Which harshest social conversations might call for which softest artistic media? Which of us might most often characterize ourselves as “hopefully invisible”? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Julio César Morales. Through a range of performance and visual strategies, both as an artist and curator, Morales explores issues around migration, underground economies, and labor — on personal and global scales. In one series of watercolors, Morales might diagram some of our present moment’s most inventive and most precarious means of human trafficking. In other projects, Morales might prompt new modes of interpersonal engagement and political reflection by employing the DJ turntable, neon signs, the historical reenactment of a famous meal, the social conventions of an artist-run gallery space. Morales’s artwork has been shown at Lyon Biennale, Istanbul Biennale, Los Angeles County Art Museum, Singapore Biennale, Frankfurter Kunstverein, Rooseum Museum of Art (Malmo, Sweden), SFMOMA, and The UCLA Hammer Museum, among other institutions. He is represented by Gallery Wendi Norris, and is curator of visual arts at Arizona State University Art Museum.

¤

ANDY FITCH: For Feast, you’ve mentioned your desire “not to translate the taste of food but rather the experience of eating.” Here could you describe how something like this “experience of eating” might operate across your diverse range of work? Could you discuss, for example, how enactments of eating might correspond to your interest in tracing complex, multi-directional intercultural exchanges? How might the ingestion of food provide a portal for nourishment and for infiltration / smuggling and for hegemonic consumption — all at the same time? How might consulting a native-foods anthropologist (though not always remaining faithful to the authentic or the local or the historical) for your public meal preparations make cooking more of a site-based, or even a landscape art? And in what ways does being the guest at a meal resemble being an individual (or species) in a broader physical or cultural ecosystem?

JULIO CÉSAR MORALES: Maybe I can first describe an upcoming project that will be a temporary public-art project. My food collaborator Max La Rivière-Hedrick and I will work in Los Angeles at a location which basically borders Thai Town, Armenia Town, and Mayan Town. We’ll work with one restaurant’s chef from each of these locations. We’ve asked them to develop a meal they had to leave behind when migrating to Los Angeles.

The site for this project once held an olive and citrus grove, before it became famous for the Hollyhock House and the Municipal Gallery. And even earlier, I think the Nestor Film Company had based itself there. So all of that triggered a memory of Carlos Fuentes’s 1993 book The Orange Tree, which traces the history of the orange coming to the Americas — across five short stories taking place in different eras. Our project will cue off those stories, and also cue off the immigrant stories of chefs who now own restaurants in the adjoining neighborhoods.

Making a meal you have left behind perhaps starts with what ingredients you can’t find in Los Angeles. So this “experience of eating” for us contains memory, specifically tied into homeland. Sometimes you just can’t re-create a meal in that precise sense, but hopefully the project can take these chefs, and the audiences they attract, back to certain childhood memories, from before entering the United States. I myself immigrated from Tijuana. I have these same kinds of complex memories: the experience of eating spicy Chinese food, and the scent of agave coming from my uncle drinking a tequila with his Asian dinner. So that hybridity of cultures, especially in borderlands (many Chinese fled to Latin America after the Chinese Exclusion Act), really left an impact on how I approach food and a reimagining of history through the senses.

Perhaps we do want to re-create or imagine a more historical California landscape. But we also want to explore what California might feel like 50 years from now. For example, if a dish uses lots of almonds, and since almonds use a lot of water (one gallon per almond), we’ll ask our chefs to make adjustments. We’ll factor in predictions about California’s agriculture 50 years from today. We’ll ask questions like: what about California will endure? What have we already lost? What substitutes can we make? A food anthropologist and a couple of scientists will help with that aspect of the project.

Also, for me, eating always has meant a daily event that happens at the table with family. With my family, here in Arizona, we cook from scratch for an hour and a half almost every day. We also sit down and eat and discuss everything going on in our lives. So, for me, food and the act of eating still offers that chance to keep your feet grounded in your culture but also within your family.

You also have mentioned “utilizing food as a conduit, translator, mediator, and negotiator,” and here could we follow up on that negotiating aspect? You and Max might seek to saturate the senses of your guests — but not to prompt a relaxed mode of passive consumption, so much, you say, as “to challenge and teach.” You even mention sometimes hiding this challenge from guests. So could you talk about cooking / hosting as sometimes a didactic art, sometimes a clandestine art, sometimes a narrative art not just of taste and smell and touch but of “timing and storytelling”?

