of people did not rule over everybody else. Bakunin said people were still going to be beaten with a stick, but that now we’d call it the people’s stick [Laughter]. But what’s important is that even when this does happen, it certainly doesn’t discredit socialism as a whole, because people like Emma Goldman and Bertrand Russell have always said we need a socialism that prioritizes freedom.

Now, when we ask “What does freedom really look like?” that’s a big question. I discuss it a lot in this book. But we have clear examples of what freedom does not look like. It doesn’t look like an oppressive authoritarian state, but nor does it look like oppressive employers controlling their workers’ lives and exploiting them. So it doesn’t look like a typical communist country, but it also doesn’t look an Amazon warehouse. And today’s socialists face the task of being radically inventive, as they envision something that looks like neither of those.

Still in terms of what socialism freedom might in fact look like, here perhaps slightly less in an Emma Goldman vein than an Oscar Wilde vein, could you clarify why socialism must be (and how it can be) friendly, palatable, fun? Why should socialism always strive “not just to create better living standards but to create collective joy” — to construct a utopian space more like New Orleans’s Mardi Gras than like Berlin’s Karl-Marx-Allee? And how might this pleasure-pursuing mode of socialism face up to your book’s incisive question: “Are you a hypocrite if you profess socialist values but do not live as an ascetic?”

First because of the roses that come along with the bread, right? Socialists have long united around this powerful expression of bread and roses. The Democratic Socialists of America take a rose as their symbol. Their logo is not a hunk of bread. So we have to take the roses seriously [Laughter]. We can’t accept some bland utilitarian life in which we are just bodies being kept alive and having our physical needs met. We all deserve the good life, and the good life doesn’t just consist of a full belly. So when we say things like “Housing for all,” we don’t mean sticking people in some dreary tower block. We mean beautiful housing for all, because we recognize pleasure as an important part of life. We mean embracing this incredible Earth we’ve been given, which has so many delights and so many possibilities — and we mean realizing those possibilities.

So I do consider Oscar Wilde’s essay “The Soul of Man under Socialism” quite fascinating. I disagree with a lot of it, but I appreciate his primary point that socialism means individualism — which sounds paradoxical to those who think of individualism as maximizing your own economic power. Wilde instead talks about cultivating people’s creative and artistic spirits, and allowing each individual person to meet their potential and pursue their own distinct ends. Now, what does that have to do with socialism? Well, we recently published an interesting Current Affairs essay called “Capitalism Is Collectivist.” This essay makes the point that nothing destroys individualism more than working in an Amazon warehouse, or operating as a disposable part of some production machine, or working in a Walmart. In each of those cases, the individual actually gets sacrificed for the collective good of the institution and its planners.

How then do we find out what each individual person wants from life? How do we give them, to the degree possible, all of those things? This book often describes utopias. It basically says: “Let’s think about what each of our fulfilled lives would look like.” I mean, I have asked many people to imagine what they would need for true fulfillment. Fulfillment does not just mean guaranteeing some depressingly sparse standard of living. It means fulfilling human potential (and not in some abstract, meaningless sense of that phrase). It means: let’s actually look around the world and find the examples where people become their true selves or their best selves. The book mentions Mardi Gras because I live in New Orleans, and to me Mardi Gras remains this amazing phenomenon with no profit motive. No corporations advertise on Mardi Gras floats. People spend the whole year making their costumes for the sheer pleasure of wearing them. Mardi Gras happens because it is joyful. It has this interesting mixture of a communal spirit (with everybody doing something together, getting to know one another, acting friendly, and connecting for reasons that have nothing to do with maximizing economic interests), and of individualism (because everyone wears different costumes expressing their true nature). I love that spirit. I often ask myself: How do we make that spirit more than just one event happening in one city once a year?

