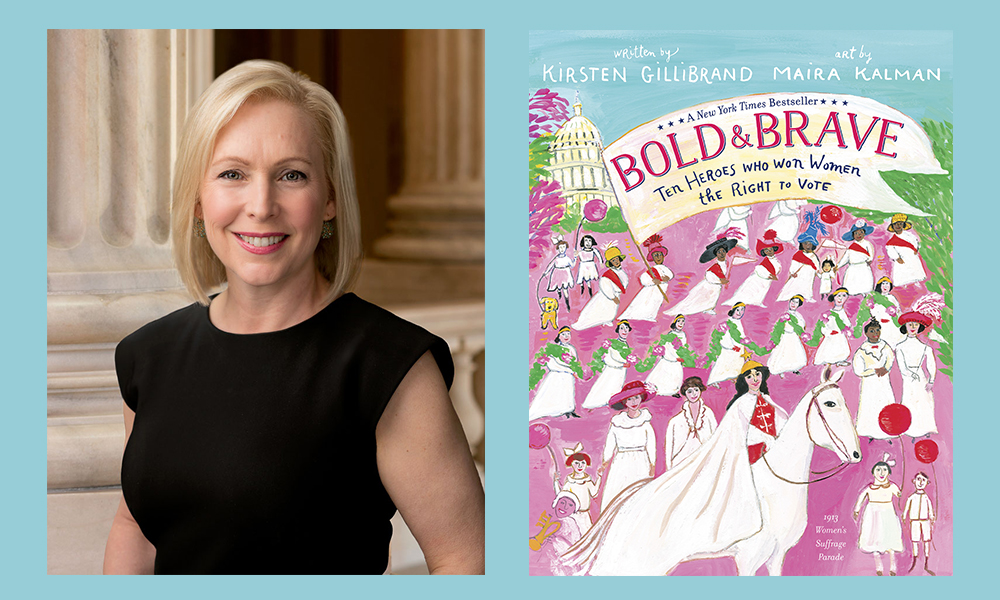

What can women disruptors of the past teach us about proper democratic functioning today? What makes a narrative of intergenerational struggle immobilizing or empowering, particularly for younger audiences? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Senator Kirsten Gillibrand. This present conversation focuses on Gillibrand’s YA book (with illustrations by Maira Kalman) Bold & Brave: Ten Heroes Who Won Women the Right to Vote. Since 2009, Gillibrand has served as a US Senator for the State of New York, with appointments on the Senate’s Agriculture, Armed Services, and Environment and Public Works Committees, as well as its Special Committee on Aging. From 2007 to 2009, Gillibrand served as the US House Representative for New York’s 20th district. Previously, she had worked as an attorney. She is also the author of Off the Sidelines: Raise Your Voice, Change the World.

LARB thanks Maira Kalman for providing illustrations throughout this piece.

