I met Jonathan Blum at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 1996. We sat next to each other in literary seminars that spanned an extraordinary arc in time and geography, from Achebe and Anderson to Zi and Zola, from the Tao Te Ching to the Old Testament and back again.

We wrote for hours and hours and spent even more hours talking about writing after that, smoking our unfiltered cigarettes and taking apart sentences. We meditated on the dramatic spaces between words, pored over meter and rhythms and the transitions between paragraphs, and argued about the mysteries of how stories we love began and ended and how great stories never seem to leave a body once they’ve entered it, how they live on in the soul forever somehow, haunting it like welcome ghosts.

We read the dictionary like a holy book, injecting words and their definitions into our eyeballs, listening for hours to taped recordings of many of the greatest stories and poems in the English language read aloud by their authors, contained in the vast archives of the Workshop library. And we ate an inordinate amount of beef dumpling soup together in the back room of a Korean grocery store that doubled as a video rental emporium called Chong’s.

During our two years in Iowa City, we were never assigned to the same workshop, but our connection outside the workshop, which has bridged the past two decades, as colleagues, readers, and friends, and especially as devotees of the American Short Story, has been one of the most rewarding of my life as a fiction writer.

There are many stories in my first book and certainly ones in the collection I’m working on now that would not be what they are without the benefit of Jonathan’s insights in early and later drafts. And the conversations we have had about stories, about writing and the vicissitudes of the writing life, shared through the years at hole-in-the-wall takeout restaurants from Brooklyn to Los Angeles and points in between, have fed my soul.

Our favorite spot to meet these days is at a Lebanese place called Hayat’s Kitchen in North Hollywood. It’s on Burbank Boulevard, kitty corner from Circus Liquor and next door to a butcher shop that sells things like ostrich kebabs and antelope meat. And because we are just as devoted to the varied tapestry of the San Fernando Valley as we are to the short story, we decided to meet here for falafel and garlic fries and talk a bit about The Usual Uncertainties, which is Jonathan’s second book.

¤

HOLIDAY REINHORN: In recent years, I’ve had the opportunity to closely read many of the stories in The Usual Uncertainties during the drafting process, and while there is so much to discuss about the inner geography of the characters that makes them unforgettable, I don’t think it would be possible to approach these stories without first discussing the pivotal role that South Florida and the city of Los Angeles play in this book. One of my favorite stories in the book in fact is called “A Certain Light on Los Angeles,” which was written in 2017. Can you speak to that a little?

JONATHAN BLUM: I grew up in Miami in a fairly observant Conservative Jewish home. I went to a Jewish day school, and the small synagogue we belonged to played an important role in my upbringing. I looked up to my rabbi and, for a time, thought I might become a rabbi myself.

When I was 18, I bought a one-way plane ticket from Miami to Los Angeles. I wanted to try and make it as a musician and songwriter, but within a year of living in Los Angeles, I could see that I didn’t have the talent. It was at about that time, when I was taking literature classes at a community college, that I read What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. It seared me. Raymond Carver had a way of seeing the world that was unmistakably his own. The work was dark, sad, funny, intimate, complex, American. Characters behaved well, characters behaved badly. I quickly came to love his entire body of work, as well as the short story itself.

So I started writing stories when I was 19, but I was trying not to write about Miami or Judaism or myself, and when I did write about those things, I didn’t do it well. Over the next few years, I moved several times — to San Francisco, Napa, back to Los Angeles, up to Oakland. Finally, at 28, when I wrote “The Kind of Luxuries We Felt We Deserved,” I felt that I was beginning to capture something about the Miami of my imagination, the Miami that you could not visit but that lived inside of me.

I love the idea of stories being a kind of shared living embodiment of place and memory. Can you speak a bit about the title of the book? When we meet all the characters, they are being faced, albeit differently, with a kind of “high octane” version of uncertainty and are being tested with things which will alter their interior and exterior universe in both dramatic and subtle ways. I think of the opening story, “The White Spot,” in particular as an example of this.

Well, first, I love the word uncertainties. I remember as a young person reading John Keats’s letter in which he praises the kind of writer who is “capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact & reason.” Perhaps, I thought, I can be that kind of writer. Uncertainties govern our lives and, some would say, offer us the opportunity to experience meaning and beauty. And what are uncertainties if not ordinary and frequently occurring?

Two of the big uncertainties I think we all face are who can we love who can love us, and when and how are we going to die. Both of these are brought out in “The White Spot.” That story began when I decided to write about a father and son. I didn’t know what their relationship was exactly, but I knew love was a component of it. Perhaps the love would be expressed indirectly, but it would be there. Also, the father’s difficulties with loving were written into the story. He has just gone through a bitter divorce with his son’s mother, and he is not close with his parents.

As for death, being a pulmonary physician means that you are going to eventually lose many of your patients. It’s only a matter of when. And in the story the son tries to learn from the father how to predict the death time of a patient. The son is fascinated with his father’s understanding of death and his acquaintanceship with it. On top of all that, the son’s grandparents, whom he reveres, are Hungarian Holocaust survivors, so they have an understanding of when death is coming that is almost unspeakable.

On the flip side of this, I would also love to talk about how funny this book is. “The Kind of Luxuries We Felt We Deserved” and “Roger’s Square Dance Bar Mitzvah” make me laugh out loud.

I’m glad. I too love laughing out loud when I read a story.

I wrote the first draft of “A Confession in the Spirit of Openness Right from the Beginning” when I was, improbably, living in a 15th-century Scottish castle (on a Hawthornden Fellowship), and I actually laughed out loud while I was writing it. I wasn’t trying to make the story funny. But as I realized what it was going to be about — a man who writes an email to a woman he has just gone on a first date with, asking her out for a second date but saying things to her that could be considered wildly inappropriate — I just laughed.

