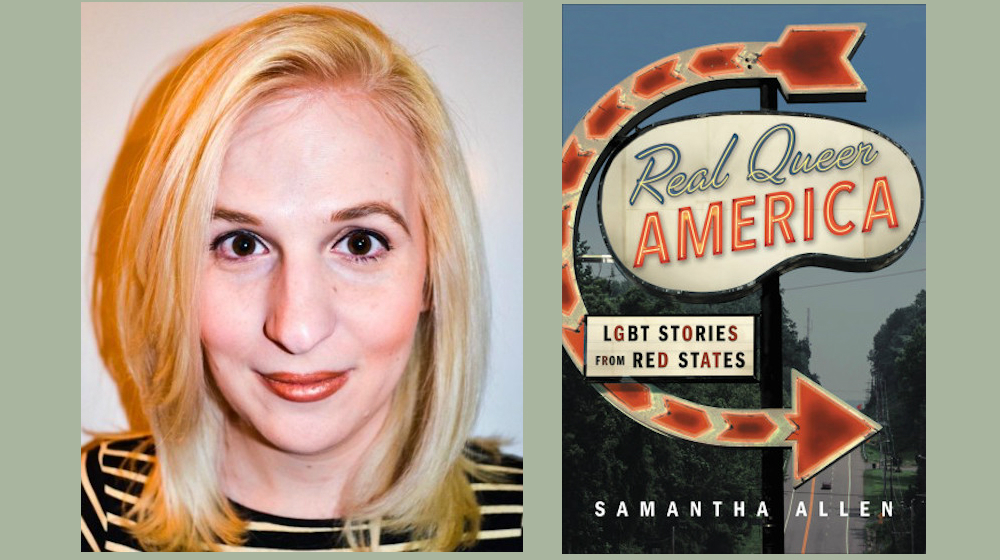

About a year ago I was sitting with the writer Samantha Allen and her wife Corey (I didn’t know they were married just then) in a hipster pizza bar in Tampa, Florida, where I live. Allen, an award-winning reporter who writes on LGBT issues, had just finished the cross-country road trip she recounts in her new book, Real Queer America. It’s a smart, funny, sociological odyssey through LGBT communities in so-called “Trump country,” a book that resists easy classification in exciting ways. Allen’s sister is my wife, which accounts for some of my interest in her writing and career, but far from all of it. Her work has the academic’s passion for high, important ideas, tempered with a journalist’s suspicion of the needlessly difficult. The result is a smooth and vital voice on the page, by turns personal, lyrical, and analytical. And it’s this same voice I was enjoying in conversation at the pizza joint, when our server came over to the table and had no sooner looked at my dinner companions than started hitting on them. He wanted to know what the beautiful ladies were doing out tonight — a special occasion? Or just relaxing? At one point he asked Corey about her friend, and Samantha said, “Actually, I’m her wife.”

“Oh, cool,” said the server. “That’s awesome.”

And that’s how I learned Samantha and Corey had gotten married.

In Real Queer America, Allen writes about this protective habit of keeping cards close to the vest — not around the elective family she gathered up during and after her gender transition, but around people like me, the friends and family members who had “too many memories of [Allen] before transition, wearing cargo shorts, dating a straight girl…” And yet the book ultimately recounts how Allen’s parents, devout Mormons, called her up one day and offered to pay her wedding expenses. And how she and Corey had cried at the news.

It’s a complicated, rich story, one of many in the book that looks to shade in our black-and-white narratives around queerness — and pop certain other binaristic balloons we might be carrying around. Time and again Allen talks with people who’ve left queer meccas and moved to redder states, over the worried objections or smug predictions of friends: You won’t last a year out there. Then the same people find that life in the badlands of Utah or Texas or Indiana isn’t only more possible financially, but it isn’t bad. There’s a place for them there, a community to be a part of and help grow.

¤

RYAN MCILVAIN: First off, I want to talk about some nerdy craft stuff. From what I’ve seen, not enough of the coverage has talked about how beautifully dressed this book is…

SAMANTHA ALLEN: Oh, the readers have been very kind in terms of their compliments on the writing and the craft of it, but I think it’s totally understandable that media coverage is mostly going to focus on the subject matter. LGBT people in red states is one of those topics that everyone wants to discuss, everyone has some sort of personal connection to it — they’ve got a gay uncle in Nebraska or they themselves came from Ohio or Arkansas or somewhere. I certainly don’t begrudge people wanting to have subject matter discussions about it, but it’s nice to talk shop.

