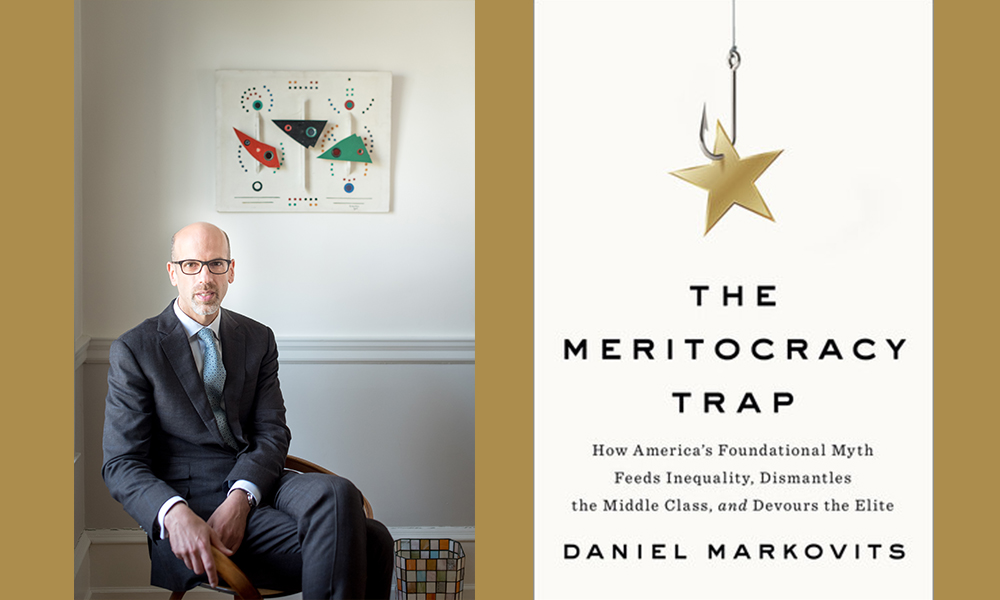

How might inclusive academic meritocracy help to launder sustained institutional exclusions and inequalities? How might meritocrats’ successes prompt not just interpersonal envy, but the occupational displacement of entire classes of workers? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Daniel Markovits. This present conversation focuses on Markovits’s book The Meritocracy Trap: How America’s Foundational Myth Feeds Inequality, Dismantles the Middle Class, and Devours the Elite. Markovits is Guido Calabresi Professor of Law at Yale Law School, and founding director of the Center for the Study of Private Law. He works in the philosophical foundations of private law, moral and political philosophy, and behavioral economics, and he publishes in a range of disciplines, including in Science, The American Economic Review, and The Yale Law Journal.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Could we start with your introduction’s claim that “Whatever its original purposes and early triumphs, meritocracy now concentrates advantage and sustains toxic inequalities”? Did any sustainable democratizing path forward ever exist for American meritocracy, before interlocking feedback loops of educational training, professional reward, and corresponding labor-market shifts started to entrench new disparities? Or could we never have constructed a sturdy meritocracy without giving rise to a self-perpetuating class of meritocrats?

DANIEL MARKOVITS: In its early years, meritocracy did help to open up the elite, and in that way it did provide a democratizing force. The mid-century American elite, especially at certain elite institutions, had a significant hereditary component. The college-admissions process even had this built into its language, as the sons of alumni fathers “put themselves down for” rather than “applying to” the college of their choice. The resulting elite was not particularly hardworking, not particularly ambitious, in many ways not particularly skilled. At a place like Yale College in the 1950s and 60s, the public-school kids received by far the best grades — having gone to a prep school made someone much less likely to earn a place in an academic honor society. People like Kingman Brewster of Yale, and presidents of Harvard a bit earlier, recognized this situation as unfair and dysfunctional. They sensed that opening up university admissions (and then eventually elite jobs) to effort and accomplishment would change who made it into the elite, which would make this elite function much better. So from 1950 to 1970, across the top American universities, the academic quality of their student bodies shot up dramatically. By the end of the 60s, the average student would have been around the top 10 percent of the class from the beginning of the 60s. In this way, meritocracy succeeded in raising standards and succeeded as well (although less immediately) in opening up the elite to historically marginalized and underrepresented groups: to Jews, to people of color, to women, all of whom could compete much more effectively on the merits than on inherited status and breeding.

