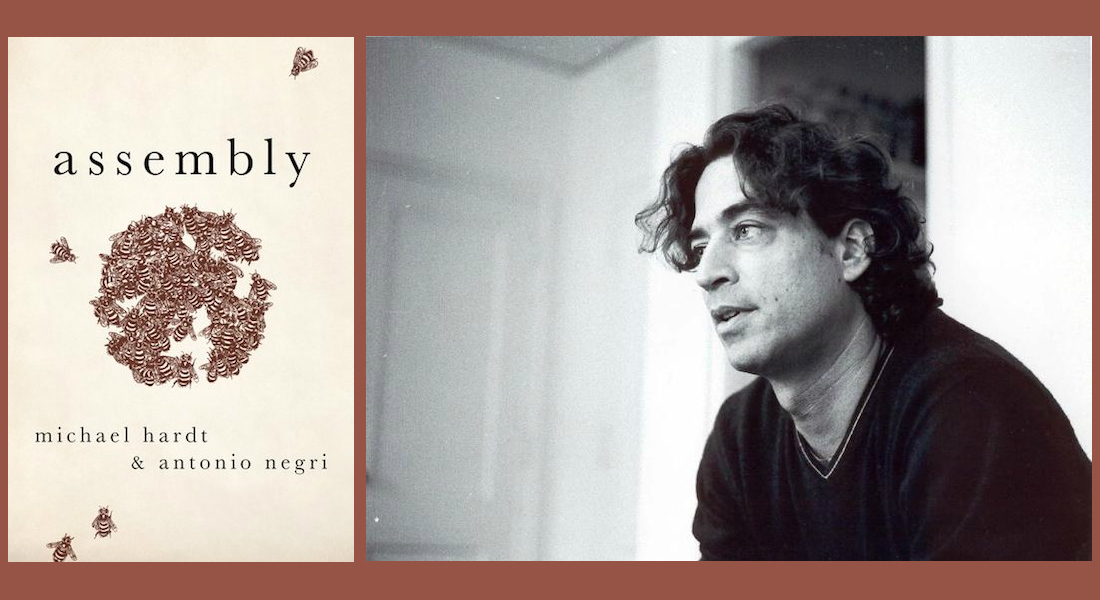

What constructive public conversations and communitarian projects can start from the shared recognition that “people aren’t born with or immediately given…the learned (rather than natural or inevitable) capacity to decide politically together”? What can our own present-day social experience nonetheless teach us about how further to harness catalyzing political agencies (“moving from the most local nature of prefigurative practices in the public square, towards a middle level of antagonistic reform efforts within the system, to the largest level of taking institutional power”) from the past 15 years — as exemplified by Occupy encampments, Podemos electoral campaigns, and the ambiguous record of avowedly progressive administrations in countries like Brazil and Bolivia? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Michael Hardt. This conversation, transcribed by Phoebe Kaufman, focuses on Hardt’s most recent collaboration with Antonio Negri, Assembly. Hardt teaches in the Literature program at Duke University, where he also co-directs the Social Movements Lab. He is author (with Negri) of the Empire trilogy (Empire, Multitude, and Commonwealth), and serves as editor of The South Atlantic Quarterly.

¤

ANDY FITCH: With “assembly” here defined as “the power of coming together,” could we start with this book’s “we,” a “we” which, at various moments, might suggest you and Antonio Negri as a collaborative duo, or the text and its reader amid their own dynamic exchange, or some galvanized multitude of partisan combatants, or even some Rousseauian generalized will suddenly crystallizing towards articulation, even a sovereign-power-esque royal “we” exercising its privilege to speak for all? One response to Assembly might seek to parse such constructive and/or confusing overlaps and entwinements of first-person-plural subject-position across this text. Another reading, however, might suggest that the dense textuality developed through these perspectival interplays deliberately enacts its own rhetorical excesses and overflowings, probing possibilities for polemical, philosophical, scholarly, lyrical writing to foreground its own generative production/reproduction of subjectivities. Or one could consider how the amorphous “we” apparently driving this text emulates the new type of leadership Assembly calls for — a leadership of ever-shifting context-specific tactics and gestures, rather than a totalizing, top-down, definitive, implementable, paraphraseable, assertively authorial presence. Or the prefatory line “All this must be constructed materially” re-attuned me to the reality that Assembly offers a material (here textual) artifact of your ongoing, affect-heavy, loving, socially cooperative and productive relationship with Toni, and to the possibility of us discussing that particular lived history of the “we” in greater concrete detail. Or this fluidly stable/unstable “we,” providing syntactical traction more than identity-affixing political prescription, seems almost its own Spinozan internalized machine (as do call-and-response passages stitched into this text’s structure), providing not so much conclusive, tension-resolving answers as further syncopated forward-propulsion.