I was struck by how you wove all these different kinds of writing together — memoir and journalism and social commentary and theory. Were you teaching yourself how to write this book as you wrote it, or did you have a plan going in?

It was a hard book to pitch because I did have this vision of a memoir/deeply reported nonfiction travelogue — I had that idea for it in my head and yet it wasn’t easy to articulate necessarily. I was fortunate to find an editor at Little, Brown, Jean Garnett, who just totally got the vision for it. I knew from the beginning that I wanted it to be less of a bird’s-eye sociological survey of LGBT life in Middle America and more of a personal narrative tour through communities, a kind of slice-of-life book.

And with a decent amount of theory thrown in too. I know with some of your earlier work you’ve had editors saying, “What’s with all this theory shit?” Did you run into similar resistance with this book?

I was encouraged to put more queer theory into the book — those were some of my editor’s favorite parts, whether I was talking about Eve Sedgwick, José Muñoz, Lauren Berlant and Michael Warner’s theory of queer world-making, or Kimberly Crenshaw’s idea of intersectionality. And you know, as a recovering academic myself, I sort of relished the opportunity to take these concepts that were introduced to me in an arcane and sometimes intimidating setting and try to put them into a book that I thought people could pick up and read on an airplane.

A lot of the book is you going around the country and hanging out with friends, meeting strangers along the way. I was impressed with your ability to achieve a similar feeling of intimacy both with old friends and complete strangers. How did you manage that?

Well, first of all you’ve caught on to my grift — it’s all been a long calm to get travel funding to see friends. And you’re right that a lot of the book is me parachuting into the lives of perfect strangers and asking them to share their stories with me, and that’s something I think about all the time in journalism. And I think the way I sort of mitigate how I feel about that ethically is by displaying vulnerability myself, you know? When I’m talking to the parent of a transgender child and their child in the same room, I’ll talk about my coming out story and my experiences being transgender and my experiences with my parents and my family. I think I sort of owe it to interview subjects to be vulnerable and honest with them if I’m expecting them to be that way with me.

You must have had the basic thesis of the book in mind when you started out — that more and more queer people are living their lives in red states, and enjoying their lives there. I wonder where this thesis was most confirmed or challenged.

I would say the thesis was really challenged in Mississippi, mostly because it’s such a hostile state to live in — not just for LGBT people but for young people generally who need a more thriving and modern economy than Mississippi has to offer right now. I know both Kaylee Scruggs and Tyler Edwards, who I interviewed in the Mississippi chapter, have really pained relationships to that fact because they love the culture of Mississippi but can’t see themselves building a life there. Tyler moved away, actually, shortly after I finished writing the book and Kaylee is in Atlanta now — but even in Mississippi I still came away with some glimmers of optimism, from my experiences in Wonderlust and the Fondren District.

And I would say where I had the thesis confirmed in a way that surprised me was in Provo, Utah, a place I know you and I both have history in. For me the Provo of 2005-2007 didn’t feel like a place where LGBT people could exist, even though I’m sure in hindsight there certainly were LGBT people going to places like City Limits Tavern and elsewhere — but to go there and to be sitting in the LGBT youth center, Encircle, across the street from the Temple, was an out-of-body experience, even knowing in advance that Encircle existed. Sitting across from the symbol of a God that I thought at one point hated me and was going to send me to hell, sitting in that environment with LGBT Mormon kids was just wild, for lack of a better word.

Mormonism’s vision of an anti-LGBT God hasn’t changed all that much, though, has it? When you were talking to these people did you ever just think, with all due respect, what the hell are you still doing in the church?

Well, I didn’t take any 15-year-olds and shake them by the shoulders and ask them that, but I certainly talked about some of those issues with Emmett Claren. And that was a moment for me where, being ex-Mormon, I had to just kind of not try to … I don’t know. As an interviewer you definitely want to get inside the interiority of people’s brains, but as a human being you just have to respect sometimes that faith and belief don’t follow the lines of logic that you want them to. I sort of reached a point with Emmett where I was like, No, I don’t need you to explain to me why you want to be involved in Mormonism, I need Mormonism to explain to me why it doesn’t want you.

