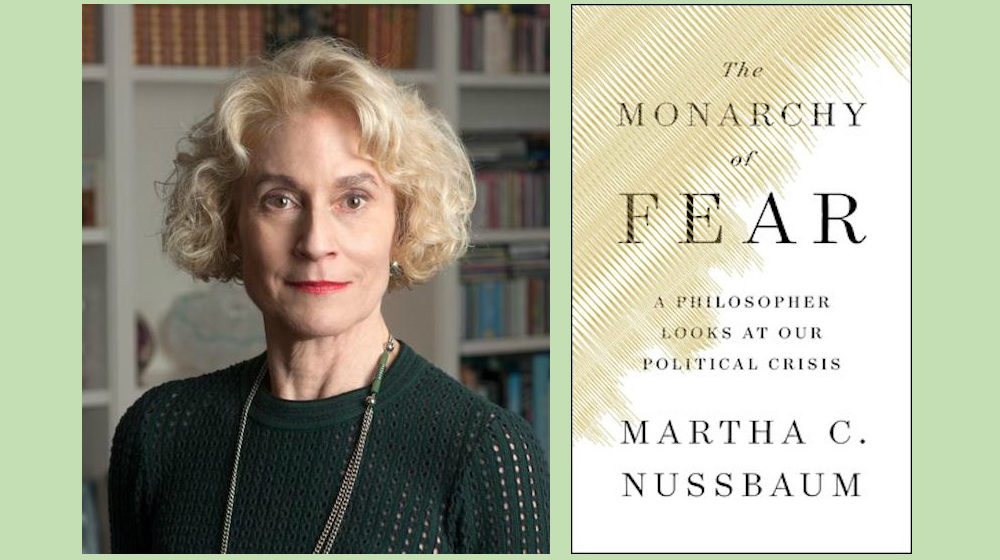

How might a fearful response to present-day political developments further isolate us, impeding prospects for collectively mobilizing towards a more constructive future? How might fear infest emotions such as anger, disgust, and envy, “so that it isn’t really possible to give a full account of any of them without thinking about them in relation to fear”? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Martha C. Nussbaum. This present conversation focuses on Nussbaum’s book The Monarchy of Fear. Nussbaum is the Ernst Freund Distinguished Service Professor of Law and Ethics (appointed in the Law School and Philosophy Department) at the University of Chicago. She has chaired the American Philosophical Association’s Committee on International Cooperation, the Committee on the Status of Women, and the Committee for Public Philosophy. Among Nussbaum’s recent awards are the Prince of Asturias Prize in the Social Sciences (2012), the American Philosophical Association’s Philip Quinn Prize (2015), the Kyoto Prize in Arts and Philosophy (2016), and the Don M. Randel Prize for Achievement in the Humanities from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (2018). Her recent books include Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach (2011), The New Religious Intolerance: Overcoming the Politics of Fear in an Anxious Age (2012), Philosophical Interventions: Book Reviews 1985-2011 (2012), Political Emotions: Why Love Matters for Justice (2013), Anger and Forgiveness: Resentment, Generosity, Justice (2016), and Aging Thoughtfully: Conversations about Retirement, Romance, Wrinkles, and Regret (co-authored with Saul Levmore, 2017).

¤

ANDY FITCH: Could we start with you in Kyoto as the 2016 US election results come in, contributing in your own way (The Monarchy of Fear suggests) to the “nebulous, multiform fear suffusing US society”? First, as an example to which readers might relate, what parts of your own initial response lacked balance or fair-mindedness? And given the odious nature of Donald Trump’s particular form of politics, when might fear make sense as a political response, and when / how / why do we nevertheless need to navigate our way beyond an immobilizing sense of fear?