Correct, this goes back to an emphasis on a “set-up situation.” Sequencing is very important. Maybe you set up an ambient live soundtrack for guests to hear as they enter. Maybe you serve a distinct drink as a precursor to an event. Maybe you spray a specialty-made fragrance between the dinner’s courses. This all comes together to disarm guests in one sense, to help them enter the moment and suspend life, and to embrace these carefully constructed experiences (which we call performances).

When I thought of creating this project, the only person I could picture working with was Max. Both Max and I attended the San Francisco Art Institute in the mid-1990s. I was trained as a video / performance artist, and Max in sculpture. Both of these artistic practices informed ways of working on these food projects, and setting up experiences for audiences as performative installations. When we graduated, I went into the studio, and Max went into the “kitchen” and started working at some of the best restaurants in San Francisco. We had shared a love and deep interest in art and food and history. With all of our projects about experiencing taste, we attempt to show audiences how they are not only eating, but also consuming, history.

From our first project together, Interrupted Passage, we learned so much by researching General Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo (the governor of Alta California, and a pivotal figure for California transitioning from a Mexican territory to a US state), and by reading his autobiography (housed at UC Berkeley). Vallejo was not happy with Mexico, and had his own future vision of what California should be: from his “open” immigration policy, to the first winery in California, to his lust for food. A former military man, and a cultured man, Vallejo actually hosted the invading Texas Militia. In the first confrontation, he said: “Wait. Why don’t you come into my house?” He lived in a beautiful 19th-century Victorian house in Sonoma, and the first thing General Vallejo did was offer them brandy/aguardiente mixed with black tea. Then he basically ended up negotiating his own future, connected to a “new” California, over an exquisite eight-hour meal (and without any bloodshed). This moment especially resonates with me, as an opposite to our current cultural climate, and to our current implausible president and administration. I love that strategy of mediation, negotiation, and persuasion.

So again, I imagine General Vallejo as this very forward-thinking person. He lets himself get arrested, rather than launching immediate battle. As he tells in his autobiography, he is taken from his home to someplace halfway between Sonoma and Sacramento, and housed with the Texas Militia (who do not know that Vallejo’s men have tailed them). Later in the evening a couple of Vallejo’s men dress up as women and get into the house. They find him and ask: “Do you want us to kill everybody right now?” And he says: “No, I want to go to Sacramento and negotiate.”

I love the narratives that Interrupted Passage’s various components provide about General Vallejo, presenting him both as host and hostage, both as devourer and as devoured, at this sacramental Last and/or First Supper. And chefs might have more artistic and cultural cache at present, but does it make sense here to think of General Vallejo (maybe also of yourself) as more of an innovative restaurateur, or a shrewd maître d’, or a lively party planner (operating alongside the masterful chef)? Or could you talk about other ways in which Interrupted Passage might playfully rewrite, for example, gendered presentations of history, with the camera focusing more on surface textures (the weave of jackets, the sheen of skin) for these military men, while leaving the incisive cuttings and trimmings and getting things cooking to the kitchen crew — as if that’s where the real drama takes place?

Interrupted Passage became a series of food performances (re-creating Vallejo’s eight-hour feast) and a video re-enactment we shot in General Vallejo’s home. The food performances began with a small group of participants, then grew from 50 to 350. The final performance was in Mexico City for the Museo Tamayo, where we created a menu considering what Alta California and especially its cuisine might look like if Vallejo hadn’t given up. We saw this as perhaps a welcoming dinner to the capital, for a hero who had fended off the gringos. The dinner for that event leaned more towards a French style — though Vallejo, who had very sophisticated tastes, also would have ingredients brought over from Spain, Asia, and Mexico. He actually had a Chinese chef, which added to the hybrid meals Vallejo was creating.

So the food cooked in his mid-1800s home kind of prophecies what we think of as contemporary California cuisine: farm-to-table, using smart ingredients, giving rustic recipes a little twist. Again, General Vallejo’s autobiography describes his love for food but also for culture — and, as you mentioned, for entertainment (or maybe the word “hosting” does make more sense). The descriptions he wrote regarding “hosting” influenced the way this video was shot. There is no dialogue, only sound, texture, and movement. My only direction to the cast was to arrive at the video shoot hungover.