¤

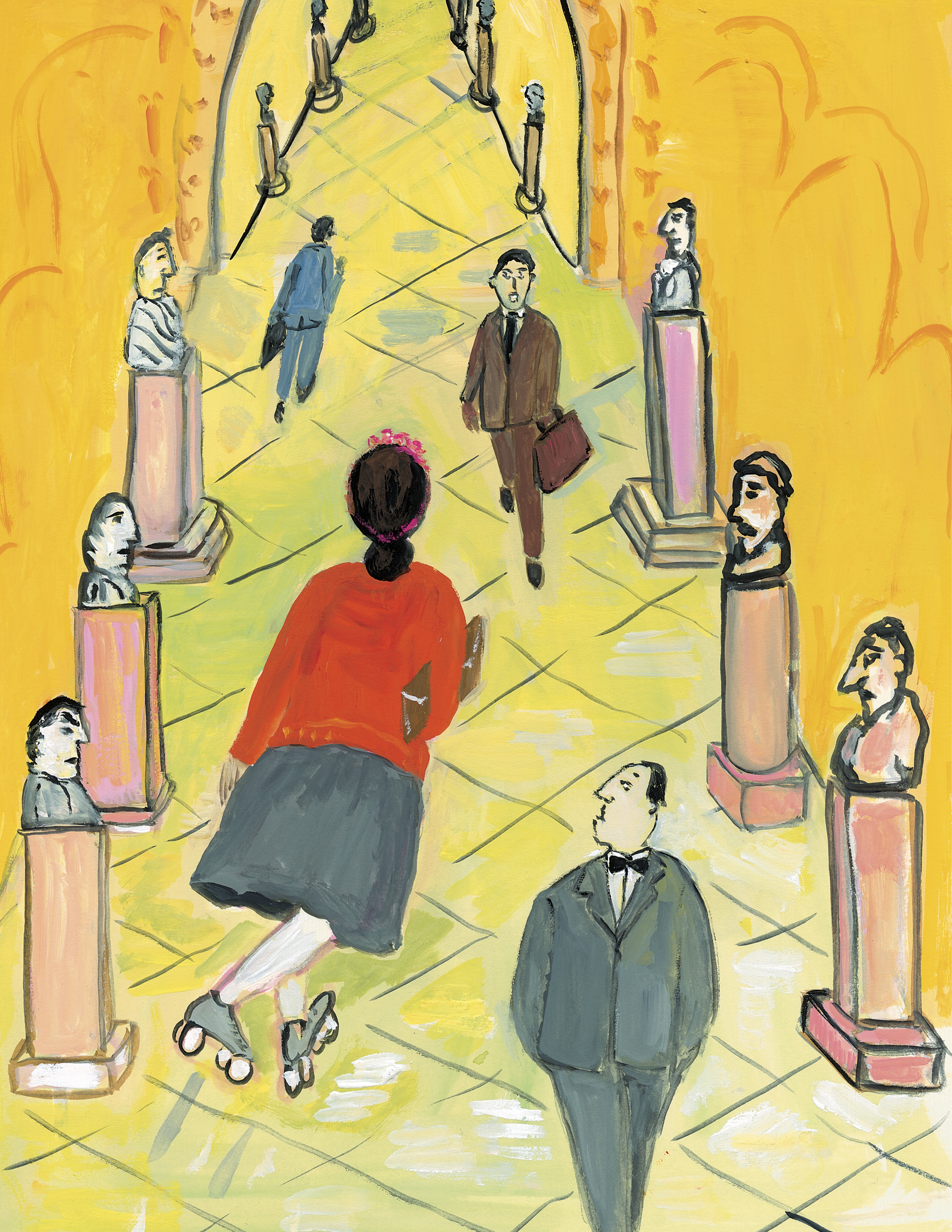

ANDY FITCH: First on a personal level, could you describe some ways in which your great-grandmother (recalling women’s World War Two-era workplace opportunities and national contributions), your grandmother (roller skating the halls of the New York State Capitol, where she herself worked), and your own mother (earning as a mom, for example, a black belt in karate) provided fundamental everyday lessons for how to “stand up, speak out, and fight for what we believe in”?

KIRSTEN GILLIBRAND: Well each of them showed me, in how they lived their lives, the importance of both standing up for themselves and also fighting for others. My great-grandmother contributed during World War Two as one of the Rosie the Riveters. I always admired that. My great-grandmother and her sister and my grandmother worked at the Watervliet Arsenal, and helped support the World War Two effort. My grandmother emerged as a trailblazer, getting involved in politics in an era when few women did. She organized, and got other women to care about politics, and helped a whole generation to understand why their vote really mattered, and that actively supporting candidates who shared their values mattered.

My mother (like her mother, and her mother’s mother) also dared to be different. She learned how to shoot a rifle, made the rifle team in college, went to law school, learned karate. She really thought outside the box and did things differently. Where I grew up, she was one of the few younger moms working outside the home. She became a professional role model not just for me, but for my friends. Five of my six best girlfriends became lawyers, largely because of my mother’s example.

Then in terms of historical role models, you describe this book’s central figures again as not just possessing great bravery themselves, but also teaching you to be brave, and informing your sense of obligation to teach others to be brave. Could you sketch any particular moments in life when that intergenerational inspiration, solidarity, responsibility among women leaders has really crystallized for you?

Becoming a mother definitely had that life-changing quality. I sensed this direct responsibility to teach my children to become strong leaders and help others, and show care for one another. That really helped me understand better how each generation has this obligation to lead the next generation, to provide an enduring vision of goodness and righteousness and compassion.