MARTHA C. NUSSBAUM: I was alone in Kyoto, surrounded by people I had never met before, in a situation where I knew my job was to be gracious and express joy and gratitude for the award they were giving me. This combination of isolation and necessary cover-up made my fear much worse. And I recognized the imbalance in myself. As a mother I’ve had so many times when in the night I worry that my daughter won’t come home safe, and of course she is just fine and I have lost sleep for nothing. The same thing happens in other contexts (doctor’s appointments, for example). So I recognize my own tendency to jump to the worst possibility, and I know that this is misleading. In the case of the election, I know enough American history to know that we have survived much worse — even in my lifetime, with the McCarthy era, the lynchings and other violence of the Civil Rights movement. Gandhi thought fear was never appropriate, but that was because he thought strong human love was always inappropriate. He was like the ancient Stoics, as Richard Sorabji has shown in a brilliant book. I don’t go along with that. I think love of particular people, love of a country, love of good ideals and values, these are appropriate, and indeed at the heart of a good human life. But then fear is also appropriate when these things are threatened. However, fear has a tendency to gallop ahead of the evidence and paint the future in black. That is not useful, so we need to take a deep breath, to assess the threat, and to figure out what we are going to do about it.

And here, given your ongoing investigations into a variety of basic emotional structures, could you describe your decision with The Monarchy of Fear to depart from considering seemingly separate emotions in isolation from each other, and instead to present fear as a primary source for any number of potentially overlapping or divergent emotional states, such as anger, disgust, and envy? Again, which distinct aspects of fear and / or which contemporary social circumstances prompted that shift in approach?

It’s not exactly that fear is the source of these other emotions, it’s rather that it creeps into them like a poison and makes them more volatile and dangerous. Fear is probably the earliest human emotion developmentally and also the most primitive in evolutionary terms, shared with all vertebrates and many invertebrates. So it has a particular tendency to rush ahead of evidence, and what I realized before starting to write the book is that fear does infest the other emotions, so it isn’t really possible to give a full account of any of them without thinking about them in relation to fear. Anger has a tendency to irresponsible scapegoating that is fed by fear; disgust is all about aversion to the signs of our mortality and animality; envy is fueled by anxiety over the fact that some people have the good things of life and the envier doesn’t. If the envier felt that she could get those things by her own efforts, she wouldn’t need envy. So the envy arises because of a sense of impotence that is closely related to fear.

Again in terms of sketching fear’s diffusive reign, and perhaps also sketching this book’s basic emotional stakes, could we bring in a fear of death as shaping (unconsciously as much as consciously) our everyday lives? I found your account of the Rigoletto experience quite moving, in part because I love the music, but also because my own aunt asked me to watch Halloween with her 35 years ago, when I wasn’t ready, which set off years of anxious reflection on the fact that I (and everyone I love) already carry death inside me, which may reveal itself at any instant. Such fear of unshakeable, unanticipatable mortality seems a steady backgrounded presence in The Monarchy of Fear. Could we bring it briefly to the foreground? How has it driven your own philosophical reflection, personal experience, practical thinking?

The Roman philosopher Lucretius is a huge presence in this book, and he does advance the view that fear of death lies at the bottom of most human bad behavior, including hypercompetitive behavior and even wars. I think he is right about fear, but not entirely right that it all comes down to the fear of death. We are vulnerable in many ways that are to some extent independent of death. Immortal people like the Homeric gods can suffer horrible physical pain (all the worse if it never ends); they can suffer betrayal, loneliness, and loss. So I think we have many things to fear, and death is just one. But of course it is a huge one, and it becomes bigger as we age.

My Rigoletto experience was, like your Halloween experience, a sudden shock confrontation with death before it had even appeared on the horizon of life. At age six I had never known a family death (my grandmother lived to be 104, so I encountered my parents’ deaths before hers!). Verdi’s music conveyed the power of death so indelibly. But of course this opera was also about love, and giving up your life because of love. So yes and no: the fear of death is one source of reflection, but only one. I actually think the biggest sources of my reflection and my experience have been love and the possibility of loss. I’ve written most of my work out of experiences of love. And I’ll write more: I was just talking about this with my co-author and close friend Saul Levmore, and we might do another joint project (after our book on aging) about loss, risk, grieving.

In terms of universalizing claims for fear of mortality, when should we also parse something like an infantile state of material necessity (perhaps experienced as a traumatic lack of self-sufficiency) from any more abstracted self-questioning regarding one’s minuscule mortal place in the cosmos? Do we need, for example, a sense of soul-endowed individual agency (perhaps particularly strong in certain Judeo-Christian religious traditions) to fear the apparent loss that death brings? Or which parts of this fear of mortality (including more generalized human vulnerability) feel the most reactive, and which parts the most speculative — and how might those two strands manifest in personal behavior and in everyday social norms?