A special feast was prepared for the video shoot, and the ingredients we chose were almost repugnant to the hungover actors. Specific scents can make you nauseated, and that is what I wanted to get from their facial gestures in the video. The Texas Militia had never tasted these flavors, and I wanted to capture that oddness and sense of discrepancy. Later on, our projects played with audience expectations — for example by editing out utensils, so that you might have to use a small hammer instead of more familiar utensils to actually break open the food.

The brick with chicken feathers, right?

Exactly, that was for La Alquimia de los Sueños (The Alchemy of Dreams), a multi-sensory performance inspired by recipes from the Surrealist women artists Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington. Some of these recipes allude to erotic dreams or create alternate dimensions. Each of our performance projects calls for its own distinct research, process, and immersive environment.

Well maybe bricks and food can come together here. We’ve talked a decent amount about eating, but your Interrupted Passage title also hints more concretely at mouths and intestines and even wombs. And tunnels of course could take us there, tracing not only what we absorb but what we release: and not just in terms of waste or ejection or escape, but also of birth or smuggling or welcoming or return. So here could you describe growing up in both Tijuana and San Ysidro, developing a “unique understanding of identity in relation to site and how one adapts to performance out of necessity,” projecting such performances in multiple directions, to multiple communities, all at once — and how artistic work around tunnels might help to situate you and your audience on both sides of the periscope or the binoculars or the magnifying glass or the mirror?

First of all, thank you for pulling these past quotes that put me on the spot! I like these connections. General Vallejo himself, in his autobiography, actually came up with the “interrupted passage” phrase. He talks about site-specificity, and taking hold of your own future. Vallejo considered it an “interrupted passage” when the Texas Militia came — which also meant a new opportunity to form what he thought California should become (not what the Mexican government thought it was or should continue to be).

I find a connection with Vallejo in my own upbringing — as someone not satisfied just being from one side or the other, but embracing a multiplicity of identities in order to be fluid, and at the same time balancing vulnerability with power.

When I think about my adolescent experiences in Tijuana, my cousins and I would spend the summers with our grandparents, and always had a blast (though I’m not sure how we all survived!). We also had this crazy uncle, Jose Luis, my godfather actually (as I already mentioned, my work is always somehow about my complex family), who would take us to wrestling matches (Lucha Libre) in exchange for digging a tunnel beneath his house. I still remember the scent of being underground, the cold and the dankness of that tunnel. My godfather never explained why we would dig this tunnel, other than to get to the “next street without being seen.” He’d just tell us to go in a certain direction. But my grandparents lived one block from the actual border fence.

Tunnels played this role of urban myth throughout my childhood, until authorities actually started finding tunnels in the early 2000s — a series of what were called “Narquitectos,” where the cartels had started to hire architects and engineers to build them. Tunnels are an important part of informal economies, and the smuggling of contraband or people. Some can be very sophisticated, with AC and a rail system. Or others are a pared-down version, with just wooden support beams and lights running off generators.

I ended up creating a body of work entitled Narquitectos, collaborating with a retired architect whose specialty was hand-drawn architectural images. It was important to draw these works on paper to scale.

When you look at one of these images, its top half is the originating tunnel from Tijuana, and its bottom half is the ending tunnel in San Diego. I got these images from the Border Patrol and INS websites. The majority of work I do in relation to the border comes from found imagery off the Internet. I still work with tunnels, whether conceptual or physical, in various ways.

And with the scent and dankness of those childhood tunnels still in mind, I again appreciate how your environmental and intercultural and interpersonal engagements don’t allow for the detached self-positioning celebrated by certain “landscape” traditions, but instead depict artists and observers and characters and audiences all as active (and ever vulnerable) parts of that landscape. Here I especially appreciate how your work creates cultural space in which to present the subjective perspective of the border-crosser, of the smuggled person — as a vital part of how this boundary-transcending ecosystem both observes and reflects on itself. I sense that polarized political debates particularly in the US at present tend to downplay this subjective, self-reflective presence of today’s border-crossers: instead offering paranoid accounts of “criminals,” or patronizing accounts of victims, and in either case not providing much room for the types of inventive agency and meditative depth that your work showcases. So could we pivot to the We Are the Dead video sequence? Could we start with Part One foregrounding an austere, scraggly American Southwest landscape, but soon superimposing kinetic constructivist designs and a densely syncopated soundtrack? Could we get to how this overall sequence begins as something of an elegy for those who have succumbed to cruel immigration-enforcement policies, but soon starts articulating a living or haunting or lyric presence — with I think the only actual verbal lines I’ve encountered in your videos? Why did somebody speaking right then seem essential?