Could a society get sustained benefits from this meritocratic approach, without getting the unintended consequences that the book describes? Honestly, I don’t know. Other societies have opened themselves up significantly through something that looks like meritocracy, without so far going down the hierarchical and exclusionary path that the United States has gone down. Germany for example has dramatically increased the number of people who attend university, and has opened up its most elite institutions to people who might not have made it in a prior generation, but does not seem to have yet produced the kind of self-perpetuating stratification (based, as you say, on training and on elite labor and income) that the US has.

Here it may help to draw a distinction between “excellent” education and “superior” education. Excellent education teaches knowledge and skills that make a person very good at something worth doing. Superior education makes its students better at something than all other people — regardless of whether or not that superior skill has any worthwhile application. Everybody, in principle, can get an excellent education. At times in America excellent education has been broadly distributed. But superior education necessarily remains exclusive and hierarchical. The American experience shows how quickly meritocracy can turn towards ruthless competition, towards relentless hierarchy, with an emphasis on superiority over excellence.

So here as we start to trace the mutually amplifying, institutionalizing, rigidifying drivers of later-20-century American meritocracy (again: not just coaxing forth internalized pressures amid high-performing academic echelons, but epitomizing much broader societal reconfigurations), could you likewise sketch how this book’s working definition of meritocracy might sit alongside slightly more concrete conceptions of automation, globalization, financialization — all perhaps first threatening industrial laborers, but now also threatening managerial and certain professional classes? How might you position these seemingly related socio-techno-occupational epiphenomena as causes of, as consequences of, and / or as coincidental adjacencies to, meritocracy?

At the most abstract level, I’d define meritocracy in terms of people’s getting advantage (income and status) based on their accomplishments rather than their inheritance or their race or caste. Then more specifically, today’s American meritocracy involves a hyper-competitive struggle all the way up the scale of achievement. That’s where I see the strongest connection to some of the other phenomena that you just mentioned.

Of course the particular dynamics of meritocracy will vary from case to case. But we can take financialization as an example that illustrates the general phenomenon. It might be hard to imagine today, but mid-century American finance work was not appreciably higher-skilled or better-paid than the rest of the non-agricultural private sector. Its basic model of production prioritized mid-skilled middle-class workers. And as finance’s output grew, so did the number of finance workers and their share in the overall labor force.

Then in the later 20th century, this model for financial production changed dramatically. Finance started becoming more and more skilled, and more and more highly paid. Since the end of the 1970s, financialization has involved this sector getting a bigger and bigger share of GDP, but with a stable (or even declining) share of employment — as relatively few super-skilled workers have replaced many mid-skilled workers.

Home-mortgage finance provides a case study that illustrates the broader trend. Home-mortgage finance used to employ large numbers of mid-skilled loan officers (college-educated, but not super-skilled, and well but not extravagantly paid) exercising professional judgment and discretion to make sure that individual loans would generate profitable returns. But today, home-mortgage finance operates very differently. A few highly skilled workers construct and trade derivatives based on loans that banks originate but no longer hold. The existence of these super-skilled workers makes it possible to deskill the loan originators, who have been reduced to filling in forms with machine-scorable data. The process no longer relies on such accurate decisions about individual loans, because securitization can correct for loan-specific inaccuracies later. So the rise of super-skilled Wall Street traders, and the demise of mid-skilled loan officers, go together. Analogous processes have played out in other sectors. Again and again and again, across our whole economy, we see super-skilled workers come in, strategically apply technological innovations, and dominate production — displacing mid-skilled workers and deploying relatively unskilled workers in their stead. We get a bifurcated workforce, whereas previously we had a workforce concentrated in the middle of the distribution of skills and income.

Here just to flesh out further the emergence of this new superordinate elite (as well as the impact of that emergence on the rest of us — perhaps starting in educational institutions, but soon enough reshaping broader workplace contexts), could you make the historical case for how, say, “financial engineering” becomes something more than a metaphor in the late-20th-century American economy?