MICHAEL HARDT: That’s great. First I probably should say a bit about me and Toni, about this dynamic of writing with someone. A lot of our process involves speaking to each other. And then when we write, we often imagine ourselves speaking for the other, following up on thoughts the other has initiated. We end up neither writing in my voice nor Toni’s voice, but really some third voice.

So that’s the lived space this “we” comes from, though you had directed us towards a more interesting political question. I take quite seriously the leftist political mandate from the last several decades that one should never speak for others. And this mandate, coming out of anti-racist and feminist writings, came along with the mandate to write from one’s own lived experience. So from those two concerns came a great distrust of implications attached to the first-person plural — certainly the royal “we” you mentioned, but really any invocation of a “we.” At the same time though, even as Toni and I want to recognize and avoid speaking in the name of others, we do still want to propose a collective subject that can operate as a kind of invitation.

I consider that kind of proposition really important in our writing. Our books will propose a political argument then try to follow it to its farthest point. In some ways, that ends up creating a polemic, I suppose, but hopefully a useful one for readers to work with, gauge themselves against, maybe feel a certain belonging to. Our books don’t present constant hesitations. They don’t question their own voice. They don’t even question their own political positions. Instead they try to follow through as thoroughly as possible on extending that invitation to an available collective subjectivity, and then let readers decide whether or not this fits them.

Your books do often seem to gesture towards a catalyzed/catalyzing emergent collectivity. And in terms of where this catalytic process might take place specifically amid a reader’s experience, in terms of how and where Assembly’s invitation gets registered, in terms, still, of pronouns, this book’s polyvocal “we” also pointed me towards pluralities lurking within the purportedly individual “I” — as in, say, Walt Whitman’s classic “I contain multitudes” formulation. And so I wonder if providing working descriptions for a few of Assembly’s key terms here might help. Your book’s closing “Exhortatio” section, for instance, melds social assemblies and singular subjects themselves composed by processes of assemblage (with such assemblages here defined “no longer by their possessions but by their connections,” with such assemblages integrating “material and immaterial machines, as well as nature and other nonhuman entities, into cooperative subjectivities”). Or with, say, Assembly’s recurrent metaphor of a dispersed socio-chemical precipitate suddenly solidifying into coherent formation, how might Assembly’s galvanizing calling forth of a “we” prompt equivalent emergent agencies within an “I”? How can this writerly/readerly “I” both become the “we” and learn from the “we” at the same time?

Yeah I could see it making sense to start with rethinking the individual subject and to recognize, with Whitman, that each of us contains multitudes. Though that’s only part of it because, as you point out, this would have to involve rethinking the subject not as defined by its possessions, but by its connections. For that large task, a particular philosophical tradition has tracked how the modern, individual subject often coincides with the development of capitalist society, and gets defined by what it has (whether the possession of actual physical property, or even the possession of abstract qualities like courage, beauty), rather than by what it is or could become.

So here we want to try out constructing a new type of subject on two different axes: a subject already plural, and a subject defined not by property, not even by immaterial properties. Putting together those two conditions leads to a notion of multitude, and to thinking of multitude not solely as a social plurality of humans, but as potentially including broader connections, to other species and to the physical world. Here that notion of the machinic assemblage you mentioned definitely does provide one avenue. We actually draw from many different traditions to try to show how the many can not only cohere, but also act together — to show that we and that even you don’t need to speak from a single voice, don’t need to take dictation from some central authority, in order to act coherently politically. And here the “new Prince” emerges as our way of rethinking the notion of the Prince as inherited from Machiavelli and a long tradition since him.