It occurs to me that the generational shifts you’re seeing in Mormonism might be representative of larger trends in the country. Were there other generational differences or other areas of resistance you encountered in writing this book?

First of all, I’d say that social attitudes toward LGBT people have been changing so rapidly that people of different generations can have vastly different experiences. I’ve had people come to me, for example, with stories of deep trauma in red states, so I wanted not to sugarcoat those things in the book — I think I did my due diligence in terms of expressing how dire the situation can still be for LGBT folks in America. At the same time, I did want to stress the message that progress is happening and it’s happening everywhere, it’s happening now.

In terms of resistance, I’ve probably gotten the most emails from folks who think I go too hard on New York…

Oh that’s hilarious. I love that.

Well, look, I want to set the record straight and say that some of that animus toward New York City in the book is firmly tongue-in-cheek — but it’s also not my favorite place in the world and I’m not shy about that within the pages of Real Queer America. I think you do have folks who came to New York at a time when that was their first exposure to a diverse city, a place where they could finally be themselves, and I don’t want to stamp all over that personal meaning. I’m coming to it from the perspective of a 32-year-old millennial dealing with life in a world where I feel like I’d have to move to New York to progress in the industries that I work in, yet doing so would mean I would have no money. Also, the things that people say they have access to in New York I’ve been able to find literally all over the country. I did want to challenge that sort of exceptionalism that we’ve built up around places like New York or San Francisco when it comes to LGBT culture.

I hate giving the man more air time, but I have to ask. How do you fit Trump into your book’s narrative of LGBT progress?

My read on Trump on LGBT issues is that he’s largely transactional. He’s done things like the transgender military ban, or the February 2017 rollback of transgender restroom guidance — and he’s presented these as gifts to the religious right and to his vice president, whose positions on LGBT issues are well-known. I think in the long term there’s no stopping LGBT progress, but maybe the under-told story of the Trump Administration is the way he’s been stacking the courts with judges whose positions on LGBT issues are less than ideal, to put it mildly. And given the number of court cases going through right now about things like LGBT employment rights or anti-LGBT discrimination in a business setting, those court picks are going to pay dividends for anti-LGBT groups for years to come.

At the same time, if you look at not just where public opinion is right now but what the trend has been for the last few years, anti-LGBT Americans really are a shrinking minority. When I seek to explain and understand the phenomenon that drove Trump to power in 2016, I don’t necessarily look at LGBT issues as my first stop. I look at issues like race and immigration and the economy, which I think are much more powerful motivators for Trump supporters than hostility to LGBT people — although we certainly do see that hostility among the Trump base.

Can I ask you a question about the family?

Shoot.

I was really moved by how you wrote about us all, especially your parents. And it didn’t feel like you were pulling your punches so much as coming to a moment that I guess we were all traveling toward, with everyone more at ease around each other. What have your parents said to you about the book?

Well, my mom/Nina sent me a very kind email after she read the book. I think, like many upper-middle-class white Mormon families, we don’t always express our feelings to each other in the most direct way, and there was stuff in the book she was surprised to hear about. I think it offered her a window into a kind of lifelong struggle with gender identity that she didn’t always see in me, and I think the process of writing it, and her reading it, was healing for both of us. Even if we didn’t have some big epic conversation afterward. It’s a hell of an indirect way to have group therapy with your parents. And what is memoir but self-therapy, right?

Amen.

I’m also remembering something else I wanted to mention, from a queer theory perspective. You’ve obviously read how I chose to end the book with the image of your son Jamie looking at a mermaid show, in Weeki Wachee, Florida, and in that section I’m thinking about what Jamie’s life will be like, how his generation’s attitudes on LGBT people are probably going to be just blasé, you know? “Oh, cool, you’re non-binary? Do you want to come over after school and play Fortnite?”

I think when I was in graduate school, I took a more cynical, Lee-Edelman-No-Future-esque perspective on LGBT issues and family and heteronormativity. I was very much anti-futurity, thinking that futurity was inherently heteronormative and that kind of thing. And I feel like since leaving the academy and actually trying to trace queer theoretical concepts in my life and in this book, and also just interacting with real people — real LGBT people of various classes, races, and backgrounds — I’ve come away with more of that Muñoz perspective of queerness as a sort of undying optimism that propels you forward into uncertain circumstances. I think becoming an aunt, frankly, to your children has been a part of that evolution, too.