With that spirit still in mind, and to start exploring some of the useful, ever-provisional distinctions this book provides, could you first situate your own socialist approach alongside pragmatic efforts to improve people’s lives in a particular here and now, and then alongside a more “defiantly unrealistic… ambitious in the extreme” vision skeptical of pragmatism’s self-imposed horizons? And would it make sense here to distinguish a bit between a social-democratic perspective that points to contemporary Scandinavian societies’ realization of relatively equalizing economic arrangements, and a future-oriented democratic-socialist perspective forever pushing for further elimination of exploitation and hierarchy?

Yeah, the reason I don’t want to give fixed answers for those kinds of definitional questions is that they inevitably leave some readers dissatisfied, since these terms get used differently by different people. For example, Jacobin calls Bernie Sanders a class-struggle social democrat, which they consider a particular kind of social democrat. Other people call Bernie a democratic socialist. Other people say: “Oh no, he’s not socialist at all.” So I only can give my own somewhat personal take on what these terms allow us to clear up, and what they obscure.

For me, the word “socialist” describes a radical political tradition. Words like “progressive” and even “left” have become kind of watered-down. People to the left of Bernie might call themselves progressive, Bernie calls himself a progressive, and Obama would call himself a progressive. Everyone’s a progressive. “Progress” is good by definition — it’s empty. But today especially, we need to distinguish between someone like Obama and someone like Bernie. “Socialist” kind of plants its flag in the ground, and says: “I’m placing myself explicitly in a tradition with specific aspirations.” Socialists have in common the desire for a radical change in who owns and controls property. They believe in worker ownership or public ownership. Some come across as more skeptical of the state. Some claim that we can turn the state towards good purposes. Still when you call yourself a socialist, this suggests redistribution of ownership and of control.

I like the term for that reason. I like the utopian or radical elements. As I’ve mentioned, I came to socialist thinking through my encounter with the anarchists. And I love the anarchist slogan: “Demand the impossible.” Again, this could sound self-contradictory and obviously stupid. But as I’ve grown up and begun to look at the world, I can’t help recognizing that we have no idea what is or isn’t possible. People confidently pronounce, but really don’t know. Think of all the voices in 2016 saying “It’s just impossible for Donald Trump to become president.” Then think of all that you do want, but that people call impossible.

Similarly, I appreciate that people in this socialist tradition have refused to accept what others declare the pragmatic thing to do, the thing you have to do. I find it very inspiring that socialists have dared to imagine beyond these supposed constraints on their movement. I want more people to question conventional wisdom around what can and cannot be done. So in terms of how a social democrat might differ from a democratic socialist, I guess I would see someone who embraces the label “social democrat” as not really sharing this inclination to look beyond, to ask: “Well, if I could glimpse one hundred years into my dream future, what would it look like?” A social democrat instead looks at the present world, notes a few things wrong with it, and tries to patch those up a bit, and to make life a little better. But again, all of these terms will mean different things to different people. Jacobin thinks of “social democrat” as a radical term. The German Social Democratic Party once was a socialist party. So I probably contradicted myself a couple of times in the book on this [Laughter].

Here could we pick up on related distinctions between “a socialist ethic…anger at capitalism over its systematic destructiveness and injustice…and a socialist economy that rearranges the way goods are produced and distributed”? What makes a socialist ethic “both more and less than a socialist economy?” Where might you place a socialist ethic on a continuum extending, say, from an expressive affirmation of socialist goals, to a concrete dismantling of the capitalist relations one deplores? Or where might a socialist ethic fit on a continuum stretching from abstracted enduring values, to specific prescriptions for present circumstances?

That great Terry Eagleton quote comes to mind, describing a socialist as “just someone who is unable to get over his or her astonishment that most people who have lived and died have spent lives of wretched, fruitless, unremitting toil.” So I’d begin from that kind of disgust with certain features of the world, certain things that happen to some of us, certain ways that workers get treated. If we can agree that people should meaningfully participate in the decisions that affect their lives, then we at least can assume that if you pulled workers quietly aside and asked “Do you like the fact that if you drop below packing some set number of boxes per hour, a robot will fire you?” they probably would say: “No, that’s not a process I personally would have established. Amazon has established that process in order to maximize output, and doesn’t care whether I get to have a job tomorrow.”