I’ll give a bit of background on those videos. In the mid-1990s, while still a student, I learned about two brothers who crossed over into Arizona. They got lost, and decided to split up. In this intense heat, one of them made it to a Circle K shop, and the other was found dead with an empty bottle of tequila. The tequila was supposed to be a present for a family member in Tucson. But they had run out of water. And that story had always stuck in my mind. I even had dreams or nightmares about being the dying brother. I would wonder: What is your last memory, in that unforgiving hot desert, as you drink and hallucinate until your death?

Then a couple years ago, when I first moved to Phoenix, my father-in-law invited me to go hunting for javelina in February. I soon realized our path would take us right past where these brothers supposedly split up. So this idea of performance again came in, and I said “Sure, I’ll go hunting with you,” and brought my two-and-a-quarter camera and a whole bunch of film [Laughter].

So I walked around with a nine-millimeter gun, and a two-and-a-quarter camera on my neck, waking at four in the morning, covering 10 miles each day. So that project really marked me first coming to Arizona. And a lot of projects I do have real-life tragic elements, but also these ongoing mythic components and these set-ups of different sorts. So the We Are the Dead pieces, for example, don’t offer much video within the videos. They have animations and photographic still images. Those color bars and geographic shapes you see floating around come from GPS coordinates, but also from physical objects I found on the desert floor and sampled for their colors — shoes, socks, underwear, T-shirts, and other material.

I see this as “cultural sampling.” There’s the whole Tijuana aspect of inscribing new meanings to objects — like when you see Bart Simpson as a piggybank, that has a different meaning in Mexico than in the United States. By inscribing new meanings that way, I felt I could both belong on this hunting trip, and at the same time document this tragic location and create this mythic story or project. I have always been drawn to storytelling, mostly influenced by the great stories of my Grandfather Daniel and his adventures in Tijuana.

For all of those reasons, and because I wanted a harsh edge for this We Are the Dead story, poetics sounded like a great way to tell the story. So I asked a friend from Mexico City, the artist Miguel Calderón: “Can you put yourself into the mind of the dying brother in the desert? Can you describe those last five minutes, flashing through your life?” And so Miguel wrote this beautiful (almost humorous) poetic text that runs through Part One while you see the animation, the landscape, and then you see this poetry running through it.

For Part Two, I contacted another friend last year, Moises Medina, a historian specializing in American and Mexican history. I called him and asked: “Hey, can you can drink a bottle of tequila in one sitting?” He had to think about it for a minute, but he eventually responded: “Yeah, yeah, I can do that.” So again, I set up some parameters, and said: “Okay, I’ll give you one line.” And from that one line, he drank the bottle of tequila while coming up with Part Two’s story of the surviving brother. It all came from this opening line I made up: “Since my brother is gone, I no longer speak Spanish.” Tequila helped bring out all these emotions in this story about the brothers discussing their relationship, why they fled to the US, how they separated and how the survivor was coping with the loss of his brother. Moises embodied the lost brother and created a “broken narrative” as key words that surround the video.

Yeah I love how, as you say, there might be no video within the videos, but they still somehow stitch together a compelling story. Part Two offers an intricate structure of delicately threaded sections — just as its gridded, abstracted, exponentially reduplicated human figure starts evoking for me Andy Warhol’s stitched photographic negatives (themselves re-braiding together impersonal industrial reproduction and handmade human time).

Well when you mentioned people crossing over, that got me thinking about something like Land Art — but also just about people passing through and changing the landscape, leaving behind 300 backpacks on a ridge. When you look at the history of Land Art, you see Robert Smithson and Richard Long and those manly men cutting open the land, assembling it differently. But we also can find these other migrations and forced migrants altering the landscape with their own bodies.

Soundscapes also of course get stitched together amid your videos’ allover environments, with it maybe making most sense to talk about soundscape in relation to Subterranean Homesick Cumbia Remix, which focuses on an accordion: first hung above a riverbed, reflected in ripples, then sinking crocodile-like, then looking so matchy-matchy dragged along a beach. Could you describe what sound and what music do allow you to smuggle into these primarily wordless videos, and maybe how sound for your videos plays a role equivalent to scent in food-based projects — permeating your audience by crossing or dissolving or reshaping particularly porous thresholds of atmosphere, of mood, of individual and group and ecosystemic identity?