Right, again I’d start from the broader point that super-skilled workers bend the arc of innovation, by inducing interested innovators to create new ways to deploy the skills that these exceptionally trained individuals now have. Finance, as it happens, nicely illustrates this mechanism also. The basic mathematics behind modern finance, including securitization, actually reach back to Pascal, who developed probability theory to start figuring out how to value what are in effect options (as it happens, for aristocratic gamblers). And by the mid-20th century, much of the modeling needed for modern portfolio theory existed.

But the basic science didn’t get deployed systematically until a bit later. The US victory in the space race, and the Cold War détente, left the country with a surplus of physicists and engineers, essentially trained to staff American physics departments and the military-industrial complex. These highly skilled workers needed to go looking for new employers. Eventually, banks realized that these workers had precisely the skills required to apply previously abstract theoretical ideas about how to value contingencies — in a practical and implementable mode of financial production. Securitization then started taking off. The first hedge funds arose. Eventually, financial institutions changed their whole organizational model. These new technologies of financial production dramatically increased the returns to high-skilled professionals. At the same time, they made mid-skilled finance workers surplus to production. And one can tell a similar story in law, in management, even in manufacturing or in retail.

Sure The Meritocracy Trap pinpoints, as the most dramatic manifestation of today’s labor inequalities, these increasing gaps not between an owner class and a worker class, but between a superordinate class of workers and an idled mid-skilled class of workers. So here could you situate this emergent disparity alongside more familiar Marxist rhetoric regarding a cartel of lucky / lazy capital-holders living off everybody else’s exploited labor? Where might your own diagram of today’s economic pyramid not look so different structurally from such Marxist models? Where might your qualitative account of today’s idled and elite working lives sound the most different tonally — with hyper-productive individual labor commanding ever-rising salaries, with such salaries in turn necessitating (for their own justification) ever-increasing labor (and with that exhaustive labor further confounding, alas, the most worker-centric moral cases for economic redistribution)? And how might your own analysis speak to the temptations many of us feel at present to identify clear villains, perhaps more than to grapple with “deep and pervasive dysfunction in how we structure and reward training and work”?

Conventional analyses do identify two rival classes, an owner class and a worker class. These analyses tell us that owners exploit workers. At present, that particular story often emphasizes a shift in national income away from labor and towards capital over the past 50 years. And I want to stress that this very real shift does account for some part of the broader rise in inequality. If you look at Bureau of Labor Statistics data (which present this shift as larger than some other competing economic analyses do), these suggest something like an eight-percent shift of income away from labor and towards capital over the previous half-century or so, followed by a slight shift back towards labor in the past couple of years. Even if you work from the eight-percent number, it becomes clear at once that this shift cannot account for most of the rise of top incomes overall. The top one percent of income earners own maybe a third of all capital. A third of eight is about two-and-a-half. But the actual increase in the top one percent’s income share comes to about 10 percent of national income. So roughly three-quarters of this increased top income share still remains unexplained.

I explain it by identifying a third class, a class of elite labor, that drives rising top incomes overall. Introducing this third class means addressing even more potential conflicts. Now we have conflicts between owners and workers, between elite workers and middle-class workers, and between elite workers and owners.

On my analysis, today’s main source of rising inequality (for now, at least in the United States) comes from the increasing dominance of elite workers both over middle-class workers and over owners. And the hollowing out of our middle class comes from this dominance of elite or superordinate workers over mid-skilled workers. A small cadre of superordinate workers captures most of the income from production, and a mass rump of less-skilled workers gets paid much less than they might have a few decades prior. But these superordinate workers also do take money away from owners. The book cites a study from around 2002-2003, in which the five highest-paid executives at each of the S&P 1500 companies (so just 7500 people overall) took home income equal to 10 percent of these companies’ total profits. That’s superordinate laborers taking surplus from owners. To understand rising income inequality, we need to document and analyze that part of the story.