And of course many counter-arguments get put to you — rationalizing or explaining away these arrangements, or making it seem like people deserve the life they have. But the socialist doesn’t accept those arguments, can’t stop questioning them, can’t stop thinking: Other possibilities must exist. And the socialist ethic develops from this feeling of strong solidarity with people in trying conditions, and from looking around and seeing which side you’re on in such conflicts. Do you side with the masters of the universe? Or do you side with the people working for the masters of the universe? Socialists have a very strong consciousness on these questions.

But as your own question suggests, nothing I just said really describes an alternative way of arranging an economy. Instead it describes a feeling — a feeling of connection to your fellow human beings, a feeling of disgust at what they have to go through. So if you ask someone with a socialist ethic “Well, what would a socialist society really look like?” they might not have an answer. Many of them don’t. And because of that, somebody might accuse them of not understanding socialism or not understanding capitalism. But people with this ethic understand quite well the basic philosophy of socialism. Historically, socialists have taken up this feeling and said: “Let’s look at the sources of oppression. Let’s look at how exploitation functions. Let’s look at what makes people feel so alienated from their jobs. Let’s come up with ideas for how to eliminate all of that. And whatever comes out of this will show us socialism as a social structure, and as an economic structure.”

I do consider it very unfair for people to criticize socialists by saying “Okay, give me a blueprint for how this will work” — because human beings have no harder question to answer. How do you eliminate all human injustice? Well, through experimentation, clearly. And this doesn’t suggest some foundational flaw in socialist thinking. Even Leszek Kołakowski, very pessimistic after living as a dissident in a communist country, drew this same distinction about creating an alternative society. He said the setbacks don’t invalidate the socialist ethic. And it worried him to see capitalists saying: “See, only me pursuing my self-interest and you pursuing your self-interest will lead to justice and to the good.” The socialist ethic rejects that whole line of thinking, because it sees all the ways that people prey on each other and take advantage of each other.

So today socialists do face these very, very difficult questions of: “Well, how do we take this philosophy and translate it into real-world social change that gets us closer and closer to actualizing our ideals, to having our basic principles take on meaning?” That’s why we need socialist economists and socialist lawyers and socialist workers and socialist artists. That’s why people who share these convictions and aspirations need to pool together their collective knowledge in order to answer those most difficult of questions.

In terms of pooling together, your book also parses political mobilizing and political organizing. What clarifying contrast can you offer, say, between Barack Obama’s ultimate prioritization on political mobilizing for the 2008 and 2012 elections, and the most promising efforts you see at political organizing today?

Everyone should read Jane McAlevey’s book No Shortcuts, which points to this incredibly useful distinction long recognized by labor organizers, who might ask: “Are you basically taking all the people who agree with you right now and activating them, or are you looking outwards and trying to build your movement and get more people to join it?” Mobilizing here mainly just involves getting out your core activists to protest. Organizing means finding the people who partially disagree with you and turning them around. Unless you already have a majority, or you intend to seize power as a small vanguard party, you can’t do much unless you organize.

Historically, one tactical failure of liberal politics has come from not understanding this distinction. Of course I also see other problems with liberal aspirations. But even if we assume that Barack Obama and the leftists have some shared goals, big differences still exist on how you approach politics. When we on the left call for a mass movement, we don’t just mean that as rhetoric. We mean the real thing either exists or it doesn’t. You can fake it for a little while, but eventually you need numbers. You need active people.

I respect Bernie Sanders so much in part because he gets this distinction in ways most people in our politics do not. Bernie understands this need to find people who don’t otherwise participate in politics, and explain to them what you want to do, and persuade them to take part. You have to bring them in. You have to give them meaningful ways to engage. You have to encourage them to activate other people. And you maybe noticed that I didn’t title this book Why You Are a Socialist. I titled it Why You Should Be a Socialist. Now, I suspect that many of this book’s readers already will have a socialist ethic. But I did want to frame the book for people who don’t yet share that ethic.