Along similar lines of how Assembly’s reader might reflect on and rethink the “I,” could you flesh out this book’s distinctions between neo-liberal foregroundings of self-interested individuals, and your own foregrounding of singularities — with singularities perhaps best conceived as vectors of autonomous selfhood and social cooperation, dissolving reductive public/private dichotomies? And I guess subjugation and subjectivation also might come into play here. So again, how might Assembly’s kaleidoscopic contextualization amid an ever-shifting “we” prompt a reading “I” not only to recognize power’s infringements upon everyday subjectivities, but also newfound prospects for resistance and for liberatory potential? How does the ghost of the autonomous, integral “I” haunt this book’s materialist machinic construct of its “we,” and/or vice versa?

Our interest in the concept of singularity arises sometimes in relation and sometimes in opposition to the notion of identity. Often when trying to recognize social differences (racial differences, gender differences, differences in sexuality), one poses these in terms of identity, a concept which itself imposes a unity in order to recognize difference. Here we use the concept of “singularity,” by contrast, to think about identity as always in the plural, as always multiple both externally and internally. One can certainly recognize this argument for multiplicity within identities expressed by feminist traditions and Critical Race Studies, although they don’t use the term “singularity.” We want to conceive of singularities, then, as inherently multiple subjectivities, as multiple collectivities, and as multiple in time (by which I basically just mean always in a process of becoming) — whereas one generally imagines identity as something fixed in time. So again, one might think of singularity and multiplicity as opposites, but in fact we understand singularities as always multiple, which allows us to approach questions of identity while avoiding some common pitfalls associated with political thinking about that topic.

Well returning here to your title, and to how an ever-present pivot from assembly to assemblage (and back again) plays out across this project, I ask about the “we,” the “I,” in part because your book kept raising for me broader questions of how to outline, address, enact assembly at present without producing/reproducing/reinforcing polarity and its divisive fragmentations. A multitude creating new subjectivities can sound innocent, benign, empowering, liberating; a concentrated social power imposing subjectivities can sound oppressive. But how much in fact does the former differ from the latter here, and can you further describe the subjective/intersubjective dynamics implicit within that difference (again maybe in part by differentiating between subjectivation and subjugation)? We also could address more localized concerns regarding exclusionary dynamics of group formation — asking for instance how avowedly progressive movements themselves might reflect undertheorized social hierarchies, with the glaring example of the iconographic straight-white-male worker monopolizing labor’s image repertoire for much of the last 150 years. But in any case, if we can agree that polarity along various demographic and/or ideological lines works to maintain present-day power relations, does it become important for assemblies as you conceive them to smash polarity as you want the state smashed, not by annihilating an opponent so much as by reconfiguring broader networks of relations, identifications, conceptualizations?

To start with, one foundational problem Toni and I have worked on from various approaches in different books has involved rethinking the concept and practices of democracy. Democracy, in its basic formulation, offers this very simple and straightforward idea of the rule of all, by all. Of course, difficulties arise even before you figure out how to put that idea into practice. In some ways, democracy has to include a concession to multiple perspectives and to encouraging everyone to participate without abandoning who they are and what they want. But it also has to bring forth a crucial capacity that people aren’t born with or immediately given — the learned (rather than natural or inevitable) capacity to decide politically together.

Thinking about this particular capacity can help us to distinguish among different types of assemblies. Obviously not every assembly, and not every social movement, is progressive. It’s important to work out criteria for how to categorize or judge them politically. This task can become all the more difficult when you recognize that reactionary social movements often adopt or mimic characteristics or practices of progressive movements (even of liberation movements), and reflect these back in distorted fashion. I remember, for example, from the 1980s, the practices of the anti-abortion group Operation Rescue, which would conduct peaceful sit-ins around abortion clinics and hang limp as they were arrested by the police. If you were just to see the images on TV or in the newspaper, you could easily be confused about what was going on. Operation Rescue took an element from the repertoire of the preceding decade’s student movements and anti-racist movements. In Assembly we talk about radical organizational forms and political practices getting reflected in a dark mirror, by right-wing movements, always with a distorted view. But much more important than the superficial resemblances of these practices, of course, are the fundamental defining questions we’ve mentioned about unity, multiplicity, and democratic participation. Liberation movements and reactionary movements define and distinguish themselves right there.