No doubt cultures vary about how they construct the fear of death, but I think people everywhere have all sorts of ways of consoling themselves about mortality. Some do like to think of how small we are in the vast universe, and that was one strand of the Western philosophical tradition (represented by Epicurus and Lucretius, among others). It is also a big part of Buddhism, which asks us to reject the very idea of the individual. Religions that teach posthumous judgment and punishment do give further reasons for fearing death, but they also give such amazing reasons for hope, which is a large part of their allure. Even atheist John Stuart Mill, in his essay “The Utility of Religion,” admits that religious hope has at least one good aspect: we can look forward to seeing our loved ones again (he wrote this shortly after his beloved Harriet had died). Mainly, I think that people fear death because, like Mill, they love other people and see these people cease to exist, and that is terrible. Whether or not they fear their own death, they have reason to hate death for the way it rips love apart. But there is a good aspect to this also: learning about loss connects us to all other human beings, and makes us realize that we are all in the same boat. For this reason Rousseau thought that his young pupil Émile ought to learn about death and vulnerability quite early, by experiencing the deaths of beloved animals, and that this would prevent him from becoming like the kings and nobles of France, who foolishly thought that they were above the common lot of human beings.

Well in terms of overcoming our inclinations both to denial and fear, I find particularly rousing your depictions of fear as asocial and often intensely narcissistic: as choking off outward-focused compassion, as stifling future-oriented prospects to collaborate on improving our collective well-being. Along such lines, could you sketch your concerns about present-day progressives claiming “unprecedented” injustices emerging out of this Trump administration? Could you outline some future costs we will pay if we indulge in ahistorical apocalyptic thinking today?

First of all, my students just don’t know much history. I’m teaching a little seminar on the McCarthy era and the artists and writers who were blacklisted, so that the group (all law students) can learn that there was an era in which the academy, the arts, the media, were all gutted by a vicious demagogue. Nothing like that is on the table right now, though of course we should always be vigilant. Again with immigration: when we discuss this topic in my course on Global Inequality (which I co-teach with an economist), we have students read, first, a history of US immigration policy, in order to see how racist it was from its inception, and how today, with all the problems we undoubtedly have, the standards for legal immigration are a good deal less racist than they used to be. Perspective is crucial to really useful vigilance, but if you don’t know any history it is difficult to have perspective.

Cultivating perspective here makes me think of how The Monarchy of Fear borrows from D.W. Winnicott’s notion of a “holding environment,” a relational context providing a good enough (with perfection not necessary) means for addressing an individual’s fundamental material / emotional needs — again as emerging out of infantile experience and extending throughout one’s life. If we assume that individuals cannot develop and keep refining capacities for reciprocity, love, or reflective deliberation without first securing this type of sustaining context, could you give some concrete examples of where you see present-day American society doing its best and worst job of fostering both a secure economic / material and relational / cultural environment for its citizens?

Winnicott talked a lot about holding, but the phrase I especially borrow from him is the “facilitating environment.” That’s a more active concept, which suggests that in the family and, similarly, in society, we should not be passive, but should actively create structures that facilitate concern and reciprocity, and that inhibit narcissism. There are so many sites where this either happens or doesn’t, and good choices tend to be contextual, so let me just focus on Chicago. Two outstandingly good things, I think, in the recent period, have been the decision to make community college free for all, and the decision to lengthen the school day by adding arts programming (Rahm Emanuel, a former ballet dancer, worked this out in consultation with artists including Renee Fleming and Yo-Yo Ma). But there are some worsts in Chicago too: the failure to root out corruption that saps the accountability of city government (as the revelations about Alderman Ed Burke are showing now), and the difficulties in reforming the police department.

The notorious case of Laquan McDonald is just one of hundreds, and they send a message that no black male is safe in Chicago. I think that the current police chief is starting to turn things around, and that there is slow movement in the direction of accountability. I greatly admire Lori Lightfoot’s work as head of the Chicago Police Accountability Task Force. I voted for her for mayor and was surprised and extremely heartened that she was the top vote-getter and now appears to be leading going forward to the runoff — despite the fact that she is relatively unknown and not backed by big money. It is a very good sign for our city. Another good thing of a very different sort has been the tremendous surge of involvement in the midterm election campaigns in this city, showing a level of hope and concern that were both impressive and effective.