For that video’s soundtrack, I collaborated with Eamon Ore-Giron. We have this collective called Los Jaichackers, which basically focuses on hybrid culture and music from the Americas. That specific piece looks at cumbia music’s origins, coming out of German accordions, with part of a mid-1800s shipwreck ending up on an island of former slaves. They integrated this “strange-looking beast” alongside their African rhythms. And before long, every country from the region began to develop this flavor of Colombian “cumbia” music.

Originally, we did this project for the Prospect.3 triennial in New Orleans. We thought of two of the world’s largest rivers, the Amazon and the Mississippi, tracing these new paths for music. And where the Mississippi meets the Gulf of Mexico, you reach New Orleans, and you get Zydeco music. Or this past summer I had a show in a Berlin gallery, where I brought cumbia back to Germany, because they still don’t know that cumbia really began with them.

More generally for these videos, I usually try to do the music myself, or to collaborate with other musicians. I’ll also sample sound from the region where I’m shooting, basically with field recordings altered and integrating musical elements. I love to work with cumbia music and electronic music. Working as part of Los Jaichackers really pushes my video process in both shooting and editing. Eamon is an amazing composer who always adds surprising elements of tension and ambience with his sound work.

Silence itself stands out as its own moody soundscape in Contrabando, a video which makes me imagine Ingmar Bergman shooting a documentary on the dignity of organic painstaking craftspersonship for some somber European state-television network, or Gertrude Stein offering some witty aside on how today’s contraband (like a preceding century’s camouflage) provides a perfect fusion of human invention and artistic representation and political intervention — all coming together so fast, through some newly arresting mode of artifice that one can only call “modern.” And then I love how the true artistry in this particular recorded performance comes out with the blowtorch and the old-master-like meticulous shading and persuasive chiaroscuro. And the reflective silence throughout this scene kept making me wonder about you, actually, about your own perceptions and feelings, about your own performative role within this video’s real-life smuggling process. Could you describe getting personally involved in the enterprise you document here, and when, along the way, that enterprise becomes an art for you, and for us as an audience?

While having access (for only a couple of hours) to this clandestine location making contraband, my DJing experience came into play — sensing the vibe of the place, where I could go, what I should not do, who I should not look in the eye, how to “feel” this crowd of “informal economy workers.” And sometimes when I work on a project I can feel … this might sound cheesy in a way, but part of the beauty of doing artistic work comes from creating something you know will offer people this extraordinary experience. You can feel it within yourself at the moment when you are entrenched in it. And for this Contrabando video, I just felt that the main character would be this big dense log, which gave me this feeling of how beautiful this piece of nature is, even as it is being manipulated into a smuggling vehicle.

Shooting that video all happened super quick, with a cheap camera — which I didn’t even realize had been set to black and white. When I got there I just thought of Luis Buñuel and early Surrealist cinema. I thought of which shots I could do with just one lens, one tripod, one camera recording over several hours. Or I almost see the 20-minute video as my Babette’s Feast, as a slow-moving piece that gradually reveals itself in the end.

Only when I later started editing did I notice, as you say, that whole influence coming from Bergman and that sort of classic experimental cinema. To me, again, the log itself felt like the principal character — not that slightly scary-looking guy drilling holes into it. The log just seemed so central. It was still alive. It had insects coming out, and I just kept getting more drawn to it. The camera keeps zooming in and out, creating these abstracted images. The whole video only has one panning scene, pulling out right at the end, when you actually see the log in its entirety.

I really love the silence of early Surrealist films. It reminds me of working in watercolors, which I consider the softest medium, and which I sometimes use for the harshest content. So eventually it just felt right, for this video, that the soundtrack should be that material silence you described. You can feel your own body in that kind of silence. You become much more aware of everything around you, and of your movements. I wanted that silence to make you feel more entangled in what this video reveals.

