As soon as Christina Hammonds Reed’s debut novel, The Black Kids, was announced, I couldn’t wait to read it. Black girl coming-of-age story? Check. Set in my beloved Los Angeles? Check. A historical look at the 1992 LA uprising? It’s the book I never knew I needed all these years.

I was lucky enough to get an early read, and beyond thrilled that the novel was, indeed, exactly what I wanted in YA fiction. Painting a complex view of a wealthy Black family, and focused on high school student Ashley, The Black Kids skillfully explores complicated themes of identity, race, class, and stereotypes.

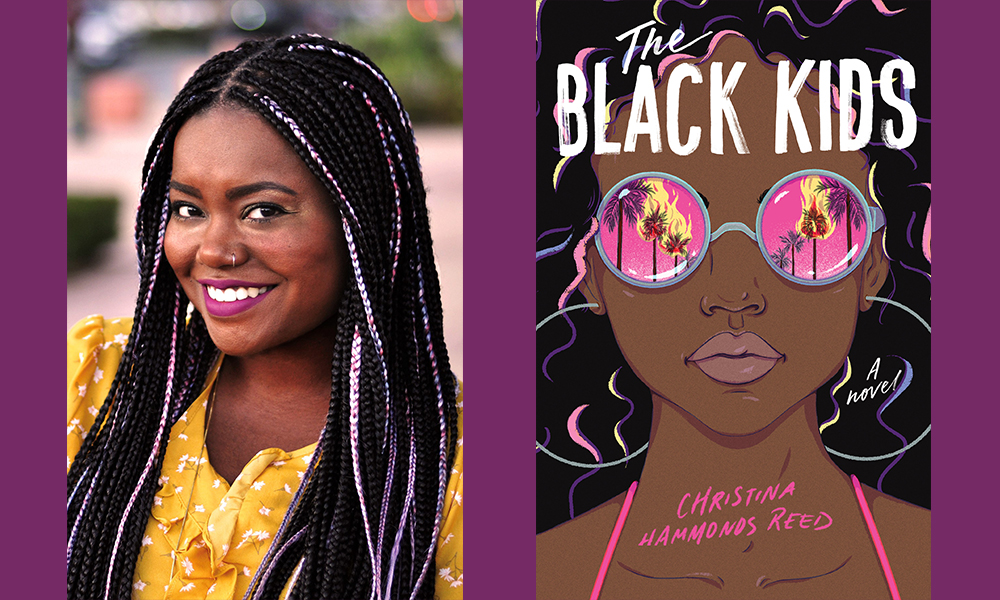

Christina Hammonds Reed holds an MFA from the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts. A native of the Los Angeles area, her work has previously appeared in the Santa Monica Review and One Teen Story.

We conducted the following interview via email.

¤

BRANDY COLBERT: The Black Kids was expanded from a short story originally published in One Teen Story back in 2016. Why and how did you develop it into a novel?

CHRISTINA HAMMONDS REED: When “The Black Kids” short story came out, I was approached by several agents who were interested in me as a storyteller and the potential in the material. I eventually went with my agent, David Doerrer, because he 100% understood what I wanted to achieve as a writer, the stories I was interested in telling, and was genuinely invested in developing the manuscript that would become the novel with me as somebody who had never written a novel before. It felt like with the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement at the time the story was published, there was so much more to say about unequal policing and the legacy of systemic and institutional racism and how that impacts black teenagers and families regardless of gender identity or privilege.

One thing I’ve found interesting about having a political book of my own come out this year is how many people have commented on its “timeliness,” in part because of the uprising and widespread protests against police brutality. I’ve seen early readers of your book say the same thing, though The Black Kids was also written before anyone knew what 2020 would look like. So, why did you decide to set the book during the 1992 Los Angeles uprising? Was there something that sparked the idea to revisit this time in history?

I wanted to examine race, class, and privilege against the backdrop of a time of huge racial reckoning in this country. Originally I wanted to look at Ashley’s relationship to Blackness and how during these times where race and unequal policing are at the forefront of the national conversation, many of us as Black people are engaging in these very personal questions about our own connections and responsibility to our community, and what community even means when you’re a Black person living in predominantly non-Black spaces. I started it in the Obama era and meant to use 1992 to hold a mirror up to the present. Especially as there was this narrative being pushed that the US was post-racial, but also as the BLM movement got underway in response to the deaths of Black people at the hands of police and white would-be vigilantes. We found ourselves 20-odd years after the riots still grappling with the same issues we were in 1992. It’s a continuum, right? There’s a direct connection between the George Floyd protests in 2020, the 1992 LA riots, the 1965 Watts riots, and the race riots where Black communities were destroyed by white mobs in places like Tulsa and Rosewood, just to name a few. To understand the past is to understand our present and I’m firm believer that arming ourselves with a knowledge of our history is one of the best ways to be the most effective advocate for change. That said, while writing I had no idea just how much it would relate to our actual present at the time of publication!

One of the many things I admire about this novel is its honesty. Ashley is not always the most “likeable” character, which instantly makes her compelling to me. I cringed while reading so many of her thoughts and decisions, yet it was true to her character and she was allowed room to grow. What were your favorite parts about writing Ashley? And what were the most challenging parts?