Returning then to present-day electoral politics, you cite Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s victory over established Democratic incumbent Joe Crowley as evidence that “many primary voters were perfectly willing to get behind a socialist if they offered an alternative to the uninspiring, centrist politics that has made the Democrats so unappealing.” Beyond AOC’s New York City-based district, what could or what does 21st-century democratic socialism look like in the suburbs, in the country’s center, in economically displaced culturally conservative communities (both white and nonwhite), in primary elections and in general elections?

So you do have Nancy Pelosi asking: “Well, AOC can win in Queens, but what about the rest of the country?” Or Senator Tammy Duckworth said something like: “But socialism can’t win in the Midwest.” But I’d argue that we would first need an organized socialist movement before we could make self-assured predictions like that. You can’t dismiss the possibility until we’ve actually run the experiment. And in fact, we have some persuasive evidence offered by Bernie Sanders winning 2016 primaries in so many states. It actually turns out that Democratic voters in those states seem more to the left than Democrats in New York. Democrats in Oklahoma seem more willing to take a chance on a socialist than Democrats in Massachusetts.

Here I also think back to the DSA Convention this summer, which brought together all of these elected officials from around the country, with state legislators and city council-people and school-board or library officers. Ruth Buffalo, a Native woman now in the North Dakota state legislature, ran as a DSA candidate focused on the neglect of missing and murdered indigenous women, and unseated a Republican who’d sponsored the state voter-ID law that threatened to disenfranchise Native Americans. Or I’ve spoken to people like Mik Pappas, a Pennsylvania housing-court judge working to reduce eviction rates, or khalid kamau on the South Fulton, Georgia city council, who describes the efforts of community land trusts to improve housing conditions.

US socialism already includes very different people in very different places. We have people of all races, all genders, in all kinds of states, getting elected to office explicitly as socialists — again with “socialism” meaning different things for different officials in different districts, but with everybody united by a disgust with exploitation and inequality and hierarchy, and a determination to provide some real alternatives.

In terms of this diversity among socialist points of view, your lucid account of young people’s political perspective shaped by debt, expensive healthcare, the prohibitive-seeming costs of raising children (all amid an economy offering relatively few satisfying and sustaining career prospects) stood out most to me. What might a mid-forties reader like myself still not grasp about how everyday lived experiences have shaped your own democratic-socialist vision?

Thanks for bringing this up. The book’s introduction offers that bit of an autobiographical element, where I describe watching people who went to college and then moved back in with their families, and sometimes dropped out. Or even when this doesn’t happen, most of my friends have giant piles of debt. Very few of them see it as realistic that they could own a house, unless they have parents who can provide the down payment. That idea of home ownership, or the idea of raising children, just sounds crazy. Who can afford that?

So then when many of us feel hopeless, and we hear this Steven Pinker story about how everything has gotten so much better, or this Cato Institute or American Enterprise Institute report trying to persuade us of how good we have it, that just doesn’t correspond to the facts of people’s everyday lives. They look at their bank account. They look at the lived reality of climate change. They feel desperately alone. They see the career they thought they could depend on disappear. They see social connections erode. They sense their company doesn’t give a shit whether they live or die (and they’re not wrong). And so you can’t just tell them: “Well actually, you should be happy to be so lucky — you have an iPhone and you didn’t die in a famine.” Because they’re not happy. They’re profoundly uncomfortable, for good reason. Living with a horrendous amount of unrepayable debt can sink you further and further into this psychologically debilitating experience. When you struggle to make your monthly housing payment, and you do not know what you would do if you got sick or had a car accident, if feels like your life can’t go anywhere. And of course I’m only describing the despair in this one wealthy country, let alone around the world.

As a millennial though, I also find it fascinating to see people younger than me already getting so politically active. You see so many informed, radical, angry teens looking at the facts on climate change, recognizing this massive problem bequeathed by the boomer generation, pissed off by this vivid sense of intergenerational injustice — with one group enriching itself and providing comfort for itself and not caring what that means for humanity’s future.