Since you’ve mentioned both arts programming and active citizen initiatives, and here again in Winnicott’s own terms, what could ongoing imaginative play in Americans’ adult lives look like, as one means of forever continuing to reassemble, recalibrate, and re-fortify a facilitating environment — and one means of fending off any fear-prone stasis from entrenching itself?

Winnicott thought that the arts have an essential role in democratic society for precisely this reason. As participants or spectators in theatrical, musical, and dance performances, as lovers of literature, or as lovers of fine art and sculpture, we do engage in imaginative play and nourish our own imaginative capacities. We can also do that in personal relationships, through humor and reciprocal expressions of emotion. I have a former student, Jeff Israel, who has just finished a brilliant book that Columbia University Press will shortly publish, about play and the role of public humor in dealing with fraught emotions in a democracy. He takes Jewish humor in the US as his specific example, focusing on Lenny Bruce, who invited his audiences to play in a very productive way, which took the sting out of their divisions.

As one other test case for post-infantile facilitating environments, The Monarchy of Fear also notes an increasing intellectual fragility on college campuses. To what extent do professional educators need to view this trend less as a lamentable external development (“Kids these days…”), and more as a symptom of our own institutional failings to create the types of social contexts that best prepare students for a robust intellectual engagement pushing beyond anxious, tepid, and / or mutually accusatory (all fearful, perhaps, in different ways) reluctance to constructive civic participation?

That’s a very good question. I think this points to the dark side of a positive development, namely early education, both in the home and in elementary schools, that puts bullying off-limits and encourages young children to feel safe. That is good up to a point, and we should always repudiate incivility and contempt in the classroom. But people then confuse the idea that they should not be subjected to personal insults with the very different idea that they should not be exposed to uncomfortable ideas. It’s not so easy to make this distinction, so it’s not a dumb mistake. But we must continue to insist on it, and on discussing a very wide range of views. For this reason I gave a portion of my Berggruen Prize to our law school to underwrite a program in which students sign up for lunch seminars on difficult and controversial topics with two faculty members who hold contrasting views. So far, the program (which existed before my gift) has been remarkably successful in getting (law) students to discuss such difficult topics as the bakery cases, and transgender bathroom cases, in an atmosphere of civility and mutual respect.

Again, your book describes envy as the wrong response “even when its cause is just”: since envy can slide insidiously from transparent desiring (“I want what they have”) to self-deceptive moralizing (“They must not deserve what they have, and must have done something wrong to attain it”), since envy presumes a mistaken zero-sum mindset in which one only could acquire happiness by taking it from somebody else, and since envy calls forth an impulse to tear down existing social arrangements (rather than to stitch some more compassionate arrangement together). Here could you describe how proactively making the case for expanded individual rights (perhaps along the lines of F.D.R.’s Second Bill of Rights) might allow a democracy most effectively to combat these corrosive consequences of social disparities and social envy — since, as you suggest, nobody can envy what everybody already has?

Yes, envy gets out of hand when people feel a sense of impotence and despair about attaining what the fortunate have. So one way to diminish envy’s hold is to focus social attention on things that all can attain. A high school is a veritable crucible of envy, especially when all focus is on athletic ability or physical desirability, things that many people feel they can never attain. A school culture is much healthier if there are many different expressive outlets, and if emphasis is put on things like effort and good citizenship, which all can attain.

Similarly, in society, one part of the task is to shift emphasis from big cars and fancy clothes to more enduring attributes. But another extremely important and eminently doable thing is to bring key competitive goods under the aegis of protected rights. When all have Social Security, health care, and access to a college education, these can’t be objects of envy. For this reason I see very little envy in the Nordic countries; indeed people are often positively ashamed of having things that other people don’t have.

Conversely, in our own society, generalized appeals to envy often carry quite specific calls for retribution. And perhaps we can in the abstract recognize retributive impulses as an indulgence in “irrational magical thinking.” Perhaps we can commit, while reading your book, to harnessing and channeling “transformative” anger in the way that successful parents might — refraining from punitive responses, instead establishing a more constructive context encouraging better behavior. But at present, it can seem difficult even to arrive at a clarified consensus on what “retribution” itself looks like. Amid fraught status competitions (which do appear inherently zero-sum, in which one person’s or group’s privilege does depend upon another’s deprivation), what to do when what feels like expanded equality to one party feels like retributive vengeance to a second party? Or for a more concrete question: which aspects of populist political agendas from both right and left at present might we consider rational efforts at promoting fairness and justice, and which might we consider irrational envious retribution?