Now, you also asked about responding to villains versus responding to structures. And the book takes as one of its basic insights that this superordinate class’s wealth comes less from physical or financial capital than human capital. This class builds and holds its wealth through its own training and skills. If you possess significant financial capital, you can gain income from it without working, because you can mix this financial capital with someone else’s exploited labor, and take a cut of the profits as your income. But if you possess human capital, you only can get income by mixing it with your own active labor. This requires the superordinate class to work exhausting hours (unlike preceding generations of elites, who could exist as much more of a leisure class). Today’s superordinate workers get paid on this basis of extreme productivity, rather than fraud or rent-seeking — which doesn’t mean this new elite earns or deserves every dollar it makes. So my book does begin by calling “merit” a sham, but blames today’s maldistribution less on aristocratic greed or exploitation than on the structural conditions you just mentioned.

So in our contemporary meritocracy, each generation must prove itself afresh, must demonstrate its own merit through its own accomplishments. But of course this sense of perpetual competition need not suggest that everybody starts off from (or ever could attain) an equal footing. So could we continue tracking how meritocratic inequality further exacerbates itself through the individual person — particularly through this person’s educational training, one domain in which meritocrats especially thrive? Could you outline how our ostensibly merit-based educational system itself allows (from pre-primary tutorials, to tax-exempt boarding schools, to extravagantly endowed universities) for a staggering transfer of sheltered wealth, status, and earning-potential: with superordinate high-achievers emerging as the beneficiaries, but also serving as the mules in this self-directed, self-instrumentalizing, self-alienating process?

First, we have this urgent instinct to associate meritocracy with equality of opportunity and with individual accomplishment. If you can judge people based on their accomplishments, certain other forms of exclusion and hierarchy determined by race or caste or gender should fall away. But such equality of opportunity did not endure in the face of meritocracy’s own successes. Today, only rich parents (meritocrats themselves) can afford to pay for the resource-intensive education needed for children to succeed in the next generation’s meritocratic competition.

Today, even before children get conceived, our meritocratic elite have made a series of decisions that massively privilege their own offspring. A college-educated person has become many times more likely to marry another college-educated person than they were at mid-century. These couples have a much better chance than other couples of staying married. Secure couples invest more time and money into training their children. Rich couples invest much, much more money on training their children, both outside of school and inside of school.

Rich public schools spend two or three times the median per-pupil rate per year. Rich private schools can spend five or six times as much per pupil. And all this investment produces enormous differences in educational accomplishment. Just to give one striking example of the elite effectively out-training everybody else: the College Board released a 2016 profile of its SAT takers. Roughly fifteen thousand SAT takers who had at least one parent with a graduate-school education scored 750 on the SAT verbal — roughly equivalent to the Ivy League median. But fewer than one hundred SAT takers with neither parent graduating high school scored 750.

If you want a broader illustration of the meritocratic inequalities associated with today’s educational training, consider the educational investment for a typical one-percent household and for a typical middle-class household, across each year of a child’s life. Then imagine taking this sum and not investing it in education, but rather putting it into a trust fund to give to the child upon the death of the parents (one way in which preceding aristocrats passed dynastic wealth down through the generations). You get an overall difference of about ten million dollars per child.

That amazing stat stood out in this book.

It confirms the dynastic features of our meritocracy. It helps to illustrate how meritocracy creates a competition in which, even when everybody plays by the rules, only the rich can win.

But you’ve also raised the question of whether we should consider this endless meritocratic competition good (in human terms) for the elite. And here I’d note that, with today’s intense competition, having rich parents provides a necessary condition but not a sufficient condition for ensuring you can make it into the elite yourself. You still face so much pressure to outperform everybody else, so that even with all this training, you still can fail dramatically. In one year during the 1990s, the University of Chicago accepted something like 70 percent of its applicants. Last year it accepted six percent. So the constant threat of exclusion and of losing caste remains quite real, even for the rich.

The strains of beating back this threat of exclusion harm rich children. A possibly deeper harm comes from the fact that, in order to succeed in these endless competitions, both parents and children must at every moment of their lives treat the educational process instrumentally, and treat themselves as the assets they own and manage in order to build up as much human capital as possible, and then deploy this accumulated human capital in whatever job will pay the most. This is a profoundly alienating way to regard your own childhood and your own work life — and it damages even (and perhaps especially) those who, by conventional measures, succeed. Middle-class workers, whom meritocratic inequality excludes from income and status, have good reason not to empathize with these elite problems. But that doesn’t make the painful conditions any less real to the elites who confront them.