And again, in terms of how the lack of a straightforward soliloquy actually can help an audience feel its way towards something like a reflective, expressive, first-person subject for these videos, I think of Boy in Suitcase, which offers its own aestheticized vision of the precocious perceptions from within the suitcase itself — all amid this extremely risky act undertaken (or at least undergone) by such a small and young child. And when we then encounter a 2001-like finale (to point to just one other film overinvested in music), and when the icon of this boy keeps getting infinitesimally smaller (actually blending with a speck of dust on my computer screen, precisely where a Rothko canvas seems to meet with a Malevich composition seeming to meet with a Turner horizon), I wonder if a Kubrick-esque cosmic embryo might be coming next, and I wonder what else you might have to say about smuggling aesthetics, beauty, even hope and youth into these no-doubt politically charged representations of people facing unconscionably precarious (and otherwise invisible) circumstances. Or why do we, as a concerned but also an aesthetic/reflective/political community, need to see and to appreciate what it looks like from inside the suitcase as much as from outside it?

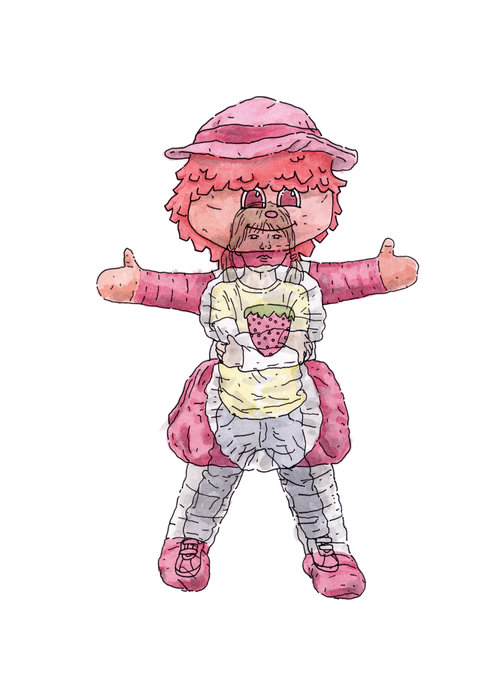

For a lot of the work I do, someone easily can choose to see it more as a protest type of aesthetic, but I do want it to be more subtle, to pull in the audience, and to pull in by the beauty of the colors, the lines, or the sound. The work is formal in that way. I want to seduce audiences to look at the form but then realize: Wait, shit. That’s a little girl hidden inside that piñata, or That’s a boy zipped in that suitcase.

And then more specifically, that Boy in Suitcase video is influenced by summers I spent with an aunt as well. She’d say: “If you keep acting bad, the boogeyman will come and get you. He has a sack. He wants to take you away in it.” For years I had so many nightmares about being in his sack, being taken away, and the sack every time would have this one little hole. And through that hole I could barely see whatever street, people, and landscape we passed through. So when I saw this image from an attempt to smuggle a boy into Spain from Morocco, I pictured his own experience inside the suitcase, and perhaps this suitcase having one small opening (as in my nightmare or dreams), and him seeing little bits and pieces of light and patterns — but most of all just feeling how he felt being inside that suitcase. Again this is basically a video-less video. I found online an X-ray scan of the boy in the suitcase, and then animated the rest of the video, and made it abstract. I didn’t want to reveal the source material for the actual boy until the very end with the X-ray.

I also wondered, with the related Undocumented Interventions watercolors, about you yourself identifying with the US Customs and Border Patrol agents documenting these ingenious attempts at getting people across the border. Did you sense, when working from agents’ visual records, any glimmer of respect for the human invention and courage and determination and beauty and optimism on display? Did the border agents themselves ever seem to enjoy contributing their own artistic witnessings and renderings of such creative acts? And/or does this archive of failed human smuggling point to the most beautiful cases being the invisible (therefore infinitely imaginable) successful attempts? I also think of trans identity, and of any number of forms of not just dramatic border-crossing, but of everyday / ongoing passing and assimilation and hybridity.

Well first, I actually think the Border Patrol agents shoot these scenes pretty accidentally — but with the “wrong pictures” (as in the Warhol examples you brought up, or perhaps John Baldessari) sometimes becoming the precisely right pictures in regards to what they do end up showing and the perspectives they provide. I’ve downloaded more than 800 source-material images through the years. And in the newspaper one day, just as I was setting up a show at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, I saw that image of the little girl smuggled in a Powerpuff Girl piñata. I did more research and learned that all these concealments were taking place where I grew up in Tijuana’s Zona Norte neighborhood. You can get your car altered — for example to have someone sewn into the seat upholstery. Or you could pay $500 to get yourself put into a dashboard, or a couple hundred to get put into a piñata. This area of Tijuana is known for car alterations, and Americans would take their cars to get new upholstery or cheap body work too. They do take US insurance!