Let me approach this point from another angle. Toni and I have often, tentatively, tried to work through a political notion of love as a force of liberation. But again, one also has to recognize that reactionary social movements, that some of the most violent and terrifying reactionary social movements, likewise operate out of love. Even so-called hate groups, white-supremacist groups, see themselves as based in love. They love what is the same. They love whiteness, white people, and certainly they hate others though that is not their primary consideration. This is a tragic, horrible mode of love that refuses multiplicities. But that shouldn’t lead us to disqualify love as a progressive political force. Those varying possibilities pose, instead, a basic criterion for judgment, for distinguishing among political modes of love. Here, then, is a first rule: a political love capable of liberation must not reinforce a unity but engage and form bonds with multiplicities.

In terms of tensions between unity and multiplicity, between democratic representation and capacities for civic participation, and again in terms of how to take power differently, how to opt against attempts to become the new sovereign (instead dismissing claims to sovereignty altogether) — when this particular type of power-taking gets described as “producing independent institutions that demystify identities and centralities of power,” I’ll wonder how such productions might constructively or combatively align, say, with Tocquevillian notions of an empowering participatory democracy and the subjectivities that such participation creates, or even with present-day conservative calls for increased federalism (Assembly does, for instance, associate some federalist models with a constructive form of “pluralized ontology”). Tocqueville might seem a suspect figure in this specific historical account, but since Machiavelli gets rehabilitated, I thought I’d at least try. Assembly seems to assume that even a quite participatory democratic republic would not sufficiently subordinate leadership to performing something more like a tactical/technocratic executive function. But why couldn’t it? I guess I’m asking for a bit more clarity on precisely when does Assembly critique prescriptive blueprints for democratic government shaped by political representation, when does it critique specific real-world democracies for lacking sufficiently proactive civic participation, when does it say that neither democratic representation nor democratic civic participation can help us much anyway? When, in your opening “Where Have All the Leaders Gone?” chapter, the Parisian Communards recognize that “they were not satisfied to choose every four or six years some member of the ruling class who pledges to represent them and their interests,” do you mean to suggest to present audiences that representative democracy categorically allows for no other possible outcome, and, if so, could you further substantiate that claim?

Here I might switch from Tocqueville to Madison, actually. I take Madison at his word in the Federalist Papers, where he insists on representation against democracy. Representation has a double function in the thinking of the Federalists and the constitution drafters. With Madison and Hamilton, the constitution picks up a double function of, on the one hand, linking representatives to the represented (through electoral means and others), but on the other hand deliberately detaching those who rule from the represented. A great and lasting conceptual confusion comes when, not long after the U.S. republic’s founding, representation (which, again, Madison proposes against democracy) gets recoded as democracy itself. We have to hold these two concepts apart. I certainly prefer representation to tyranny. I consider representation better than centralized, sovereign decision-making. But I still feel the need to differentiate representation from democracy.

Democracy means that people do not give up their political decision-making, whereas representation requires that people be dispossessed of their decision-making powers, that they give these over to representatives. So Toni and I want to ask: “What would make democracy possible today? How might people govern together by maintaining their political decision-making powers?” I agree that one can’t take some dogmatic stance on these types of contemporary questions. So Toni and I certainly would participate in and work through electoral projects, especially those trying to pose a transition towards more democratic forms.

Keep in mind too that two different temporalities always play out in this type of political reasoning, such as our critique of representation. From a long-term perspective, one can adopt a principled reasoning to think through what we want ultimately. But from a perspective addressing the immediate state of things, you do have to embrace an approach more like a vector, or a mixture. Democracy’s ultimate goal, it seems to me, involves finding a way to dissolve the kinds of separation that representation imposes. But certain modes of representation actually can help move us towards that.

In terms of how/when democracy becomes possible, in terms of how you might situate yourself in relation to present-day electoral politics, but also in terms of temporal mixtures, I wonder if we could discuss a bit political counterpowers. Here could we more directly address your critique of liberal assumptions that a more fair and equal mode of political representation can provide “the royal road to democracy”? You trace a historical pattern in which radical resistance both to private capital and to the state’s complicities subsequently gets reframed as an achievement of the public sector and of the state itself. You present an alternative to hypocrisies on the right (endorsements of freedom without equality) and on the left (endorsements of equality without freedom), in the form of effectively institutionalized political counterpowers (plural, linked in coalition, making nonsovereign claims to authority). So to provide concrete examples, to flesh out further your formulation of Machiavellian realism, as well as the textured political temporalities you’ve described: when historically or where at present have political counterpowers most productively combined (not just in political spheres, but social spheres as well) exodus strategies (creating a new “outside” within the dominant structures of society), antagonistic reformism (engaging with and trying to reshape existing institutions), and hegemonic power-taking (directly transforming society as a whole)?