As another way of seeing the burdens that meritocratic inequality imposes on even the “winners,” consider the deeply disturbing gendered patterns that arise when women drop out of the workforce (again especially the elite workforce) to raise children. Superordinate labor demands hours that are flatly incompatible with bearing and raising children. Moreover, meritocracy makes the household literally into a site of economic production (of the next generation’s human capital), overseen by an extremely expert worker. When overlaid by gendered expectations for women to do this work, meritocratic norms impose distinctive pressures on elite mothers to step back from their careers. Women who take on the role of the intensive helicopter meritocratic parent in effect engage in a highly skilled, extremely demanding, full-time job.

With women still stuck doing the unpaid labor.

Right, care work always has been under-paid, under-acknowledged — specifically in an economic order that associates pay with worth. But whereas unpaid care work historically took place outside the centers of economic production, today’s building up of human capital within the next generation actually does play a central productive role, while still getting so little economic credit.

So in terms of how meritocracy might both combat and reinforce (or reinvent) various forms of social stratification, could we also discuss its connections to contemporary populism? First, of course, one can wonder to what extent any mid-20th-century economic mobility itself remained the policed privilege of straight (or closeted) white middle-class males. But your book also raises timely, uncomfortable questions about how today’s elite’s “intense concern for diversity…carries an odor of self-dealing”; about how today’s “political correctness does not denounce calling rural communities ‘backward,’ Southerners ‘rednecks,’ Appalachians ‘white trash’”; about proudly inclusive educational institutions unable to resist erasing “first-generation professional students’ middle-class identities.” Here how might you most constructively appeal to a meritocratic elite to better recognize and rethink its own “chauvinistic contempt or even cruelty regarding inequalities that cannot be cast in terms of identity politics”? And how might such contempt or cruelty, particularly as directed at an educationally / occupationally displaced white middle class, at times not sound so different from a preceding Gilded Age’s elite blaming the poor for somehow “deserving” their dismal fate?

That question definitely speaks to the powerful role that diversity and inclusion and identity politics play within elite institutions today. And I’d argue that they play this role for two reasons — one of them laudable in a pretty uncomplicated way, and the other less laudable and more complicated. Most laudably, appeals to meritocratic diversity seek to address the huge amount of exclusion, oppression, and subordination along lines of race, sexual orientation, gender, and gender identity that we still see today. Elite institutions themselves have been deeply complicit in these historical forms of exclusion, and they remain complicit in such exclusions even now. Their commitments to diversity and to inclusion reflect a recognition of these facts, and a serious effort at a morally appropriate response. All of that is exactly as it should be.

At the same time, a less laudable part of this inclusive approach certainly does exist. If you look at institutions like my own, Yale Law School, we don’t operate as a foundationally apartheid institution any longer. So today we should work to overcome racialized subordination still within ourselves, and we can overcome this without fundamentally changing the kind of institution that we are.

But elite institutions, including Yale Law School, stand in a different relationship to economic inequality and to class. These institutions don’t treat class inequality as a contingent defect that they might overcome. Instead, they are based on class and economic exclusion: their social and business models require that they produce, sustain, and promote a socio-economic elite, which will work under conditions of meritocratic inequality and class hierarchy. And a deep commitment to racial diversity and inclusion (while right and proper on its own terms) also helps to launder this economic and class-based eliteness. It enables an institution like Yale (or for that matter Goldman Sachs) to say: “See, we have opened ourselves up and become equal and egalitarian. We promote people regardless of race or gender or sexual orientation, just on the merits.”

This allows these institutions to justify ongoing forms of economic exclusion, which I consider a real moral mistake. First, with respect to working-class and middle-class people, this outcome reinforces the false claim that, instead of structural exclusion, they face their own individual failures to measure up — a profound moral insult. And second, for those who do advance into elite institutions, meritocratic assumptions create a kind of smugness and unwarranted self-satisfaction, and mask the ways in which advantages and privileges possessed by superordinate workers connect quite deeply to disadvantages and harms imposed on the rest of society.

