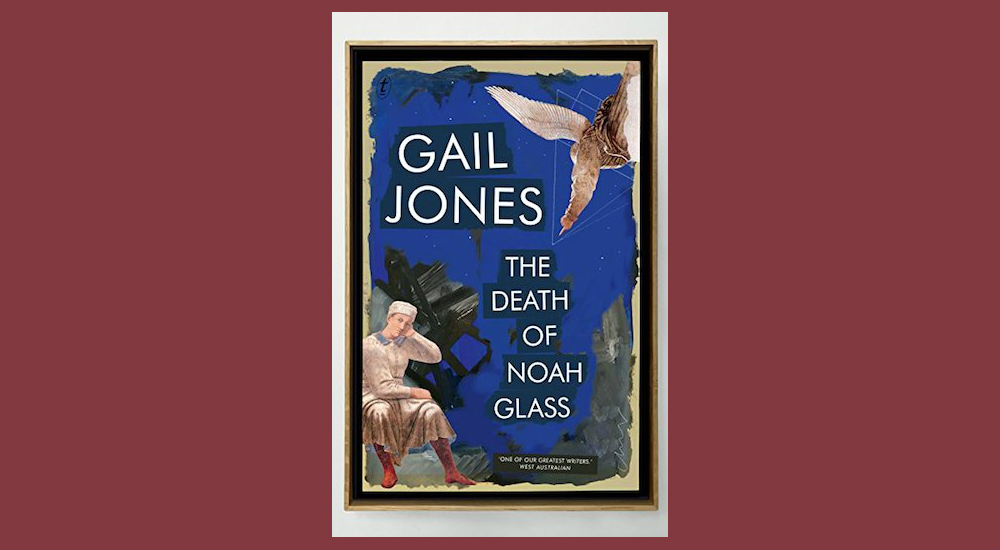

Gail Jones is an academic and novelist currently based in the Society and Writing Research Centre at Western Sydney University. She often depicts a world that stretches continents and references other cultural forms, from cinema, to music, to visual art. Jones has been the winner of the Colin Roderick Award and Nita Kibble Award, and was long-listed for the Orange, Man Booker, and Prix Femina Etranger. We caught up to speak about her new novel, The Death of Noah Glass, which was released by Text Publishing on April 2nd.

¤

ROBERT WOOD: Tell us about the narrative of your new novel The Death of Noah Glass.

GAIL JONES: The “narrative” is hard to summarize. My novels tend to be braided and multilayered in their form. At the center of this one is the mystery both of a man’s death and a Sicilian art theft; but these are the pretexts, as it were, for a more dispersed and unpredictable meditation on art, families, and the mystery of time. The central character, Noah, is an art historian, whose area of special interest is the quattrocento Italian, Piero della Francesca. Noah’s death is the subject of a police investigation, so I’m also riffing on and critiquing the detective genre, even as I’m playing with generic notions of suspense and guilt. Beneath all is the unfolding intuition that parents and their children are essentially unknowable to each other, and that this unknown is perhaps our deepest self. I’m interested in philosophies of time — so another aspect of the narrative is temporal distortions: folds and repetitions in time, stopped time, the “life-time” of any one consciousness.

If the book is about time, it is also about space. I immediately noticed how this new book moves around, and engages with the world of rooted locations and rootless cosmopolitans. That signals both a rupture and a continuation with other works. Can you speak to us about the role of nation, place-making, and your own experiences as someone who travels widely and lives in more than one place?