Well it’s not hard to think of contemporary examples of each of these three strategies on the left. In some ways, we wanted first to recognize the virtues of much activity on the left, but also to recognize the present insufficiency of each of these three strategies (at least when taken up separately). So first, the mode of exodus covers various forms of prefigurative politics, which were widely experimented with during Occupy and various encampments. These projects exit the dominant society and live, in miniature, the change they want to see in the world. Of course activists involved in these projects have recognized, from the beginning, the limitations of such strategies, such as the difficulty and insufficiency of creating that separate society within this broader one. They’ve grasped the difficulty of generalizing from this smaller self-selecting community to the social whole. Then second, various types of antagonistic reformism have arisen through contemporary, very progressive electoral strategies, particularly in Spain, as with Barcelona’s and Madrid’s municipal governments, or Podemos on a national level. Or one could think of elements within Bernie Sanders’s campaign functioning this way, trying to work within the current power structure yet change it at the same time. Again, Toni and I consider this “within and against” strategy part of a noble and extremely important tradition, but of course we also recognize how often the long march through the institutions gets lost along the way. And then third, for the strategy of actively taking power, the progressive Latin America governments over say the last 10 years might fit in different ways: in Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Brazil. It is not hard to find limitations to this strategy too. Too often, even though the personnel have changed, the new rulers in power repeat the same problems of old.

So one could take this little catalogue I just made and get depressed and say: “Whatever we do, we’re doomed.” But Toni and I seek instead to think about ways in which these three strategies might get more productively interwoven with each other. One can think about possibilities for taking power while actually offering opportunities for an internal reformism, and for prefigurative practices to develop and spread.

Gilles Deleuze, for example, did a lovely video interview that proceeds according to the letters of the alphabet. For each letter the interviewer proposes a concept for him. When they get to “G,” the interviewer proposes gauche (left). Deleuze starts by saying there is no such thing as a government of the left. Instead, he says, there can be a government that gives space to the left. Here I think he means something like this notion of taking power, but taking it in a way that opens up substantial room for social and political alternatives, for a confluence of antagonistic and liberatory strategies. In some ways, this anticipates Toni and I interweaving these three steps or strategies — moving from the most local nature of prefigurative practices in the public square, towards a middle level of antagonistic reform efforts within the system, to the largest level of taking institutional power. Taking power does not produce any real victory until it opens space for the kinds of plural experiments and experiences that can push it further.

Now to situate ourselves more squarely in present-day circumstances, and still pursuing new types of experiments and experiences, could we pick up on Assembly’s (on your broader work’s) characteristic recommendation that, when searching for new possibilities for political cooperation, we first should look to social life and affirm existing capacities of the multitude? Here we might find, in the face of some seemingly insurmountable task, that we in fact already have developed the requisite capacities in exemplary fashion. So could we focus on the intensifying societal tensions you trace as “accumulated scientific knowledges allow us to think more powerfully…accumulated social knowledges allow us to act, cooperate, and produce at a higher level,” and yet such insight and wealth and power (collectively produced) still get so unevenly distributed? Part of what interests me here is that such formulations, once you have delivered them, seem self-evident, but I know it took decades of broader social developments and of hard reflective work on your part to arrive there. So would it make sense first perhaps to sketch the lived history (of first-person experience, of conversational engagement with oppositional communities, of theoretical sifting and sorting) by which you and Toni came to recognize the latent potential lurking amid the vast scales of time, effort, talent, work, leisure we at present already put into producing/reproducing subjectivities? Or for a more precise question or case to consider: since many technologies with which we now fuse our being can feel and can actually be so life-enhancing, even as (or maybe until) they become glaringly extractive, ultimately constrictive, how might more of us draw on these everyday engagements, practices, and reflections to gain a theoretical sense of what it means to live within our own moment’s historical contradiction?