Ashley isn’t necessarily the traditional Black female protagonist that we often see in novels. She’s not rooted in the South, or New York, and she’s coming from a very privileged background here in LA. In many mainstream television shows, films, and books, Ashley would be the Black best friend, the sidekick. Clueless was one of my favorite movies growing up and in starting to write Ashley I was thinking of what Dionne’s experience of her world would be. What if she were the star of her own movie? How she would have responded to the events of 1992? Ashley has a ton of agency and drives the story both in her failures and in her successes. It’s one of the things I absolutely love about your writing as well! You write so beautifully the complexity of Black girlhood. I wanted to write a Black girl who was able to be vulnerable, who didn’t always do the right thing, who defied the oftentimes damaging stereotype of the “strong Black woman”, which in many ways denies us our humanity. Growth is so fundamental to being human and to being a teenager. Ashley’s discovering her own blind spots and failings and learning how to be a good friend, sister, daughter, advocate, and really just figuring out how to be a good person throughout the novel.

The most challenging parts I think are also some of my favorite parts in that Ashley is so not how I was as a young person, but a lot of her concerns were my concerns as a Black girl in predominantly non-Black spaces. Ashley can be very selfish, and self-centered, not as engaged in the world around her as she should probably be. She deeply hurts people she cares about in the text. I think it was a struggle making sure that readers understood that a lot of why she behaves the way she does is rooted in her being lost as a person. That she’s struggling to find the right people to cling to and in so doing makes some huge mistakes along the way, but ultimately she is somebody who wants to do and be good.

Ashley struggles with her identity as the only Black girl among her wealthy white friends while also feeling left out from “the Black kids” at her school. This may be, in part, why she spreads a rumor about one of the other Black students in relation to the looting that took place after the acquittal of the cops who brutally beat Rodney King. Can you talk a bit about how Ashley feels torn between these two different worlds, the class differences explored among the Black community in LA, and how that leads her to make a statement that she ultimately regrets?

So often Black people are portrayed as a monolith, but somebody who grows up in South LA will likely have an entirely different childhood than somebody who grows up in Bel Air, even with that shared experience of being Black in Los Angeles. Privilege and class factors considerably into how Ashley’s viewed herself up until this point. She thinks she has far more in common with the white friends she’s been besties with since kindergarten, and in some ways she does. But she herself also harbors this deeply rooted internalized racism which manifests in the rumor she accidentally helps start about LaShawn. It isn’t until the city itself is forced to confront its history of ugliness and systemic and institutional racism that she really begins to understand herself within the context of that history, to decolonize her mind, and to celebrate the beauty of what it means to be a Black person even in the face of intergenerational trauma.

Ashley has complex relationships with her mother, older sister, and cousins, in particular. What were you exploring here with the portrayal of so many different Black female relationships?

I wanted to capture the complexity of mother-daughter relationships, sisterhood and what it means to be family in general. I think many of us have complicated relationships with our parents or siblings at various points throughout our lives and struggle to understand each other in the wake of personal and generational differences. That’s only compounded when you factor something like mental illness, past traumas, Black identity, class, and respectability politics into it. There’s this deep, deep love between all of them, but they don’t always have the words or they have all the wrongs words. Throughout the book these women try to communicate and fail miserably and often, and their frustration with each other is palpable. All of which leads to some serious consequences, but also to a lot of growth.

I moved to LA nearly 20 years ago, and I am fiercely protective of it, yet I know it’s not a perfect place by any means. Your book reads as a love letter to Los Angeles, acknowledging all its flaws and examining the many different ways people live in this city. As an LA native, what was your experience growing up in Los Angeles? Do you ever find it difficult to write about an area that you have so many ties to?

I grew up in the suburbs of the 626, went to both private and public schools all over the place, then to USC for college and grad school. As an adult I’ve lived everywhere from South LA near campus, K-Town, Hollywood, Silver Lake, and at the moment, Hermosa Beach, and I’ve loved each place I’ve lived for very different reasons.

Writing about Los Angeles is difficult only in that I want to honor and do justice to this city. Portrayals of LA are so often super reductive and dominated by either this idea of LA as this vapid botoxed celebrity/influencer city, or of this gritty violent place, and the reality is both somewhere inside of that and very much entirely outside of it. There are so many different kinds of people who call this place home, so many cultures that contribute to who we are as Angelenos, and I wanted to celebrate the ethnic, religious, socioeconomic and cultural diversity that is at the heart of the beauty of Los Angeles.

To further the point, when people think “California girl” the immediate connotation, especially at the time in which the book takes place, is/was that of a tall tanned beach blonde, a thin white girl. That’s never actually been true. Who does that image serve? Who really is a California girl? I am. I’m none of things. Native California girls as I know them are not only white, but also Black, Latinx, Asian, Indigenous and Middle Eastern. We’re Muslim, Jewish, Christian, atheist, Sikh, and Bahai. We’re short, fat, skinny, tall, cis, trans, and everything in between. Ashley is very much an Angeleno and a California girl, and I wanted to celebrate our ownership of that moniker as well.

I’m sure that I, like many other people who’ve read your debut, are anxious to know what we can next read from you. Can you give any hints as to what you’re working on?

I’m working on an adult book that examines the nature of what it means and has meant historically to be a Black performer in this country, and the success and perils of that particular version of the American Dream. It’s about a family aspiring to be a group along the lines of the Jackson Five and how that impacts them as a family unit over the course of several decades. Also, it’s about Black boyhood and the beauty of the Black family, because at the end of the day I’m so fundamentally drawn to telling stories about the myriad ways in which Black people love each other.

Photo of Christina Hammonds Reed by Elizabeth T. Nguyen.