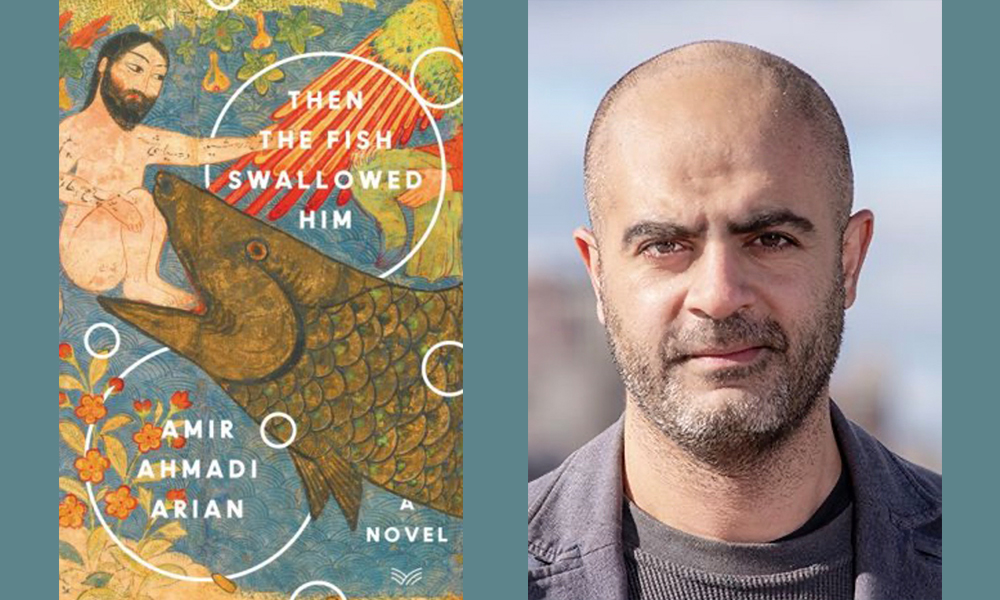

I remember a time that I was struck by an essay on Maurice Blanchot’s literary works, and as I read it I kept thinking how it felt like an indulgence. At the end I looked back to check the essay author’s name and for the first time I came across Amir Ahmadi Arian. It’s been 15 years since then and throughout these years Arian has written many more essays in both Farsi and English, as well as several novels, though most of them were banned in Iran, which eventually left him no choice but to leave the country. He currently lives in New York, where his debut in English Then the Fish Swallowed Him, has been published recently. Fish is a riveting story of Yunus, a bus driver whose political ignorance unsuspectingly confronts him with Iran’s political demons. It is a narrative of lacerating scrutiny and agonizing solitary confinement, through which Yunus’ sanity begins to erode.

What I liked about the novel was that even though it has been scaffolded on mythological tales like The Book of Johan and the biblical myth of Leviathan, it remains a perfectly contemporary story. Then the Fish Swallowed Him is a penetrating political fiction emerging at a time that this genre has been deprived of its principle traits in recent years and been overshadowed by blunt, flavorless dystopian novels that set no task but to tritely entertain readers. Arian’s novel reminds us once again that the novel is a dynamic human knowledge repository, not a numbing gel.

I talked with Arian about Then the Fish Swallowed Him, censorship, language and life in Iran, and now in America.

¤

ELHAM MOHAMMADNEJAD: Your novel has been compared to 1984 and other dystopian novels with political themes, which I’m sure is intriguing to readers. I would like to know how you feel about these comparisons?

AMIR AHMADI ARIAN: I’ve never thought of this book as dystopian fiction, simply because it reflects everyday reality in Iran. Some of my closest friends have gone through a similar process, only in a much more arduous and difficult fashion than what the character in this book undergoes. To me it was always a perfectly realistic novel. It comes down to the gap between daily experience of life in Iran and in the West, the fact that it’s painfully common in Iran to be arrested for nothing and thrown in solitary confinement and tortured and interrogated intensely and violently. I was just recording what I had seen in my whole adult life.

In most dystopian novels there are imaginary characters like Tinkpol in 1984 or those Mechanical Hounds in Fahrenheit 451. But in your book the interrogator is a human being, which makes the interactions way more real and complex and gives it a strong psychological dimension.

This book is also very well documented. I didn’t really make up that much, especially in the solitary confinement chapters. A lot of it is based on testimonies I gathered from people who spent time there. Sometimes their experiences, their struggles in there, are brought to the page without much change.

Why are your protagonists always named after a prophet? Like the last novel you published in Persian, The Absence of Daniel, and now Yunus (Jonah)? It looks like you have a thing for fable and allegory.

I do, especially for tales from scriptures and the stories of prophets. I really love Quran and the Bible as collections of stories. Millions of stories have been circulated for as long as humans lived on earth, but only a few have traveled across centuries to get to our times, and many of them are stories of prophets. It suggests that there is something about those stories, a compelling power that transcends religious doctrines, that enables them to touch a deep chord in human psyche. I love the process of reimagining the story of a prophet’s life for our times. Those ancient stories give you a sort of anchor, a solid ground, on which you can build your own story. I am a big fan of the novels that follow that path, such as E.L. Doctorow’s The Book of Daniel or Thomas Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers.