The first part of what you say sounds pure Spinoza. I love Spinoza’s understanding of joy as really the central theme of philosophy, and joy as defined by an increase of our ability to think and act, which really amounts to an increase of being. And even one step further, Spinoza defines love as joy with the recognition of an external cause — that is, recognizing someone or something else causes you to think and act more powerfully. It’s not hard to recognize this in your own experiences. When you are with some people (even most people it sometimes seems!), you actually have less power to think. You thought you had clear ideas but then, talking with them, everything is suddenly muddled. But you also find that being with certain people and talking with them actually makes you think more powerfully. That, Spinoza tells us, is love. And that idea always lingers in the background for Toni and me.

Then as we move to the social and political level, we can continue from Spinoza to Marx, reflecting on how the development of science, of various material and immaterial technologies, can increase our social capacities. Marx emphasizes two aspects of this process. First, he argues that whereas scientific technologies and various types of machines are created socially, cooperatively, by a vast network of people, the value produced by them (as well as control over them) gets accumulated privately. Marx constantly works with this contradiction between social, cooperative production and private accumulation. So Toni and I follow Marx by calling for the reappropriation of those mechanisms, those systems of machines, that accumulated wealth. But as you point out well, we don’t just call for the reappropriation of wealth in an inert sense. We want to reappropriate dynamic forms of wealth, those again that increase our power to think and act. Toni and I don’t use the phrase “social joy,” but that’s what comes to me as you and I talk right now — something like what the French Revolutionaries proposed as a politics of “public happiness.” That helps to clarify why posing our project strictly in a political vein always will remain insufficient. In order really to think politically, one has to delve into the social, which, as we talk right now, seems to involve not only recognizing circuits of cooperation already functioning, but also recognizing how capital has extracted and appropriated their creations, and then how we can (or already do) reappropriate those capacities and creations.

Well under the sign of experiential joy, I wonder if we could tap one of its more SM veins — here perhaps by bringing in your preceding investigations of how power, even as it seeks to colonize subjectivities, might end up prompting previously untapped “constellations of resistance and refusals to submit to command.” Assembly detects a generative force not only in what immediately feels or gets culturally coded as joyous experience. So here, for example, you sketch a historically specific scene in which, “as our past collective intelligence is concretized in digital algorithms, intelligent machines become essential parts of our bodies and minds to compose machinic assemblage.” From there we reach a present-tense vantage in which “Labor has reached such a level of dignity and power that it can potentially refuse the form of valorization that is imposed on it and, thus, even under command, develop its own autonomy.” A 21st-century call to Marxist agency consolidates as “On this terrain opens a form of class struggle that we can properly call ‘biopolitical.’” So a few different questions pose themselves. First, again, how might you describe this biopolitical “struggle” playing out simultaneously within the individual and within society? What does it mean, and/or how does one, and/or how do we go about “struggling” for new social relations?

When thinking about contemporary forms of labor, which often quickly progresses towards thinking about new technologies, Toni and I find it helpful to emphasize the equally important realm of what we call affective labor, which basically describes how our emotions get put to work, how service workers at a restaurant, for example, have to smile at customers and act friendly. Or you might think, in a deeper way, of a hospice nurse building and managing social relations not only with the dying patient, but also with that patient’s family and friends. Of course a hospice nurse does all kinds of material tasks, like changing bandages and managing medications, but affective labor still stands out as this person’s primary work — as it might, say, with educators, or with any type of work that involves managing relationships to produce effects.

Many ways exist no doubt for workers to refuse this type of labor. Though often this means a more complex type of refusal than the model of an industrial worker walking off the assembly line — because affective laborers already produce these much more intimate forms of relations. And of course, most of these affective tasks remain highly gendered. So what we need to recognize is that affective labor already produces enormous capacities, and that people who provide this labor already have an enormous power. On the other hand, we need to recognize and respond to how this labor continually gets commanded and exploited, with forms of exploitation worse in many ways than the traditional forms of industrial exploitation. Having your abilities to befriend, to love, to care for people sold on the market seems even more of a violation. And that kind of recognition does tend, as you say, to reflections on biopolitical production, on the production not of commodities in the traditional sense — but instead the production of forms of life. That’s how we would define the “bio” part of the biopolitical, and how one might take biopolitical production as an entry point to thinking through what these capacities could do differently if deployed differently, and how one might resist or even revolt within that context, which remains a big challenge, and not always a clear one.