Every single woman mentioned in this book helped to build a better future for the next generation, and the generation after — through their bravery, their courage, their ambition to serve others. Every single one had, in some respect, a quite selfless streak. Each had the basic thought of: What legacy can I leave to improve people’s lives? So I felt the need to tell their stories. I’ve learned a lot from their examples, and I wanted to teach the next generation some of those lessons by writing this book.

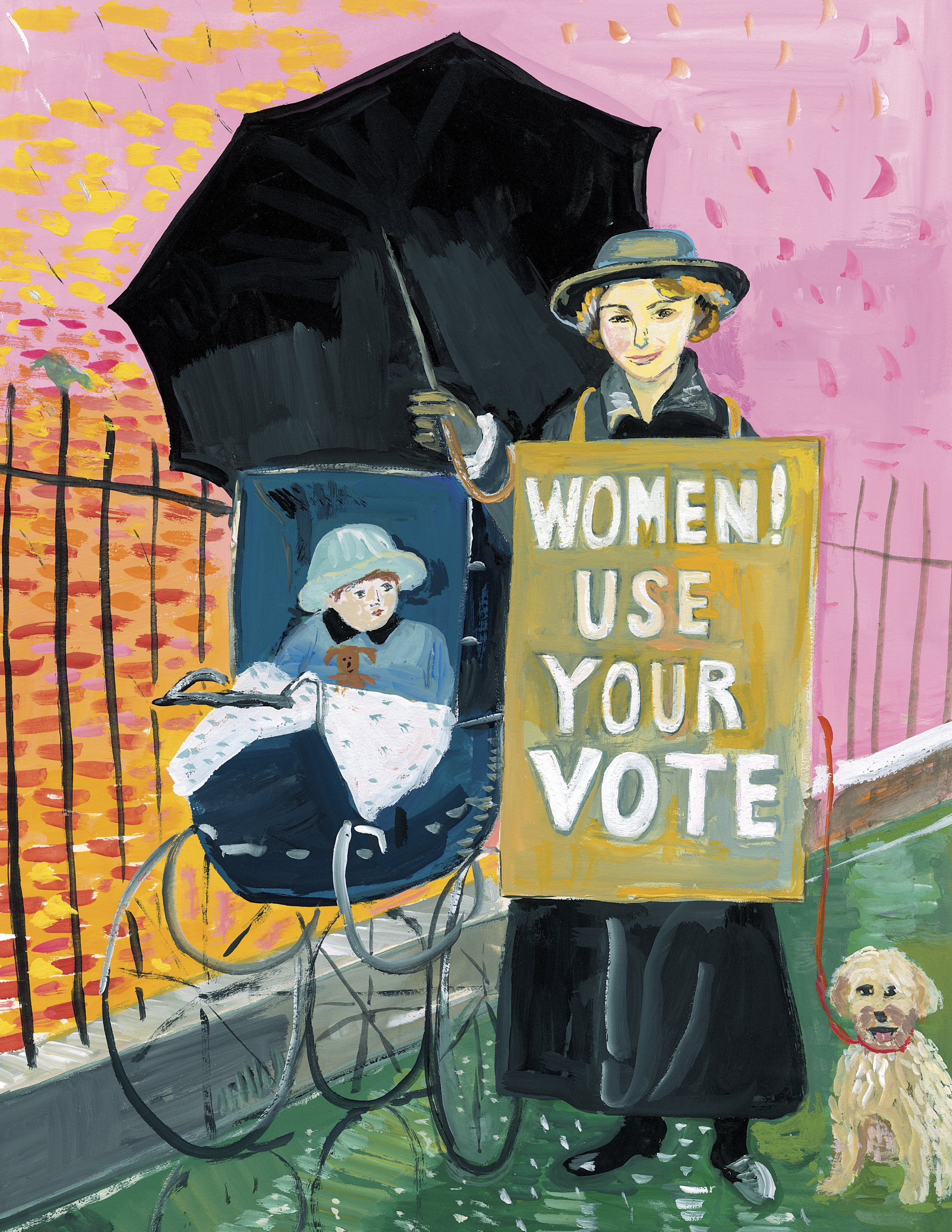

For one especially timely lesson from your book: at your grandmother Polly’s birth, she had no guaranteed right to vote when becoming an adult — nor, by extension, any secure place in our society’s democratic decision-making. For women of voting age in this especially charged 2020 election season, what most urgent case might you offer that failing to exercise this right means negating the hard-won efforts of preceding generations to secure an essential form of self-determination and civic dignity?