I just watched this Jeff Bezos lecture about the future of humanity, where he basically says: “Our growth is unsustainable. We’ll have to flee this planet. We need to go into space.” But you know that means Jeff Bezos going into space [Laughter], and the rest of us going to work in his warehouse. That’s probably why you don’t see older people getting on the Bernie train the way you see young people doing so. That divide really stood out in 2016. And it comes from this sense that somebody has stolen your future, this thought that something much better has to be possible, and this determination to make better things actually happen.

Well when I hint at something like a generational divide between us, I’m especially thinking about market concentration, particularly labor-market concentration, and what life opportunities looked like (at least for people of relative privilege) 15 years ago, versus what they look like today. So how might we take your incisive formulation that “Ironically, the concentration of capital means that one of the great fears about socialism…that decisions about what to sell would be made by small, unelected groups of bureaucrats, rather than determined by competition…is increasingly coming true under capitalism,” and apply it not just to consumer markets (“what to sell”), but to employment markets (what kinds of work one can do, under what conditions)?

Of course right now we have President Trump citing these low unemployment statistics. But socialists always have asked: “Which kinds of employment? Doing what? For how long? Under what conditions? With how much say over what you do?” There are lots of jobs but they are shit jobs that steal your waking hours and pay you as little as they can. I mean, I talk so much about Amazon warehouses just because I see those conditions spreading across society, stretching their tentacles as far as possible. And your question interests me in part because I don’t oppose concentration in every context. In many ways, socialists have pro-concentration sympathies. If we nationalized and sort of democratized Amazon’s internal structure, I’d have far less of a problem with this one huge entity. State-owned enterprises often have that kind of concentration.

But when these institutions don’t run democratically, then we have problems. So I personally would focus less on how many institutions we have, on “breaking up” big enterprises, and more on what you said about how many different kinds of opportunities workers can see, under what kinds of conditions, bringing along what sense of decency, accomplishing what meaningful work, and with what types of security so that you can hold employers accountable without fear of retaliation. If we only had three “companies” to work for, and if they all operated democratically, I wouldn’t necessarily think of that as a violation of socialist principles. Of course in the real world, as a practical matter, I think you’ve described accurately this problem of certain specific companies seizing so much control.

Yeah, we had started with a focus on collective joy, but I do also want to bring in this book’s less cheerful sides. So here could you first articulate your case for why leftists need to talk more about what they love (since “what we feel most deeply is warmth and tenderness”), and then for why leftists should forever sharpen, harness, voice their palpable sense of what they hate?

Right. I’m not quite talking about love in the sense of Marianne Williamson’s A Politics of Love book, though I would say that many socialists have a large range of emotional extremes, with deep love for certain things, as well as deep hate for other things. So in that passage where I discuss love, I also describe what makes us so angry much of the time — this senseless loss of all that humanity could create and could experience. I mention Jeremiah Moss’s blog and his excellent book Vanishing New York. Jeremiah always sounds really angry about wonderful old New York places shutting down. But Jeremiah’s anger comes out of this real, real love for the city. He resents and despises developers with no understanding of what these romantic and special and wonderful places mean to people who live in them and who regularly visit them.

I believe in that kind of anger. I recently wrote an essay titled “In Defense of Hatred,” because while you don’t have to hate people, you do have to hate injustice. You have to feel strong emotion when you see horrible things happen. Actually last night I had this moment, biking home through the French Quarter, when I burst into tears seeing homeless people sleeping in a lot of doorways, underneath these two-million-dollar houses. I see that every night and usually I don’t cry. But what really put me over the edge last night was that there was trash out to be picked up, and at a distance you literally couldn’t tell the difference between people in sleeping bags, and covered with stuff, from the piles of garbage. I saw bags of garbage and bags of people — people just reduced to the status of waste. Nobody coming along and offering them a soft bed. Colossal wealth everywhere and human beings forced to lie in a heap on the corner like refuse. I couldn’t contain my fury. I just wept and wept.