Toni and I don’t consider ourselves in a position to dictate precisely what a revolt in this domain should look like, but we can at least pose a question and make an analogy. If industrial workers who recognized their power (for instance that their managers or employers didn’t know how to make an automobile) could imagine a revolt by liberating their capacities to control the entire process, then we can ask: “How might affective laborers recognize and reappropriate their own equivalent powers? What might that analogy look like?”

And here Foucault and a variety of allied thinkers have helped us to recognize that production, even capitalist production, remains, at base, a production of subjectivity. Foucault helped us to see that we need to think of capitalism’s accumulation of commodities as only the midpoint of production, with capitalist control only secured through the reproduction of capitalist social relations — so through the production of subjectivity. To understand and attack capitalist social control, one has to recognize how we, as subjects, get created by, produce, and reproduce capitalist society. From these analytic recognitions, we can start to fathom the political grounds for rebellion and revolt and how to take control. That returns us to the crucial and primary (and obviously daunting) objective of any anti-capitalist struggle: how can we as present subjects take control of the mechanisms producing subjectivity?

So I didn’t want to start today by just asking: “What do you mean by ‘the entrepreneur’?” But as you discuss what it means to recognize ourselves as subjects both created by and now recreating capitalist subjectivities, and what it might mean to redirect this process towards a more liberatory mode of actualizing ourselves and others, does the multitudinous entrepreneur start to come in?

Absolutely. I hadn’t thought of it this way, especially since this proposal of an entrepreneurship of the multitude definitely has been the part of this book most hated by our friends [Laughter]. Toni and I realize perfectly well how this notion of the entrepreneur functions in contemporary neoliberal ideology: both through the adoration of Steve Jobs-type figures, and through the worship of start-up culture. In fact, especially in the university and in arts communities, when they say “entrepreneurship,” they mean: “We want to take away your funding. Go raise money yourself.” And of course many workers face even more precarious circumstances, with no guarantees of employment. When society tells these workers to become entrepreneurs of themselves, you see an especially cruel turn of neoliberal ideology — forcing people to celebrate, as their salvation, their own precariousness. We’re conscious of all that, and yet we want to redeploy the term.

In our books, Toni and I have tried to recuperate terms important for building political vocabularies of liberation, but which have become corrupted. “Democracy” functions that way, as does “freedom.” “Entrepreneurship” functions a little differently, since here we try to take a term first deployed by the right and make it mean something for us.

So what does entrepreneurship mean for us? First I’d go back to traditional formulations, say with the economist Joseph Schumpeter describing entrepreneurship as creating new combinations. Schumpeter primarily means things like putting workers together with a new labor process, with natural resources and other elements of production. But we can take that same notion of creating new combinations, or posing new forms of social cooperation — yet now to acquire and to design, as you say, enhanced capacities for the production of new subjectivities. Creating new forms of social cooperation can and does involve taking the reins of this processes of producing subjectivity.

Toni and I consider it entrepreneurial, for instance, that a group in Spain like the PAH (platform of those affected by mortgages) begins amid the 2008 economic crisis, when a lot of people start getting evicted. People can’t pay their mortgages, but what first begins as an anti-eviction campaign quickly transforms into a housing campaign. People occupy empty houses and provide homeless people with housing — all of which aids and contributes to the city of Barcelona’s electoral campaign. The current mayor, Ada Calau, was one of the founders and most visible figures in the PAH. I would characterize that overall process as an entrepreneurial endeavor, creating new kinds of social cooperation, and new subjectivities. Maybe any established political movement in fact creates new subjectivities through struggle in some sense. But we continually need to remember, with entrepreneurship, the notion of “enterprise” as a daring endeavor. Think of Odysseus as one of the great entrepreneurs. Toni and I, at one point, even considered calling this book Enterprise, and putting that Starfleet insignia with the upside-down “V” on the front cover. Luckily, my partner dissuaded us [Laughter].

