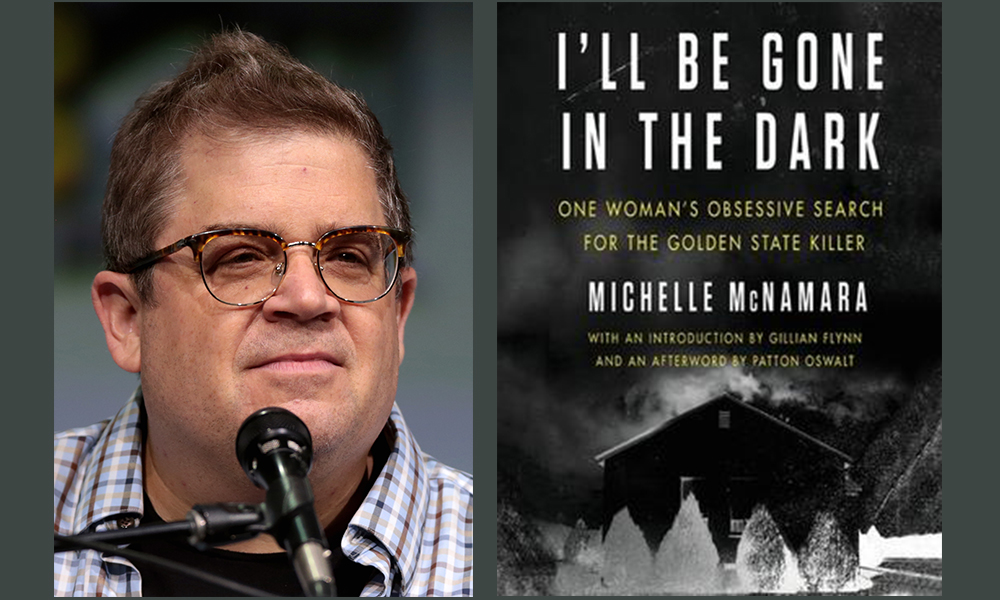

The inside of a fridge in a brand new house in Irvine, CA, in 1981 “smelled like plastic.” In Goleta, the same year, “the smell of night-blossoming jasmine drifted in through open windows” and “the hippies weren’t young anymore. Up close, you could see that they’d weathered not just wind and sun but gradations of defeat that had turned the light off in their eyes.” Michelle McNamara’s I’ll Be Gone in the Dark is precise and atmospheric in chronicling the lives that the Golden State Killer interrupted. It’s also a layered story about obsession: the killer’s with his victims, and McNamara’s with tracking down the killer. Reading the book, one tends to get pulled in and obsessed oneself. A number one New York Times Best Seller, I’ll Be Gone in the Dark was a best book of the year from Entertainment Weekly, The Washington Post, and Esquire, among many others. On the occasion of its paperback release, I talked with Patton Oswalt about it at the Last Bookstore. I was ever-so-slightly starstruck, and he was generous and thoughtful and, even on this topic, funny.

¤

REBECCA SCHULTZ: What’s it been like seeing this book go out into the world?

PATTON OSWALT: It’s bittersweet. The book showcases what I always knew: that she’s a brilliant writer, and so it’s been gratifying to see the acclaim that the writing itself has received. It’s great to see who she’s inspired, too: the explosion of true crime podcasts; and, also, a lot of working homicide cops and detectives going, maybe some of these bloggers aren’t so kooky and bothersome as we thought, and actually using them as a resource. At the same time, at events like this there are always questions that I’m not equipped to answer. I’m not as intelligent and empathetic as she was. It’s like you’re sending out a rodeo clown to talk about someone who’s discovered cold fusion, and for some reason he’s the one who has to answer all the questions.

And then of course there’s the influence her work had on the investigation itself.

Right. One of the reasons that this guy got so much renewed attention was that she renamed him. It sounds awful to say but it’s branding. First, his name was the East Area Rapist, or E.A.R., and then a couple years later there was a reporter doing a story who misquoted a cop who said he’s like the original Night Stalker. So they added the O.N.S. So now he’s got a nickname that takes half an hour to explain, and it sounds like EAR-ONS. Like, wait, is he a Winnie-the-Pooh character? [Cold case investigator] Paul Holes was like, this sounds really creepy but: Zodiac, Night Stalker, Hillside Strangler. Great names. That focuses your attention. But EAR-ONS? When she gave him the name Golden State Killer he was like, thank God. That will help.

And Michelle knew that when she renamed him.

Definitely. I remember her trying to decide what she should name him. She had a whole list of possibilities. But she settled on Golden State Killer. It’s got the word killer in it but then golden state — there’s something eerie and poetic to that.

You mention her empathy. That’s such a powerful force in the book, the way she connects with investigators and victims.