I had that basic thought of: How can we not be angry all the time? Many socialists feel this way. You actually can find a lot of truth in that bumper-sticker phrase: “If you’re not outraged, you’re not paying attention.” I saw these people sleeping right next to my own house. How can you ever stop thinking about that, if you have a functioning moral compass? And so a lot of socialist work today involves that kind of waking up, and trying to wake others up to obviously unacceptable situations happening all around them, and encouraging people to really think about both what they treasure and what we cannot accept.

Along those lines, I personally find your book’s critique most effective when you describe conservatives not as evil but as insufficiently ambitious, as taking for granted Margaret Thatcher’s capitalism-by-default notion that “there is no alternative.” How might you go about making your most persuasive case to conservatives and to cautionary rich people not that they should hate themselves, but that they should abandon the defeatist notion that “there’s nothing we can do about social classes, racial and wealth inequality, climate change, militarized borders, and war”?

Conservatives have been making the same arguments for hundreds of years. Albert Hirschman’s very important book The Rhetoric of Reaction describes these recurring conservative arguments. The futility argument (that you can’t actually change anything) gets made over and over and over again, every single time anyone pushes for serious social change. Now that doesn’t make this argument inevitably wrong in every given circumstance. But it should make us skeptical each time somebody dismisses our demand that certain people give up some of their wealth and power — because conservatives will respond this way no matter what.

And to be honest, I do sense something just terribly lazy and resigned and indifferent in so much conservative thinking. I take conservatives very seriously. At Current Affairs I have an entire giant bookcase full of conservative authors. It horrifies people who visit. I review conservative books. I understand their arguments. But I get angry over and over at how they reconcile themselves to a sense of hopelessness. I don’t see how anybody could assume we have no alternatives until we have made a very serious effort to find alternatives. I can’t accept when conservatives focus on the 20th century and say: “Oh look, we tried socialism. It failed. Hence capitalism forever” [Laughter]. I don’t understand how anyone could observe our miserable undemocratic workplaces and just consider these a necessary outgrowth of human nature. I don’t think that follows at all. Nobody should accept that stark conclusion on the basis of such limited evidence.

Again, I get from anarchists this resolution that says: “Well damn it, we’re going to try. We’re going to be careful. We’re going to learn lessons from what people have done wrong in the past. But we’ll never stop striving for something much, much better.” I mean, when you start to become a utopian, when you think about what the ideal society would look like, what it would contain — it actually doesn’t seem materially impossible, given all of the resources that this incredible, bountiful Earth gives us. George Orwell describes Earth as a raft sailing through space, with enough provisions for everybody. And I consider socialists humble enough to say: “We actually don’t know the limits of human nature, but we have a certain set of values, and we must try to actualize those values. Of course we don’t know whether we’ll succeed. But we certainly need to make every serious attempt.”

On the flip side, could we somehow get to your lovely little section differentiating conservationism from a voraciously exploitative conservativism? Could we bring in your apparent endorsement of a G.K. Chesterton-style “philosophy of caution” and advocacy of intellectual humility, and discuss why it makes sense for even a buoyant libertarian socialism to counsel: “until you understand why things are the way they are, be very careful about assuming you know better”?

Well first, I consider it important to distinguish between conservationism and conservatism because contemporary conservatism really doesn’t conserve very much. In fact, Friedrich Hayek wrote an essay explicitly titled “Why I Am Not a Conservative,” because right-wing economists believe in unleashing the creative-destructive power of the market, and the market preserves nothing. It will destroy everything you love. So I do want to take seriously conserving and preserving nature, beautiful human traditions, and the good things we have built.