“Roger’s Square Dance Bar Mitzvah,” to me, has so much unhappiness in it that if it brings anyone the pleasure of laughter, I am delighted.

What roles do Jewish literary tradition and the Hebrew Bible play in the book? I know you love the Psalms.

Big question. First of all, I can read Hebrew and pray, but I last spoke Hebrew somewhat proficiently when I was 16, and now it’s gone. That said, I still look at the Hebrew side of the Tanakh when I’m looking something up, and I dream of living in Israel for long enough that I would regain proficiency with the language.

I would characterize my relationship to Jewish literary tradition this way: it’s all connected. My great-grandmother left Bukovina, where Aharon Appelfeld was from, around the start of the 20th century. If she had stayed in Bukovina, then a couple generations later, she might have wound up, like Appelfeld’s mother and grandmother, shot to death, or else butchered and buried in a mass grave. I have a response to Jewish writing that is different from my response to other writing. I remember reading the Victor Klemperer diaries and needing to put them in the hands of everyone I knew. Look at all he noticed and preserved!

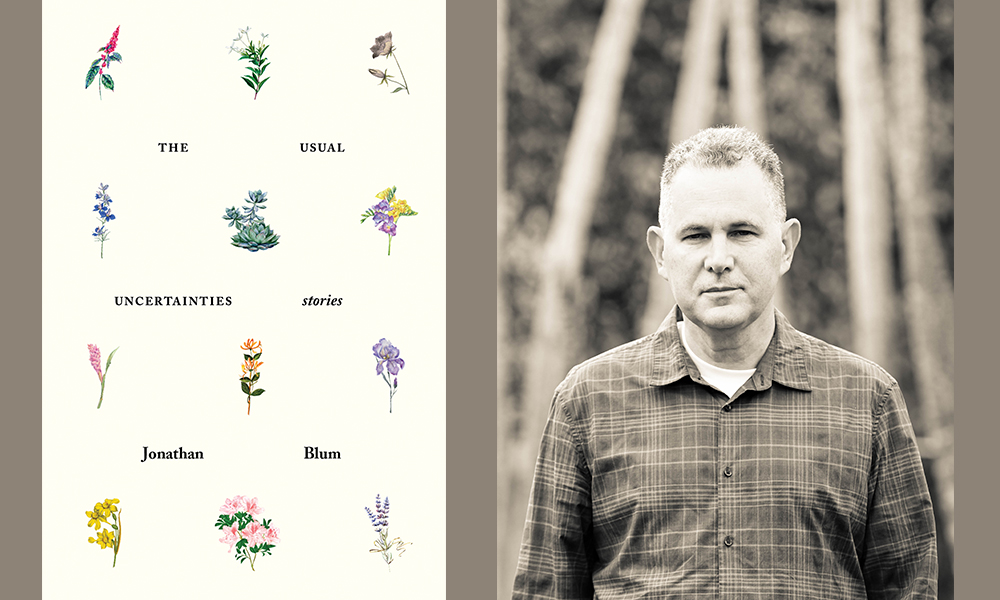

The Psalms partly inspired the cover of The Usual Uncertainties. Seven of the psalms are acrostics. In these poems, the first verse starts with the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet, the second with the second, and so on. These are songs of praise. In “A Certain Light on Los Angeles,” Adam, who comes from an observant Jewish home, takes Jeeranun, his Thai immigrant girlfriend, to the Los Angeles Flower Market early one morning and buys her a large bouquet of flowers, which he selects for her alphabetically — amaranth, bouvardia, campanula, and so on. He is showing her the pleasures of knowing English. The Psalms aren’t mentioned, but they’re there. On the cover of the book, you will find a dozen flowers, arranged alphabetically — amaranth, bouvardia, campanula, and so on. The artist, Sevy Perez, who created the cover, told me he wanted it in some way to reflect the psalms I had shown him.

You have pointed out to me that the Psalms were meant to be sung. Music plays a big part in your stories. Can you touch on that?

Some members of my family, including my mother, have beautiful singing voices. I wouldn’t say my family is particularly musical, but a lot of the characters in my stories are. My first published story was about a bipolar jazz pianist who is telling the story of the loss of his wife and his mind. That story took me years to write. A square dance, of course, involves music, and then there is the 1940s- and 1950s-era music that appears in “Apples and Oranges.” Music, for me, is a trigger of memory and the accompaniment of many important occurrences. Listening to music is, in itself, for me, an important occurrence. As a teenager I loved hearing the Song of Songs chanted, and there were days I couldn’t wait to get home and listen to Tom Petty sing “Refugee.” I have listened to The Well-Tempered Clavier a hundred and fifty times.

It has been observed that of all the art forms, the short story is best suited to revealing the depths of the human soul. What is it about short stories that you love most?

Maybe it has something to do with the fact that I often prefer the three- to five-minute song to the larger musical work. Not always. There are collections that offer immensely more than any single story can offer. But with songs, you can hold the whole thing in your mind. You can hear it all at once. Same with stories. I have held “Good Country People” in my mind. I have held “Emergency” in my mind. When I give a student a short story like “The Lady with the Pet Dog” or “Lawns,” I am hoping it will give her something along the lines of what it has given to me.

Yes. I love ending on the idea of stories being a shared gift. The making and realization of this book of stories certainly has been that to me and I’m so looking forward to it reaching its readers. Bon Appétit!

Jonathan Blum and Holiday Reinhorn will celebrate the publication of The Usual Uncertainties with a reading of their newest work at The Last Bookstore in DTLA on November 25 at 7:30pm.