So why Yunus? He is not a prominent political activist, or really that much interesting as a person. He is a complete nobody. What did you want to accomplish with him that you couldn’t do with a political or human right activist?

It also comes from the fact that I was trying to write a realistic novel. So many of the people you hear their names and their news as political activists in Iran didn’t set out to be one. They were just ordinary people who participated in a protest, or a strike, just because they were mad and fed-up with everything, having no clear idea of the risk they were taking. They went along and took part in a protest and ended up in jail, and they actually became famous after they are arrested not before that. They make up a substantial proportion of political prisoners in Iran, and yet their stories have gone largely untold, which motivated me to create a fictional version of them.

I believe you could never have published this book in Iran. How did censorship affect you as a writer in Iran?

Censorship is the main reason I am writing in English. As recently as 10 years ago I had no desire to switch language. I was perfectly happy with writing in my native tongue. But two of my novels and one story collection were banned within a few years. Then the Green Movement came as the last straw. I was deeply involved in that, and when it failed, things took a dark turn. I lost my job as an editor in a publishing house, and then the newspaper where I was a columnist was shut down. Many in Iran think I started writing in English because I pursued global recognition but that was not the case at all. In Iran I was an established writer with a readership, writing in a language I loved. Switching your writing language in your 30s is an enormous risk. It almost borders on madness. I had to abandon everything I had accomplished, and it was so highly unlikely that I would get any of that as an English writer. I took that risk because for me life as a writer in Iran became impossible, and that was the only life I knew how to live.

How has been your experience of life in American society and New York in particular.

New York is a great city for variety of reasons that innumerable people have laid out in a thousand ways. What I really like about this city are the people I’ve met here. Folks from all over the world come through this city, some of the smartest minds on the planet, some of the most interesting people around. Some live here for a while or permanently, some stay a short while, and if you are out and about chances are you meet really incredible people quite frequently. That’s what I am grateful for the most.

You started as a journalist back in Iran and also a literary critic and published many essays and reviews, then started to write fiction. Talk a bit about that transition?

I did them all at the same time. It wasn’t like I was first a journalist and then began to write fiction. In the intellectual climate of Iran, those boundaries are quite blurred. When you are a writer, you are supposed to write everything. In the same week you might write a poem, then a column for a newspaper, then a short story, then you translate fiction or nonfiction, then the beginning of a long personal essay. For me, like many others, writing in all those genres and forms came at the same time.

This is your first novel in English. How has writing in English been different from writing in Persian? Do you describe it merely as a change facade, or have you experienced a more fundamental transformation?

Oh, it’s very fundamental. In a different language you are almost a different person. Language is the main way of perceiving the world and contributing to it for our species. When you live in a different language you inevitably become a different person. I don’t really compare writing in two different languages because I have a character split in half, and I don’t see much communication between those halves.

Having read your previous novel I notice that politics is always present. Here as main theme and in the last one more in the background. Can I ask why is that?

Because I grew up in Iran. You just cannot avoid politics if you grew up there.

Are you trying to build a body of work with connections among your novels?

Not really, but they come from the same life experience, the same upbringing. I really don’t know if I can ever avoid politics in my work. If you live in a society where state is so present in every nook and cranny of your everyday life, often in an intrusive, sometimes violent fashion, I don’t know if you can write a novel about that life that is not political. To me this sounds like a luxury I have never experienced.

Of course people care about politics and it’s reflected in their books, but when it comes to you it seems that you write political novels in the technical definition.

That is probably true. If you want to know what kind of novel you write, it’s a good idea to look back and see what were the novels that influenced you the most. In my case, so many all of those books are very political. The Latin American authors of the Boom generation, for instance. Mario Vargas Llosa in particular. Or War and Peace, or Balzac’s novels, which are far more political than people realize, or Dickens’ Bleak House. Also a lot of Middle Eastern novelists, Egyptians in particular, like Sonallah Ibrahim and Gamal El-Ghitani. The list goes on and on.

Besides that, I believe that there is a peculiar relationship between fiction and politics. I wrote about it once, on how fiction writers and politician are actually rivals, because both careers are basically predicated on making up believable lies, and both of them deploy language as their main tool. They are rivals because the lies they tell serve different, often diametrically opposed, purposes. Politicians make up stories to gain power and hold onto it, fiction writers make up stories to undermine and expose politician’s stories, or other stories that serve those stories, pretty much everything that our societies consider norm or natural. I think that explains why in a country like Iran fiction is censored so heavily even though it doesn’t have a big audience, or any tangible influence in the society.

Thank you for that, and the last question: what is one thing you can tell us about Yunus, which hasn’t been mentioned in the novel?

Well, he’ll be out of jail at the end of the book, but he is not going to live long after that.