We face a generational decision right now, about which basic direction our country will take. President Trump, unfortunately, looks at civil rights and civil liberties for women, for people of color, for LGBTQ Americans, and wants to take us backwards. He doesn’t want to expand or enhance or secure our rights. He actually wants to restrict and reduce our rights, in a way no President ever has before. So for women and for mothers, I’d say that your rights and freedoms, and those of your children, and of your children’s children, face unprecedented threats.

Then alongside questions of civil rights and human rights, I’d broaden the focus to a constitutionally protected pursuit of happiness. President Trump’s policies have harmed our environment, for example, in disturbing ways. How can we just sit back and let clean air and clean water become more and more scarce? How can we watch climate change’s devastating impacts around the country or the world (with its wildfires and tornadoes and once-every-thousand-year storms), and respond by rolling back our environmental regulations? Given the grave threat that President Trump and the Republican Senate majority pose to our planet’s future, every woman’s vote today matters as much as it ever has.

And in terms of Mitch McConnell’s Senate majority, we’ve also of course had an all-out attack on many essential rights through the conservative judges they’ve confirmed. We’ve had an attack on our society’s basic wellbeing through Mitch McConnell’s shameless refusal (especially during this COVID-19 pandemic) to even let us vote on bills that could help so many Americans — even when these bills have bipartisan support.

So now returning to Bold & Brave (though still with today’s pressing public crises in mind), presumably you didn’t do a ton of research here, but how did putting together this book rekindle your sense of the “unimaginable challenges” faced by women predecessors?

Right, so I might get extremely frustrated with the misogyny and sexism I see in our everyday lives. But most women living in America today would find it hard to imagine lacking the fundamental rights to own property, to receive a public education, to face no overt and unapologetic gender restrictions when it comes to various jobs or opportunities. Women today of course deal with discrimination and sexism and misogyny all the time — but not to the level at which this inequality still gets enshrined by every single law. When you look back and acknowledge what the women in Bold & Brave accomplished, and particularly for the black women in this book, how much hate and discrimination preceding generations had to live through, you can see how far we’ve actually come.

Again that doesn’t mean we now should give up the work to dismantle institutional and systemic racism, or institutional sexism and misogyny. We all know that work’s not finished. But we should recognize that American women have fought hard to secure our basic rights. We’ve secured the legal capacity, when those rights get denied or threatened, to demand appropriate remedies through our court system. We have reached a different place. For me personally, as a US Senator, with this platform and this opportunity to highlight certain issues, and to lift up voices that rarely have been lifted up, I feel a deep sense of gratitude for all the sacrifices from those who came before — and also a deep responsibility to do whatever I can to advance these causes.