We’ve discussed how you, from your Yale Law perch, might speak to this meritocracy trap. I do wonder whether sustained argumentative opposition to meritocracy itself can resist being subsumed within a broader meritocratic enterprise (could one, for instance, characterize this book as a magisterial superordinate project seeking to subsume millions of gloomy anecdotal gripes into a glossier mode of expert-class social critique?). Or let’s say that most of your fellow citizens could read a sentence like “Meritocratic competition expels middle-class Americans from the charismatic center of economic and social life and estranges them from the touchstones by which society measures and awards distinction, honor, and wealth,” and, after sifting through some of its more abstracted formulations, could think: You can keep your meritocracy and your phony elite status-markers. Just stop giving rich people more tax cuts and loopholes, and leave me and my family and my community alone. What nonetheless made it important here to show yourself, in self-implicating fashion, writing from meritocracy, to meritocracy?

Well first I did just consider it important to own up to where I sit, for all the obvious reasons. This book definitely does not seek to hold up me or anybody else as transcending meritocratic dynamics. Basic honesty seemed to require acknowledging my own position, and inviting people to discount what I say based on the bias this position might produce.

Then in terms of writing to meritocracy, I do believe that, in general, structural social change requires persuading those in the elite, and in particular those at the outer margins of the elite, that this system doesn’t serve them well. I believe that structural change most often happens when this particular group peels off from the prevailing ideology. And today we’ve reached a situation in which even highly paid workers (law-firm associates who won’t make partner, for instance) can see quite plainly that this system does not serve them well. Even some of the partners (working one hundred hours per week into their fifties) have started to feel this system not serving them well. I sense those feelings now opening up possibilities we didn’t see before.

Of course, even more problematically, meritocratic inequality also hollows out the middle, and not just of the economic distribution, but of the social distribution — so that the person you imagine saying “Look, just make the income distribution a bit less unequal, and leave me and my community in peace” actually can’t rely on any stable, sturdy, middle class still being there. This is illustrated in the book by some reporting out of St. Clair Shores, Michigan, which I quite deliberately selected as a place once (but no longer) at the center of American economic and social life — and which today is not poor necessarily, but precarious. Here you can see any hope of just sticking your head in the sand, of just trying to smooth over the worst excesses and roughest edges of our current system, become increasingly not viable.

And here, as we start arriving at one of this book’s strongest possible moral (if not necessarily moralizing) arguments against today’s meritocracy (rather than against today’s elite), could you unpack the idea that “Elite education… does not just advantage those who get it but also harms those who do not, by making middle-class training and skills unproductive”? And again, why might targeted aid to the under-resourced, the under-privileged, the under-performing, not adequately address these structural distributions of present-day meritocracy? Why might we need more actively to bring meritocrats down a bit, rather than just providing more opportunity for somebody else to build themselves up?

One more prescriptive version of that question helps to fix ideas. Somebody could ask: “How about a universal basic income, at a relatively high level, providing financial security for everybody?” For various reasons I feel quite skeptical about that working well. I actually consider universal basic income an incredibly dangerous idea, because it immediately raises the question of who is entitled to this income, and pushes hard on questions of membership. That could only inflame nativism in the most extreme ways.

But then more broadly, I’d say that it took several centuries of sociological and moral development to create the regime we now have, in which a person’s social position and even self-worth come from her productivity, her industry. Today these values have deeply entrenched themselves in elite workers bragging about how busy they are, and in middle-class workers building their lives around expectations for dignified employment (secure, paying well, and allowing a person to do useful work). And the thought that we can just remake this value system so that people flourish while remaining in some fundamental sense unproductive or unnecessary strikes me as a kind of moral hubris. I mean, maybe over centuries we could remake values in this way. But public policymakers can’t just do that on their own. For a long time to come, we still will inhabit a world in which individual moral value, individual self-respect, and social respect all depend on productive work. So we need to restructure our economy and our labor markets so that people have opportunities for productive work — whereas meritocratic inequalities accomplish just the opposite.

