Yelena Moskovich’s opening scenes plunge. Her 2016 debut novel The Natashas opens with a confined crowd of young women with a shared name. “In the box-shaped room, there are no windows, there is no furniture. On the floor, blankets are spread one next to another like beach towels.” Moskovich’s 2019 follow-up Virtuoso opens with the discovery of a dead body: “Just one hand drooping off the side of the bed, resting on the bristles of the rose-colored carpet, fingers spread, glossy nails, raw cuticles…” Her new novel A Door Behind a Door opens with a stabbing and a punctured scream. “It wheezed. It lacked its high notes. It fell out of her mouth like a dog’s tongue.” Moskovich’s writing is sensory elevated and electric. This immersive and propulsive method is a gorgeous habit that follows in nearly every passage of her work.

Moskovich was born on the northeast border between Ukraine and Russia when it was still all the Soviet Union. In 1991, at the age of seven and ahead of the imminent Soviet fall, Moskovich’s Jewish family fled, on a migration pathway that eventually led them to Wisconsin, where Moskovich grew up. Later, she continued to Boston. Now she lives in Paris. Surely part of the reason Moskovich is so skilled at recurringly and evocatively dipping the reader into unusual yet fully realized sensory spaces has something to do with her own submersion into new worlds.

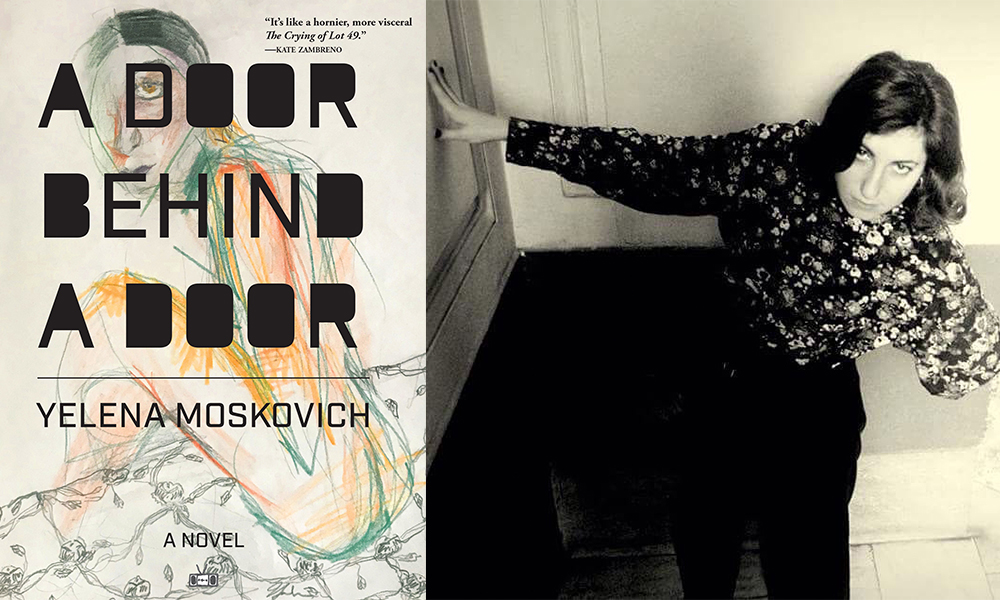

I wrote to Yelena Moskovich to ask her about submersion, slapstick melancholia, and her new novel A Door Behind a Door.

¤

NATHAN SCOTT MCNAMARA: I’m struck by the speed and propulsive quality of your writing and the way each word and moment swings into the next. How do you establish your rhythm while you work?

YELENA MOSKOVICH: The rhythm of this piece, as with every piece of my writing, is essential. It’s the heartbeat, and when I hear it, I know that the text is alive. It’s not something I establish because it cannot be authored. I get a feeling for how the text will move, it’s a sensation something like remembering, something like wishing, I am remembering or wishing for a heartbeat, like the loneliest lonesome loner being lovestruck for someone that does not yet exist. Every teenager knows the feeling of a love for someone they have yet to meet, so guttural, it creates flesh and history out of every banality. Finding the rhythm of a text is perhaps being that teenager, being so alone in the vastness and then… composing… love… out of thin air.

A Door Behind a Door toggles rapidly between all-caps headline statements followed by compact prose passages, and the technical format of the novel in this (and other ways) is inventive. How did you arrive at this form and why was it a useful design?

I was thinking of novels in verse, Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, and more contemporary experimental ones like the erotic thriller The Monkey’s Mask by Australian poet Dorothy Porter. I was thinking of the whole Russian heritage of lyricism and its taut liminality between melody and mathematics. I was thinking of the way we breathe when we are screaming, or crying, or swearing or avowing, or when we are terrified. I wanted this novel to have such lungs. Syntactical lungs that breath the text with this level of involvement or subjectivity. I wanted language that takes itself utterly to heart.

In addition to being lyric and innovative, your novels are also very entertaining, and they share plenty in common with thrillers and mysteries. How do you think about baseline pleasure when you’re writing? How does that correspond to ingenuity?