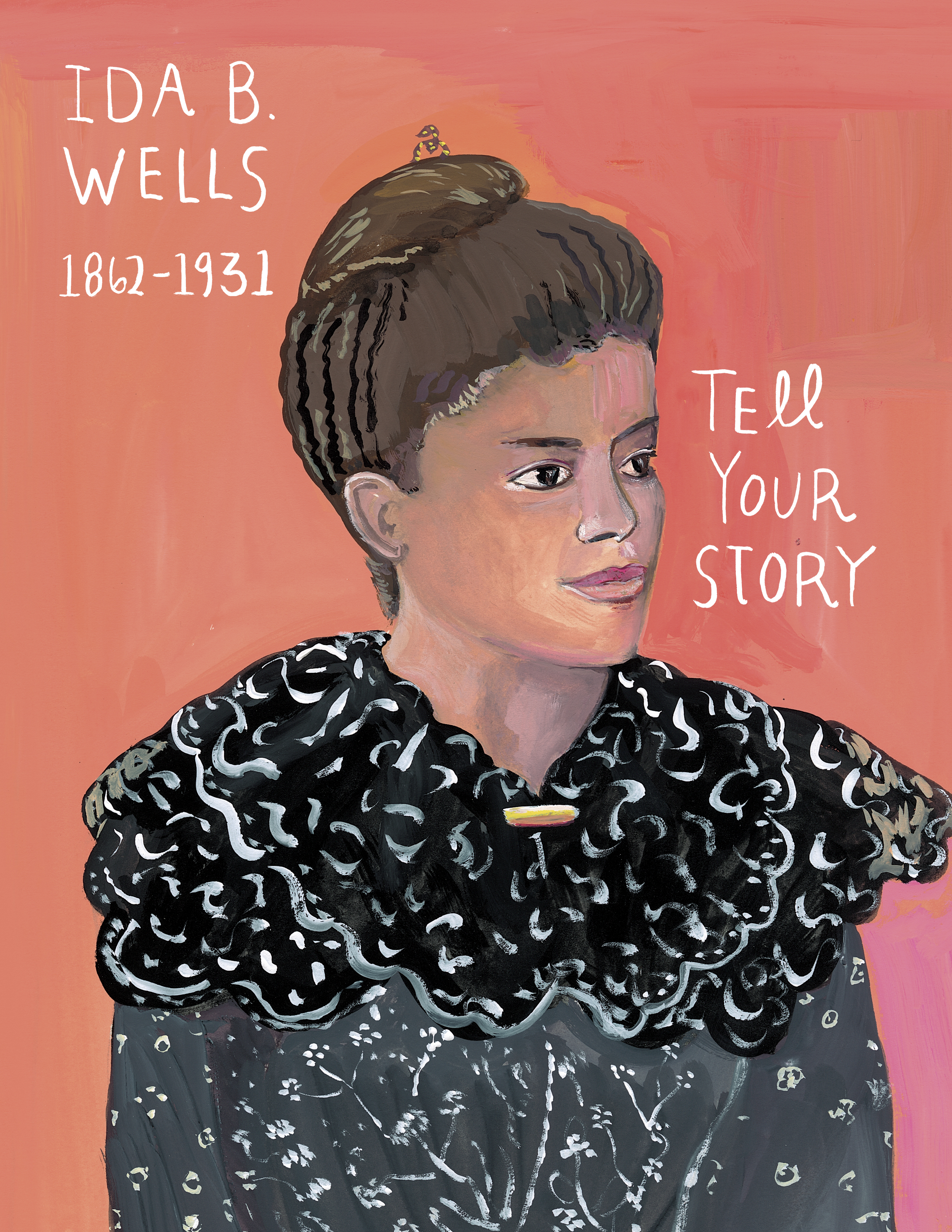

In terms then of connecting Bold & Brave’s particular audience to those historical predecessors, your book’s Ida B. Wells passage focuses on Wells’ journalistic crusades to right public wrongs, but doesn’t specifically address Wells’ most celebrated (today, at least) campaign, against lynching. Or Sojourner Truth and Mary Church Terrell get praised for raising intersectional concerns, but no reference appears to the sometimes problematic racial rhetoric of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. So as somebody who typically operates in the no-holds-barred realm of contemporary US politics, what sorts of guiding principles did you work with here for which topics and tensions to introduce to your YA readers, and which would require later stages of reflection?

You honed in pretty well on the major decision points, and on the basic question of which topics can a six- to nine-year-old fully grasp and absorb and gain knowledge from. I didn’t want young readers to undergo a potentially traumatic experience of having to imagine the horrors of lynching. America needs to face up to these horrors. But I couldn’t see how it would help young children to expose them in that way. I also decided not to discuss the forced feeding of enslaved or imprisoned American women. That just felt too violent and violative. I didn’t want girls to fear fighting for causes they believed in, because they worried about getting a tube stuck down their throat or through their nose.

For Elizabeth Cady Stanton, her racist rhetoric does point to a weakness in her character, and to an area of disappointment with our Founding Mothers. But I also wanted to praise her for all that she did right, and for her still quite inspiring example. For each of these women, really, I tried to emphasize their distinct contributions benefitting us all, and not to dwell on their mistakes. Each advanced the cause of suffrage in profound and unprecedented ways, and deserves to be recognized on those merits.

Somebody might ask, for example: “Harriet Tubman definitely deserves our praise, but did she really contribute to women’s suffrage?” The answer is: absolutely. Tubman skillfully used her renown as the Moses of her generation to focus on the fight for women’s vote, long after she fought to end slavery. She used her platform and her public stature to improve the lives of all women. So I wanted to present her as a historical figure who has few parallels when it comes to courage and generosity, especially on behalf of people enslaved — but also as a shrewd campaigner for the suffrage 30 years later, and as someone who never stopped helping others throughout her life.