So within an educational context, you recommend that we stop subsidizing an exclusionary meritocratic elite, by repealing tax-exempt status for well-financed academic institutions that fail to serve a compelling social interest — specifically those which do not draw at least half of their students from families in the bottom two-thirds of income earners (perhaps accomplished through a significant expansion of these institutions’ comparatively small student populations). Within an occupational context, you recommend that we require economic policymakers to proactively assess projected outcomes across a diverse range of job types, and more broadly to promote mid-skilled production and middle-class jobs through targeted tax incentives (for instance by eliminating the individual cap on the Social Security payroll tax). Here could you offer your most persuasive case that such proposals do not seek to pursue some zero-sum competitive edge for one economic class pitted against another, but actually to serve the long-term interests of society as a whole? How to convince, say, those whose academic performance already would have gotten them into Yale (and from there to Goldman Sachs) that they will gain more than they lose here, even if their own status does become a little less elite?

First, that’s exactly right. If the mechanism of meritocratic inequality involves two movements (the concentration of training in a narrow elite, and the remaking of work to favor precisely the skills of this superordinately trained elite — to the detriment of everybody else) then, if you want to unwind this inequality, you’ll need to focus on reversing both of those movements.

So on the education side, the book recommends dramatically expanded access to elite education, and dramatically reduced differences between the educational investments made in the richest families and in everybody else. A university like Princeton in some recent years has received an implicit public subsidy (through its tax exemption) of something like one hundred thousand dollars per student. The State University of New Jersey at Rutgers receives around twelve or thirteen thousand dollars per student, and Essex County College in Newark receives about two or three thousand. So the very rich kids at Princeton (with more students from the top one percent than from the bottom 50 percent) get these massively disproportionate subsidies.

From us.

That’s right. So we can’t just create fairer competition for a very small and narrow educational elite. We can’t just force elite universities and private schools to diversify (by race or class) their student bodies. We need dramatically to expand the number of people who have access to high-quality education.

And there’s no reason that our most elite schools, at all grade levels, can’t double their enrollments. The Ivy League today spends almost twice as much per student per year as it did in 2000. Collectively, university education in the US spends much, much more (in real terms) per student than it did in 1980. And whereas from the end of World War Two until the mid-1970s, this country roughly quadrupled the share of its population getting a college degree, we’ve had only very slow growth since then. There is no reason we can’t commit today to doubling the share of Americans who get college educations. This would in fact make education, again, more broadly excellent — and much less committed to zero-sum superiority.

And what corresponding shifts would you hope then to see in labor markets?

Right now, we systematically favor production involving small numbers of superordinate workers over production involving large numbers of middle-class workers. We have created multiple incentives to replace, say, 20 people who make one hundred thousand dollars a year with robots and computers and one person making two million dollars a year. We need to undo that, and the book’s payroll-tax proposal offers just one approach. The payroll-tax base gets capped at about one hundred thirty thousand dollars, which means it taxes superordinate workers at a much lower percentage than middle-class workers. Indeed, middle-class labor is overall the most heavily taxed factor of production in the entire economy — which is absolutely crazy in an era with a struggling middle class. Corporations in effect pay a tax penalty today when they promote mid-skilled employment.

A field like health care illustrates these labor-market dynamics at work. We can deliver health care using many different models. Right now, our model emphasizes superordinate specialist doctors and high-tech interventions, but we could probably deliver better health results using a model that emphasizes nurse practitioners, dietitians, public-health workers, and fitness trainers. And here again, we should think of promoting public health not just in terms of improving patient care, but also in terms of more broadly improving public-health outcomes through labor-market interventions.

You could say something similar for law. You could say something similar for finance. Regulation that discourages securitization, that separates commercial banking from investment banking, that supports local banks, that encourages banks to make loans and then to service these loans rather than selling them — all of these regulations would have the consequence of favoring mid-skilled financial workers, as well as serving a broader public interest by making our financial system more stable, less prone to crises, less susceptible to fraud or rent-seeking from the top.

And when you ask about what makes such policy approaches also good for elites, I’d return to the exploited and alienated professional lives of even very, very rich workers. I wouldn’t make a very subtle plea, but rather a direct one. I’d say: “If you make five million dollars a year working 85 hours a week under conditions over which you have no control (because the market sets them for you), you’d be much better off earning three million a year, working 60 hours a week, on tasks (some of which at least) you can choose. In terms of real human flourishing, the value for you of making two million dollars more is basically zero, and the value of having more time and more choice would be enormous. And if, as a member of today’s elite, you believe you somehow can have both extravagant income and dominant status while retaining your authentic freedom, you’re fooling yourself. The structure of today’s capitalism ensures you only can get super rich off your human capital by exploiting your own alienated labor.”