First we need to create spaces to sit down and have a real debate about these things, a debate conducted with civility and respect, and with lots of facts (scientific, historical, and cross-cultural). I think this has been happening slowly with universal health care. When I was a teenager people hated the very idea, but by now many Americans can see how outrageous it is for a person to be denied coverage on account of a preexisting condition. “Obamacare” has become much more popular now that Americans experience it. So now options like Medicare for all are really mainstream, alongside more moderate proposals including a “public option” within an insurance scheme. The upcoming campaign will be very useful in sorting these things out.

Another issue where we’ve made progress is mass incarceration. Most people now see that system as a failure and want something different. And the debate over drugs has also shifted in a useful way, from a phobic reaction to all drugs (apart from the ever-popular alcohol), to a tolerant regime for marijuana — and with real worries now focused where they belong, on both legal and illegal opiates. Even though our public culture is shrill and in many ways flawed, it’s encouraging how consensus has evolved on these issues.

In terms of your own impressive record of ambitious civic initiatives, I find especially insightful your description of one of the trickiest enterprises in politics: how to push persistently for a sufficient solution to an intractable-seeming social problem, without giving in to frustration, fatigue, or wishful thinking as you keep encountering both predictable opposition and unexpected snags. And here I especially appreciate your appeal to the sustaining powers of love as a motivational force. Could you describe the conception of love that you have developed through reflection on the precedents of Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Nelson Mandela each cultivating a love for humankind premised on goodwill, on hope, on a realizable sense of justice — more than on personally liking every specific individual met along the way?

You are much too kind speaking of civic initiatives. I write about such things, but outside of the university have done only things like working for a political candidate. To answer your question, though: King was very clear in his writings that he did not mean romantic love, nor did he mean friendly love. He meant something like Christian agape, a general good will to all. That is a little different from the love I defend in Political Emotions. I argue there that if love is to motivate real people it will have to make contact with the deep early sources of attachment and emotion in our lives, which are more particularistic and, in a way, erotic. This can be done through poetry and the arts, and I give many examples in that book. I actually think that King’s rhetoric is more romantic than his theory allows: his prose is soaringly poetic, and he summons people to love of the “curvaceous slopes of California,” the “heightening Alleghenies of Pittsburgh,” in a way that goes beyond mere good will. Quasi-erotic emotion is slippery, and needs to be directed by good political principles. But in connection with those it is an essential and powerful source for change.

Sure in terms of constructively harnessing that slippery quasi-erotic potential, even those lines from King you just quoted make me think of Freud comparing a mountain range’s soothing contours to the maternal body we may have seen lying beside us as babies. And again in terms of how embodied affect might prompt conceptual parsings and corresponding social expectations, I particularly appreciate The Monarchy of Fear’s distinction between sexism as a set of dubious beliefs about female inferiority, and misogyny as a set of concrete behaviors intended to reinforce male gender privilege. I appreciate your sketch of a historical trajectory on which would-be sexists (particularly men of your generation, when finding themselves outperformed by women in competitions for jobs and resources and prestige) can’t even take comfort in delusions of superiority anymore, and instead need to double down on misogynistic tactics. So how would you most constructively coax such misogynists away from projecting their own palpably embodied (though perhaps unacknowledged) fears onto “horrible women” (in our current president’s phrasing), instead towards addressing these fears by engaging questions we all need to face about what love, care, and family life might look like in an era of increasing female work and achievement?

First of all, let’s give credit to philosopher Kate Manne, from whose book Down, Girl I draw that distinction between sexism and misogyny — though the rest of my analysis takes a somewhat different course. As to addressing the social problems: I think a good social “solution” has three parts: the family, the workplace, and government and law. The family is where all children learn their ideas of gender, and ideas learned early tend to stick. So parents need to be vigilant and engaged in shaping the ideas of both female and male children about gender, since the peer culture may develop in a different direction. Workplaces can promote norms of equal respect in many ways, but one way is to give both men and women adequate family leave, and to dignify those who use it (rather than relegating them to second-tier status, as has so long happened in large law firms). And of course government has a large role to play in enforcing laws against sexual violence and sexual harassment, in being vigilant about subtle forms of workplace discrimination. We’ve come a long way, but there is further work to be done.