Still on specific individuals, Inez Milholland stands out for magnificently providing the early-20th-century suffragist movement’s most public face — but with that role itself partially obscuring her manifold talents and ambitions. Your book strikes maybe its most melancholic note discussing Milholland’s abbreviated life. Could you say more about your sense of that lost potential?

I love Inez. But let me give an example of something you just touched on. During the development of a play written about this era, I went to a reading of the first act, then of the second act maybe six months later. And I couldn’t help asking the playwrights to think about changing how the portrayed Inez. They’d made her into this starlet who just loved all the attention. And I was like: “Are you kidding me? Are you really going to take her life and reduce her to that, just because in the first suffragist parade she wore a beautiful gown and rode on a horse and was so striking? Do you know anything about her? Did you read the biography?” I couldn’t hold back my anger, to be honest, at thinking of Inez in relation to this old sexist idea that: “She’s only famous because she’s pretty.”

I couldn’t believe these well-intentioned playwrights would still reduce this impressive historical predecessor to just her looks, in the same way some people used to try to reduce Gloria Steinem to her looks. Gloria Steinem provided an amazing role model as a woman using every aspect of her voice and presence and platform to revolutionize this country. Similarly, I see Inez as this powerful woman, this lawyer working for the Shirtwaist Factory reforms. Inez believed deeply in ending racism. I mean, Inez used her platform to push Alice Paul, which I consider pretty hard to do [Laughter]. So I wanted to capture Inez as a pivotal person often kind of left out of the history books, because she died so young. She never fully had the chance to make her mark. But I still feel grateful for her real and significant contributions.

Alice Paul, and Lucy Burns also, exemplify here a longstanding tradition of civil disobedience (as well as the perennial demonization of its “shocking” tactics — even when these just involve hoisting signs, or marching with banners). Could you talk about Paul and Burns informing a present-day activist sense of what it means to contribute to American democracy in this way?

I think of Alice and Lucy as partners in crime [Laughter], as just fearless fighters each bringing something different to the friendship. I picture Alice as the disruptor, as the one willing to go however far it would possibly take — as relentless, and massively self-sacrificing. She dedicated her whole life, her whole self, to this goal. And Lucy brought every talent she had, as perhaps the better writer, the better storyteller. Lucy had a lot to offer. But then together these two made each other even stronger and better.

Alice and Lucy also represented the next generation. The women leaders at that moment were mostly in their forties and fifties. Then here you have Alice and Lucy, in their twenties, drastically changing the strategy and approach to suffrage without asking their elders for permission.

Well I also appreciate your own concluding, onward-calling turn to the reader: “You are the suffragists of our time. What would you change if you could?” How might you hope to see future suffragists pursue this call in directions you can barely begin to glimpse?

So look at Greta Thunberg. Look at Emma Watson. Look at Emma González and the students from Parkland, Florida trying to end gun violence. Each of these young women already has broken fresh ground in her field, and in our culture. On climate, on women’s rights, on guns, you see these new national and world leaders not willing to take no for an answer. They might focus on global climate-change campaigns. They might organize in local communities to address something important in their home town. But in any case, these profound change-makers realize they can accomplish pretty much anything as long as they have the courage and the drive.

From what I can tell, Emma González and Greta Thunberg often couldn’t care less what women leaders in their thirties or forties or fifties are saying, doing, feeling. They’re just all in to change climate policies or gun policies, without much regard for who supposedly has the power or how to work through existing channels. I adore them both for showing us what the disruptors in this current generation look like. And for any young girl or boy who reads these stories in Bold & Brave about leaders from the past two centuries, I hope they’ll find themselves inspired to learn more about these figures, and about today’s young women leaders — and to become the leaders of tomorrow. We still have a lot to learn from the challenges and setbacks and breakthroughs for these Founding Mothers, and from how they did everything and sacrificed so much for the greater good.

Jacket art and interior illustrations copyright © 2018 by Maira Kalman. Published by Alfred A. Knopf Books for Young Readers, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.