Then as for the pragmatic parts of your question, Chesterton himself says something like: “If you come to a fence in the road, you actually should wonder why somebody put this fence there in the first place, before you start removing it.” Chesterton says that you need to understand something’s intended purpose before you tear it down. And I do think of that as a valuable piece of wisdom. At the same time, I think we should be careful not to let this principle of caution translate into a fundamental reluctance to do anything at all. Here again, I want to reclaim pragmatism. I talk in the book about pragmatic utopianism. I think we make a big mistake when we conflate pragmatism and caution and responsibility with inaction and centrism and so-called moderation. For example, I would describe single-payer healthcare systems as very pragmatic. We can see how well they work all around the world, right? We can empirically demonstrate that there’s nothing crazy or utopian about instituting a government-run healthcare program.

Or even for harder questions, like debates over speech restrictions, I think we can both move forward pragmatically and be cautious. Libertarian socialists have always warned to err on the side of free speech, because we believe very strongly in preserving civil liberties, because we’ve seen how fragile these liberties always remain. We’ve seen how societies can very easily lapse into authoritarian tyranny.

So libertarian socialists certainly have their cautious side. We don’t want to give too much new power to a state that always could turn and use that power against us. That’s the kind of cautious principle I find very valuable. Being radical does not mean being irrational. It doesn’t mean you just ignore the question: “Well, how will this really work?” That’s a crucial question, because our policies have to work, right? You need to think through hard questions like: “How do we best design this institution? How will we fund this institution? How do we ensure this institution doesn’t grow sludgy and bureaucratic? How can we guarantee that people who interact with this institution every day will have good experiences and not wait in long lines and fill out a bunch of confusing paperwork?” Authentic radicals who want to substantially improve people’s lives must ask all of those serious, pragmatic, cautious questions. But that questioning doesn’t need to translate as: “We should only ever take baby steps.” No. You realistically assess what could happen if you take course A or course B. And if course A looks better, and doesn’t seem to have major negative consequences, then you take it, even if it means a very serious change, because sometimes big change is actually pragmatic.

Finally then, perhaps indulging my own old-school pragmatism, could you point to a “more respectable liberalism” stemming from figures such as FDR? And could you again describe where you see such a vision still being insufficient? Or why would it not be enough for a resurgent respectable liberalism today to commit to a comprehensive renewable-energy plan, provide a stronger and more accessible and more inclusive social-safety net, end our shameful student-loan profiteering, promote successful job training/retraining, and significantly reduce certain corporations’ dominance (and corresponding income and political inequalities)?

A liberalism that had done those things indeed might have been respectable. If Barack Obama had been FDR, you might not have seen this current resurgence of socialism. One major limitation of this kind of politics, though, is that remains, at its core, elitist. I see that as the problem with Elizabeth Warren, for instance, who in many ways represents the kind of liberalism you’ve described. I see that as this kind of “West Wing politics,” where you get smart people in a room to come up with a list of the good policies, like the ones you mentioned. And I sense a couple problems with that. First, when you fail to prioritize democracy, and to ask people about their needs, your policies might look much better on paper than they do in practice — where they might have significant weaknesses. For me, this is the problem with progressive liberals who propose “public option” health insurance, or means-tested tuition waivers. In practice, healthcare under a public option will be a frustrating pain in the ass, and bureaucratic means-testing humiliates people.

But also, socialists doubt you can accomplish much unless you have a bit of the class analysis that often separates socialism and liberalism. We don’t just consider inequality bad because some people possess more stuff than others. We resist inequality because of the power relationships, where owners wield coercive power over workers, and landlords have coercive power over tenants. And in order to reduce corporate dominance, you really have to commit to changing who owns and controls corporations. Liberalism often still retains this illusion that the market simply needs proper regulation. But our problems stem from the very structure of the American corporation — not just from certain corporations gaining too much influence. The problem with Walmart is not that the US has too low of a minimum wage, but that as a workplace Walmart operates as a dictatorship in the interests of rich people.

However, if a liberalism came along genuinely interested in building a social movement pushing for the elimination of the capitalist class, and radical new measures on climate, workplace democracy, and healthcare, I would be all for it. At that point, admittedly, there wouldn’t be much to distinguish it from socialist politics, although socialists still have a long-term aspiration towards utopia — a plan for what to do after you get your basic social democracy established.