In terms of future-oriented concerns, The Monarchy of Fear also calls on the US to launch a national-service program modeled on Germany’s former national-service requirement, but recalibrated to address the contemporary American problem of citizens engaging so rarely across race, class, and regional lines. You describe this national-service possibility not receiving enough public attention right now, but I’ve actually talked to close to a dozen prominent political and intellectual leaders over the past year calling for such a program. And here I find particularly useful your call less for a moralizing than an entrepreneurial approach to creating a critical mass of support for such a program. Though I still note a frequent tendency in most national-service agendas to require somebody else (typically somebody young) to do the service. I understand why society might benefit the most by exposing young people to the broadest range of experience. But frankly, as many baby boomers retire, often from a diverse work environment to a much more insular domestic life, I wonder whether they couldn’t use such a service stint as much as any awkward iPhone-addicted teenager. So in terms of entrepreneurially selling rather than bureaucratically imposing national service, what about boomers starting with themselves as the service-providers? Or what about religious institutions pledging to fund a set number of such service contributions by retirees each year? Or what about national campaigns to incentivize prominent corporations to pledge such contributions from a set number of seasoned employees? Why don’t we first work on providing appealing national-service role models from the adult world, rather than trying to coax inevitably self-involved youths to reflect back to us our own values and commitments?

I think we should do all of these things. A governmental youth service program is valuable because it imposes similar requirements on everyone. But many professions are already doing what you recommend. Most large law firms handle a significant number of pro bono cases. For example, I recently held a seminar for one New York firm in which the young associates were working on the litigation surrounding the lead poisoning in Flint, Michigan. And most of my former law students who work for firms choose firms in part for the pro bono work they will have an opportunity to do. And what you say about people who do service work when they retire is also happening all over the place. However, because I oppose compulsory retirement (Levmore and I debate this issue in our book Aging Thoughtfully), I also think that people who retire should have the opportunity to seek another paying job, so we should not simply assume that retirees are sources of free labor! As for the reason for my focus on young people: our young people are extremely ignorant, most of the time, of other places, races, and classes, since housing in most of our society is strongly de facto segregated by race and class. They are therefore ill-equipped to be voters. So it’s important to strike early in giving them a broader education, before they become caught up in making money and supporting a family.

Pivoting then to broader professional contexts for your own work, I likewise appreciate The Monarchy of Fear’s account of today’s tenured philosophical ecosystem as often too constrictive for reinvigorating the ancient Greek / Roman philosophical enterprise of struggling to achieve flourishing lives for all, in always troubled times. I appreciate your account of why democratic decision-making especially demands transparent deliberation, constructive conversation, as well as carefully calibrated critique and dissent. And I do appreciate how Plato’s Socrates embodies in exemplary fashion such dialogic practice. I also recall though, say in the Republic’s ship-of-state analogy, Socrates’s quite daunting critique of democracy as a system of governance. So how do you see Socratic practice (even as Socrates articulates that damning critique) contributing to a robust democratic practice? Or how to parse Socrates’s dismissal of democratic institutions from his simultaneous advocacy for sometimes quieting our own voices, listening as attentively as possible, participating in the collective project of getting the argument right?

You are conflating the character Socrates in Plato’s Republic with the historical Socrates, for whose life and thought we have evidence of many kinds — including, most scholars believe, some Platonic evidence (from the Apology and Crito, for example, but definitely not from the Republic). It is clear that the historical Socrates was not taken to be hostile to democracy, since he incurred no disabilities when the democracy was restored after the oligarchy. Socrates did think that the direct democracy of the Athenians, where all offices except that of general were filled by lottery, needed a role for expertise, but that is taken for granted in modern democracies. What the historical Socrates called for was a more wakeful and responsible democracy, in which people practice self-examination and critical argument, learning how to get clear about what they and others believe, and how to conduct a respectful dialogue. In the Apology he says that he is like a “gadfly” on the back of the democracy, which he describes as a “noble but sluggish horse”: the sting of critical argument wakes democracy up, so that it can do its business in a worthy way.