For me, this all goes back to our failed border policies. You can build a 20 billion dollar border fence, but people always will find these ways to reunite with family, and to escape violence or desperate situations. They’ll never stop finding creative and ingenious ways to do that.

Of course now you also see a Narco way of doing it, more institutionalized by the cartels, where people pay some organization to help them accomplish this. So probably in the future I’ll want to illustrate some of the more Narco ways of how this happens right now, which all feeds again into these urban myths of the tunnels and of putting people in tires and into the dashboard.

Well in terms of myths and rumors (and also again in terms of your work’s fused atmospheric and aesthetic and experiential and instructive and documentary and autobiographical and civic aspects), I know, from loving your public presentations, how these events and images and textual artifacts resonate when caught up both in broader historical and in imaginary narratives. Could you discuss here having these narratives you’ve encountered or excavated or conjured intersect in such timely ways with contemporary social discussions about our policed and porous borders? When does that acute political overlap offer particularly exciting possibilities? When does that overlap crowd out other aspects of your practice? What other (perhaps often overlooked) ways would you also like audiences to narrativize your greater artistic project or individual pieces?

So let me start with a lecture I gave at the Boston School of Fine Arts maybe five years ago. I actually ended this lecture by showing the Contrabando video. Afterwards, someone immediately asked: “Aren’t you afraid?” I said: “What do you mean, afraid?” “Aren’t you afraid of what will happen to you for doing this kind of work?” And for the previous 15 years I’d actually never stopped to think about that. I’d only thought about telling the story.

Then a couple years later, while working with some artists here in Phoenix, we ended up at a drug checkpoint, and one of them had mushrooms. I think I’ve told you this story. The only thing…well, a lot of things went through my brain. But one basic thought was: Please don’t look me up on the Internet [Laughter]. So I began to get a sense of this slightly more dangerous side of the work I did. But at the same time, it just feels so necessary to tell these stories, but to tell them very differently than what you might see on the news, or might hear on podcasts. Part of this experience just seems so hard to offer verbally through a journalistic approach. You need some sort of synesthesia approach combining sound and image and so on — especially when you want to create space for empathy.

And again, I’ve done this kind of work for a very long time. So I do think it’s the current administration’s rhetoric on the border that really has more people paying attention.

And in terms of telling stories differently, does your work resonate similarly and / or differently for Mexican, or Norteño, or Tijuana-based audiences?

They relate to it more, actually, because someone in their family has done that or does it. When I took part in the LACMA exhibition “Phantom Sightings” that went to the Museo Tamayo in Mexico City, I didn’t know how the work might get taken. But the opposite of what I thought happened. People really got it. They had relatives who have crossed over to El Norte, as they say. They completely understood all of that. And this all takes us back to something you said earlier, and to two basic words that came to me right when I started doing the watercolors: “hopefully invisible.” With the Border Patrol images, with all of the smuggling of drugs and people, that “hopefully invisible” phrase seems to unify everybody.

Yeah, even as you give us these super striking images. And so finally, in relation to all of these different perspectives on your work, and all of the potentially illuminating or obscure tunnel visions in which your work traffics, and all of the under-represented subjectivities your work both shows and stares out from, could you discuss the upside-down shots we get perhaps in every single video — with even explicit upside-down eyes in Interrupted Passage?

In cinema, people might call that a cheap trick [Laughter]. In video, it adds a little more drama and tension — almost as if the images are going to fall off and hit the ground. Or for me, it just takes us back to the familiar saying that truth is stranger than fiction. When I alter the framing, it feels almost like a jump cut. I do it to disrupt the flow in a way. I don’t always want a piece to flow so well. I want a contrast, something to start breaking up the narrative. Putting things upside down can break up the rhythm. In DJ terminology, when a DJ reaches a certain peak with everybody dancing, she or he then puts on a “dancefloor killer.” The dancefloor killer just kills the vibe, and people stop dancing, and clear the floor, but giving you an opportunity to build it back up again!

All images courtesy of Gallery Wendi Norris.