Well as one mode of adventurous enterprise, taking (or retaking) the word means, as you say, getting out of oneself, foregoing the definitive framing of any party line, appealing to empowering heterogeneous communities who can translate one another, activate passions, actualize a shared grounding from which to step forward, taking reality as they go. I love these aspects of the book, of your broader work with Toni. Still (and as you also say), readers might want clarification on how this entrepreneur resists neoliberal models of the individual heroic capitalist siphoning off dynamic social/political potentialities towards more staid, instrumental, profitable ends. And along those lines, while reading your calls for a multitudinous entrepreneurship, one particular sentence at first stumped me: “entrepreneurship serves as the hinge between the forms of the multitude’s cooperation in social production and its assembly in political terms.” But here with that word “hinge” in mind, I’ll picture the economy providing some slot a worker (or workers) have to fill — though then this entrepreneur actively (inventively) elects to inhabit that slot, with all its machinic capacities, and, amid this process, to figure out and assemble the person (or collectivity) he/she/they want to become. So I know I use the term “pivot” too much, but here, with “hinge” in mind, could you further outline how this entrepreneur of the multitude declines to reappropriate fixed capital as personal property, instead directing any newfound capacities towards transforming the common, towards more fully actualizing the power of machinic subjectivity amid both social and political networks? How might this entrepreneur (individual or multitude) reclaim the power relations through which it first succumbed to affective seduction and constraint, though through which it also acquired the capacities to produce its own innovative, socially galvanizing subjectivities? How can this particular type of entrepreneur eschew the role of paranoid sovereign prude, the strategy-monopolizing leader, and play the part of promiscuous, desire-infused prosocial tactician? Or how, for one more streamlined image, might all of this fraught metaphorical fumbling with the entrepreneur take us to the more suave figure of the Prince — perhaps the most inassimilable figure for me still from Assembly? I did at least start to picture this Prince by contrasting it to the sovereign. The Prince seemed a little hotter, a little more sexy, a little more embodied, a little easier to befriend. The Prince might still have a mother after all (to add some female-coded figuration), whereas the sovereign simply descends from the patriarchal deity. I see Prince Hal maybe strutting about in Prince the performer’s royal purple. So, before this Prince metaphor strays too far, could you please call it back into Assembly [Laughter]?

That’s nice. The Prince does seem to provide one of this book’s crucial hinges. We’ve drawn in many ways on Machiavelli’s hinge between social cooperation and political proposition. Again we want to show that, in order to understand these contemporary political questions, you have to look beyond the political. You have to look towards social dynamics, but towards dynamics (like kinds of cooperation people experience at work or by living in a city) that don’t seem immediately political. So our entrepreneur and Prince figures seek to transform these various modes of social cooperation into a political project. Here maybe I should describe the Prince and the entrepreneur more as operations, rather than as figures. And the word “pivot” definitely fits, because we don’t want to frame social forms of cooperation solely as alternatives to politics.

So, for a contemporary example, the Oakland-based Black Land and Liberation Initiative stands out. This group and this project probably attract me because they announce themselves as liberating not only the land, but also other forms of social wealth. I learned about this on a webinar last summer, on Juneteenth, the date commemorating the end of slavery. And this project attracts me because of how it reappropriates land and social wealth not as some transfer of private property, but as a new recognition and reconfiguration of the common. What attracts me, in other words, is the social dynamic they’ve constructed, because that’s what illustrates this entrepreneurial function (or perhaps functions) of the Prince.

It would have helped to have talked to you a couple years ago, and to have factored Prince the performer’s strut, his hips, into our explanation of this Prince of the multitude. With the Prince figure, I in fact find it helpful to move in historical steps. Machiavelli talks about a specific person, a Medici who can fulfil this role. But already when we get to Antonio Gramsci in the 20th century, when Gramsci discusses the “new Prince,” he imagines the Communist Party as that new Prince. So a myth of unity functions through this Prince figure. But already through the party we’ve moved towards a collective project — certainly hierarchical, certainly with a central committee, but already we’ve shifted from what Machiavelli had imagined. And so Toni and I take this Prince metaphor one step further, with our Prince naming the ability of a democratic project to act politically. The Prince here emerges as the one who can act politically. In some ways it seems contradictory, but contradictory in a good way, to conceive of multitudes acting politically. Still it’s not that the Prince represents the multitude, but that the multitude learns to act like the Prince acts. How can a multitude of people be or become capable of strategy? How can they be capable of long-term planning, of the most important decision-making, and how can we carry this all out democratically, invitingly, persuasively, even charismatically? That’s the challenge.