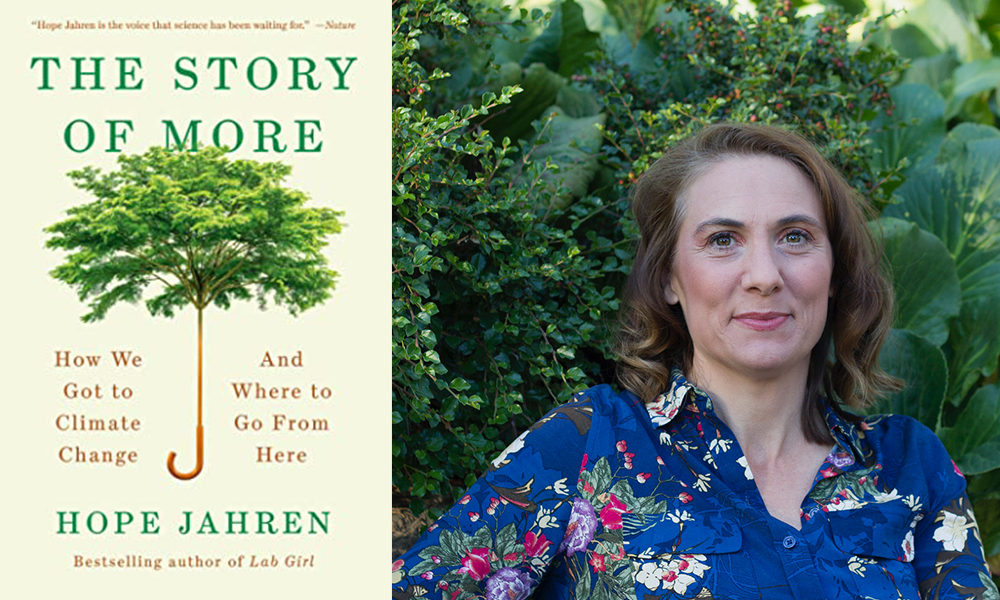

In 2016, Hope Jahren delighted us with Lab Girl, a memoir about plants and her life in science. In her latest book, Story of More: How we got to climate change and where to go from here (March 2020), she takes on those human activities that contribute to climate change, interweaving her signature prose — powerful sentences, personal stories — with numbers and statistics. Her aim is to help us viscerally grasp how our daily activities are implicated in what is to come.

Jahren is a geochemist and geobiologist at the University of Oslo in Norway, one of the countries in Europe that has dealt swiftly and strictly with the Covid-19 pandemic. We caught up with her on March 19, 2020, a week after the Norwegian population had been asked to shelter at home.

¤

VIVIANE CALLIER: Before we get to your book, tell us how cultural differences are shaping Norwegian as opposed to American responses to Covid-19?

HOPE JAHREN: On March 12, we were told that the university was closing and that everyone was to work from home. We promptly shut down the lab. It’s tough: this past week has been the longest that I’ve been away from the lab for maybe 30 years, except when I’m gone to do field work. But there’s no question that it was right to act immediately.

One thing I have been really impressed with is how quickly and seamlessly the schools got the kids online. Here, you have the same teacher for all subjects from grade one to grade seven, and social cohesion is a priority. Kids in any given class know each other really well and have a sustained relationship with their educator. By the time this virus happened, that strong social fabric could be readily transferred to online learning. In other words, the focus on community, which started long before I was born, became an incredibly useful tool in this new context.

One thing to remember about Norway is that it is a small country. We’re five million people, which is the population of metropolitan Atlanta. Organizing and effectively putting out a recommendation that people buy into is a fundamentally different proposition with five million people versus 327 million.

The other thing to keep in mind is that Norway maintains five national universities, a postal system, stock market, its own currency, newspapers, a military, and a hospital and emergency system. With only five million people doing all this, Norwegians are necessarily incredibly hardworking. A large proportion of them work for governmental agencies. So the government isn’t this abstract entity a thousand miles away in Washington making decisions and sending them down from on high. Here, people trust the government to make the right decision because it’s their uncle and cousin who work there.

Norway has grappled for a long time with how to preserve its culture and language in the face of globalization. There has always been a plan for protecting what we have. As a case in point, Norway has a seed bank. If the world is reduced to ashes, a bunch of Norwegians are going to crawl into that thing and come out with a handful of seeds and restart civilization. That seed bank, an expensive resource to build and maintain, is a beautiful example of Norwegian optimism and sense of social responsibility.

In your book, you talk about the changes related to food and energy production of the last 50 years and how these have altered our world and climate. They have also contributed to the rapid spread of Covid-19 — can you say more?

My book is about how the world has changed over the last 50 years because I turned 50 and wanted to figure out what it has meant to be alive during these 50 years as opposed to any other 50 years. Lab Girl was about my making sense of my own life. The Story of More is about my trying to make sense of my time.

I started looking at global change in the most literal terms I could think of — in terms of numbers, and these are the key stats: the population has doubled in the last 50 years, but food production has tripled, and fossil fuel use has also tripled. If we’ve tripled fossil fuel use, we’ve also tripled how much moving around of people and goods we do.

Fifty years ago there were about 26,000 planes taking off every day. In 2003, the year that SARS was such a problem, there were about 58,000 planes taking off every day around the world and about 2,900 of those were taking off in East Asia. Today, 100,000 planes take off every day and 15,000 of those take off in East Asia.

Coronavirus was a local problem that quickly became global for obvious reasons: the pandemic is an indirect result of ever-increasing consumption and travel.

You argue that we already produce enough food and energy for everyone on the planet but these resources are unevenly distributed, so some parts of the world live in excess while others lack the basics. What can we do to improve health equity?

These numbers are terribly interesting. I was calculating all this stuff from basic numbers provided by different agencies, which I really love doing. When I started making the calculations around how much food the world produces, and how much that amounts to for every single person, I did the calculation many times over to get it right. I finally convinced myself that if you equitably distributed the world’s food supply, it would be more than sufficient to feed the entire world according to USDA values. The problem is not the Earth’s inability to produce, but people’s inability to share. In some ways, share is too simple a word. I’m after a much more aggressive and collective definition of share.

Your recommendations are mostly focused on what individuals can do to mitigate climate change. But some readers might doubt the impact of individual action, believing that government regulation and policy changes are also necessary. Why did you choose to focus on individual action?

Policy is basically a euphemism for “telling people what to do.” This top down approach doesn’t seem to be going anywhere. It’s magical thinking to believe that sweeping policy changes will come down from on high solve the problem for us. For example, the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Climate Agreement have proved aspirational more than anything else.

Having spent so many years in the classroom as a teacher, and being the daughter of two teachers, I believe in “the hearts and minds” approach: people can change their ideas, and ideas change person by person. The first step is for people to be aware of how much energy they consume. I really don’t think they are aware. I believe that if people understood just how much they consume, they would be willing to consider live differently.