My novels often deal with transcultural experience and I’m interested in understanding cultural difference not as tourism or consumption but as a kind of radical encounter. There’s a renegotiation of self that happens abroad, when one is lost, or dislocated, or struggling in a language not one’s own. Travelers from the post-colonial nations of the South are perhaps more vulnerable to dislocation, sensing already their peripheral status and having sometimes internalized the belief that culture happens elsewhere. The Death of Noah Glass is set in both Australia and Italy and considers the seductions of the European art tradition. It also suggests, I think, that Australianness is sometimes a quality ascribed or inscribed by others — through novelty or ignorance or cultural condescension — so the nation (any nation, in fact) has a fictive and unstable aspect. I’m always struck by the romantic and simplified quality Australia has for some Europeans, when we know it to be no less complicated or contradictory than any other, with our own histories of violence, dispossession, and fraught nation-building. I’m convinced that our eccentric flora and fauna (the kangaroo!) are perhaps one of the reasons for the oddly endearing status of Australia.

If this is a world that moves times and locations, it is also one that moves media. The book is inter-textual with references to non-literary art forms, something you have long been interested in. Tell us about the role of “culture” in The Death of Noah Glass.

This is a novel preoccupied with visual culture, with frescos, paintings, cinema, posters, as well as with apparatuses of viewing, the camera, Skype, images seen through binoculars or microscopes. I’m interested in traditional art and iconography, the frames of understanding of the image, as well as secular and mass culture, especially cinema. I taught cinema at university for a while and have a deep interest in how stories are told in image sequences. The Death of Noah Glass takes seriously the idea that visual culture is so omnipresent as to be constitutive of our sensibilities, and that it also, in a sense, lends us fake identities and identifications. One of my characters is a blind man who is a movie buff: his interest is in imagining what he cannot see. My protagonist Noah has unusual theories on the work of Piero; his son is a contemporary artist interested in the Duchamp and the Italian futurists. So there are many and varied plays on art culture in my novel. At its centre, as a narrative engine, is the theme of art-theft.

I think, in that way, it is not only the highbrow that matters, and even in this frame of references the reader can see the elements of genre in The Death of Noah Glass from detective to murder mystery. And if not genre, then narrative devices that appeal to entertainment, flow, pleasure. How do you balance the world of ideas with the pressures of a good story?

I consider myself a novelist of ideas and have always thought that novels ought to be machines for thinking, as well as for feeling. Fictive cognition is a special kind of knowledge, and the inner life of reading engages us in a peculiar combination of sense recovery, memory, transference and simulated feeling. (Elaine Scarry’s Dreaming by the Book, a phenomenology of reading, is a text that makes sense to me in this connection.) Noah is found dead floating in a swimming pool: the model here was Sunset Boulevard in which the voice-over is posthumous and the dead man is the only one who knows the secrets of the tale. I’m fascinated by narrative suspense, but also by those moments in which we forget the forward movement of a novel and rest as readers in the stasis of a moment, or experience, or the pleasure of language itself. I try to combine all these elements in an intuitive fashion, not to plan too much in terms of where energy pools, one might say, or begins again to flow, and gently carry one onwards.

The book is also about relationships between people, not only between people and art; high and popular culture. What is the appeal of writing about parents and their children?

Children challenge adults in anarchic and creative ways. One of the delights of children is their capacity to relativize adult behavior, and to contest it by the daft lucidity of their questions. I think too that children remind adults of their own child-selves. So I’ve tried to center on a brother and a sister as adults, but both are dealing with the death of their father, Noah, and both are intercepted by recollections of themselves when children. I’ve also included a small child, a deaf girl, as a character: she too challenges her parents and demands they consider her strange forms of artistry and integrity. Children are fun to write and open prose to moments of extravagance. At the centre of Christian culture is the Holy Family: this is also under examination in my novel. Marx once noted the most interesting thing about Christianity was its adoration of a child; I think this is very suggestive, especially placed alongside contending adoration of a tortured man.

What is the hope of The Death of Noah Glass and writing novels in general?

I’m not quite sure how to answer this question. The writerly hope, I suppose, is that one’s novel matters in ways other than entertainment – that it might provoke serious thinking about the-meaning-of-life. This sounds a little grandiose, but I’m convinced that art (of all kinds) has a function of consolation (against meaninglessness) and revelation (against all that remains hidden). I hope simply that some fraction of this conviction might appeal or speak to others.