Yes. Usually in true crime narratives you have this tormented, faceless killer, and his victimized targets, and the cops that close the case. But in this case the cops are often even more tormented than the victims, because they’re carrying the weight of, why can’t we bring order and sanity to this world. That takes a psychological toll on people, and she really nails that.

And she felt that toll, too. She writes so beautifully about going down the “rabbit hole” of the investigation.

It’s like falling in love with someone. Investigators talk about it in those terms: they say things like, I’m really liking this guy. This guy’s looking really good. And then you hit a wall that totally exonerates him. I think one of the reasons that the investigators she spoke to respected her is that she would bring them solid theories, that she’d really worked out, and when they shot holes in them — not to be mean to her, they were just like, let me just stop you, these two pieces of information negate everything that you’ve done — she would accept that, brush herself off and keep going. There were mornings when she’d be weeping, so frustrated, and then get right back to work.

One of her favorite true crime books was Robert Graysmith’s Zodiac. She read it over and over. Like I’ll Be Gone in the Dark, it’s a book about someone’s descent into a rabbit hole, but unlike Michelle, he isn’t aware that it’s happening. He’s not cognizant of what he’s revealing in his narrative.

Whereas Michelle is so self-aware. Was the hybrid genre that she’s working in — the way she uses memoir to incorporate her relationship to the investigation — built into the project from the start, or did she come upon that through the writing process?

It developed organically. There was a turning point for her when she was writing for her blog, “True Crime Diary,” about a couple shot on a beach in Jenner, California. If you look at the facts of the case, it looks like, a couple was camping on the beach and someone came out with a rifle and shot them. Okay. But Michelle went up to Jenner, and took a video camera with her down to the beach. It was a rocky beach, and it was difficult and dangerous to get down to. That totally changed the narrative for her. Walking the route that the killer would have taken, she realized that this was not a guy who just walked down to the beach. This was somebody who was very comfortable with the outdoors: he’d have to be, in order to get there, carrying a very heavy rifle, at night. Her experience actually gave her more insight into what a possible solution could be.

She also needed to be self-aware about her own experience and perspective because she knew that, whether they want to admit it or not, an investigator’s values and preconceived notions are the prism with which they look at a crime. I’ll Be Gone in the Dark is in a lot of ways a portrait of Northern California in the 1970s. There was a lot of misogyny, that of course did not feel like misogyny to the people thinking that way at the time. Michelle would look at police files and find notes about the promiscuity about some of the women who had been raped. Of course that affects how the crime was initially investigated.

Like the Janelle Cruz case, how they assumed that her killer had to have been one of the guys she’d dated.

Right. Those were the social norms of the time, which were of course butting up against the women’s liberation movement, the “me” generation, families fracturing all over the place. Some of these investigators might have felt they were standing on unsteady ground, and trying to look at a case, while their own lives were getting disrupted.

And maybe that’s some of what the killer was reacting to, too.

Yes. A friend of mine who read the book said, what’s really amazing is, these are people that are living in sunny California in the 1970s trying to build fun, happy lives. They should have been allowed to have fun, happy lives. That’s what life was all about back then. But there was somebody off in the shadows resenting this movement and warmth and sunshine. That’s really what it was, behind the murders and the rapes: this feeling of, I want to stain these lives somehow. Everything feels really sinister, after a while, when you read it. The way she describes the suburbs — nothing feels safe anymore.

That eeriness reminds me of this beautiful line, about why she wanted to pursue this investigation: “The unidentified murderer is always twisting a doorknob behind a door that never opens. His power evaporates the moment we know him. We learn his banal secrets.” I love the idea that he becomes”banal” when we can name him.

That was another thing she was always talking to me about. When I was in my early twenties, my friends and I were all really into serial killers. It was a safe way to seem like a dangerous badass, to know all the statistics and everything. She was like, that’s a phase that people go through in their twenties, then you get older and you realize that the reason that these people are murderers is because they’re the blandest zilches on the planet. They try to paint themselves as these cold antiheroes. They’re given names like the Green River Killer and it’s like, oh my God, this guy must be like a combination between Dracula and Big Foot. Then they catch him and he looks like Mr. Roper from Three’s Company, and it’s like, of course that’s the reason he’s killing people: because he doesn’t take up any space in the world.

That’s why I love the title of her epilogue: “Letter to an Old Man.”

An old man. Yeah. She’s saying, if you’re alive you’re an old, frail, slower man and that’s what you always saw yourself as anyway, and now you actually are. And he is. He’s a seventy-three-year-old ex-cop named Joseph diAngelo. At a book event in Sacramento I met a lot of his surviving victims — his rape victims. They said the book, and the capture, didn’t give them closure. What’s actually helping them is, every time there’s a court hearing, they go and sit in the front row and stare at him, and he can’t meet their gaze.