Sigmund Freud’s notion of a narcissism of small differences traces an oft-repeated pattern in which an elite’s most acute status differentiations provide much more potential for painful intra-group rivalries than for satisfying accomplishments or tangible enhancements to one’s quality of life — and with anybody outside such micro-communities struggling to see why any of it matters anyway. To what extent does that perhaps more general civilizational discontent overlap with what you see happening in American elites’ inner lives today?

It absolutely overlaps. It takes us back to how, particularly in a meritocratic regime, status has such a precarious, zero-sum quality. Even within the elite, each person’s triumph comes on the back of many other people’s failures. And this phenomenon, to some degree inevitable in any human society, picks up added pressure under intense and pervasive competition. I truly believe that the elite, as a whole, have a collective class interest in protecting themselves from that. I mean, in a way, the leisured norms of the old aristocratic class actually helped to protect them from this kind of ruinous intra-elite competition. But the work lives of today’s meritocrats offer just the opposite. Instead we see ruinous competition within, say, Goldman Sachs — among people who already earn so much that the idea of taking more from each other seems (from the outside) just absurd, but still feels (from inside this economic structure) somehow irresistible.

And where does Bourdieu (perhaps even more than Marx) then figure into this book’s broader lived critique? To what extent have we been discussing this whole time a new exclusionary bourgeois habitus masquerading as moral / natural meritocratic order?

I think there’s a lot to that. I would say that the social and economic operations that the book tracks all are rationalizable within existing models of neo-classical economic thought. So in that sense, I want to resist the need for adding more intricate socio- or psychological accounts. But I also agree that, at a greater level of abstraction, Bourdieu’s study of social distinction overlaps with much of what this book describes.

Bourdieu’s work even foregrounds the instrumentalization of elite education as distinction’s basic driver.

Right.

So to close then by returning to our own present: in an age of existential climate-change threat, of high-stakes engineering and decision-making around AI technologies, of any number of persistent (and / or pressing) human and ecosystemic crises, we of course don’t want to lose out by overshadowing and overlooking the merits of huge classes of people. At the same time, I’d assume that we don’t want to check too much whatever most outstanding capabilities certain individuals possess — or, likewise, whichever social structures (while no-doubt unpleasant in certain ways, unfair in certain ways) have offered some of the best means for harnessing and cultivating talent that humans have so far hit upon. So here could you sketch any positive traits, habits, capacities, distinctly cultivated through our present meritocratic system, that you would in fact hope for us to preserve, and perhaps to popularize, rather than to abandon altogether alongside today’s meritocracy?

Yes, I do want respectfully to acknowledge this incredibly dynamic, energetic, creative, productive elite — possessing truly impressive capacities, and sometimes cultivating excellences that our society needs. But, at the moment, many of this elite’s most outstanding capacities don’t get directed in particularly socially productive ways. I mean, if you think of all the energy deployed right now towards financial engineering, towards genuinely remarkable advances in how to manipulate contingent financial claims, how to allocate capital, how to control the real economy by owning what are in effect promises (or purely abstract legal creations) — almost none of these elaborate efforts produce real positive social product (as opposed to purely redistributive shifts), right?

Again, I could make a similar case for law. Or even in a field like medicine, where we have astounding innovations and advances, we live in a society that can transplant hearts, that can implant a robot heart — but we don’t really yet know, for example, what optimal exercise patterns might look like. Should I exercise intensively one day a week, or moderately three days a week, or modestly every day? Our medical community still hasn’t come up with a clear answer on that. But such an answer would improve our population’s heart health much more than many new extremely costly innovations in artificial hearts. So even in places where elite dynamism does produce what look like real advances, we could come up with counterfactual scenarios producing much more valuable advances. And that’s why I believe we have to acknowledge that, yes, superordinate workers have gotten really good at some things, and at some things worth keeping — but the mere fact of an advance doesn’t mean we couldn’t come up with much more socially productive advances in a much more equal society.

Photo of Daniel Markovits by Stephanie Anestis.