I have a lot of fun writing. I’m like a kid who wants to play. And kids play out strikingly philosophical and existential situations. They are Beckett. They are Brecht. They interrupt the story midway, change, shift, adapt, transform. They are also Sarah Kane. And Jean Genet. And Sophocles. They are not limited by our preconceptions of narrative, though they use them with frightening glee. They eat up our world. I’m like this hungry kid. I want to eat up all these ways of playing around me, all these genres and styles and forms and I want to PLAY. I don’t wait to be invited. I barge in. I hold my fingers up and I say, Look I am a murderer! I lay down on the floor and say Look I am a corpse. Because playing is a sort of jazz towards the essential, a calling out of the simulacre, of peeking behind the curtain in front of our own eyes.

In A Door Behind a Door, you write “ALL IMMIGRANTS ARE CHARLIE CHAPLIN.” How does this idea correspond to the members of the Soviet diaspora in this novel?

Charlie Chaplin was the master of slapstick melancholia, which is what I aspire to, which is also the natural character of immigrants. Things are funny. Things are sad. We fall down. We get up. That’s the basic four-step. But for me, immigrants dance these steps with heartbreaking sublime tragedy. They continue in Charlie’s footsteps, and Charlie continues in ours.

You quote Fyodor Dostoevsky in your epigraph (“Be bad, but at least don’t be a liar”) as well as in other places in the novel. What influence does Dostoevsky have on this book?

It’s not so much Dostoevsky as the Russian canon or the Slavic cultural character of the “bad soul.” Unlike Anglo-Saxon or Latin cultures, Slavs do not fear “badness” because we know we all have it in us. But we carry this knowing with a sort of melancholia, a lyricism of the fact, and we live with this slight tremor, that we might be bad, very bad, very, very bad, we might well be, even in the seemingly purest acts of love, especially in those acts of love. We are bad not from intention necessarily, but from the darkness of the night, the winter’s death of plant life, from the hunger and the prey, we are bad from our own beauty. We live with it because we must. But the one thing we cannot live with is… dishonesty. That is worse that badness. That is a horrible, abject state of a person.

You worked on this novel throughout pandemic confinement. What were your methods for staying creatively sand cognitively fit?

I find writing not too difficult. I find living very hard. I had many things in place to take care of myself and particularly my mental health, which is particularly sensitive, during this time. Some of these things were naïve or wobbly attempts at self-care. Others were protective and nourishing in the long game. But the writing happened as it happens, in intuitive doses, from a human who was at times quite whole and other times so broken wholeness seemed impossible, but then the horizon was where it was the day before, and so the writing went on, and the human went on trying to find wholeness.

In another interview, you say, “I’m not someone who does a lot of planning or structuring ahead of time. In fact, I do barely any. The body of the work grows as a discovery.” When you move forward with each piece of a novel (or if you circle back) how do you ensure your sense of continuity?

The beauty of continuity is that it is guaranteed in a sense. Since I’m the same person who is writing it. But the other definition of continuity that writers or artists are made to worry over is an imposed continuity — the type of near-legal jargon to survey that nothing is “out of place,” that the red cup in scene 1 is there in scene 7. But this is not a fundamental law of art. It is a human-made rule, it is: an opinion. That’s all. And here’s my opinion: what if the red cup isn’t there in scene 7? What if things fall out of place? That is also continuity. Just a different sense of logic or order. I think we can allow for a much wider spectrum of multiplicity in the narratives of art. We think multiplicity is about getting different people to tell their story in the same way. But it’s about the variety of human continuity. It’s not enough to seek out to publish overlooked voices (POC, queers, immigrants, working class, different walks of life, you get the picture) — when they are expected to “tell the world their story” in the same narrative terms as were used to eradicate and neglect their story. It’s not about stories. It’s about language.

What are your tools for making novels? Have they evolved or changed over time?

If I opened my toolbox to you, you’d look inside and say: but there is not a single practical tool here. What are these weird scraps and collected rocks and sandy seashells? That’s my fair warning. My toolbox has nothing that has to do with craft, so it may appear extraneous to the craft-seeking eye. When I write, the most important thing is how I feel when I’m writing. The form and content will take care of themselves. And there’s a scrap of paper in that toolbox too and it says, “You only have this life. Be honest.” (Slavic liability.) I try to be as honest as I can. To go from one feeling to the next, and stay in the feeling, not skip ahead, not wander back, but just take the risk to really feel each moment. The novel will be a mirror of the process anyways, so there is no point for me to think about “the novel,” only to be daring enough to feel the words with my utmost honesty.

Speaking to your life passage through various countries, languages, and cultures, you mention you like English as a way to hold many languages. What is it about English for you that makes this level of versatility and flexibility possible?

I like that English is a non-patrimonial type of language. Because it’s not necessarily tied to a national identity or cultural heritage as much as other languages are. Like French, for example (they are so precious with their precious French there is the Académie Française to regulate what new words can be accepted into the language). The English language, by it’ sheer global practicality seems to be divorced of a cultural obligation to represent. It is just… language. It is pieces of sentiment ready to communicate. Perhaps that’s why I feel so free in it. I don’t owe anyone anything.

You move not only geographically and linguistically, but also between creative mediums. Do you sense further movement ahead? What are you working on next?

I’d really like to write a film or TV series. To be continued. Otherwise, I just finished a short story collection I hope to get out soon, it’s something I’ve been working on alongside other projects for a while now, and I’m quite eager to share! (Soon being a very stretchy placeholder of time.) I also continue to make art. Art that’s vulgar and sentimental.

What have you read lately that’s changed something about the way you’re thinking?

Etel Adnan’s Shifting the Silence. Kate Zambreno’s Drifts. Chantal Akerman’s My Mother Laughs.